Death of a Ladies’ Man

Phil Spector was psychotic and abhorrent. Here’s why his art still matters.

It was August of 1963, and Brian Wilson was driving around LA. He had every reason to feel giddy: The album he’d just released with his brothers and his cousin, Surfin’ U.S.A., hit the No. 2 spot in the charts, placing him, at 21, in the company of Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, and the Beatles. But his songs, he knew, were variations on a theme, a medley of interchangeable fast riffs and fun you could brush away as easily as the sand on the California beaches that gave his band its name. He was looking for something more. And then, he turned on the radio.

A song came on, a new song he’d never heard before. It started with a drum beat—boom boom boom pah, kick kick kick snare—that was every bit the sonic manifestation of fate knocking at the door as anything ever conjured by that other Beach Boy, Beethoven. Then, all hell broke loose: castanets, two guitars, two bass guitars, two saxophones, a trombone, a full orchestra, and a woman, Ronnie Bennett, singing. She didn’t sound as sure as, say, the Shirelles, or as playful as the Crystals, the girl groups dominating the early 1960s scene. She sounded like a woman doing her best to hold back tears. The lyrics matched her mood: “The night we met I knew I needed you so,” she sang, “and if I had the chance I’d never let you go.” By the time she hit the refrain, pleading with her man to be her baby, Wilson couldn’t take it any longer.

“All of a sudden it got into this part—‘be my, be my baby’—and I said ‘What is—what?! Whoa whoa!’” he told an interviewer decades later. “I pulled over to the side of the street, to the curb, and went, ‘... My God! ... Wait a minute! ... No way!’ I was flipping out. I really did flip out. Balls-out totally freaked out when I heard. ... In a way it wasn’t like having your mind blown, it was like having your mind revamped.”

