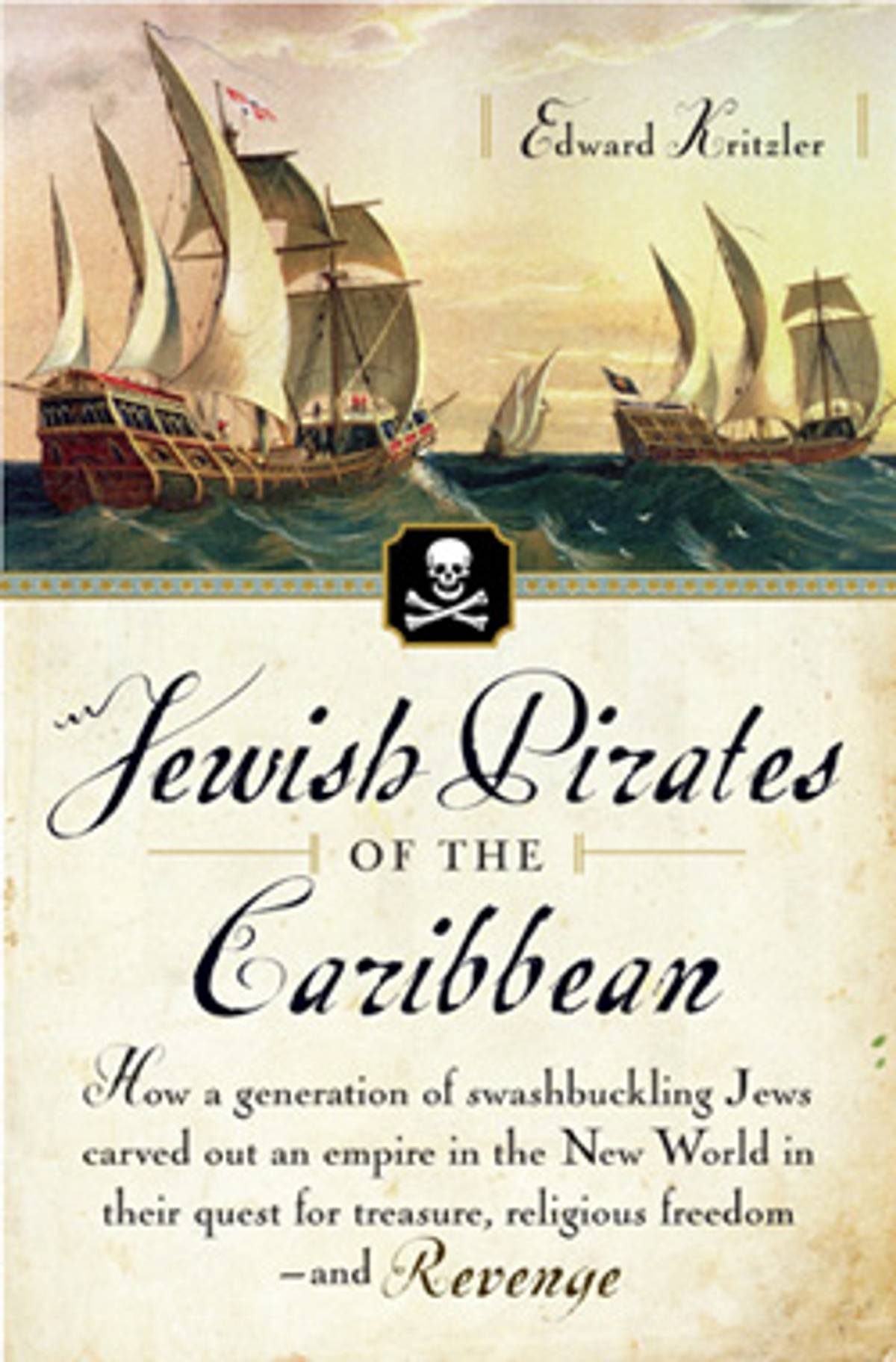

There are places you expect to find Jews and places you don’t, and in the second category, the deck of a pirate ship ranks pretty close to the top. The very title of Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean sounds like the premise of a science-fiction novel—maybe a sequel to Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, in which Yiddish-speaking Jews colonize Alaska—or else the punchline to a joke. But Edward Kritzler’s new book, despite its serious flaws of scholarship and interpretation, has the merit of reminding us that, in fact, Jews and the descendants of Jews played a significant role in the European colonization of the New World—as merchants, diplomats, spies, and yes, even pirates.

The reason has to do with simple chronology: 1492, known to all Americans as the year Columbus sailed the ocean blue, is remembered by Jews in a very different spirit, as the year Ferdinand and Isabella banished the Jews from Spain. In the ensuing diaspora, many Spanish and Portuguese Jews, including the conversos who continued to practice Judaism in secret, found their way to mercantile centers across Europe and the New World. They were, after all, a well-connected, well-educated, and well-capitalized bourgeoisie, ideally suited to play the role of middlemen in the emerging global economy. It is no wonder that conversos sailed with Columbus—a durable legend has it that Columbus himself was from a Jewish family—or that Kritzler finds thriving Sephardic communities in Jamaica, Brazil, and New Amsterdam. Wherever the Spanish or Dutch planted their flags, at least some Jews were sure to follow.

