Philip Guston: A Stumblebum in Venice

An off-track exhibit at the Accademia puts the New York School painter in the company of Titian, Tintoretto, and, weirdly, the Italian Nobel prize-winning poet Eugenio Montale

Philip Guston in Venice? Venice, Italy? At the Accademia, in close proximity to Titian and Tintoretto? It scares the Jewish mother in me.

The curator of this show has not only stuck Guston in the ancient sinking city inside a Roman Catholic museum abuzz with pietas, crucifixions, and other episodes from Season 2 of the Christian Bible, aka The New Testament, but he’s also cramped Guston’s style—his uniquely autonomous place in the narrative of post-1950s American painting—by placing him in a “crowded room” with five heavyweight and in some cases heavily anti-Semitic poets of the modern literary canon—a motley crew of literary gods with initials like T.S., D.H. and W.B.

But all of this was done with the best intentions by a curator named Kosme de Barañano, who has welcomed this outsider—a Jew, a stumblebum, a conflicted American comic-book artist from a scrappy clan of Depression-era Russian Jewish immigrants living in L.A., who went on to become the quintessential sage (and to some, traitor) of New York abstract painting before his death in 1980 from cigarettes (he was just 66).

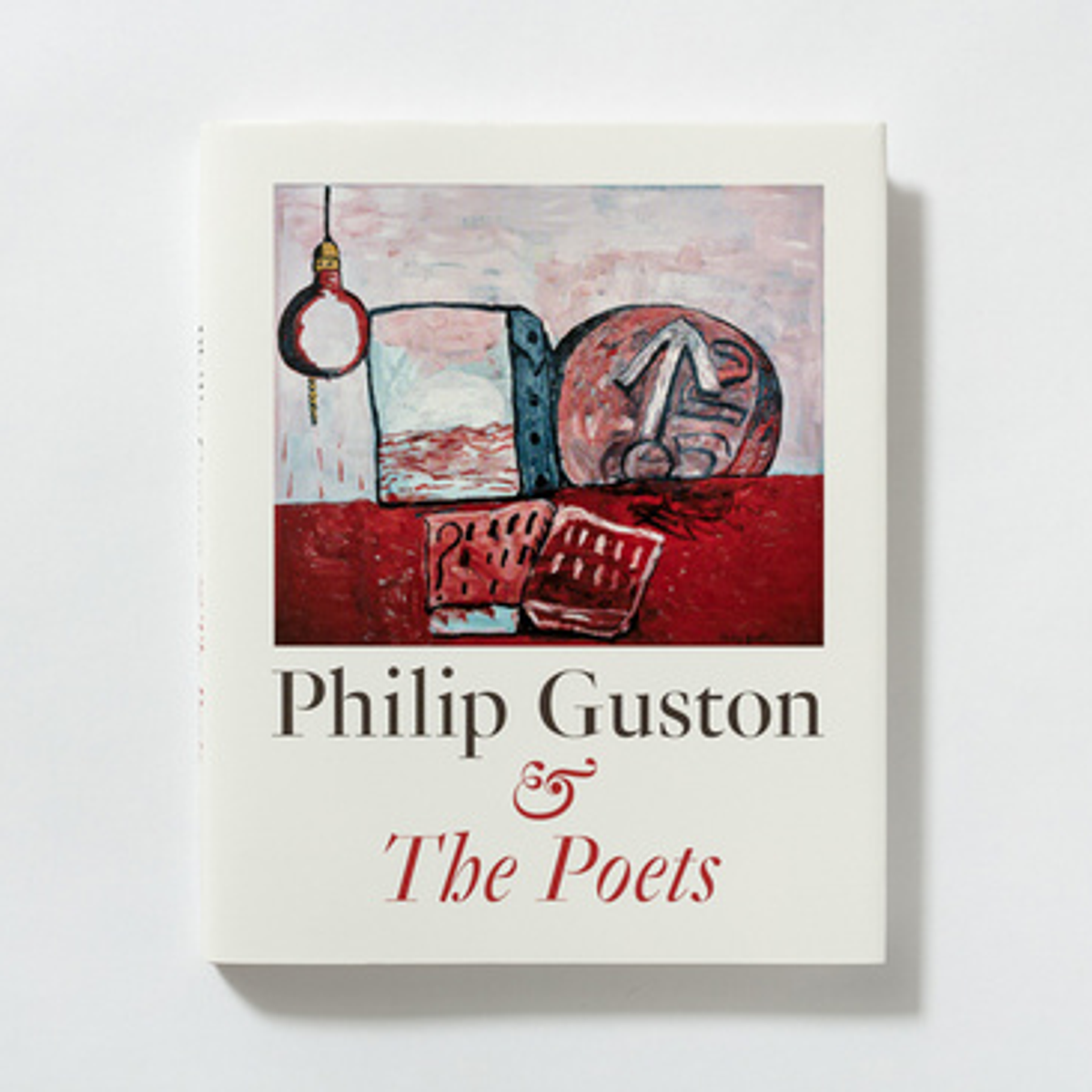

Barañano not only secured one of the holiest sites anywhere in the world for Guston’s dingbat brand of oil-on-canvas, but he also authored an elegant, no-holds-barred coffee-table book, Philip Guston and The Poets, which was published by the international Zurich-based gallery Hauser & Wirth. The book happens to be accompanied by an equally sexy and well-produced Guston monograph, Philip Guston: Nixon Drawings, 1971 & 1975—a trove of Guston’s most irreverent Nixon Drawings, which were also on view last season at Hauser & Wirth’s Chelsea gallery in a show wonderfully titled Philip Guston: Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975.

Darkly comic as the Venice exhibition and book may be, it is also burdened by the curator Barañano’s somewhat extravagant doctoral-ish thesis, which frames Guston through the verse of five poets. A better title for the show might have been “Guston and His Post-Humous Pallbearers”—there is something undeniably funerary about the affair, which connects Guston more to those who died before him than, say, those who are coming up in the next generation and who were probably not even born until after 1980.

