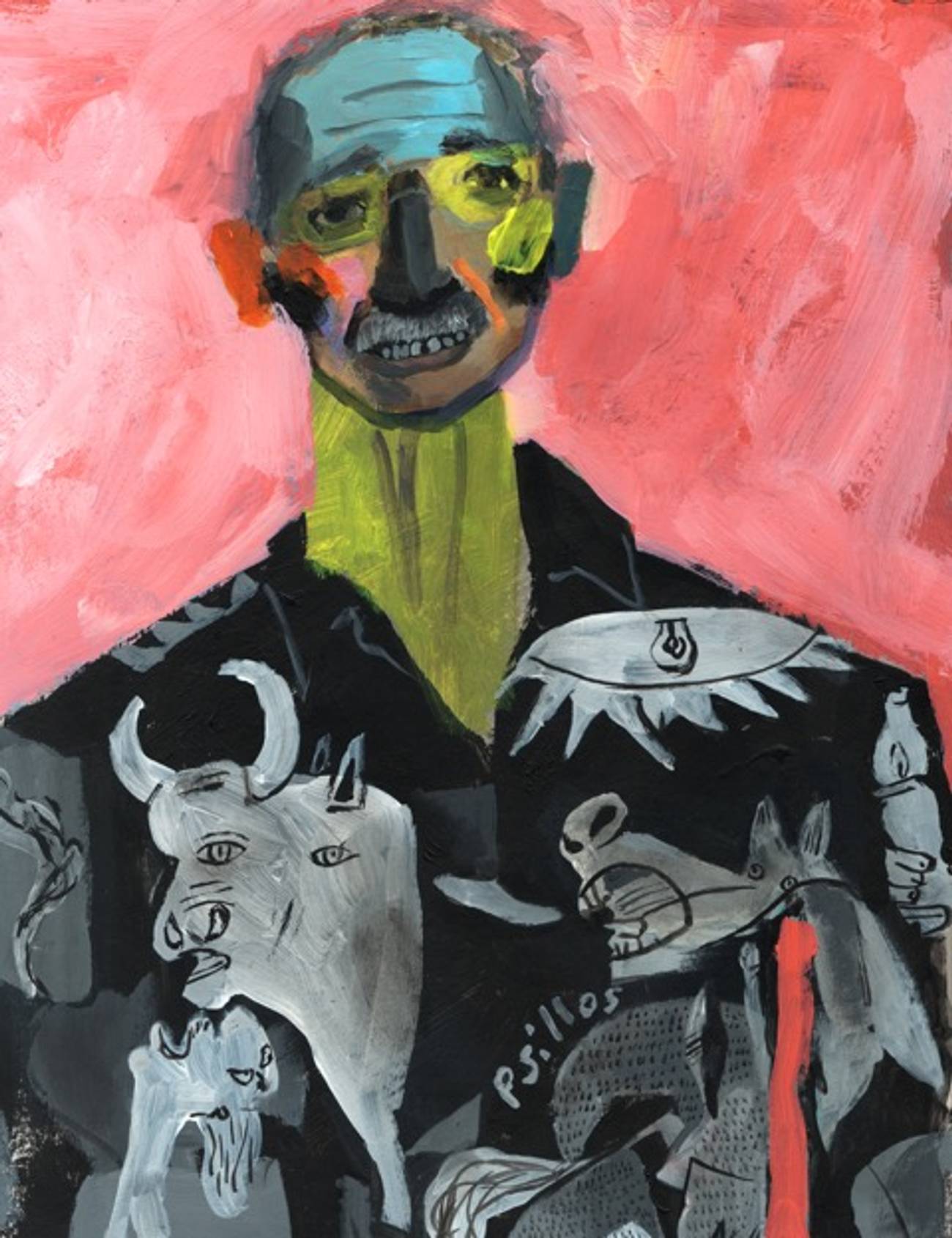

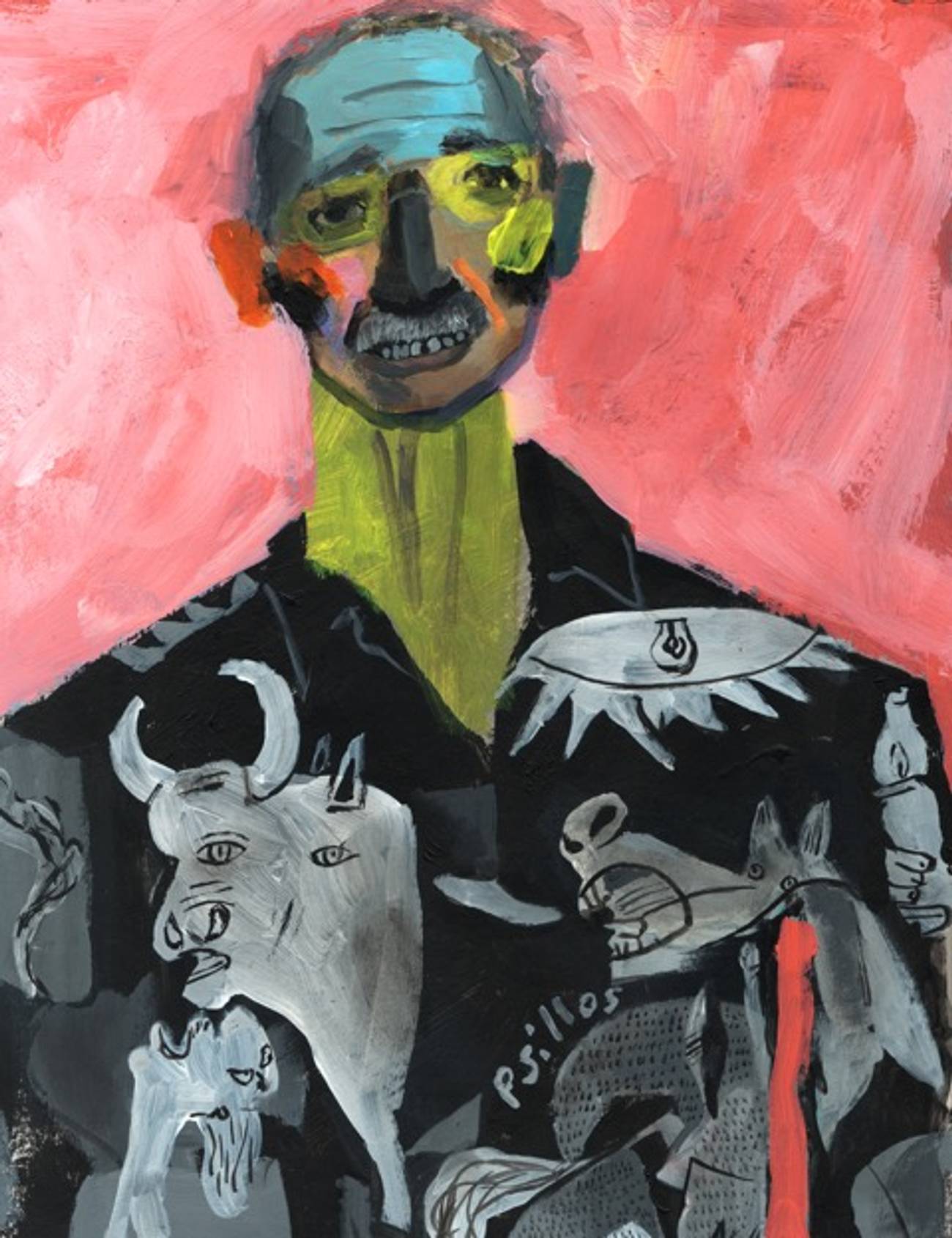

On Philip Levine, the Workingman’s Poet

Detroit, the Spanish Civil War, and the yearning for a perfect society

The late Philip Levine was officially appointed Poet Laureate of the United States in 2011, but I prefer to think of him as the once and enduring Poet Laureate of something smaller, which is a particular and narrow strand of thought and emotion, old and traditional in American literature, and not widely understood. His broad narrative themes are, of course, industrial and proletarian. He sings of Detroit from its days of auto-factory glory:

A winter Tuesday, the city pouring fire,

Ford Rouge sulfurs the sun, Cadillac, Lincoln,

Chevy gray …

And he is the poet of workaday exhaustion and routine:

Under the blue

hesitant light another day

at Automotive

in the city of dreams …

He seethes at the oppressive realities of factory life, and sometimes he waves an angry fist, which might lead you to suppose that, in bourgeois and snobby America, he must have been and must still be a major provocateur. But America is not really so bourgeois and snobby. Songs of Labor was Whittier’s book title in 1850. Proletarianism in poetry has always been the height of American respectability. I will grant that over the years it has sometimes been odd to discover Levine’s horny-handed odes to the nightshift laid out like pastries in the creamy columns of The New Yorker. But The New Yorker has never been as prissy as its page layout might lead you to suppose.

The arguments he arouses have mostly had to do with verse structure. Margalit Fox composed Levine’s obituary in The New York Times in 2015 and put it this way: “His work was not to every critic’s taste. Because of its strong narrative thrust, frequent autobiographical bent, and tendency to shun conventional poetic devices, some reviewers dismissed it as merely prose with line breaks.” But this raises a question. A lot of poetry can be read as prose with line breaks. The Greeks and Romans wrote in sentences. Their sentences follow the laws of prosody, which means that poetry is the result. But if you want to read it as prose, you can do so. There is the case of Carl Sandburg, who might be regarded as Levine’s principal ancestor among the Americans—a poet on Midwestern industrial and proletarian themes, who is thought to have written free verse.

Sandburg did not always write in sentences, but, even so, he produced a series of poems that, if you were to remove the line breaks, would pretty closely resemble a certain kind of newspaper story—the 750-word sentimental human-interest feature, weepy over some tough-as-nails, big-hearted member of the working class. Kenneth Rexroth observed this aspect of Sandburg long ago, and did not mean to be entirely dismissive. Some of those human-interest features are pretty good, and they are definitively poems. They obey a distinctive metrical system, or almost a system, which happens to have been Sandberg’s invention. He was a man of the modernist avant garde, in his manner, and he cocked his ear to the slang and jingles of the day, in search of novel rhythms and an alternative cadence, and he found what he was looking for.

Levine does something similar, with a difference. If you were to remove the line breaks from Levine’s poetry, certain of the poems would reshuffle themselves into impeccable sentences, and you would discover the same kind of catch-in-the-throat portraits of salt-of-the-earth working people that were Sandburg’s specialty, at roughly the same length, too, suitable for the tabloids. Sandburg in his poetry looked to the future, though. He was a friend of Ezra Pound; he wanted to extend the reach of poetry. With Levine I have the impression that he is looking to the literary past. Sometimes he writes in a conventional free verse, but more typically he composes short lines that appear only at first glance to be free verse, and then turn out to be toying with traditional structures of one sort or another. Is he counting syllables? Occasionally he does seem to be doing so.

He plays with terza rima, without the rima. He establishes a two-foot meter, or three-foot, or four-foot, and sometimes the four feet, stretching their toes, expand into blank verse, give or take a few stimulating irregularities. In the opening lines of a poem called “I Was Born in Lucerne,” he responds to the absurdity of his title:

Everyone says otherwise. They take me

to a flat on Pingree in Detroit

and say, Up there, the second floor. I say,

No, in a small Italian hotel overlooking

the lake …

—which is a nice feat, humorous, relaxed, and conversational, even while establishing a classical meter, before launching into a few variations.

A poem about a Detroit employment line, “What Work Is,” begins:

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Fort Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is—if you’re

old enough to read this you know

what work is, although you may not do it.