And at least a few of those Jews were actual pirates. At a time when the boundaries between war, commerce, and piracy were highly porous, it was easy for Jewish sailors and shipowners to mingle peaceful trade missions with privateering. Take Samuel Palache, a descendant of Moroccan rabbis who started his career of international intrigue as a trade representative, exchanging Moorish jewels for Spanish beeswax. He tried to enter the service of King Philip III of Spain, even offering to convert to Catholicism; when the offer was declined, he signed up with Philip’s deadly enemies, the Dutch, and began running guns from Holland to North Africa. As part of this campaign of harassing the Spanish, Palache once led a fleet to attack Spanish shipping in the Mediterranean; and while the result of this expedition is not reported,” Kritzler admits, it is enough for him to grant Palache the dashing nickname The Pirate Rabbi.” (Even so, the reader cannot help noticing that he never set foot, or sail, in the Caribbean—Kritzler’s title is more catchy than precise.)

Kritzler even stakes a Jewish claim on one of the marquee names in pirate history, Jean Lafitte—the patriot buccaneer who ran a smuggling empire from New Orleans in the early nineteenth century, then redeemed himself by fighting with Andrew Jackson against the British in the War of 1812. Kritzler quotes Lafitte himself on the importance of his Jewish ancestry:

My grandmother was a Spanish-Israelite. . . . Grandmother told me repeatedly of the trials and tribulations her ancestors had endured at the time of the Spanish Inquisition. . . . Grandmother’s teachings . . . inspired in me a hatred of the Spanish Crown and all the persecutions for which it was responsible—not only against Jews.

The oppressed becomes the foe of oppressors, the beaten-down Jew takes up a cutlass: it is an irresistible story-line, and the central premise of Kritzler’s book. If Lafitte’s confession seems to illustrate it almost too conveniently, that may be because it is almost certainly fictional. According to his notes, Kritzler found the quotation in a book about the history of Jewish New Orleans, where it is cited from The Journal of Jean Lafitte, a book published in New York in 1958. Nowhere in his text or notes, however, does Kritzler mention what it took me only moments to find out on the Internet, that The Journal of Jean Lafitte was the work of a notorious forger named John Laflin, who claimed to be a descendant of the pirate, and who also invented documents related to Davy Crockett and Abraham Lincoln. There is no way of telling, from Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean, whether Kritzler thinks he has a good reason to trust the Journal anyway, or if he is even aware of its true provenance.

The Lafitte example is a minor one—he appears on only two pages of the book—but it is unfortunately typical of Kritzler’s way with historical evidence. Kritzler relies heavily on the work of reputable historians in putting together his picture of Jews in the New World in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But wherever there is a gap in the evidence, he is more than happy to fill it with wild speculation. Particularly unsettling is his practice of treating as true the desperate admissions of conversos put to torture by the Inquisition—as when he refers, admiringly, to the Brotherhood of the Jews of Holland, “a clandestine group dedicated to fighting the Inquisition,” whose “existence was revealed in the tortured confessions of four convicted Judaizers.” Evidently Kritzler believes as strongly as Torquemada in the power of the rack to elicit truth.

Suffice it to say that Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean concludes with Kritzler’s claim to have discovered the location of a secret gold mine belonging to Christopher Columbus on the island of Jamaica, where Kritzler lives. He even reproduces a seventeenth-century code allegedly pointing to the exact location of the mine, and invites “the first reader” who cracks it “to join our quixotic search.”

Kritzler is welcome to his gold mine, and I hope for his sake that X does the mark the spot. But the quixotic search he has really embarked on in Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean is a less innocent one. His book is the latest product of what might be called the “Tough Jews” school of history-writing, after the 1998 book by Rich Cohen. Cohen’s book was a paean to Jews like Arnold Rothstein and Meyer Lansky—murderers and gangsters, or, as Cohen lovingly described them, “Jews acting in ways other than Jews are supposed to act, Jews leaving the world of their heads to thrive in a physical world, a world of sense, of smell, of grit, of strength, of courage, of pain.”

By flattening out the immensely complex story of the conversos and their motives into a straightforward parable of freedom-loving, Spain-hating Jewish buccaneers, Kritzler is catering to the same American Jewish thirst for examples of Jewish toughness. “Forget the Merchant of Venice,” he writes, “his New World cousins were adventurers after my own heart: Jewish explorers, conquistadors, cowboys, and yes, pirates.” I get it; I grew up riding the Pirates of the Caribbean at Disneyland. But there is something strange about the way American Jews, the most secure, prosperous, and assimilated Jews in history, keep returning to tales of Jewish violence and thuggery to affirm their potency. Jewish pirates, like non-Jewish pirates, were basically killers and thieves, and often slave-traders to boot. Surely there are enough examples of courage in Jewish history—physical and also moral courage—that we don’t need Samuel Palache to prove that Jews, too, can be brave.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.