Nevertheless, due to this unlikely high-rolling Italian/Swiss tag-team duo, the art world has found itself amidst an unprecedentedly Euro-Guston moment. I prefer the way Guston’s significant link to poetry was explored and essayed back in 1995, in a show (and catalog) at the Drawing Center titled Phillip Guston’s Poem-Pictures. This show focused on Guston’s many close relationships to poets, from his own wife, Musa McKim, to the poets he sparred with on the reg, like Clark Coolidge, Bill Berkson, Stanley Kunitz, and William Corbett. The Drawing Center’s show established Guston’s reputation not only as a personal acquaintance and a port in the storm to a great many poets, but—with his goofy childish lettering and repertoire of loosely cross-hatched objects (a cigarette wedged between two fingers; the dirty soles of men’s shoes seen from the eyes of a cobbler, a loaded flimsy paint brush, a ubiquitous blank canvas tacked down the edge with black nails; a hooded Klansman; a clock with ridiculous hands moving slower than time; a dangling naked light bulb; a hand holding out a trash-can lid like a shield in self-defense)—as Woodstock’s in-house illustrator.

My fantasy Guston show would locate the artist not in Venice or anywhere else in Italy but closer to home—in a dilapidated barn upstate, with a scratchy Bob Dylan LP playing on an old stereo as hairy hippie painters, beat poets, and even a few lanky cartoonists with protruding Adam’s apples gather around smoking cigarettes and leafing through scrapbooks of George Herriman comic strips clipped from the funny pages of vintage newspapers.

***

Kosme de Barañano’s Guston moment is less down-and-out and less down-to-earth. In his introductory essay published in the show’s catalog, de Barañano launches skyward into “five summaries of the drama of human destiny envisioned by five poets, the painter’s spiritual brothers.” The first of the brethren to get called up to the podium is W.B. Yeats, whose “agony of trance” (a term from his 1930 poem “Byzantium”) is less a depiction of a “domestic interior, a still-life, or an artist’s studio,” to quote Barañano, and more a depiction of “the poet’s mind itself, turning.” Indeed, Yeats’s poem conjures a Guston-like way of “bringing it alive,” but the poem’s animation feels less Zap and more Marvel or DC Comics. “That dolphin-torn, that gong-tormented sea.” Enter Aquaman or any superhero in aqua-blue spandex. Aqua blue, I’m afraid is not found in Guston’s palette; Guston’s animation is that of the anti-hero.

Barañano seems to get further off track when he claims that Yeats’s poems, like Guston’s art, both “symbolize a place of purification and refinement.” I see Guston less as a purifier and more as a corruptor. He was known to wipe out a finished painting after working on it for days when it would inevitably dawn on him that it was too resolved, too pat, too refined, too pure. He’d sit with the painting until contemplating a way to mess it up, to intoxicate it. He’d challenge himself to flirt even further with disaster and the real prospect of failure in order to conquer new ground.