Is this an example of a poet shunning “conventional poetic devices”? It is true that in lines like these Levine shows very little interest in producing the kind of compressed or heightened phrases that we think of as “poetic.” The tone is intentionally and insistently and even showily flat. Sometimes the tone is flat unintentionally. A few lines later in the same poem, he comes up with, “Feeling the light rain falling like mist,” which would be tolerable if we had the impression that, for a line or two, his inventiveness had merely run out of energy. But there is a sentimental gas in Philip Levine. It spurts upward in his portentous concluding lines, one after another: “A strange star/ is born one more time;” “even the dead are growing old;” “in a last chant before dawn”—with my examples drawn from a small section of his New Selected Poems.

A poem like “What Work Is” nonetheless displays a fine anger and an authentic sympathy. The anger and sympathy swell into a kind of grandeur. And the grandeur imposes on his conversational phrases a stately pulse. He appears to be writing a pedestrian prose, which, because of the artful line breaks, also appears to yearn for something more. He is muttering about factory life and dreaming of Keats. And all the while the tone of voice remains (here is the charm, when he is at his best) natural and unpretentious.

Back to the Detroit proletarianism. It is entirely to the point that, now and then in the vignettes of industrial labor, he likewise presents us with a yearning, which is normally undefined. We feel the pressure of it:

Even before he looks he knows

the faces on the bus, some

going to work and some coming back,

but each sealed in its hunger

for a different life, a lost life.

But what is the different life, the lost life? Levine wrote a volume of autobiographical essays, The Bread of Time, which I read in hope of discovering the answer to this question, only to come away thinking that he made a mistake in writing the book, or perhaps I made a mistake in reading it. His poetry conjures an insistent myth of himself, “Phil,” the weary friend of the Detroit proletarians, who has somehow been plunked down in world history amidst rumors of World War II and the glamour of the European avant garde—Phil, with variable siblings (so far as I can judge) and a humble past and some kind of unexplained wound from the past that causes him eternally to groan. In The Bread of Time I expected to discover a fuller elaboration of the mythological background—maybe something like the landscape of Rexroth’s An Autobiographical Novel, with its Midwestern portraits of louche characters, pickpockets, gangsters, tramp bohemians, failed prostitutes, jazz musicians, emigré Marxists, and Bug House Square and the Dill Pickle Chicago arts scene.

But The Bread of Time is anti-mythological. It offers a picture of Levine climbing the ladder of academic success. An occasional jazz musician wanders across the page, and even so I was dismayed. He recounts his experiences as a classroom student of John Berryman and Yvor Winters, which he found to be thrilling—though both of those people seem to me, in Levine’s account of them, professorial blowhards, keen on intimidating their worshipful young disciples. He recalls with admiration the student triumphs of Donald Justice, his comrade in the poetry seminars—Justice, whose technical skills were flashier than his own. But from these people he cannot have derived his ideas about proletarian yearnings.

He tells us that he grew up in the Jewish middle class in Detroit, which in those days happened to be the national home of American anti-Semitism, courtesy of Father Coughlin, the fascist radio priest. And Hitler was in the newspapers. But Jewish ideas, sacred or secular or Yiddishist, do not seem to have stirred his soul, not even in their schoolboy sidewalk version:

My twin brother swears that at age thirteen

I’d take on anyone who called me kike

no matter how old or how big he was.

But it wasn’t true. “I only wish I’d been that tiny kid.” More significant for his intellectual development were his experiences, at age twenty-five, in 1953, toiling on the night shift at Chevy Gear and Axle—at the very moment when he was beginning to compose verse.

It is natural to wonder if he didn’t go through some kind of Marxist phase. This would have been pretty normal in the auto plants, and equally so in the Jewish neighborhoods. The Spanish Civil War broke out when he was eight years old, and he recalls that young men from the neighborhood volunteered to fight, which suggests that, in those corners of Detroit, recruiters from the Communist Party may have been out and about. But The Bread of Time makes clear that Communism was not his own inclination. Did he take an interest in any of the other factions of the Marxist Left, the tiny parties and micro-movements that caught Rexroth’s sophisticated attention? Detroit was the world center of post-Trotskyist splinter groups (the Johnson-Forest Tendency, the News and Letters Committee, the Facing Reality group), whose memberships included some notably talented people. The post-Trotskyists cultivated an idiosyncratic shop-floor journalism, which tried to show that tiny disputes with the boss or the supervisor reveal a yearning for a “different life,” and someday the yearning is going to generate a revolution in the name of the different life—a proletarian revolution that possibly might break out later this afternoon, or maybe in five hundred years but, in either case, is on its way. Isn’t this Levine’s theme? He says nothing about the tiny Marxist groups. He did write a poem about Trotsky, which is one of his auto-mythological poems.

