Our Own Little Piece of the Earth

From the remarkable story of Stella Levi, an Italian Jew who lived under Mussolini

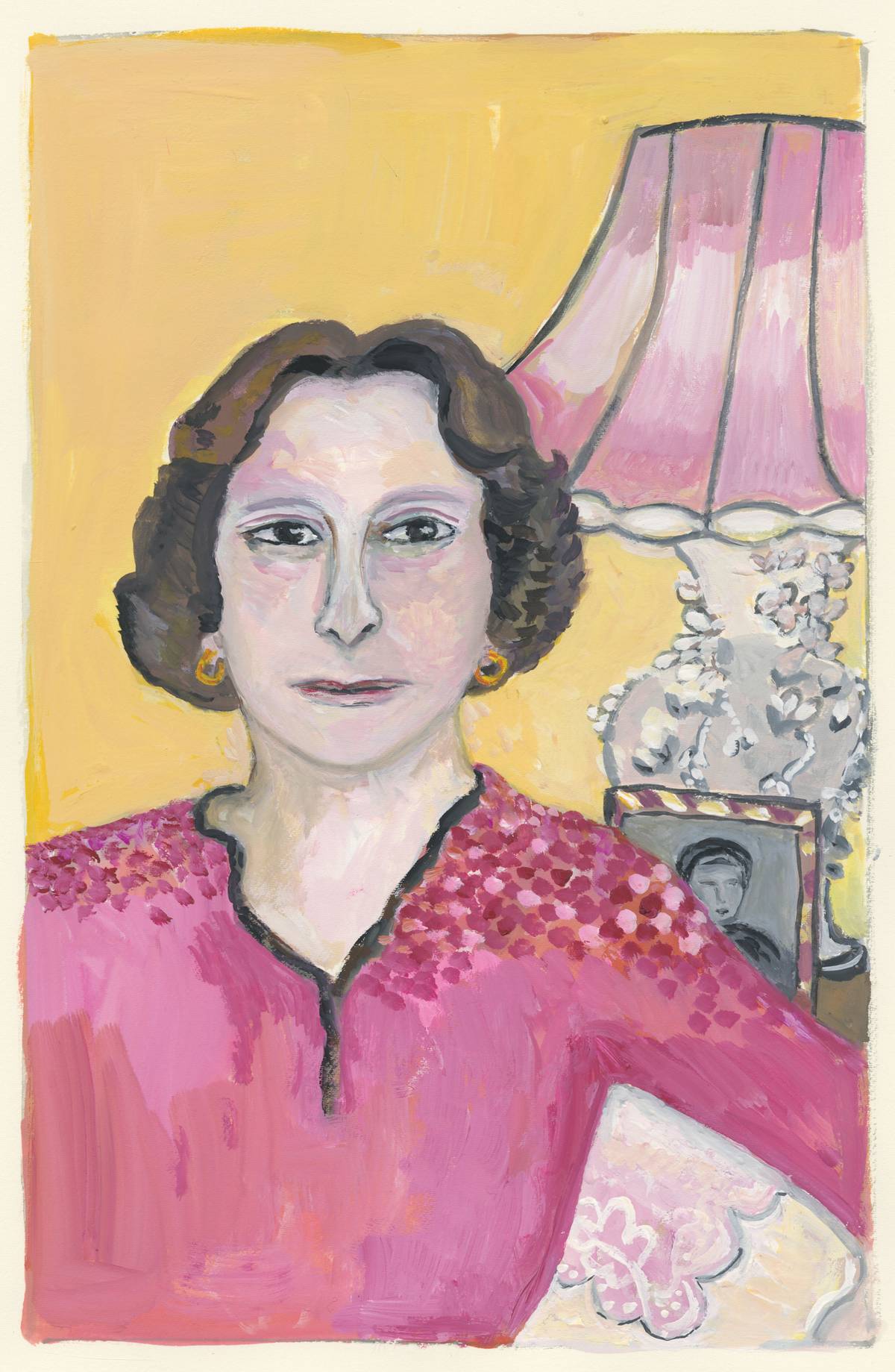

It was our own little piece of the earth.

Stella has said this to me before, more than once.

It was our own little piece of the earth—

Today she adds—

until they took it away from us.