When Barañano compares Guston to this very Irish poet, he wisely shifts from a painter’s sense of seeing to a poet’s sense of hearing. Guston, he articulates, “reaches the peace that Yeats says he hears ‘in the deep heart’s core,’ which comes ‘dropping slow’ from the ‘veils of the morning.’ ”

It’s a lovely sentiment but, again, I find it somewhat distorted. Indeed Guston was known for late nights alone in the studio, but I’d argue that his mornings (say, 3 a.m.) prior to stomping out that last butt and crawling into bed, were spent more in a state of exhaustion and delirium than inner peace and tranquility. But before any such debate might be had, Barañano leaps across a huge gulf to another poet—the Italian Eugenio Montale (1896–1981) who may be less famous than the other four poet-pallbearers in the book/show, but was the recipient of the 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature and is therefore no pushover. However, while Barañano calls Montale “the author closest to Guston,” he also admits, “we do not know what Guston read of the works of Montale.” He continues with a kind of scholarly disclaimer: “One would have to study Guston’s library to see which books of Montale he owned…”

Indeed. Perhaps Barañano could have done some homework before embarking on such a broad cross-cultural thesis. “I am convinced,” Barañano assures us, “that Guston knew the poetry of Montale…” For now, his conviction is all we have.

Barañano might well regard questions about the reading habits of the historical figure of the painter Philip Guston to be petty next to his attempt to build a deeper metaphysical bridge between the painter and the writer. He rigorously compares the emotional “fish bones,” if you will, of both Guston’s and Montale’s integral visions. Guston’s “Gaze gathers objects and feelings on the shores of memory.” The curator concludes: “These written messages are aromas that awaken one’s gaze towards that iconographic labyrinth that are Guston’s paintings, like keys that help us open the gate to the artist’s secret garden.” I think of Guston’s paintings more as a patch of concrete on a vacant lot or contaminated soil somewhere near purgatory than the literary gardens or mazes where we spy courtly lovers or speak with a friendly pope strolling the Vatican a la Jude Law in the recent HBO drama series The Young Pope.

Barañano goes to great lengths to show Guston to be a poet. And who would contest this? He is a painter among poets and a poet among painters. Take your pick. Or choose both. Barañano is correct when he refers to the Roman poet Horace’s Latin phrase “ut picture poesis,” which translates to: “As is painting, so is poetry.” But Barañano takes great liberties projecting onto a defenseless Guston his own pride of Italian letters, Montale. It’s not as if Guston’s love for Montale compelled him to learn Italian and travel to Italy just to find an out-of-print copy of the obscure poet’s 1925 opus, Cuttlefish Bones. There is simply no such myth. Too bad for Barañano.

Yet the show does get us to see Italy as Guston’s home away from home. Barañano not only paints a picture of Guston traveling to Italy “to escape the outcry” following one of his shows (which I will get into momentarily), and to flee from “the absurd and exhausting circle that abstract expressionism had become” to take “comfort from the Italian tradition of a simple iconography, the elements of everyday life, and the generosity of the ex-voto” (which I think is fairly preposterous).

Barañano does not explain what made the New York art-world so “absurd.” Was it the crowded field of second-generation abstract expressionists? Or the coming wave of Warhols? Whatever the case, I cannot fully accept an image of Guston, a salty New Yorker, soaking up the Italian quotidian while fulfilling his vows at the Accademia.

Whatever the truths of Guston’s life and art, the show’s PR has clearly been effective at inspiring the typical army of regurgitating internet journalists with zero acuity or chops to push the concept of Guston circa 1970 on the run, seeking a kind of poetic exile in Italy. The story goes something like this: Guston returned to Rome and Venice numerous times over the course of his career. In 1948, on a Prix de Rome, he lived for a year at the American Academy in Rome, making frequent trips to Venice to study the old masters. In a letter he sent to Bill Berkson, he wrote: “I am immersed in Quattro and Cinquecento painting more than ever! And when I go north, to Venice, faced with Tiepolo, Tintoretto, and even so-called ‘mannerist’ work like Pontormo, Parmigianino, etc., I cheat on my earlier loves and fall head over heels.”