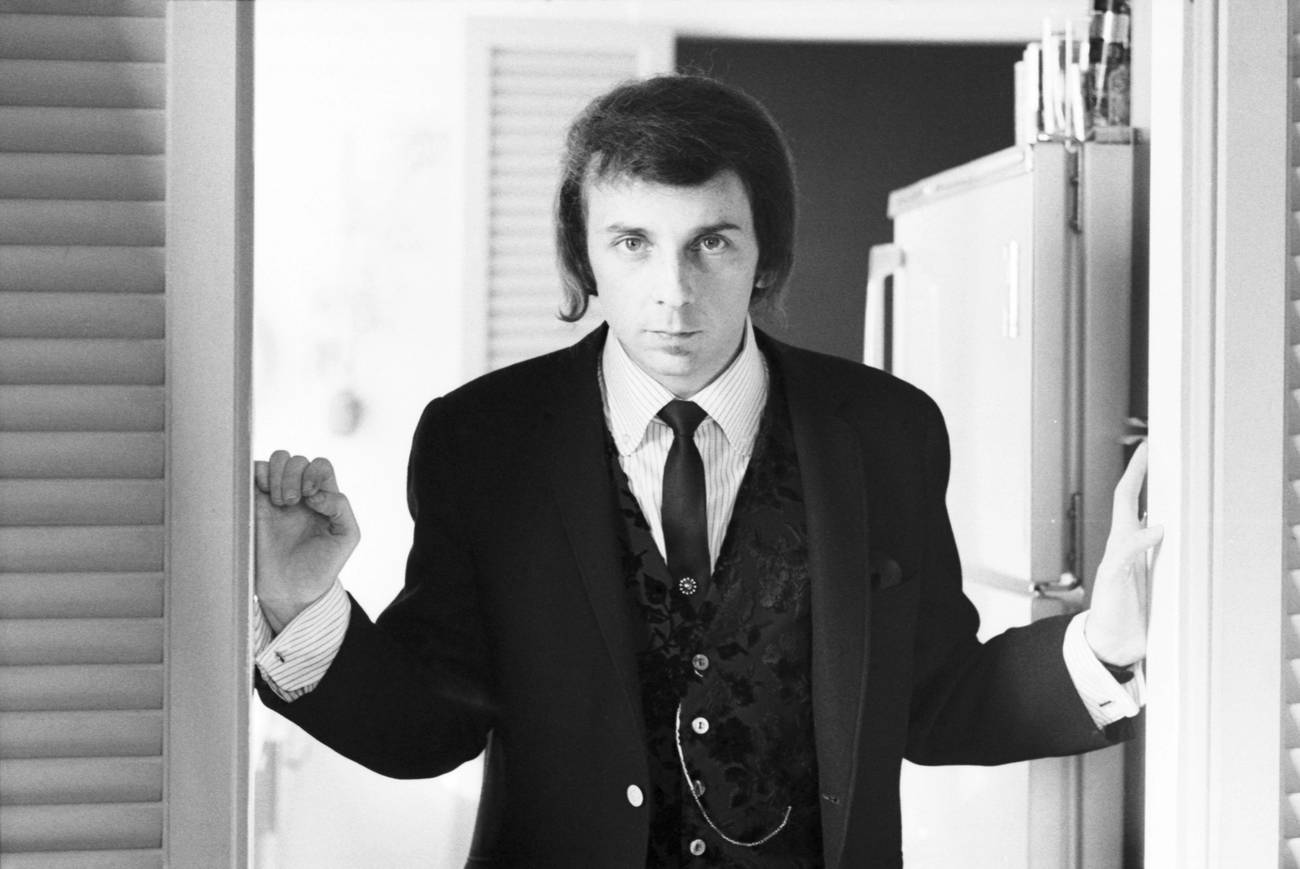

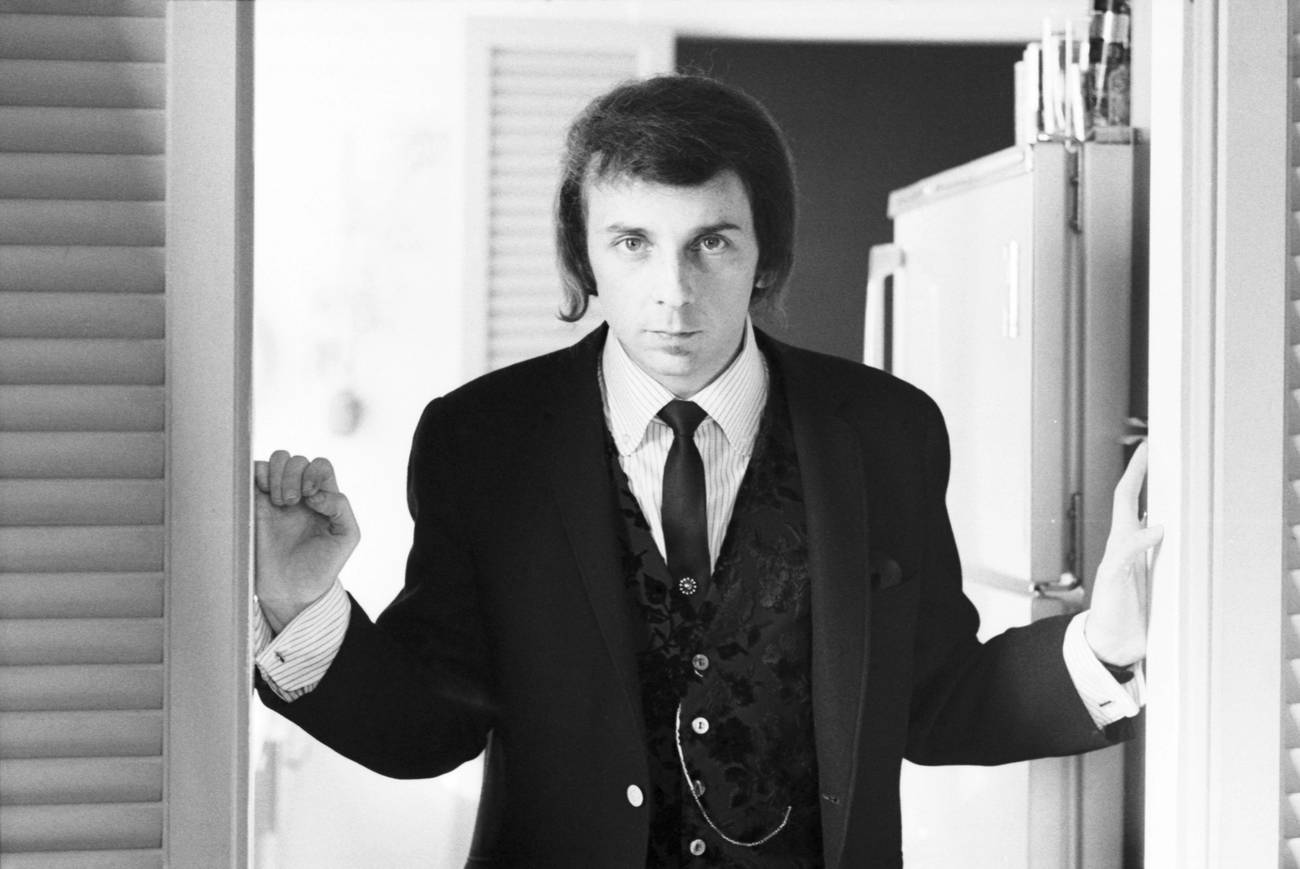

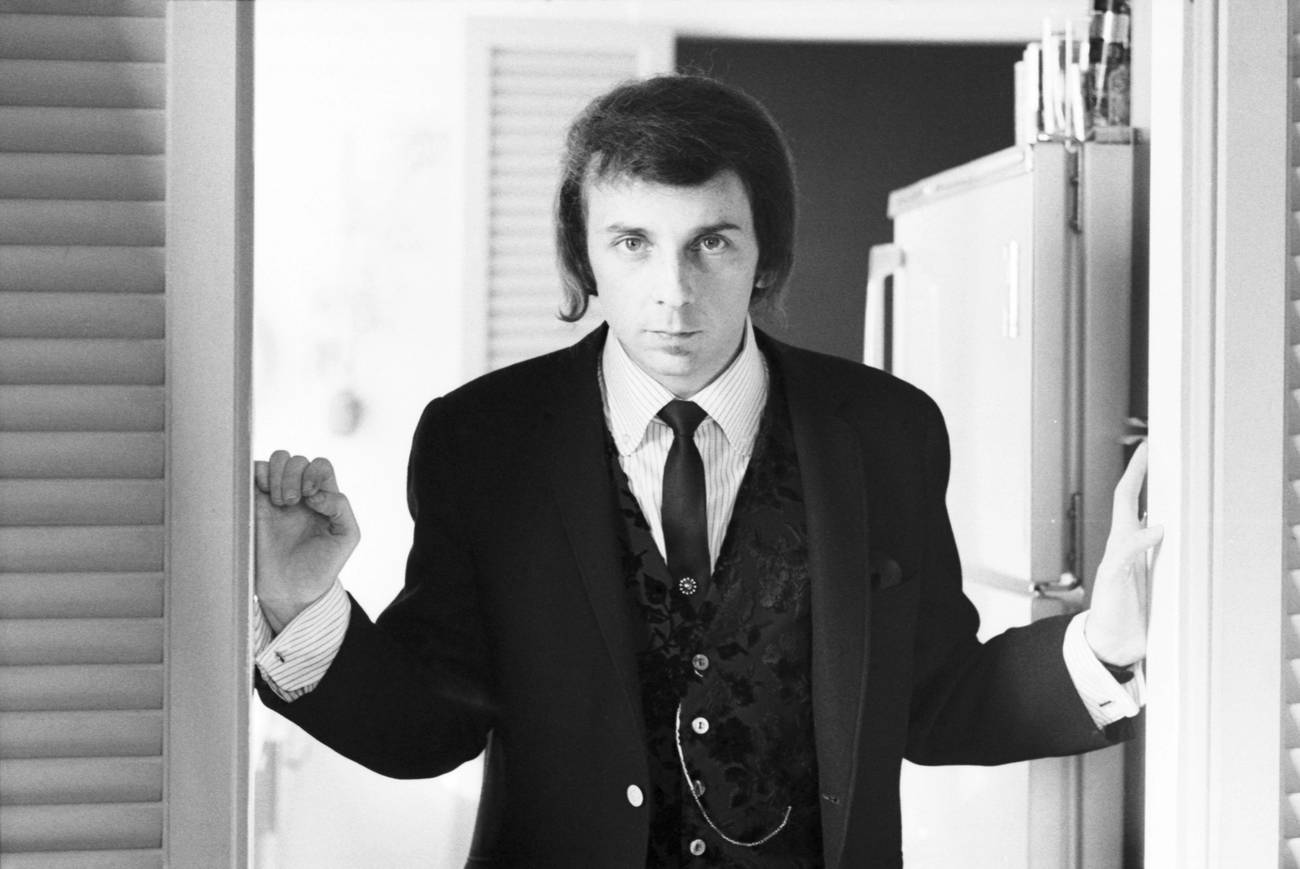

The man who wrote and produced that song, Phil Spector, died last week at the California Health Care Facility, a state prison for inmates with medical or mental needs. After decades of shaping American music as a songwriter, producer, and pop auteur who played other artists until they produced the sounds he’d heard in his head, he was serving a sentence of 19 years to life for the 2003 murder in the second degree of actress Lana Clarkson, a conviction that took half a decade and one mistrial to materialize.

It is tempting, given Spector’s celebrity and the sordid circumstances of his later years, to send him off with a slow shake of the head, saying something banal about how tragic it is that genius so frequently courts excess. That would be a disservice to one of our greatest artists, who deserves, after a lifetime of demanding the same, to be understood on his own terms. And, shorn of the sound and the fury of a culture no longer particularly interested in depth, the story Phil Spector’s life, art, and death tells is one of a Jew trying and failing to find a home in the United States.

Maybe it was all to be expected of a child born on Dec. 25 and referred to by his mother, only half jokingly, as the second coming of Jesus Christ.