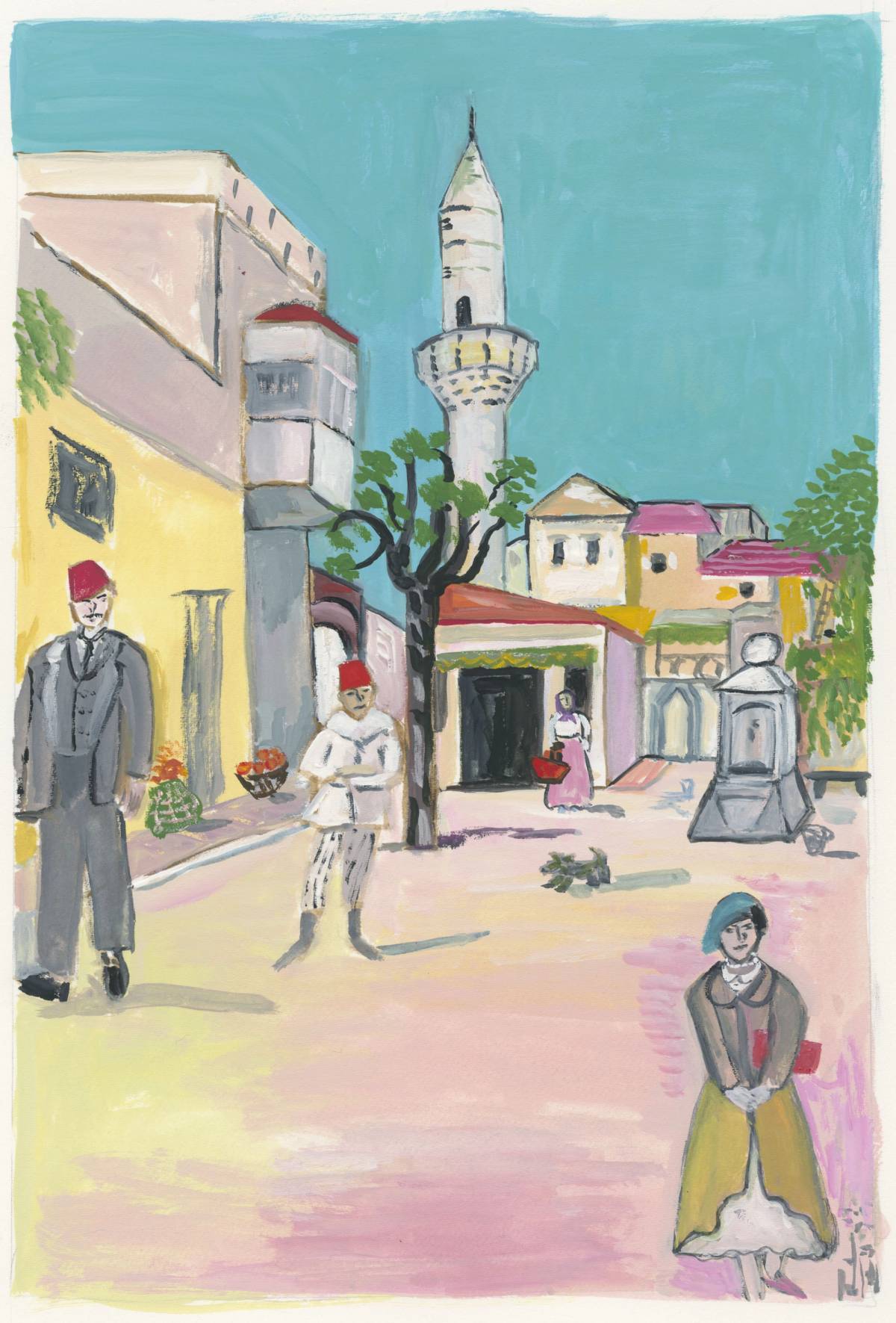

The first thing they took away from Stella along with all the other Jewish children on Rhodes was their right to go to school. To the young girl who was eager to do as well as her older sister Felicie, and who competed with her schoolmate Silvia Rozio for the gold medal, and who understood from an uncommonly early age what education meant, where it might lead, and who it might turn her into, this law hit her, as she phrases it, like a physical blow.

“In the fall of 1938 I was fifteen, and I was ready to begin prima liceo in the fall,” she tells me. “I’d been waiting for this day for years. I experienced this banishment as a loss of something very personal. I lost the right to be human. I don’t know if I can even talk about it.”