It is clear that Guston did fall in love with Tintoretto (and I would add Titian, though he is not named in the letter), although his romance with these artists was not as much of a dalliance as a rigorous study. Guston would have surely been researching ways to reintroduce story telling into his art while reflecting on the very strong figurative elements of his own past back in the 1930s when he was a WPA muralist.

Tintoretto’s 1548 mural at the Accademia, The Miracle of the Slave (also known as The Miracle of St. Mark), is implicated here more than any other painting. It would seem it had direct influence (presumably via images in books) on a gigantic mural that Guston and his friend Reuben Kadish made on an interior wall of a converted baroque palace in Morelia, Mexico, in 1935 called The Inquisition. This mural—uncovered in 1973 after being hidden behind a wall for decades—depicts the struggle against terrorism, war, fascism, and the Spanish Inquisition. It’s a veritable mash-up of intolerance and racism, with Guston’s own “otherness” front and center (he and his parents had fled the Russia pogroms). But the lifeless figure in the foreground of the 1,000-foot-plus mural was also likely informed by Guston’s most gruesome memories from about 12 years prior (in 1923), when he discovered his father, Lieb Goldstein, who had suffered from extreme depression, hanging from a noose from the rafters of his shed.

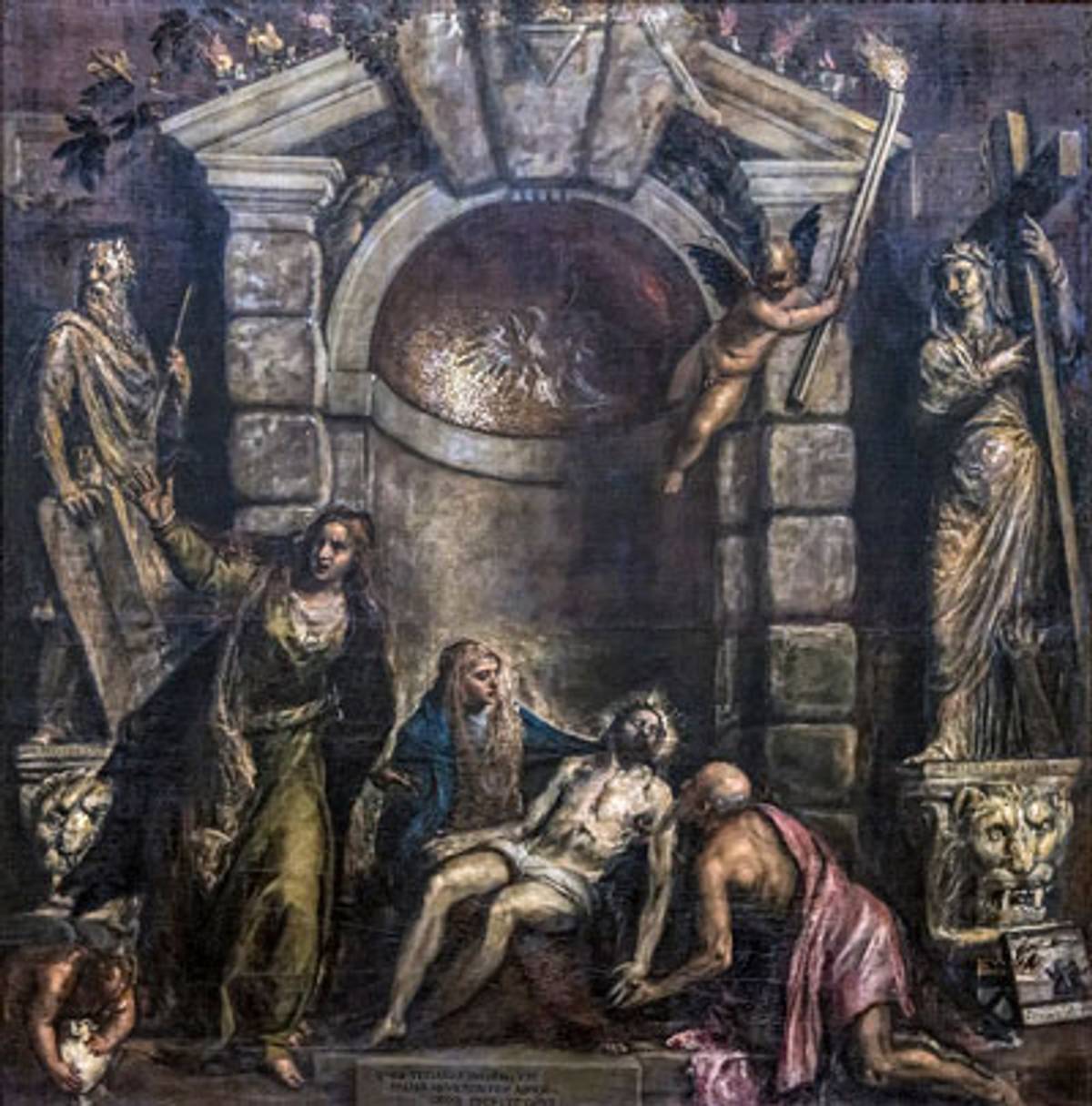

If the young Guston was inspired by Tintoretto even before seeing his work in the flesh, there is no doubt that after visiting the Accademia years later, the older Guston would have latched on to Titian, specifically to Titian’s last radical masterpiece, the Pietà (c. 1575). This painting breaks from all expectations of Titian’s clean, bright color and fleshy exuberance to reveal a level of murky pathos that shoots back and forth between the allegorical to the biographical. What at first appears to be a painting of a dying Christ can then be read as a self-portrait—Titian expressing his own mortality while attempting to secure, through barter and prayer, the permanent location of his tomb. The painting is made even more lively (or deadly)—more visceral—by the fact that Titian died before its completion.

It is an uncharacteristically cartoony painting for Titian, with a shallow depth of field, unrealistic figures set on blocky, crude architectural artifice. It looks like an awkward stage set; even its religious iconography feels in some way digressive. With its diagonal composition, he shows the steps from a dying martyr, Jesus Christ, to the Virgin Mary, to Mary Magdalene … but he keeps on going! All the way back to Moses, who stands there with his clunky 10 Commandments. Reaching into the painting toward Jesus, with his back to us, is the kneeling angst-ridden Nicodemus. Most art historians see this man as Titian himself. It is hard not to see the painter reaching into his own canvas, to brush white paint (i.e., light) across Jesus’ bare chest as he gasps for his last breath of air.

