Israeli Historian Otto Dov Kulka Tells Auschwitz Story of a Czech Family That Never Existed

Why Holocaust accounts—and their fictions or omissions—can be a threat to the history of a complicated, tragic human reality

In 2013 the Israeli historian Otto Dov Kulka published a recollection of his childhood in concentration camps, Landscapes of the Metropolis of Death. Historians and general audiences praised the poetic and reflective tone of the book. Deported at 11 years of age from Theresienstadt, Kulka spent a year and half at Auschwitz and is one of the very few children of his age who survived. Quite unlike most other survivors’ accounts, Kulka’s book has little narrative: It is a collage of impressions, dreams, and metaphysical musings about the world of Auschwitz.

Yet this style masks the fundamental omission of a complicated family history, including adultery, bitter divorce, and a paternity suit. In short, what Kulka wrote was a book about a family that never was.

Beyond the poetic observations of death and mass killing, Landscapes tells a story of a Jewish boy, Otto, born in 1933, whose father, Erich, was deported as a political prisoner in 1939. Otto and his mother Elly are deported together with their relatives to Theresienstadt and then join his grandmother to be sent to Auschwitz in September 1943. In the Family Camp in Birkenau, they meet up with Erich, who conceives with Elly a second child. Elly and Otto survive the murder of the first transport in March 1944 due to being registered as sick. In July 1944, when the Family Camp is closed, they pass a selection and are separated; Elly is sent to Stutthof. In the emotional heart of the book, Elly parts with Otto, a modern Eurydice who walks away to save her unborn child. She gives birth to a boy, but her fellow prisoners kill the baby in order not to endanger their own lives. Elly dies in January 1945, during the evacuation of the camp, having contracted typhus. Erich and Otto survive.

The real story of Erich Kulka’s life, which I was able to reconstruct on the basis of the custody file, secret police files, survivor testimonies, and various other records, is more complicated and less poetic—and much more interesting and illuminating. For reasons I will explain below, Kulka writes his little sister Eva and his first father, Rudolf, out of his family history. We could speculate whether he wrote his family members out because their very existence would point out that the love story between his parents, Elly and Erich, happened in a way he wouldn’t like to acknowledge.

Perhaps unconsciously, Landscapes of Metropolis of Death is a search for a normal family, defined by a conventionally acceptable love between two parents. Yet Kulka’s omissions present a troubling gap. Nothing is left of Eva and Rudolf; they were murdered immediately upon arrival in Treblinka; they don’t have a grave. Like most victims of the Holocaust, they were not famous people remembered for their lives. This is why Holocaust survivors in their testimonies speak about their family members who perished: to remember them by their faces, characters, commemorating people of whom nothing—nothing at all—is left. In writing Rudolf and Eva out of his account, Otto Dov Kulka essentially wrote them out of history, and out of existence.

Eva Deutelbaumová was, at 11 years, the same age as the Berlin Jewish girl Marion Samuel, whose name was randomly selected as the name for a German prize for works that contribute to the fight against forgetting National Socialism. One of the recipients was Götz Aly, the eminent German historian of the German perpetrators. In 2003, he set out and researched the life of the girl Marion Samuel, found her photo, family, friends, addresses, her last days, and wrote a short, important book about her. It is in this context that the treatment that Kulka, the Israeli historian of Jewish history, gave to his sister appears ungenerous.

Kulka carefully framed his book as a non-memoir and a non-autobiography, “fragments of memory and imagination that have remained from the world of a wondering child,” based on 10 years of tape monologues. The associative, poetic, vague text of Kulka’s book has a double function: It allows him to erase the uncomfortable parts of his true family history while situating his book in the context of great literary Holocaust memoirs written by children survivors such as Ruth Klüger’s Still Alive, or Gerhard Durlacher’s Stripes in the Sky (both of whom were with Kulka in the Family Camp), which see the horrors of the Nazi extermination project from the a child’s fragmentary point of view. But Klüger and Durlacher—as well as Ida Fink, Primo Levi, Charlotte Delbo, Fred Wander, Liana Millu—were not only great writers; they based their writing on real-life events with which they struggled mightily to come to terms. Kulka’s poetic, meandering style enabled him to write a book about his childhood without telling uncomfortable truths, which he instead omits and actively erases.