His father was Gedajle Spektus, who arrived in America on the steamship Cleveland with a third-class ticket and a declaration that his profession was a dry goods merchant, served in World War I, and then migrated to California to work in construction. Now going by George Spector, he married a woman named Bertha Spector, who may very well have been his cousin, and on Christmas Day, 1939, the couple welcomed their son, Harvey Philip.

He was adored and doted on by his parents and his older sister. He was also severely allergic to sunlight, overweight, and asthmatic, which meant that afternoons were mainly spent around the house rather than outside, playing with friends. This suited Bertha just fine: People, she told her youngest, were not to be trusted, a lesson that Jewish history had proven right for millenniums.

When Phil did venture out among his peers, it was never as an equal. “There was a game called pitcher, batter, catcher, which you’d play with a stick and a ball on the streets,” he recalled later in life. “And when I was a kid it was a joke that ‘Joe, you’ll pitch; Jack, you’ll catch; Jim, you’ll hit; and Phil, you’ll produce the game.’ That was how I achieved my success, because I was smarter than most.”

Such begrudging participation might’ve served Spector just fine. But early on the morning of April 20, 1949, his father drove his car a few miles away from his home, parked outside, connected a tube to the exhaust pipe, placed the other end next to him in the driver’s seat, rolled up the windows, turned on the engine, and sat there quietly until he asphyxiated and died. On his tombstone, the family placed a large Star of David and a sentence that would continue to haunt his son for decades: “To Know Him Was to Love Him.”

Once chubby, Spector, depressed and withdrawn, grew thin. By the time he entered Fairfax High School, he could not have looked more antithetical to his popular peers: They were tall and tanned and easygoing, passing the time riding around in cars and playing sports; he was scrawny and short and weak, felt deeply uneasy about being Jewish in a sea of gentiles, detested the outdoors, and took comfort in almost nothing.

Except, that is, for music: For his bar mitzvah, his mother bought him a guitar, which unlocked his natural and uncanny gift for music. Soon, he’d joined the school band—his teacher told anyone who’d listen that Spector had taught him much more than he’d ever taught Spector—and got himself elected Town Crier, a position that involved leading the school’s choir in song. But he might’ve not ever considered that music could be more than a pastime had his mother and sister not taken him, for his 15th birthday, to see Ella Fitzgerald play live. Spector cared little for the singer; instead, he was watching the guitarist standing behind her, moving his fingers along the instrument’s neck and producing sounds that Spector had never heard before. He was further astonished to learn that the musician, Barney Kessel, the only white player in the otherwise all-Black band, was, like himself, a Jew, and, like himself, a scrappy, self-taught talent who bought a guitar with his paper route proceeds as a child and picked up chords by listening to the radio.