This brings me to the Pietà’s very Gustony bottom right corner. It features a small painting, seen from a three-quarter angle similar to the canvases that appear and reappear in so many of Guston’s late paintings. In Titian’s haunted painting-within-a-painting, he himself appears with his son Orazio who was also dying of the plague. Together both men pray to the Virgin Mary for a safe delivery to the afterlife.

***

In the ’60s, Guston returned to Venice, this time representing the American Pavilion in the Venice Biennale. But it was his third visit to Venice that became legendary. It was 1970, he was relaxing a few days after the opening of his show at Marlborough Gallery in NYC, when news came of a scathingly negative review in The New York Times by the paper’s senior art critic, Hilton Kramer. Kramer, who seems to have had a permanent bug up his ass, insinuated that Guston was a fraud—not only a trendy late-comer to ab-ex, “a colonizer rather than a pioneer … of Monet-Mania,” but even worse: a sellout, an insincere practitioner of a new cartoony style. According to Kramer, Guston was inauthentic, a “mandarin masquerading as a stumblebum.”

Guston was supposedly “angry for about half an hour” (his own words) before throwing the article in one of the canals. But the harshness of Kramer’s contentious words went with Guston to the grave, and have remained hanging in the air and in cyberspace ever since. “For in offering us his new style of cartoon anecdotage,” wrote Kramer (in what sounds to me like an alcoholic rant), “Mr. Guston is appealing to a taste for something funky, clumsy and demotic. We are asked to take seriously his new persona as an urban primitive. … The spectacle of Mandarin sensibilities masquerading as unlettered but lyrical stumblebums is now universally recognized as a form of artifice that deceives no one—except, possibly, the artist who is so out of touch with contemporary realities that he still harbors the illusion his ‘act’ will not be recognized as such.”

Guston’s defense, which he expressed in a later interview was simple: “I wanted to tell stories!”—stories which did undermine the trembling sensitivity he was known for with, what critic Peter Schjeldahl once called “interiors ajumble with liquor bottles, cigarettes, food, and painting gear.”