The left-wing political current that figures in the autobiographical essays and famously in the poetry is mostly something else, older and quainter than Trotskyism and its splinter groups. This is the ancient current of proletarian anarchism and its syndicalist or anarcho-syndicalist trade-union agitations—a labor anarchism that, in Detroit, got its start in the long-ago 1890s. By the time Levine was coming of age, half a century later, the old tradition had pretty much retreated to the realms of nostalgia and the recollection of wounds. Still, old-timers were around—the Detroit Wobblies, from the old Industrial Workers of the World, who clung to their One Big Union even after the United Auto Workers had proved to be a bigger union; Russian anarchists and syndicalists with memories of the 1910s; the Refrattari groups of insanely refractory but no longer young Italians; the Grupo Libertad of Spanish exiles; and many another foreign-language group, I am sure, in the crazy-quilt immigrant zones. Detroit was not a provincial town. Levine says that, at his neighborhood dry cleaner, he got to know one of those old-style anarchist exiles, perhaps someone from the Grupo Libertad, who mesmerized him by saying pop-eyed things like, “Some day this will all be ours”—a man with a sublime sense of dignity, which was the anarchist style.

But the anarchist movement appears to have caught his imagination in a big way only many years later, after he had left Detroit. This was in 1965, when he had already ascended into a modest academic career at Fresno State in California. He took a sabbatical leave and, with his young family, went to live for a while in Spain. Generalissimo Franco, the despot, was firmly in command, but the cost of living was low. Levine studied Spanish. And he fell in love with the romance of Spain, which is vast—with the Spain of Antonio Machado and his melancholy drunks and tragic guitarists and palpitations of the spirit under the moonlight in Castille; and the Spain of Miguel de Unamuno and his plaintive and lucid Catholicism. He fell still harder for George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia—for Orwell’s account of Barcelona and its role in the civil war of the 1930s and the Spanish anarchists. These people, the anarchists, were the members of the Spanish Libertarian Movement (the anarchists in Spain were fond of the flexible and attractive word “libertarian”), which consisted of a sizable feminist organization and a sizable Libertarian Youth organization and a gigantic labor movement, the National Confederation of Labor-Iberian Anarchist Federation, or CNT-FAI. Franco crushed those several organizations when he won the war, and he slaughtered the members or jailed them or drove them into exile in France and Latin America. But Levine, in the course of his studies and sightseeing, kept stumbling on memories and legacies of the old movement.

The civil war had come about because, back in 1936, the Spanish Republic was drifting pretty far to the left, and Franco and his allies on the far right could not abide it. In July of 1936, Franco announced a coup d’état. The army rallied to his side, together with the church. And, one day later, the CNT-FAI called for an uprising against the coup. The anarchist trade unions and their allies poured into the streets. Whole city neighborhoods and farm villages joined the uprising, which meant that large parts of Spain fell into the hands of the anarchist organizations. The anarchists in Spain adhered to the political doctrines of the grand Russian theoreticians of the anarchist cause, Bakunin and Kropotkin, and, with no one to stop them, they went about achieving what Bakunin and Kropotkin had always advised. This was the program from Kropotkin’s book, The Conquest of Bread. They collectivized the factories and farms under the administration of their own unions. They did their best to abolish the capitalist class and the land-owning class. They intended to abolish the state, without entirely succeeding. They went as far as they could go to abolish the church (and they went too far: they staged massacres). A positivist delirium was their own religion. They worshipped reason and science. They celebrated the principles of social solidarity, artfully mixed (in theory) with the principles of tolerance. The virtues of labor were their own virtues. It was a program for a new civilization. A proletarian revolution? The mass uprising against Franco in July 1936 was the purest example of such a thing that has ever occurred. It was an amazing development. A utopian outbreak.

