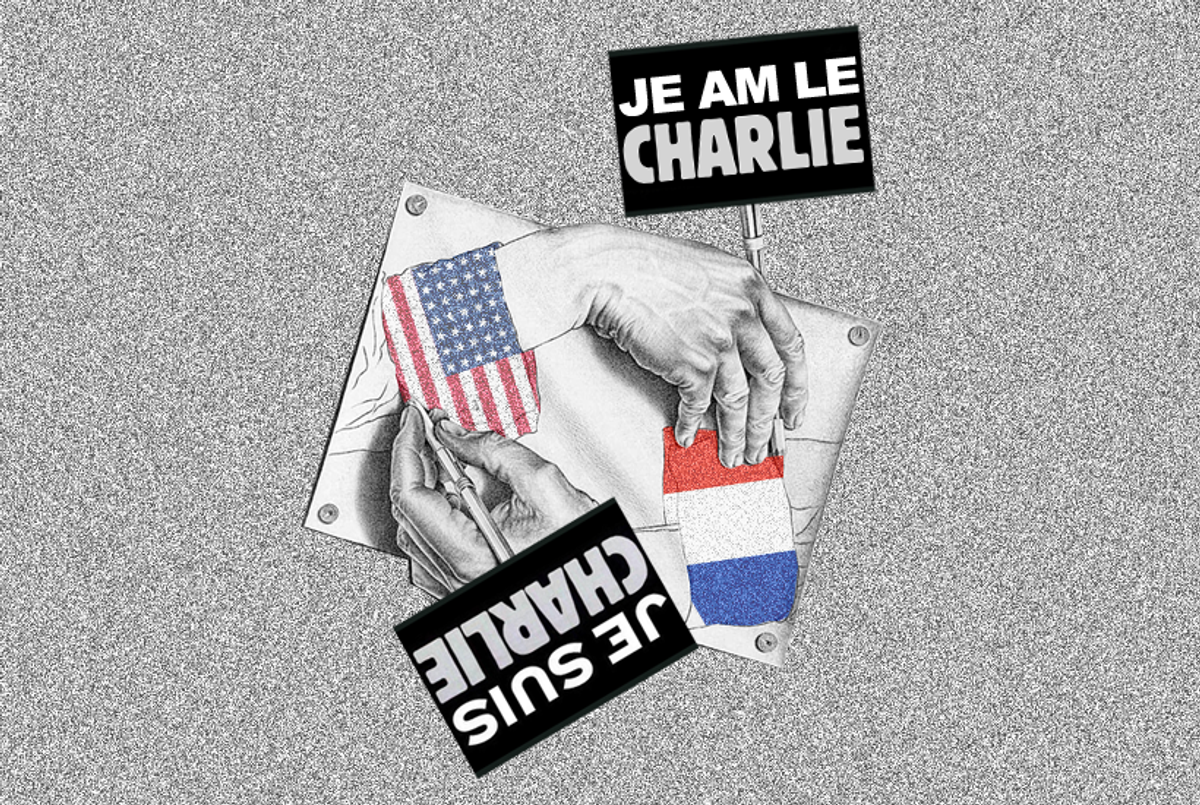

Observing the recent events surrounding the PEN Center award gala, which includes one for Charlie Hebdo, as an American writer living in Paris, one has the acute feeling of being a witness to the moral and intellectual self-immolation of the American intelligentsia. The fact that a petition protesting and boycotting the award was circulated back home and eventually garnered upwards of 200 signatories came as a shock. The energy devoted to manufacturing logical fallacies to justify denying the award to the heroic survivors of an editorial team liquidated by a terrorist death squad seemed almost impossible to fathom.

Upon closer inspection, the list of signatories turned out to be a mixed bag of the usual suspects—the avatars of coercive party-line uniformity along with the usual opportunists positioning themselves for greater glory. Still, one’s heart is liable to drop upon seeing the name of a friend or a figure one admired in one’s youth. For me personally, it was Eliot Weinberger’s intervention scorning the magazine as dealing in “frat-boy humour” and comparing it to a terrorist cell (perverse echoes of the puckishness that delights in his tales and travel essays) that made me feel sad. It took me a few more moments to realize that the feeling of primal dread arising from the depths of my subconscious at the sight of the list was linked to the vestiges of my Soviet childhood, when schismatic denunciations occasionally tore apart the Soviet writers union.

For about a day and a half after learning of the petition, I canvassed my American writer friends and acquaintances in Paris with the idea of organizing a counter-petition. The plan fizzled out in the face of widespread exasperation, disgust, and apathy as well as a modicum of careerist self protection. Why make an enemy of Nicole Aragi, the powerful “quality lit” agent whose name also appeared on the list, along with the names of some of her clients. Still, in the cafés, the bars, and especially over the social networks, expat American scribes and literati commiserated with one another over the peculiar odor of American provincialism intermixed with haughty exceptionalism that had wafted over the ocean. The news from New York was obnoxiously parochial, humorless and puerile—more on that word in a moment—and completely devoid of any contextual understanding of French tradition or satire. For that I would direct the interested reader to the work of the philosopher Justin E.H Smith, the American in Paris who has thought the most deeply, cogently and sympathetically about Charlie Hebdo.

Those of us who have been living abroad (especially those of us who held progressive values) for a long time are still struggling to comprehend how the ideological fault lines have moved in our absence. Several people that I spoke with in the days immediately after the letter’s publication experienced it as a double betrayal. Morally, this felt like a form of deluded complicity with the murderers who had effectively institutionalized (de facto) martial law in the streets of Paris. (As I write this, French army troops stand sentinel at the synagogue on my street, literally outside of my door, with FAMAS-f1 assault rifles.) On the intellectual level too there was treachery. The equation of the award with specious support for an “imperialist war on terrorism” and “state enforced secularism” seemed simply bizarre, the implication or subtext being that the spate of violence through whose wide-ranging aftershocks we are still stumbling was simply a minor inconvenience for far-away people, and therefore could easily be trumped by programmatic blather.

