A Photographer in the City: Garry Winogrand’s New Metropolitan Ironies

The Met’s dazzling retrospective declares: ‘It’s all a matter of how much freedom you can stand.’

New York’s chaos leads us to look away and hide inside ourselves. It’s impossible to fully digest the complexity of a city where more than a third of the residents hail from abroad, a city where rich and poor work side by side yet know little about each other. You can spend a whole day on its streets and in the end not remember a single person of the thousands you passed. To open your eyes and face—really face—this Moloch is daunting.

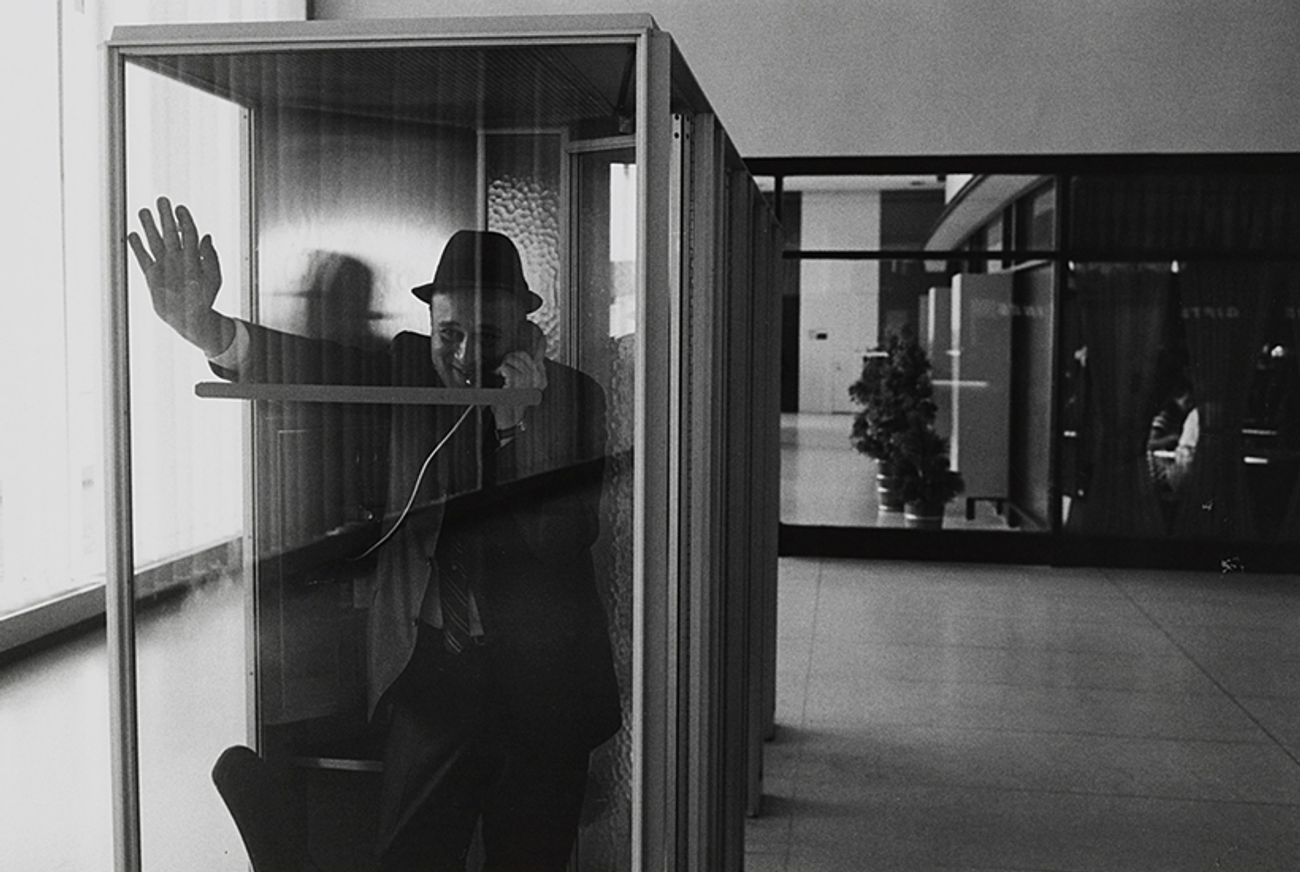

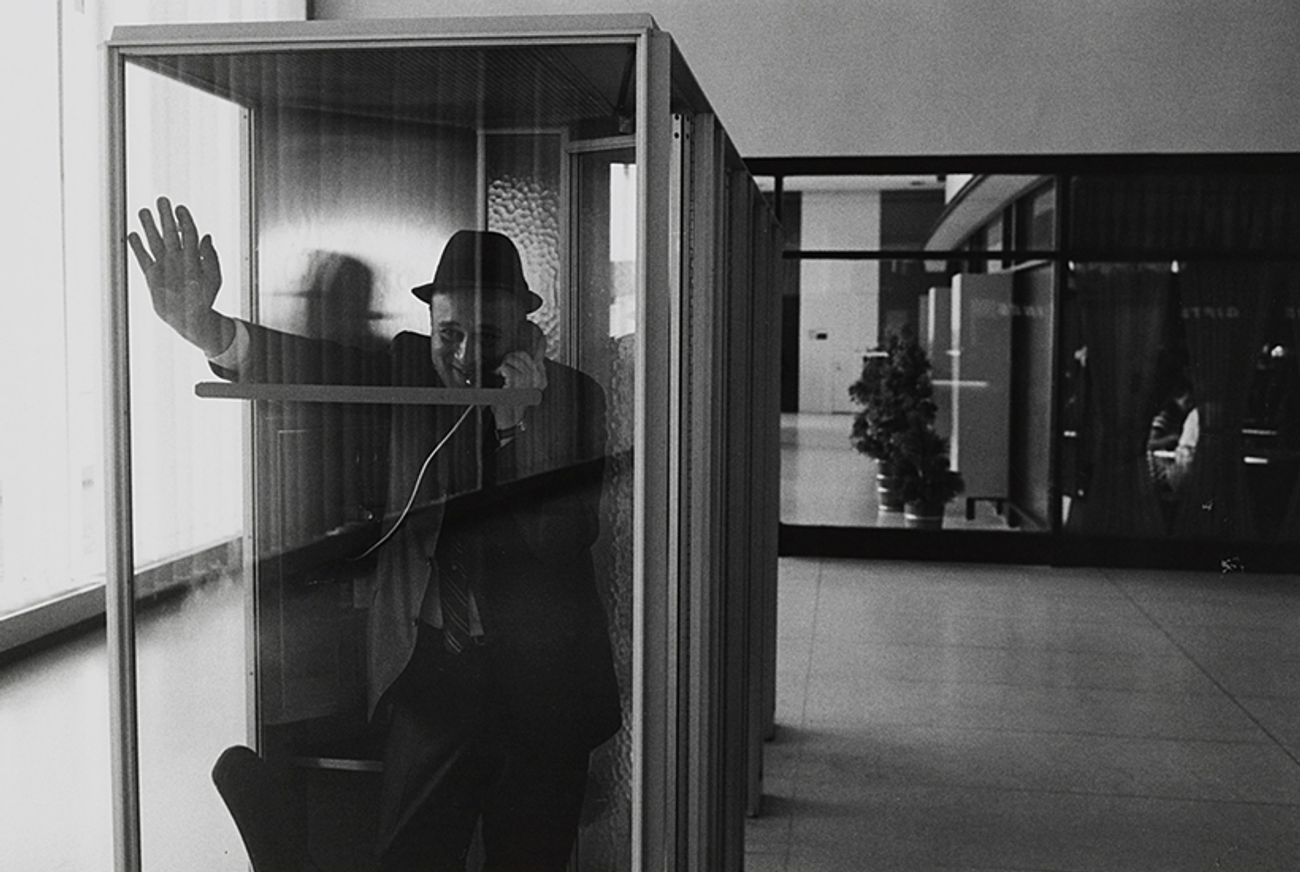

New York street photographer Garry Winogrand did face the city, day after day. When he died of cancer in 1984 at the age of 56, he had photographed approximately 2 million people and exposed some 26,000 rolls of film. In his snapshots we meet white, black, and brown people; cripples and beauties; the middle, working, and upper class; couples in love and peeping toms; children, old folks, animals, cops, and soldiers. His stage was the street, the airport, the train, and anything else in motion. “A walking raw nerve,” his third wife, Eileen Adele Hale, called him.

After his death, the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, Tucson, developed approximately 6,600 rolls of films (some 250,000 images) that Winogrand had left behind. Together with Erin O’Toole, associate curator of photography at SFMOMA, and Sarah Greenough, senior curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Winogrand friend