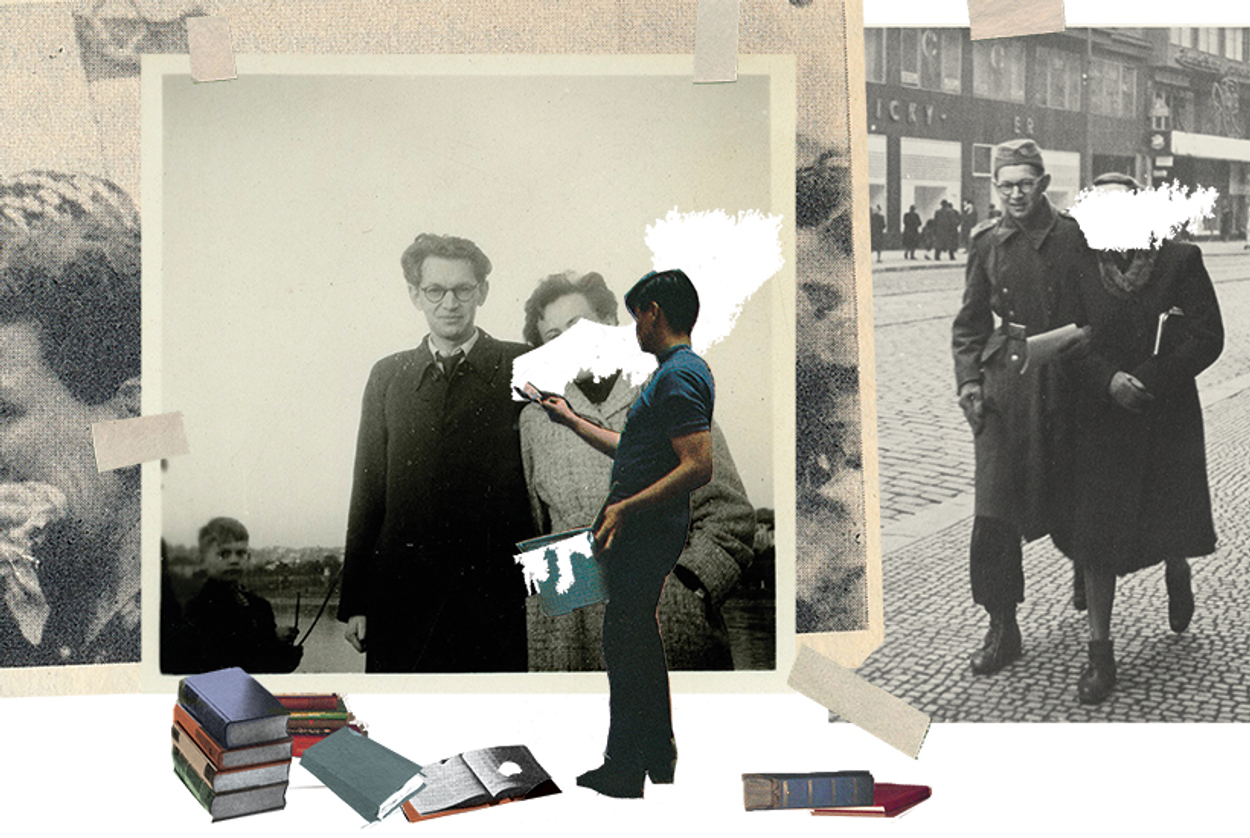

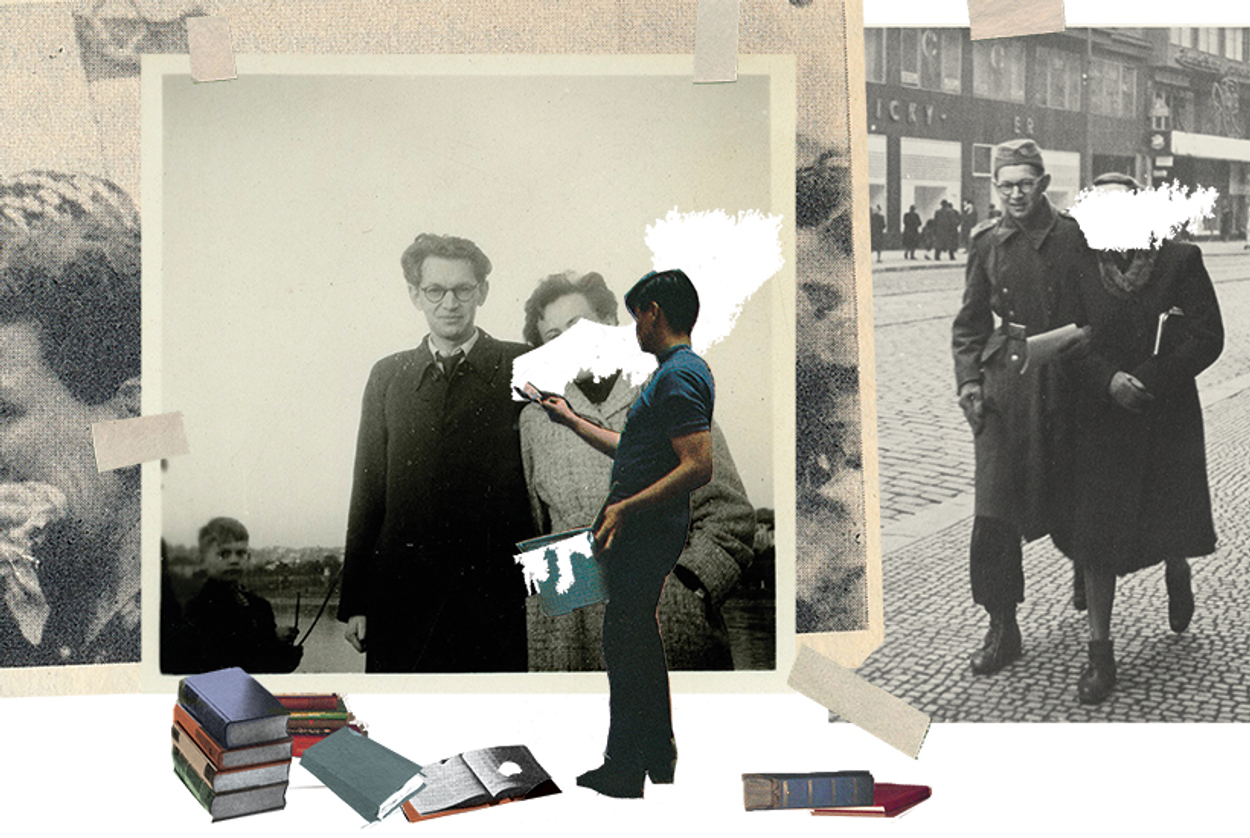

Kulka’s literary forgetting of his sister is also a part of another disturbing trend in the field of wartime memory. Scholars such as Bonnie Smith and Karen Hagemann have pointed out that men and women historians tend to write different kind of histories: Men often wrote official, and often conservative, histories of important men and their important decisions. Women historians included social and cultural interpretations and the lives of average people, resulting in histories written against the grain. A small but critical part of this trend is that when the 19th-century male historians wrote autobiographies, they often did not mention their women colleagues; they simply erased them and instead focused on their own, “more important,” lives. It seems fair to say that this practice has continued and now colors our historical memory of the Second World War. The autobiography The Memory of the Czech Left, written by my own grandfather—the resistance fighter, historian of the Third International, and dissident Miloš Hájek—is full of important men in his life: František Kriegel, Václav Havel, Jan Křen. But his first wife, my grandmother, Alena Hájková, who was with him in the resistance, an eminent historian herself—to this day the expert of the Czech Jews in the resistance—is mentioned only in passing. Don’t get me wrong: I love my grandfather. But we should think critically about this way of memoir writing, because it is a distortion of personal histories, which are inextricably and inexorably linked to distortions of the larger ones.