There was also a sense of widespread amazement that more due diligence had not been applied to interrogating the fundamentals. (“Their account of Charlie Hebdo is like a Google-translated version of Rabelais,” the American writer Lauren Elkin lamented.) It seemed absurd that the French were now being lectured on the subject of post-colonist racism in an almost farcically condescending manner by self-appointed American arbiters who did not speak the French language or understand French culture. The particular history of French anti-Clericism as well as the internecine debates surrounding Laïcité did not appear to interest them. The categories of racism, Islamaphobia, and blasphemy were thoroughly enmeshed, as the binary lens of “white” and “other” trumped all other possible conceptual readings of the situation. Stale prudishness was mistaken for solidarity with the oppressed. On the other hand, the most obvious and valid criticisms of the French republican model—such as the fact that rigid adhesion to Laïcité is counterproductive to the objective of integrating minorities—were made by no one.

Instead, what we heard repeated again and again was pure fiction predicated on purely American concerns, like the accusation that the staff of Charlie Hebdo were “obsessed with Islam.” That argument would in any case soon be thoroughly debunked by Le Monde’s recourse to statistics. Charlie Hebdo’s only English-speaking columnist, the Irishman Robert McLiam Wilson, wrote an entire article in the New Statesman decrying the moral ludicrousness of it all.

All this is not even to broach the ancillary matter of the understandably flabbergasted reaction of the French. French journalist Anne-Elisabeth Moutet, who was educated in England and often explicates French politics in the British press or television, told me that she was livid at what she identified as the patronizing and willful ignorance of sectors of the American intellectual class. “We in France think U.S. political cartoons are lamentably literal and hopelessly petit-bourgeois, with no irony or finesse,” she informed me rather grandly. “Charlie was certainly on its last legs, but for decades it was a huge success, and I don’t know many French people who didn’t buy it at one stage. Everyone here has seen it and knows its cartoonists, some of whom also worked for mainstream papers. Cabu and Wolinski, in particular, who started their career in the 1960s and worked everywhere from Pilote (of Asterix fame) to Le Canard Enchaîné—the grand ancestor of the political and satirical weeklies, and Paris Match. Cabu’s graphic reporting of the fall of the USSR was of Goya-like quality. This is something that brings together the French right and the French left. They were like family to us.”

The pesky questions of what Charlie Hebdo actually was and what the natives might think about it aside, the most subtly noxious issue one confronted in these debates was the older strain of American prurience lurking in the rhetoric of the magazine’s American defenders. Even some of the more lucid champions of Charlie Hebdo in the Anglosphere, who have lived in France, read French, and understand the historical context perfectly well, felt the overriding need to preemptively cover their commitments with self-exculpation for having even looked at a copy of the magazine, many, many years ago. Such apologias for Charlie Hebdo generally commence with an emphatic underlining that the magazine was a puerile taste which the writers, such as Adam Gopnik, do not fully share.

This is if one stops to think about it for any length of time repugnant in its own way, a ritual of bourgeois ideological self-abnegation, lacking all esprit and vitality, which again reminded me of my Soviet youth. The purest and most egregious distillation of this prim frostiness can be found in novelist and blogger Caleb Crain’s otherwise nuanced and intelligent appraisal of the debate and the cartoons:

They aren’t funny. I think there are two reasons. First, they’re puerile—pitched at roughly a Mad Magazine level of sophistication—and in the American ecosystem, editorial cartoons are usually a little more tony, and don’t seem to have as broad a permission to engage with racial imagery as movies and comics do. Taste is to a great extent learned, and I’m afraid that an American reader of my ilk just isn’t likely to find vulgar and puerile cartoons about politics much to his taste.

Reading this, the only thing one can do is proffer one’s professional empathy: It can’t be easy writing in the contorted posture of pinching your nose shut with one hand while typing with the other.

Still, Crain’s intuition that a magazine of such salacious ribaldry and iconoclasm would never have been able to survive (let alone garner critical importance) for any length of time in an American context is entirely accurate. The act of transmuting purely political judgments into those predicated on individual taste can only ever be a politically censorious move. Yet such right thinking citizens of the American republic of letters have evidently never experienced the sheer pleasure of walking up to a Parisian Newspaper kiosk and purchasing the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo with 3 Euros in change. So while it should be absolutely unnecessary, and perhaps should not be done, I would like to offer a defense of the magazine, predicated purely on aesthetic grounds.

Charlie Hebdo is, let it be said, utterly joyous and carnal fun for anyone with an anarchic sense of mirth. It is vital and scabrous and it skewers all religious and political pieties with equal glee. Descended from the glorious genealogical tradition of Honoré Daumier and the bande dessinée, the planar blocky design is all thickened line and sensuousness. The covers are strikingly designed in a creamy pastel palette. It is true that the cartoons do range all along the spectrum in quality, but many of them are uproarious, witty, and shrewd. They characterize the convention of sublime take-no-prisoners political savagery and sexual bawdiness that has always run through French political tradition, and which simply does not exist in American politics. Many of Charlie’s targets richly deserve the mocking opprobrium. The entire project is permeated with sex and libidinous fidelity to the bodily appetites. It is earthy rather than “vulgar.”

The sloppy displacement of America’s own racial problems, both historical and in recent guise, onto the French context does America and American writers no favors. From a distance, the PEN boycotters appear to have confused the politics of liberation with the politics of literary status. Intersectionality, indeed.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Vladislav Davidzon, the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review, is a Russian-American writer, translator, and critic. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.