Obsessed, Spector pinned a photo of Kessel to his bedroom wall, alongside his other idol, Albert Einstein. When a music magazine dared name another player as the greatest ever, he wrote a fierce letter defending his hero. Moved by the act, his mother and sister contacted Kessel, and arranged a meeting. Sitting across from the man he idolized, Phil was too nervous to say anything, but he listened as Kessel described what a career in music might look like. By the time Kessel was done talking, Spector couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

What was it like working with Phil Spector? Leonard Cohen was curious. Exhausted after a long tour, and as hungry as always for a touch of transformation, he turned to the producer and suggested they collaborate.

Spector had started off the 1970s well. After a brief reclusive period, he reemerged to assert his claim on the sound of pop, producing Let It Be for the Beatles, Imagine for John Lennon, and George Harrison’s masterpiece, All Things Must Pass. In March of 1974, however, he crashed his car in Hollywood, flew through the windshield, hit the ground, and was so badly hurt he required nearly a thousand stitches in his head and face. To cover his disfigurement, he began wearing wigs. To cope with the trauma, his behavior became more erratic than ever. When he first invited Leonard and Suzanne for dinner at his house, he flew into a rage when the couple, tired after a long meal, got up to leave, and ordered his servants to lock the doors. The Cohens remained seated, surrounded by Spector’s armed guards, imprisoned in the producer’s dimly lit mansion. They were only freed in the morning.

This is what happens when America’s sunny disposition meets Judaism’s sobriety, forged by seeing a hundred empires rise and fall and a thousand promises made and broken.

His insanity aside, there were many other plausible reasons why Cohen should not have collaborated with Spector. The latter was, in Tom Wolfe’s memorable phrase, “the first tycoon of teen,” the man who piled up the ooh-las to create scores of hits for the young and the restless; the former was the sort of artist who sought inspiration in liturgy. And Cohen’s albums, his most recent being the exception, were spare, while Spector’s approach to record production was known as the Wall of Sound, in which brigades of musicians battled in the studio and delighted in hearing their notes bleed into one another to create an overwhelming musical totality. Cohen and Spector, however, shared not only a manager, but also an infatuation with popular music in all its varieties, and an obsession with the intricacies of the songwriting process. To that end, a partnership was proposed: Cohen would write the words, Spector the music. Each man would be relieved of his weakness and allowed to concentrate on his true passion.

The two began working in earnest, often spending entire nights in Spector’s home. Cohen noted the eccentricities of his new partner—it was impossible not to—but enjoyed the process nonetheless. “He really is a magnificent eccentric,” he said of Spector in an interview, some years later. “And to work with him just by himself is a real delight. We wrote some songs for an album over a space of a few months. When I visited him we’d have really good times and work till late in the morning. But when he got into the studio he moved into a different gear, he became very exhibitionist and very mad.”

His madness was evident at first sight. As Cohen entered the studio in January of 1977 to begin recording the new album, he saw “a room crammed with people, instruments and microphone stands. There was barely space to move. He counted forty musicians, including two drummers, assorted percussionists, half a dozen guitarists, a horn section, a handful of female backing singers and a flock of keyboard players.”

Orchestrating this cacophony was Spector, standing behind his console, screaming, ordering people to do exactly as he said. Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg, who were brought in to sing background vocals on “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard On,” weren’t spared. Listening to his playback, Spector played the music so loudly that he caused the speakers to explode and had to relocate the entire session to another studio. He was perpetually drunk and never unarmed; others in the studio, including the bodyguards Spector insisted he needed, were similarly liberal about mixing drugs and weaponry. “With Phil,” Cohen recalled years later, “especially in the state that he found himself, which was post-Wagnerian, I would say Hitlerian, the atmosphere was one of guns, I mean that’s really what was going on, was guns. The music was subsidiary, an enterprise, you know people were armed to the teeth, all his friends, his bodyguards, and everybody was drunk, or intoxicated on other items, so you were slipping over bullets, and you were biting into revolvers in your hamburger. There were guns everywhere. Phil was beyond control. I remember the violin player in the song ‘Fingerprints,’ Phil didn’t like the way he was playing, walked out into the studio, and pulled a gun on the guy. Now this was, he was a country boy, and he knew a lot about guns. He just put his fiddle in his case and walked out. That was the last we’d seen of him.”