***

The beginning of Kulka’s story lies in the Vsetínsko region, a beautiful, mountainous area in the east of what is today Czech Republic, near the Slovak border. Vsetínsko had several Jewish families, three of which, Deutelbaum, Kulka, and Schön, were closely connected by marriage. In 1923, Elly Kulková, born in 1904, married Rudolf Deutelbaum, who was 15 years her senior. Rudolf was a wealthy man, running a steam wood mill in Halenkov that had belonged to Elly’s family. In 1931, their daughter Eva was born. Around this time, Rudolf took in his nephew Erich Schön, born in 1911, as a trainee. Perhaps it was during his traineeship, maybe even before, that Erich and Elly fell in love. In 1933, Elly gave birth to her second child, son Otto. The marriage between the Deutelbaums turned bad, while neighbors and relatives took notice of the affair. In 1938, Rudolf and Elly divorced.

After the divorce, Rudolf, who had remarried his much-younger close relative Ilona, sued for the custody of both children; one year later, he gained guardianship of Eva. Meanwhile, Erich sued to be recognized as Otto’s real father while Elly and Rudolf, who viewed Otto as his legitimate son, fought over the terms of Otto’s custody, even as the German occupation on Czechoslovakia started making its mark on the lives of the local Jews. Erich was arrested in June 1939; after his release, he and Elly married. In September 1940, Eva and Otto were banned from attending school.

Erich, who was soon rearrested together with his several other male relatives, including his brother-in-law Milan Kulka, was sent to Dachau, and then to the new, growing camp Neuengamme near Hamburg, where Milan died in 1941; his gentile widow Olga continued sending parcels to Erich, who was deported to Auschwitz in October 1942; from here, he smuggled Olga letters documenting the atrocities. In Halenkov, German authorities confiscated Rudolf Deutelbaum’s house, and he had to move into the house of his former mother-in-law; Elly and Otto lived on the lower floor.

But even now, the custody battle between the two parents carried on: Elly and Rudolf argued when the children could stay over with the respective parent, between the first and ground floor. In June 1942, Rudolf apologized to the court for not being able to attend the next custody hearing: As a Jew, he would need a special permit to travel. But moreover, he pointed out, the Jewish community in Valašské Meziříčí announced an upcoming “relocation” of all Jews. Children would be brought up separated from parents in children’s homes, so it would be no longer worth it to rearrange the status quo.

On Sept. 14, 1942, the Jews of Vsetínsko were deported to Ostrava and four days later to the Theresienstadt ghetto, which was then bursting at the seams with over 60,000 prisoners. The Nazis “solved” the problem of overpopulation and rampant diseases with a wave of transports to Maly Trostinetz and Treblinka. Three weeks after their arrival, Rudolf and Ilona Deutelbaum, with the 11-year-old Eva Deutelbaumová, were sent to Treblinka. Only two people among the 998 on the transport survived; the Deutelbaums were murdered immediately upon arrival.

One year later, in late August 1943, Hedvika Kulková was called up for transport. She had recently recovered from typhoid and was supposed to be protected, but the Jewish self-administration, struggling to fill the specifications given by the SS (5,000 Czech Jews) placed her name on the transport. Elly, Otto, and Elly’s sister Palma Michalovská and her son Boris followed the social code among the prisoners and joined Hedvika. Her other son, physician Marcel Kulka, along with his Austrian wife Martha and his mother-in-law, remained in Theresienstadt.

In Birkenau, the prisoners of the September transport didn’t undergo a selection and were kept in the special section, the Theresienstadt Family Camp. Erich, who worked as a locksmith in the technical detail and hence could move freely around the camp, had been looking out for all transports arriving from Theresienstadt and trying to help his relatives. On the day after their arrival he contacted his wife and Otto. He supplied them with extra food and brought Otto, when he was sick, to the infirmary, where he was registered as Otto Schön. Erich and Elly were able to be intimate, and in the winter of 1944 they conceived a child.

In March 1944, Erich saved Elly and Otto from the fate of their transport: Everyone from the September transports had been marked for death after six months. The SS had the remaining 3,792 people from the September arrivals (many had already succumbed to illness) separated and killed in the gas chambers on March 8, 1944. Several dozens of the Family Camp prisoners survived the selection: These included medical doctors and the prisoners in the infections barrack, as well as the twin children on whom Mengele was experimenting. Erich Schön brought Elly and Otto to the infirmary, knowing here they could survive the liquidations, in which Hedvika, Palma, and Boris died.