Disillusionment: the modern mark of a superior intellect—not the disillusionment that leads to drunken despair, but the disillusionment that leads to sobriety.

Now, it is true and it is curious that, at the time, the utopian development tended to be visible chiefly in Spain and only partly in other countries. In 2014 the French writer Lydie Salvayre published a half-novel, half-family memoir of the amazing event called Pas pleurer (or Don’t Cry), which won the Goncourt Prize—and in the course of the book she wonders about this particular quality, the revolution’s semi-invisibility. She attributes it to the ideological proclivities of the age. Franco’s proclivity was to picture his coup d’état as a nationalist and Catholic crusade against Soviet Communism, which led him to rant about the Spanish Communists, who were not very numerous, and to leave unmentioned the much-larger anarchist movement (though he was keen on slaughtering anarchists). And Salvayre blames the French intellectuals. The intellectuals in France were nicely situated to speak about the Spanish war and the revolution and to make everything known to the wider world. But their own proclivities were pro-Soviet, and, exactly as with Franco, this led them to overlook the anarchist side of the story. The Spanish Socialists and republicans had their own reasons to keep quiet about anarchists in their midst. I would add that maybe the anarchists were not too good at telling their own story. The proletarianism of the Spanish Libertarian Movement was too pure by half, and friendly intellectuals were hard to come by. José Peirats and Abel Paz, militants of the CNT, became pretty good historians after the war. I admire Peirats’s Estampas del Exilio. Especially I admire his biography of Emma Goldman, the American anarchist (who played a more prominent role in the Spanish war than any other American, and goes unmentioned in all the English-language histories). But the Spanish anarchist writers were never able to reach a wide audience. Nor could the anarchists in other parts of the world do much to publicize the Spanish events. In the United States the Freie Arbeiter Stimme and a journal called Vanguard and a few other libertarian publications did their best, but this did not add up to much.

Lydie Salvayre presents Pas pleurer largely as the old-age recollections of her mother, now an elderly Spanish exile in France–her mother who recalls that, when she was a teenager, she threw herself into the anarchist revolution in her village. And she made her way to Barcelona, the revolutionary center, and sat at the cafés on Las Ramblas and noticed that anarchist revolution was an intimate event and not just a political event—a transformation of simple and personal customs of deference and social hierarchy. Also a transformation of sexual customs—which naturally leads to the mother getting pregnant: a turn of the plot.

Salvayre describes her mother’s brother José, a militant of the anarchist cause—except that, after a while, the brother grows a little alarmed at some of the anarchist atrocities. José worships the most charismatic of the leaders of the Iberian Anarchist Federation, who is Buenaventura Durruti, the pistolero:

Durruti was his ideal, his wife, his literature, his need for adoration, Durruti the insubmissive, Durruti the pure, the guide, the generous, Durruti who attacked the banks, who kidnapped judges, who seized the armored car filled with the Bank of Spain’s gold to support the striking workers at Saragossa, Durruti who was imprisoned often, condemned to death three times, expelled from eight countries.

This is precisely what Philip Levine stumbled across in the Spain of Generalissimo Franco in 1965: the lingering underground legend of Buenaventura Durruti. In one of his poems Levine comes upon an old café of Durruti’s from the 1920s:

In this café Durruti,

the unnameable, plotted

the burning of the Bishop

of Zaragoza, or so

the story goes

And he comes upon some old remarks of Durruti’s, which I will quote at length because they give a flavor of the anarchist revolution—though mostly I will quote the remarks because, in one poem after another, Levine echoes the same words, sometimes acknowledging Durruti by name, sometimes not. He quotes those same remarks in The Bread of Time, too, as if to make sure that nobody among his readers will miss their significance to him. The remarks come from 1936, in the early days of the revolution. Durruti was interviewed by the Toronto Star. He said:

It is a matter of crushing fascism once and for all. Yes, and in spite of the government. No government in the world fights fascism to the death. … We know what we want. To us it means nothing that there is a Soviet Union somewhere in the world, for the sake of whose peace and tranquility the workers of Germany and China were sacrificed to fascist barbarians by Stalin. We want revolution here in Spain, right now, not maybe after the next European war.