I would say that Guston was bringing it all back home. I would also say that Kramer was a racist pig who clearly didn’t want to know about any “funky … urban primitives.” His rant also seems to border on anti-Semitic. He calls Guston a “sacred figure” to his devoted followers, making paintings that were “almost more religious than aesthetic.” Why not just come out and call the guy a dirty rabbi?

Schjeldahl once summed up Kramer as a critic who “gloried in attack” with a “sturdy allegiance to old ideals of high culture” and whose “intellectual compass was set, from early on, to…” of all people … drumroll … T. S. Eliot—(the fifth, Barañano would have us believe, of Guston’s spiritual brothers).

Kramer did, however, get one word right, as elitist and pejorative as it was: stumblebum, which I read, with irony, as having been spot on. If Guston were alive today, he’d probably wear a T-shirt saying “I’m a stumblebum & damn proud of it!” That’s just my hunch. Perhaps antagonistic words written by embittered critics are the real poetry surrounding Guston’s paintings. Perhaps these are the words we should be scrutinizing, not the words written by poets who were focused on their own vague horizons of despair.

Barañano, regardless, turns our attention to another of Guston’s so-called spiritual brothers, D.H. Lawrence, a despairing writer who probably would have been at home on Hilton Kramer’s book shelves (close to Eliot’s Wasteland) but not as at home in Guston’s shtiebl. In the following passage, Lawrence gets tangled up in his own attempt to express the importance of being visionary. “I believe one can only develop one’s visionary awareness by close contact with the vision itself: that is, by knowing pictures, real vision pictures, and by dwelling on them, and really dwelling in them.”

But why look to D.H. Lawrence for a description of self-discovery when we have Guston himself, who was not exactly moot? “We have terrible arguments going all night for weeks and weeks,” Guston claimed in a fascinating 1966 interview. “I make a mark, a few strokes, and I argue with myself … ‘Is that what I mean? Is that what I want?’ But there comes a point when something catches on the canvas, something grips on the canvas. I don’t know what it is.” While Lawrence dazzles and deceives himself with attempts at saying what he means and meaning what he says, Guston just calls it as he sees it: “I don’t know.”

Strained as his thesis may be at times, Barañano does do a nice job of shedding light on Guston the existentialist groping in the dark. This best comes across through the American poet Wallace Stevens, who writes in one poem “The Sail of Ulysses” (published posthumously in 1989).

For this creator is a lamp

Enlarging like a nocturnal ray

The space in which it stands, the shine

Of Darkness, created form nothingness

Such black constructions, such public shapes

And murky masonry, one wonders

At the finger that brushes this aside

Gigantic in everything but size.

Indeed, one can see Guston in this poetic construction site, with its “murky masonry” and paradoxical rays of darkness. Stevens could be describing Guston himself when he writes in another essay, quoted by Barañano, about his daily sense of falling short: “Humble as my actual contribution may be and however modest my experience of poetry has been, I have learned … the incalculable expanse of the imagination as it reflects itself in us and about us. This is the precious scope which every poet seeks to achieve as best he can.”

Barañano misses certain key details in his own murky masonry. He all but misreads one of Guston’s paintings. “The fingers draw a line on the red plane at the bottom. Two fingernails, two amputated fingers, and a missing thumb. The hand functions alone like a lightning bolt; it descends from the cloud and creates its shadowless icon, the line.” I see this same painting’s arm and veiny hand extending from the clouds with paintbrush as a celebration. The hand is not missing fingers due to amputation; they are simply curled at the knuckles. To me this is obvious. Guston seems to be pondering his own hand, the way he holds the brush, the way he achieves his tender touch. It is not a painting about a gory, butchered, disembodied hand, but a meditation of the strength that even an old man can still have in his body. Like the Paul Simon song, “Still Crazy After All These Years,” this stumblebum is amazed by his own wear and tear, his own longevity and perseverance.

***

By this point, Barañano’s thesis is primed for brother No. 5: T.S. Eliot. In a way, everything in the show centers around the painting Guston made of Eliot on his deathbed—a painting from 1979 called “East Coker-Tse” that hangs alongside lines from the poem that supposedly inspired it, Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” which open with the famous lines: “In my beginning is my end…”

According to Guston’s daughter Musa Mayer, the painting by her father “is a death mask of Eliot, but also a kind of self-portrait. … He painted it after a heart attack that nearly killed him.” But this painting feels forced compared to Guston’s other bed paintings, where we feel for the painter himself, the immensely sympathetic protagonist who has carried his sloppy, greasy paint with him to bed dunking his haunted nightmare into the purity of his dreams. These paintings are so gruelingly empathic—one, for example, with a plate of cookies propped on his chest—that the painting brings out the nurse and or doctor in all of us.