In July 1944, the Nazis closed the Family Camp; their plans of using the camp for a propaganda visit by the Red Cross had not been put to action, and they needed the manpower for forced labor. Young and old inmates, who before and after would not have passed the selection, now did; among them was 12-year-old Ruth Klüger and 11-year-old Otto Deutelbaum. Otto became one of about 40 teenagers from the Family Camp who, reunited decades later, call themselves The Birkenau Boys. Elly, whose pregnancy was not yet visible, passed to the women’s camp and several days later left for Stutthof.

Elly also had a new friend, Hana Roubíčková; the two had been introduced by Hana’s later husband and postwar secretary of the Prague Jewish community Kurt Wehle. Hana found out about Elly’s pregnancy in Stutthof, where the women were sent to work in the fields. As Elly grew larger, her friends bound her stomach with towels; but one day in September the Polish guard noticed. Elly was sent to the infirmary and gave birth to a girl, whose cries attracted the camp elder; the prisoner nurses then killed the girl with an injection. Elly recovered from the birth and later saved Hana’s life during the evacuation of Stutthof but died in late January from typhus.

***

In the emotional heart of Otto Dov Kulka’s book, Elly leaves Auschwitz for a forced labor camp, hoping to save her unborn child. But this poignant moment conceals a real earlier abandonment: Elly did not accompany her older daughter Eva on the transport; Eva left with her father, Elly’s ex-husband. The Jewish self-administration in Theresienstadt set up the transport lists, following the orders of the SS, until early October 1944. The self-administration honored the unity of families: Children under the age of 18 and their parents were deported together. If someone wanted to join a family member, they could; indeed, the prisoner society expected that children, if single, would join their parents.

Significantly, Elly did not volunteer to join her 11-year-old daughter. Her earlier choice to leave her child alone with a father was perhaps more defining: In Theresienstadt, Elly had a choice, whereas in July 1944 she did not, if she wanted to survive. The prisoners of the Family Camp knew that if they didn’t pass the selection they would be murdered. These choices do not make Elly a better or worse mother. Perhaps Elly and Rudolf even agreed that it would be more reasonable for Elly and Otto to stay in Theresienstadt. However, Elly’s choice to leave Auschwitz to save her third baby makes entirely different sense in the context of her decision two years earlier: She always chose to stay with the younger child, leaving the older one with the father.

On Jan. 23, 1945, Erich and Otto fled from an evacuation transport in Ostrava and hid with gentile friends from Vsetín; they were liberated in Zlín. Immediately after the liberation, Erich applied to be Otto’s legal guardian. Together with Ota Kraus, his fellow prisoner in Neuengamme and Auschwitz, they wrote The Death Factory, one of the first historical accounts of Auschwitz; the book is a classic. In 1946, Erich married Gabriela Kulková, the widow of Milan Kulka. Erich changed his (and Otto’s) surname to Kulka, to commemorate his first wife’s maiden name, which was also Gabriela’s and her children’s surname. Erich ensured that Otto inherited all of his father Rudolf’s property, including the steam mill. The assets were in Erich’s hands as Otto’s guardian; but most of them were expropriated—nationalized—by the Communist state in 1948. One year later, at 16, Otto Kulka emigrated to Israel.

In 1950, the remaining Kulkas moved to Prague. Erich, while working officially as technical clerk in the central storehouse, went on to become an eminent publicist and historian. He wrote about the Eichmann trial, contributed to the Czechoslovak mission to the Globke trial in East Berlin, bore testimony at the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, researched the famous escape of Vítězslav Lederer and Viktor Pestek from Auschwitz, and cooperated with Simon Wiesenthal (Erich’s sister-in-law Martha Kulka worked for Wiesenthal’s Linz office). One of the most active members of the Czechoslovak Association of Antifascist Fighters, the helpful, energetic little man was a bridge between the East and the West, the gentile political prisoners and Jewish survivors. The Czechoslovak Secret Police kept a mammoth file on him, baffled by his energy and goals, trying to make sense of why this man, whom they nicknamed Raven, was so interested in what they called the “persecution of Jews.”