and fellow photographer Leo Rubinfien reviewed thousands of contact sheets and chose a dazzling selection of 175 photographs that are currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of Rubinfien’s greatest accomplishments is that he didn’t compromise Winogrand’s anarchic approach by fitting it into neat categories and editing it to death. The confining—and somewhat nonsensical—category “Jewish photographer” is entirely absent. Rubinfien doesn’t seem interested in the fact that Winogrand was the son of eastern European Jews who was influenced by and friendly with Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and Lee Friedlander. Instead he honored his friend’s method. Winogrand had few rules, and there was little he wasn’t interested in. “Don’t drop your camera,” he is quoted as saying. “That’s my first rule of photography. In fact, it’s my only rule of photography.” And: “The world isn’t tidy; it’s a mess. I don’t try to make it neat.”

Despite the chaos emanating from Winogrand’s pictures, the three sections Rubinfien chose are specific enough to keep us from getting lost. “Down From the Bronx” chronicles Winogrand’s early years (1950-1971) and encompasses photographs taken primarily in New York. Stemming from roughly the same period, the pictures in “A Student of America” (which is how Winogrand described himself) were shot in New Mexico, California, Colorado, Wyoming, and Texas during the artist’s travels as a Guggenheim fellow. The last section, “Bust and Boom,” contains photographs that Winogrand took primarily in California and Texas during the last 13 years of his life.