We are giving Hitler and Mussolini far more worry with our revolution than the whole Red Army of Russia. We are setting an example to the German and Italian working class how to deal with fascism.

The interviewer from the Star pointed out that, even if the anarchists won the war against Franco and the fascists, they were going to end up sitting on a pile of ruins. Durruti’s reply:

We have always lived in slums and holes in the wall. We will know how to accommodate ourselves for a while. For, you must not forget, we also know how to build. It is we the workers who built these palaces and cities, here in Spain and in America, and everywhere.

We, the workers, can build others to take their place, and better ones! We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth, there is not the slightest doubt about that. The bourgeoisie might blast and ruin its own world before it leaves the stage of history. We carry a new world, here, in our hearts. That world is growing this minute.

The best-known of Levine’s poems on anarchist themes is a tombstone ode called “Francisco, I’ll Bring You Red Carnations,” which recounts a visit to Durruti’s gravesite and that of another pistolero, Francisco Ascaso, a fellow leader of the CNT. In The Bread of Time Levine reproduces the poem in full, which may suggest that “Francisco, I’ll Bring You Red Carnations” was his proudest achievement, or at least one of them. It begins:

Here in the great cemetery

behind the fortress of Barcelona

I have come once more to see

the graves of my fallen.

Two ancient picnickers direct

us down the hill. “Durruti,”

says the man, “I was on

his side.” The woman hushes

him …

The poet, having arrived at the gravesite, addresses Francisco’s tomb:

Only the police remain, armed

and arrogant, smiling masters

of the boulevards, the police

and your dream of the city

of God, where every man

and every woman gives

and receives the gifts of work

and care, and that dream

goes on in spite of slums,

in spite of death clouds,

the roar of trucks, the harbor

staining the mother sea,

it goes on in spite of all

that mocks it. We have it here

growing in our hearts, as

your comrade said, and when

we give it up with our last

breaths someone will gasp

it home to their lives.

The city of God? This is Saint Augustine’s phrase. Levine does seem to have been fascinated by Catholicism, which is odd to consider, given the Spanish anarchists and their fanatical hatred for the Catholic Church. Levine’s English-language poems on Spanish war themes are in this respect a mirror of Paul Claudel’s French poems on the same themes—Levine, a nostalgic of the anarchists, faintly attracted to Catholic phrases and images; Claudel a stalwart of the Catholic Church, sympathetic to Franco and utterly enraged by the violent anarchists. And both of them, Levine and Claudel alike, the enemies of rhyme!

You might suppose that, in taking up a passion for Spanish poetry and the anarchists of the 1930s, Levine had finally left Detroit behind. But, on the contrary, he seems to have felt that, in Durruti and his comrades, he had found a political legend suitable for expressing the emotions that had come to him in Detroit. He takes pleasure in intermingling the defeated Spanish anarchists and the exhausted Midwestern workers. A poem of Detroit called “To Cipriano, In the Wind” begins:

Where did your words go,

Cipriano, spoken to me 38 years

ago in the back of Peerless Cleaners,

where raised on a little wooden platform

you bowed to the hissing press

and under the glaring bulb the

scars across your shoulders—“a gift

of my country”—gleamed like old wood.

“Dignidad,” you said into my boy’s

wide eyes, “without is no riches.”

Dignidad—which is not so different from Whitman’s Libertad. The poet continues, addressing the Cipriano of his childhood:

I was growing. Soon I would be

your height, and you’d tell me

eye to eye, “Some day the world

is ours, some day you will see.”