After the Soviet occupation in 1968, the Kulkas emigrated to Israel following a three-month stint with Wiesenthal in Vienna. Now settled in Jerusalem, Erich continued his meticulous research. In the early 1980s, he fastidiously wrote out 60 Pages of Testimony, the memorial sheets of Yad Vashem for victims of the Holocaust. One by one, Kulka commemorated his siblings, nieces and nephews, cousins, aunts and uncles. He also wrote a page of testimony for his uncle and long-time rival, Rudolf Deutelbaum, and for Eva Deutelbaumová, Elly’s firstborn.

We do not know, and will never be able to find out, whether Otto’s (or Eva’s) biological father was Erich Schön or Rudolf Deutelbaum; judging from likeness would be unreliable, given that everyone was related. But really it is irrelevant: Rudolf saw Otto as his son and treated him as such until his death, when Otto was 9 years old. There is no way Otto forgot about his first father: He carried the surname Deutelbaum until 1946. Indeed, it was only with his emigration to Israel in 1949 that he started anew as a Kulka and, like many immigrants, adopted the more suitable Jewish first name Dov. Rudolf was indicated as his father in Otto’s witness testimony at the Auschwitz trial in 1962-63, and Otto alternated in his statements relating to Erich as his father, and as his stepfather, as he did when registered his place of residence with the police between 1945 and 1948, giving one time Rudolf, and another Erich as his father, erasing one name, replacing with another.

***

There is an angle from which Kulka’s distortions and omissions are simply part of the “famous man” genre of Holocaust memoir to which it belongs. One of the more famous examples of this genre is the testimony of Leo Baeck, the revered leader of Berlin Jewry and the honorary head of the Council of Elders in Theresienstadt, which has been received rather uncritically by scholars and often used as a primary text. When Hermann Simon found out in 2000 that Baeck made up a story about writing a manuscript for the German resistance that was actually ordered by the Gestapo, scholars and public alike were upset and incredulous. But in fact, Baeck’s entire testimony is a mix of facts and opportune stories. Deported to Theresienstadt in January 1943, the 70-year-old Baeck quickly became a prominent prisoner, which meant he was not subject of labor duty and received better food rations. Baeck also received two rooms, where he lived with his Berlin housekeeper, Dora Czapski. Baeck never mentioned Czapski. We know of her existence from other Jewish functionaries and of her signing in for Baeck for an invite to a meeting of the Council of Elders.

Are housekeepers so important in the larger order of things? They are central: Czapski made possible Baeck’s entire political and spiritual activity at Theresienstadt, where everyday activities in the ghetto kept people exhausted and severely limited in their spare time. In all my research about Theresienstadt I came across only one acting housekeeper, and that was Czapski.

Together with his housekeeper, Baeck erased other women from his family history. Describing the horrors of Theresienstadt, in particular for the elderly, he stated that three of his sisters died in Theresienstadt before his arrival and one briefly afterward. But this is not true. While two sisters did die in the summer of 1942, a third sister, Elisa Stern from Brno, died in March 30, 1944, 14 months after Baeck’s arrival—a long time by Theresienstadt standards. Anna Fischer, also from Brno, Baeck’s fourth sister, actually survived the war. Why would Baeck claim that his sisters all died when they didn’t? I don’t believe that someone would forget about the life or death of a sibling; Baeck probably wanted to focus his story on himself and his own suffering, even though his conditions in the ghetto were comparatively good.

Why did Otto Kulka erase his sister Eva, and why did he rewrite the child born in Stutthof from a girl to a boy? Kulka has given no hint of it in his work, or in his wider writing and speaking about the book. One possibility is that it is part of a wider trend in (not only) Holocaust memoirs, where the narrative mechanism has important gendered components, in which some of the male narrators remove significant but often private female characters (sisters, housekeepers, lovers) in order to ensure that the historical spotlight remains trained firmly and solely on them. It seems that the Holocaust engendered conditions in which women can be made to disappear from the historical record quite easily. Did Kulka fall victim to this syndrome?

No one remembers things the way they happened; human memory is like a muscle, shaping memories to be more logical, to endow us with more agency, toward what we wish had happened, incorporating books we have read and movies we have seen, and shaping the past in a way that makes is seem more unique. Ulrike Jureit examined this phenomenon on the example of Hans Wassermann, a Göttingen survivor of the Minsk ghetto who survived nearly four years in 13 camps and ghettos. During the postwar years, he came to believe that among the camps he was incarcerated in was also Treblinka, although he was never there—and in the period when he believed himself to have been there, the camp was closed. Yet Wassermann survived a truly horrible odyssey as one of a handful of German Jews; indeed, German Jewish survivors of Minsk are extremely rare. He added Treblinka probably because he read about it, and this camp too was an extreme place: As extraordinary as Wassermann’s story was, Treblinka fit in.