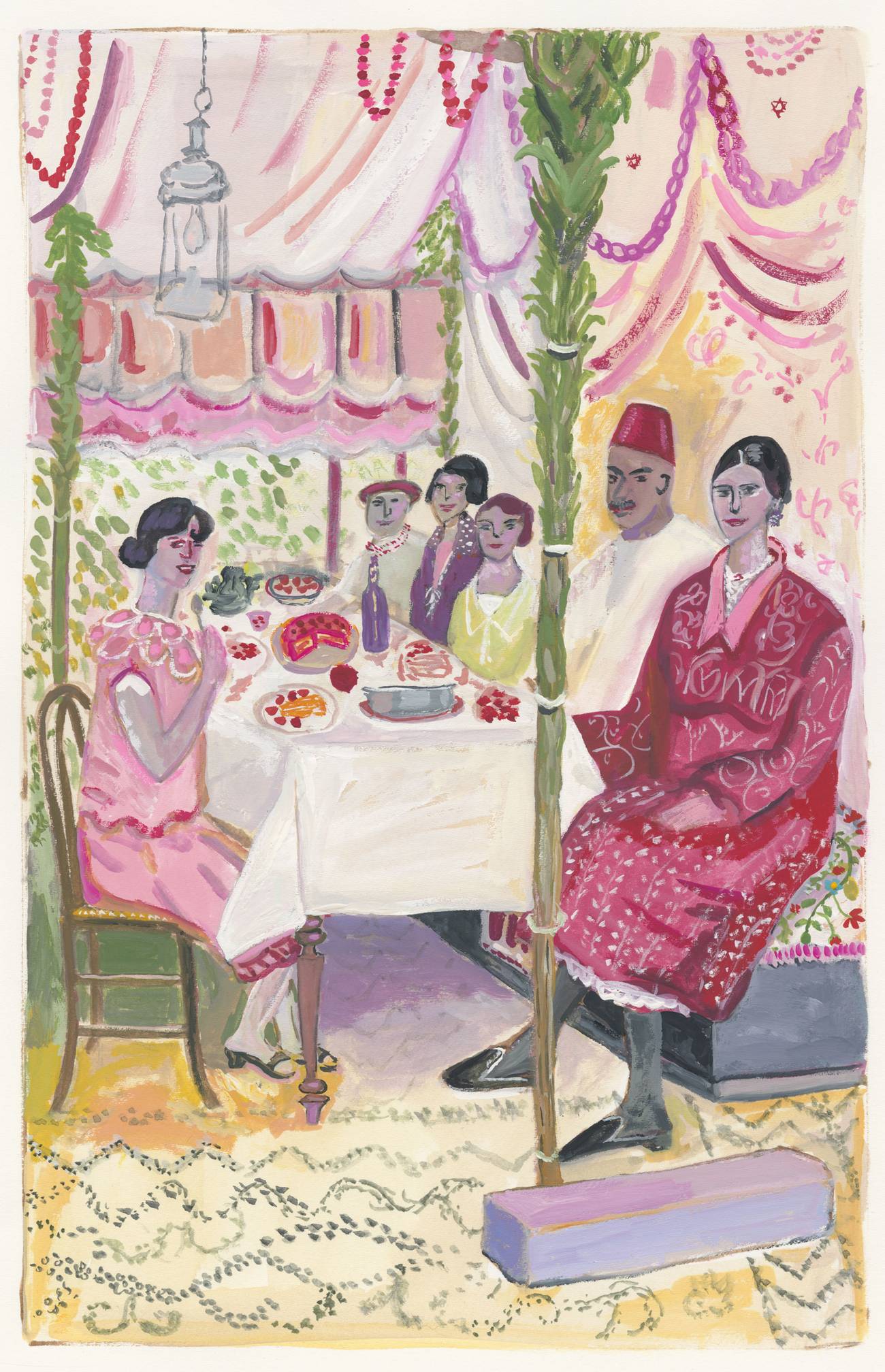

Stella doesn’t know if she can even talk about it, but once she begins, it’s difficult for her to stop. Felicie, she says, with all her reading, with her love of history, used to speak about their ancestors’ expulsion from Spain. It wasn’t as if they’d ever forgotten. The families in the Juderia spoke a different language, they had their own cuisine, their superstitions and cures, their proverbs and songs. They knew that, in the past, the distant past, they had been kicked out of their homes, their countries, their schools. “But now we lived in the modern world,” she says, her voice rising, accelerating. “We’d lived in Rhodes for five hundred years, for the past twenty-five years under these cultivated Italians who had brought us books, stylish clothes, who had imported opera, movies—Shirley Temple!”