Cohen himself was not exempt from feeling the barrel. One night, at around 4 in the morning, as another session cascaded to an end, Spector stumbled out of his booth and into the studio. In one hand, he held a .45 revolver, in the other, a half-empty bottle of Manischewitz sweet kosher wine. He put his arm around Cohen’s shoulder and shoved the revolver into the singer’s neck. “Leonard,” he said, “I love you.” Not missing a beat, Cohen replied, “I hope you do, Phil.”

But Spector’s eccentricity in the studio wasn’t the real problem. Each day, accompanied by his armed goons, he would take the master tapes to his car and whisk them away to his house. He had done the same thing with Let It Be. He would mix the album as he saw fit, and present it to Cohen as a fait accompli. It was not an arrangement any artist would gladly accept, especially when there were signs suggesting that somewhere amid the fog of booze and bullets, Spector lost track of any vision he might have had for the album. “I’ll tell you something, Larry,” he wrote in a note he scribbled on the master tapes to his longtime engineer, Larry Levine, “we’ve done worse with better, and better with worse!”

Cohen’s fans, as well as some of the critics who reviewed the album upon its release, saw it as a farce. Here was Cohen’s delicate poetry drowned by sound, his voice barely audible on some of the tracks. They were right, but for all the wrong reasons. Musically, the album, Death of a Ladies’ Man, is a marvel. “Memories,” for example, is a grand doo-wop anthem, as well as a disquisition on pop history; it ends with a snippet from The Shields’ 1958 hit “You Cheated, You Lied,” which it closely resembles, and hearing the newer song melt into the older one delivers a brutal jolt of emotion. Here is doo-wop, two decades later, its promise all soured. It is sung now not by sweet-voiced youths but by a raspy sounding middle-aged man. The melody, too, is louder and more frayed, almost hysterical. The Shields’ song conveyed the genteel sadness of broken-hearted teenagers who grieved for an affair gone bad. They sensed, however unconsciously, that they had their entire lives ahead of them to fall in love all over again. Working with more or less the same tune, Cohen sounded desperate as he sang about walking up to the tallest and the blondest girl and asking to see her naked body. He cast himself as the same doo-wop crooner, 20 years older, realizing that heartbreak wasn’t a sweet and passing sorrow but a permanent state of being, seeking now sex and the relief of unbearable urges rather than romance and other fanciful emotions.

This, then, was the real problem with Death of a Ladies’ Man, not its musical styling but its spiritual message. Spector hadn’t just made Cohen sound different; he made him sound crass. Cohen himself admitted as much: playing “Memories” a few years later in Tel Aviv, he introduced the song with an apology. “Unfortunately,” he said, “for my last song, I must offend your deepest sensibilities with an entirely irrelevant and vulgar ditty that I wrote some time ago with another Jew in Hollywood, where there are many. This is a song in which I have placed my most irrelevant and banal adolescent recollections. I humbly ask you for your indulgence. As I look back to the red acne of my adolescence, to the unmanageable desire of my early teens, to that time when every woman shone like the eternal light above the altar place and I myself, was always on my knees before some altar, unimaginably more quiescent, potent, powerful, and relevant than anything I could ever command.”

Spector might’ve spoken the same words, had words been his medium. Listened to from the distance of decades, Death of a Ladies’ Man sounds more coherent than ever. That’s because it’s not really a clash at all: Singer and producer may be radically different in many ways, but both are powered by a similar engine, one that burns with longing and fueled by the maddening idea that no matter how hard you try, you can’t, as a Jew, ever feel truly at home in America.

What made Phil Spector feel perpetually uprooted and lost? It’s not just that he was a first-generation American who longed to be as seamless as his carefree pals. It’s not just that he was cerebral and insecure and fragile, qualities that had little value in the land of the pioneers. His form of alienation, arguably, was metaphysical, world-historical, and very Jewish.

In his fine Spector biography, Tearing Down the Wall of Sound, the journalist Mick Brown interviewed Ron Milstein, Spector’s closest high school friend. Even though the overwhelming majority of the student body at Fairfax High was Jewish, Milstein recalled that Spector felt unsafe, and demanded that he and his friend come up with goyish monikers. And so it was that Phil Harvey and Ron Mills sauntered into a Burbank party, blowing their cover a minute later when an excited Spector forgot all about the ruse and shouted “Hey, Milstein, get over here!”