But the Eliot death mask that has gotten top billing in Venice this summer is not one of Guston’s better paintings. To me, it seems like it is working hard to hit home the curator’s thesis that Guston and Eliot were in bed together.

But to give Eliot full consideration, let’s return first to his anti-Semitism. In an article that recently appeared in The New Yorker, “Shakespeare’s Cure for Xenophobia: What ‘The Merchant of Venice’ Taught Me About Ethnic Hatred and the Literary Imagination,” the literary historian Stephen Greenblatt helps us experience Eliot’s oozing Jew-hatred on Venice’s Rialto:

A lustreless protrusive eye

Stares from the protozoic slime

At a perspective of Canaletto.

The smoky candle end of time

Declines. On the Rialto once.

The rats are underneath the piles.

The jew is underneath the lot.

Eliot’s poem looks back to Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, with its fascinating study of the history of Venetian Jews in finance. But the author admits that he developed a crush on Eliot’s poetry after “the greatest living poet in the English language and a winner of the Nobel Prize” gave a reading at Yale University when Greenblatt was a student there in the 1960s.

Regardless, Eliot’s anti-Semitism is typical; it is his language that really counts. Eliot’s poetry makes me think of a different poet, a Jewish poet, who is perhaps closer in spirit to Guston, the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan. In “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” Dylan wails:

Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters

Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

Where the executioner’s face is always well-hidden

Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten

Where black is the color, where none is the number

And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it

Then I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

Perhaps Dylan is Eliot unleashed—Eliot with his tie loosened, his blazer off, his shirttails untucked, and his suspenders hanging down. And his hair messed up.

Could it be that Guston (aka Philip Goldstein) and Dylan (aka Robert Zimmerman) are real spiritual brothers? The comparison seems all the more apt now that Dylan has won the Nobel Prize, a landmark in the constant dialectic of lowbrow contamination. The writer Alex Ross commented on the generational snobbery of the literati when he described the disconnect of a student in the 1960s writing a forward-looking doctoral thesis on “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” while old poets like W.H. Auden, when asked about Dylan were responding coyly: “I am afraid I don’t know his work at all.”

If we descend the staircase from Eliot to Dylan, we reach the underbelly of American pop culture and see the true inspiration behind Guston’s late work: the cartoonist George Herriman (1880-1944), who was not Jewish but was of mixed race and, like many Jews of that era, passed as a white guy by keeping on a hat at all times to cover the ’fro. Herriman, who came from a Creole background, moved to Los Angeles and was discovered William Randolph Hearst, who gave him the chance to make his 1910 comic strip, Krazy Kat, which grew out of an earlier strip called The Dingbat Family.

In his article “The Genius of George Herriman,” Adam Gopnik wrote about the 33-year-old George Herriman who “solved the problem of evil” when he introduced Ignatz the mouse into his comic strip Krazy Kat. Gopnik explains how Herriman created “a world in which evil existed as a source of necessary energy but didn’t cause suffering.” Ignatz, “with the gaunt form and gimlet eyes of a sewer rat, isn’t mischievous, like his sanitized shadow, Mickey Mouse—he’s wicked. No destructive or aggressive impulse is foreign to him, and his obsessive anger finds its everyday outlet in his desire to throw bricks at the dreamy and innocent Krazy, a divine idiot who chooses to see in Ignatz’s nastiness an expression of love.”

It was with bricks of honesty that Guston managed to knock art off its high horse.

I see him up in Woodstock, New York, sitting in front of a painting in process, studying and reflecting on the previous evening’s work. The chain smoker uses each cigarette as a clock—a means to measure the minutes, to tap time into the ashtray. The cigarette is the smoker’s hourglass. But if Guston is a reader, he reads Guston. If he brings a poet to bed with him, that poet is Guston. In his paintings, he paints a book again and again. But there are no words, no alphabets—just rows of simple vertical marks, the type of marks a prisoner makes as he counts out the days. Guston’s book is a wordless book bobbing in eternity. It doesn’t know what it says or what it means.

***

Read more of Jeremy Sigler’s art criticism for Tablet magazine here.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.