Like her classmates, Stella was a good piccola Italiana, obediently dressing in a pleated skirt, white shirt, and a foulard around her neck in order to entertain the governor with the other schoolchildren at the stadium. They divided the students into formations that spelled out DUX and REX; Stella was part of REX. “I was proud to stand up at the top of the curve of the R. We paraded like all the Catholic children, we were little Fascist patriots, and then suddenly we were nothing. They turned us into nonentities.”

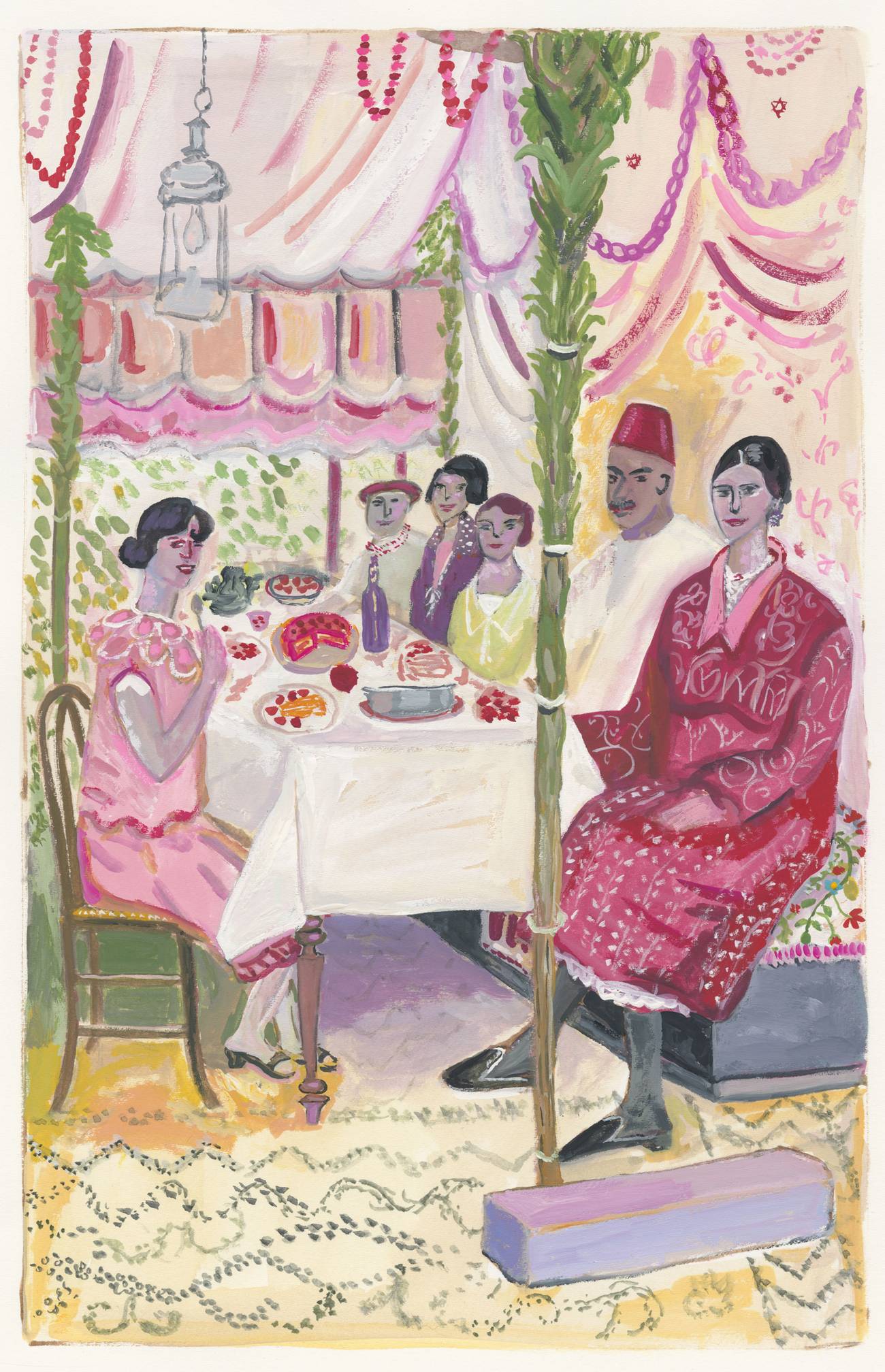

I listen as Stella tries to find a way to place this development in her young life. She describes her own sense of inferiority, something that haunted her for many decades afterward. She used to think it passed down to her from her mother, who felt in some ways lesser than her rich relations, or that it had something to do with being the last born of so many older, vibrant siblings. But then, she says, she sees herself marching across town to the suore, brimming with energy and curiosity and ambition; at home eavesdropping on her big sisters and perfecting her French by listening to them; at the beach listening to the boys talk, trying to understand what it was they talked about, and how they thought, and what they felt. “This is not the behavior of a person who feels inferior. Now I’ve come to see that it had to be what happened to me in 1938. The world around me changed—and, without choosing to, without wanting to, so did I.”

Sometime after this conversation, I attend a series of lectures by Michele Sarfatti, a leading scholar of the racial laws in Italy, and Stella, unsurprisingly, is there too, as always sitting upright, watchful and patient, but with a patience that is taut, catlike, and vigilant. Upstairs at Casa Italiana, in the same room where Stella and I first met, Sarfatti carefully lays out, over the course of three evenings, the results of a lifetime of study and research, of extracting data from old archives and files, of building, figure by figure, fact by fact, a portrait of what it meant to be a Jew in Italy, or in an Italian possession like Rhodes, under Mussolini.

As I take notes, I watch Stella out of the corner of my eye. I wonder how it feels, eighty-plus years later, for her to hear the experiences she lived through recapped impersonally, as part of the historical record like this.

Halfway through the third evening Sarfatti comes to 1938 and the years immediately following:

In the fall and winter of 1938, the racial laws were promulgated.

Only one public protest against the racial laws has surfaced, in a magazine published in Torino. In Napoli in September of 1938, street cleaners found little pieces of paper that said “stop racism.” That was it.