The anecdote is telling, and it points the finger in the right direction: Whatever else he thought or knew or believed, Spector realized, on some sublimated level, that his failure to grow roots in California’s soil had everything to do with his old religion.

Judaism, even if you didn’t believe in it, plugged you right in to a dynamo of ideas and beliefs that were, upon examination, not very American. For all the Founding Fathers’ enthusiasm for the Hebrew Bible, if you were a sensitive child—and whatever else Spector happened to be, he was surely that—you understood that the perennially juvenile nation that interpreted divine election as invitation to grow big and hairy had very little in common with the perpetually aged faith that understood divine election to be a burden that can never be shaken off. Jews erred in the wilderness, forever looking for the promised land; Americans were expanding their city on the hill, the promised land reincarnate. America was a pledge to optimism; Judaism, to borrow a phrase from Leonard Cohen, was a manual for living with defeat.

How to handle this innate tension? How to create art that doesn’t fall apart at the outset, eager to please two irreconcilable masters?

Good artists—think Irving Berlin, or Philip Roth—went native, sublimating their anxieties into humor or whim and creating a body of work that gave the gentiles a flattering image of themselves, a frontier culture shaded by one or two layers of psychological depth and continental sophistication. Read Roth, for example, and you see the gentile’s imagination of the Jew’s imagination, a picaresque parade of exhortations and ejaculations, a superabundance of cock that, if you stripped it of its Yiddishist flair—all that Oedipal stuff, say, or the juggling of big ideas and small desires—was really just a postmodern twist on Whitman, an all-American sensibility stuffed with the stuff that is coarse and stuffed with the stuff that is fine. You could know nothing about Judaism and ingest Roth easily; like marshmallow bits in cheap cocoa powder, his evocations of Jewish tradition were just morsels of fluff designed to melt into the brew and enhance the flavor ever so delicately.

Great artists, by contrast, managed to largely avoid this same tension, either by wearing an endless string of masks, like Bob Dylan—who famously once acknowledged the essential insincerity of his public persona by stepping on a stage and telling his audience that he had his Bob Dylan mask on—or by creating characters that were simultaneously Jewish and universal. Like Saul Bellow: Augie March—“an American, Chicago born,” as he memorably declares himself to be—is forever seeking a better fate, which eludes him even as it rewards all around him because March, like all Jews, lives in and out of time, is of the world and foreign to it, exists in the here and now but also tethered to the messianic yearnings that inform and inspire him. That’s why he, proclamation of Americanness be damned, ends the novel living in France—a wandering Jew, he is forever roaming, forever escaping the inescapable.

It’s an elegant, and immensely moving, way to address the modern Jewish condition. But truly sublime artists realize that this tension, between the Jew and the world, cannot be avoided, escaped, sublimated, rephrased, or ignored. It had to be dealt with head-on, which is the core attachment that bound Leonard Cohen to Phil Spector. The former, having also lost his father at a young age, spent a lifetime seeking solace and wisdom in his tradition and learning how to impart it to others. It drove him to drink and to depression before allowing him to emerge, in his golden years, as a prophetic voice. The latter, on the other hand, was much more fragile: If he couldn’t be in the world, then the world might not be at all. This, in part, is why, when he married Ronnie Bennett in 1968, he imprisoned her in their house, and only allowed her to leave if she carried a life-size puppet of him wherever she went. It’s a monstrous act, of course, but also a heartbreaking one: Walk around feeling like you’ve got no home, and eventually even you could mistake yourself for a lifeless doll. This is what happens when America’s sunny disposition meets Judaism’s sobriety, forged by seeing a hundred empires rise and fall and a thousand promises made and broken: If you can’t hold the tension, you go mad.

Spector did. But there’s a terrible beauty to his carnage. “So won’t you say you love me?/I’ll make you so proud of me/We’ll make ’em turn their heads every place we go.” This might as well be a Jew singing to the America he knows he can never have, and his song can never be anything more than two or three minutes’ worth of heartbreak so profound no wall of sound can block out or dull.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.