And your eyes burned in your fine

white face until I thought you

would burn. That was the winter

of ’41, Bataan would fall

—and so forth. “Some day the world is ours”: Here is the anarchist millenarianism, as expressed at Peerless Cleaners. There is a detail that most readers will not be able to interpret. Levine writes:

Soon the Germans rolled east

into Russia and my cousins died. I

walked alone in the warm spring winds

of evening and said, “Dignity.” I said

your words, Cipriano, into the winds.

I said, “Someday this will all be ours.”

Come back, Cipriano Mera, step

out of the wind and dressed in the robe

of your pain tell me again that this

world will be ours. Enter my dreams

or my life, Cipriano, come back

out of the wind.

The full name “Cipriano Mera” is not the name of a pants-presser at Peerless Cleaners, however. Cipriano Mera was still another leader of the CNT who went on to become a military leader during the civil war—and who, after the defeat, never did make his way to the United States, so far as I know. Levine’s poem, which pretends to be a reminiscence, turns out to be one more episode in his auto-mythology—a poem that presents the poet as a boyhood disciple not of a pants-presser in Detroit but of a main hero of the Spanish Libertarian Movement.

Levine’s Spain-and-Detroit anarchist poems struck me as wonderfully moving when I first read them, many years ago. I saw in them cryptic signals from the unknown continent of labor anarchism, which is the purest leftism of all leftisms, rendered this-worldly and appealing by the poet’s prosaic tone and his downbeat appreciations of workaday life. Today, when I go back to those poems, the sentimental gas sometimes wafts in my direction, and I lose heart. “Enter my dreams/ or my life, Cipriano, come back/ out of the wind” is the sort of thing that Antonio Machado might have warned him against. I prefer Lydie Salvayre’s French novel. She remains sober. She admires her anarchists, and she sees the distinctive quality in them, the radiant faces of saintly commitment, a visible beauty. But she also appreciates the kind of lucidity that is sometimes described as disillusionment—the mortified lucidity of anarchists like her mother’s brother in the face of anarchist atrocities. And Salvayre appreciates the parallel disillusionment of a right-wing Catholic like Georges Bernanos, who appears in the novel and expresses his own indignation at the even worse and much larger right-wing atrocities, which Bernanos correctly understood were going to spread everywhere in Europe. Disillusionment: the modern mark of a superior intellect—not the disillusionment that leads to drunken despair, but the disillusionment that leads to sobriety.

But Levine captures something else, which is inebriation precisely, except in a version that is recalled instead of experienced directly—inebriation remembered through a prism of defeat and time and distance. The poems on anarchist themes amount to a memory of a memory of a yearning, which, regardless of my reservations, seems to me tremendously moving—the memory of the poet in the present recalling the defeated anarchists of yore as they recall their own past ideals and ambitions. Elegiac memories of a memory of a defeated leftwing millenarianism of long ago ought to count as a literary tradition in the United States, in a small way. “America I feel sentimental about the Wobblies,” wrote Allen Ginsberg, which pretty much captures the idea.

The master of this particular memory of a memory of a yearning was John Dos Passos in his novels of the 1920s, and then in U.S.A. in the ’30s, and still again in his novel of the Spanish Civil War, Adventures of a Young Man. Every few hundred pages in those novels Dos Passos introduces a grizzled veteran from the old defeated anarchist movements of America or France or Italy—one after another of those beaten-down comrades, each of whom has abandoned hope of seeing an anarchist revolution take place, and each of whom, as a matter of morality and backbone, goes on clinging defiantly, even so, to the old libertarian ideal of a proletarian civilization. The novelist William Herrick, who was badly wounded as an American volunteer in the Spanish war, conjures a similar memory in his novel ¡Hermanos! and in his autobiography, Jumping the Line. This is the memory of the magnificent defeated and their desires. It is a pathos. Philip Levine is the poet of this particular pathos—the poet of the left wing of the left wing of the past and its yearning for a perfect society, as conjured in a verbal cadence that yearns for a perfect meter.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.