Jews were fired from all public employment, as soldiers, bus drivers, librarians.

Jewish actors and performers were expelled from concert halls, theaters, film companies. Their names were expunged from recordings.

Jewish lawyers, physicians, and midwives were expelled or limited as to their work.

Jews were barred from being street vendors, hotelkeepers, circus artists, stationers, vendors of Catholic sacred objects.

In 1938, A Night at the Opera—the Marx Brothers movie from 1935—was banned.

1938, all traces of Judaism were stripped from schools: teachers, students, Jewish authors, mentions of Jewish authors in reference books; Spinoza, for example, was no longer mentioned. Marx, Einstein, Freud were wiped from textbooks, publishers stopped printing new books by Jewish authors, and older books by authors like Henri Bergson were confiscated and withdrawn from the market.

At the mention of Henri Bergson, a favorite of Felicie’s, Stella’s back stiffens. From where I am sitting I cannot see her face.

On the following Saturday Stella reminds me that the racial laws weren’t just an installment in a history book, or part of a professor’s research, to her. Under the racial laws her father was constrained to sell his wood and coal business to a new—Italian—owner, effectively becoming the man’s employee. They did less and less business and took in less and less money. The family’s finances began to undergo an alarming downturn.

She pauses for a moment then goes on to tell me about the year she went, on the anniversary of the racial laws, to speak to a class of schoolchildren.

“Imagine if someone told you this morning that your father could no longer run his own business and then, this afternoon, that you could no longer go to school,” she said to them. “It would take you a lifetime to understand what that meant to your sense of who you are, what you deserve in life. I am what I am today because of what happened to me in 1938. I took it very personally. It felt like my family and I were being treated like animals—animals don’t need to work or study, do they?”

Six years later when she was sent to Auschwitz, Stella could at least see the enemy: “You knew what you were up against, you knew what you had to do to survive. You learned how to fight for your life. When I was kicked out of school, the enemy was not visible. Who was I to fight against? I had no idea.”

Excerpted from “One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World.” Michael Frank, © 2022. Reprinted courtesy of Avid Reader Press.

Michael Frank is also the author of a memoir, The Mighty Franks, and What Is Missing, a novel.