Erich (who died in 1995) and Otto Dov Kulka never wrote an autobiography, and Otto never gave an autobiographical oral history interview. In their statements for the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, they carefully and sparingly phrased their biographic information. From Erich’s 1988 interview at the Neuengamme Memorial we learn nothing about his wife Elly or son Otto, and even in his most candid, late interview for the Prague Jewish Museum, he carefully circumnavigated his prewar family circumstances. Remembering one’s murdered relatives can be traumatic; some survivors never spoke of their siblings or little children who were killed. But Dov Kulka did not forget his father and sister; and people really don’t forget their close family.

In addition, chance had it that a fellow Birkenau Boy who grew up in nearby Valašské Meziříčí, Michael Honey, became a hobby historian interested in the history of the Family Camp and Jews of the region. Honey liked to dig around, and looking around in the Vsetín archive, he found Otto Deutelbaum’s paternity case. He asked Kulka about it; Kulka replied that he didn’t want to talk about private family affairs. Honey told me the story one long evening at Sukkot 2008 in Kibbutz Na’an, when I was visiting Yaakov Tzur. Yaakov also worked on the Family Camp; he greatly enjoyed finding things, explanations, and plotting and arguing with, and against, colleagues.

Today, this generation of eyewitnesses who later became researchers is nearly all gone: Miroslav Kárný, the doyen of the Czech Holocaust research; Rudolf Vrba, the Slovak Jew who escaped Auschwitz in spring 1944 and spent the second part of his life working as an unafraid historian and witness; Misha Honey; and last spring, my friend Tzur. By the time Kulka published his book, all of these men, who loved to criticize and to pick fights, had died.

As long as it was Kulka’s private story, it was his to tell, or stay silent about. The problem arose when he published his book in its current form. As much as I understand Kulka’s wish to render in his memoir the family he might have wished that he had, the phenomenon of disposing of family members needs to be criticized. Werner Renz from the Fritz Bauer Institute, an expert of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, was the only expert to voice criticism of Kulka’s book; he pointed out the historical inaccuracies regarding the camp and its topography, which come as a surprise in a book written by a Holocaust historian, twice a witness at Auschwitz trials, who was also the son of a historian of the camp.

It seems to me that there is a misjudged bashfulness toward critical reading of memoirs of the Holocaust; perhaps a certain expectation that the Holocaust was such an extreme event, out of place and time, that the most odd, adventurous things did happen. Herman Rosenblat in his book Angel at the Fence added in his later wife Roma, throwing him apples over the camp fence at Schlieben. Like Kenneth Walzer of Michigan State University, the scholar who deconstructed Rosenblat’s autobiography, some historians have been championing a more critical approach. The Canadian Azrieli Foundation, which publishes memoirs of Holocaust survivors, has an academic expert check, and edit, every memoir; occasionally, they reject texts. While the slaughter of 6 million in the midst of civilized Europe was a singular and horrible event, physical laws did not stop working; to use Rosenblat’s metaphor, there were no angels handing out apples.

Otto Kulka’s family’s history is a complicated story. But then, many families had complex relationships, with affairs, lovers, and bitter divorces. In retrospect, perhaps it was the love affairs that made the victims human, and real. These stories about real people, though, are absent from Kulka’s Landscapes.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Anna Hájková is associate professor of history at the University of Warwick. Her book The Last Ghetto: An Everyday History of Theresienstadt is forthcoming in 2020 with Oxford University Press. She is working on a book on the queer history of the Holocaust and would be grateful for any information on relevant family archives. Her Twitter feed is @ankahajkova.

Anna Hájková is associate professor of history at the University of Warwick. Her book The Last Ghetto: An Everyday History of Theresienstadt is forthcoming in 2020 with Oxford University Press. She is working on a book on the queer history of the Holocaust and would be grateful for any information on relevant family archives. Her Twitter feed is @ankahajkova.