While Winogrand’s prolificacy and his wide range of subjects can easily feel overwhelming, there is something oddly calming about his work. “I photograph in order to find out what things look like photographed,” Winogrand said. I think he meant that, for a moment, his pictures bring the hectic city to a halt.

As Winogrand peeks into a restroom at Kennedy Airport, he sees two 12- or 13-year-old boys cramming themselves onto a scale, weighing their skinny bodies together. The picture preserves a brief moment of intimacy and innocence that we know will soon vanish. Another shot shows a young couple making out in a grimy doorway. While the man is engrossed in the kiss, the girl glances over at Winogrand’s camera. A third person, an obese pubescent girl, stands in the image’s center staring suspiciously at the photographer. She is physically close to the couple but excluded from their intimacy. Her body is obtrusive, making the scene uncomfortable but also a bit funny.

Another photograph shows a bench full of white women taking a break at the 1964 World Fair. Their naked legs are crisscrossed and entangled. Heads, hands, and toes point in all directions, lending the picture a loud and dynamic atmosphere. On their far left sits a black male, engaged in a conversation with one of the women. One can hear the chattering and feel the fidgeting, the excitement of being a part of It. This picture exemplifies one of Winogrand’s talents: He contrasts our expectation (one rests quietly when taking a break, black and white don’t mix) with a piece of New York reality (one never gets to rest).

Many of Winogrand’s pictures include minorities. But his perspective effortlessly swerves far away from stereotypes. People of color appear as a normal crowd crossing the street in front of his car, but also as individuals: Momentously, an African American man locks eyes with a rhino at the zoo. Even when Winogrand gets dangerously close to a stereotype—in the picture that features the hand of a white person handing change to an old black man, for example—he manages to defuse it, by tilting the camera and conjuring up an unexpected tenderness between the two unseen figures.

It should come as no surprise that Winogrand was appalled by the way Magnum photographer Bruce Davidson portrayed African Americans. At a lecture at Rice University he told the students that when Davidson photographed black people, he merely managed to capture the stereotypes whites carry about them. “[In Davidson’s photographs] the black people are about to dance off the pages,” he said. “His work is garbage.”

To find out what things look like photographed also means that Winogrand’s pictures were narratives in their own right, an alternate reality almost. Unlike Diane Arbus, who immersed herself into her subjects’ worlds, Winogrand didn’t get to know the people he photographed. “I don’t know if all the women in the photographs are beautiful,” he said, “but I do know that the women are beautiful in the photographs.” And they are beautiful, even though that’s almost beside the point. Who is making the beauty in the white dress laugh out loud? The only other “person” in the picture is a headless male mannequin in the window behind her.

***

Winogrand never achieved the same recognition as some of his contemporaries in part because he shied away from the big events of his times; there are no marches on Washington or shaggy Woodstock hippies. The familiar makes room for the subtle and mundane human expression. This is why John F. Kennedy finds himself pushed into the background at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, where Winogrand gives center stage to the three excited black women in the front.

To understand what makes Winogrand’s New York, it helps to contrast pictures of his hometown with the ones he took on his trips across America. In 1964, he received the first of three Guggenheim Fellowships. In his application, which details his plan to travel the United States, he said he aimed to “[investigate] photographically … who we are and how we feel, by seeing what we look like as history has been and is happening to us in this world.” (Provocatively, the Met displays a letter by his second wife, Judy Teller, next to his successful Guggenheim application. Lamenting his “grandiose dreams,” Teller wrote, “The time I have to wait while you bumble is nearly exhausted.” The letter includes her wish to have children and her analyst’s bill. Winogrand’s marriage to Teller was later annulled.)

Away from New York, the photographer is not in the midst of the crowd anymore; suddenly we find him cautiously distanced from his subjects. As I examined his New York photos, I asked myself How did he manage to get so close without being punched in the face? In contrast, his pictures of the rest of America made me wonder What kept him so far away?

Winogrand’s disconnect from America is palpable. In the driveway in front of an Albuquerque bungalow stands a diapered child, the only figure in the picture. Behind the boy—or girl, the child seems sexless—mountains ascend, dark clouds loom ominously. Driveway and wasteland separate Winogrand from the child. The three cowboys and three cows in a Texas photograph all face away from the camera. Pictures of cars and shadows of cars, of hotel pools and empty landscapes now dominate the scenery. Irony has turned into sarcasm. In New York, it seems, he had been one of “them,” while in America he became “the other,” the Jew from New York.

In a conversation with Rubinfien in the late 1970s, Winogrand said, “It’s all a matter of how much freedom you can stand.” Judging from the selection in the exhibition, it appears as if the artist was able to stand more freedom in his earlier years than in the last decade of his life. The pictures in the “Bust and Boom” category are bleaker, less ironic. They seem to illustrate their maker’s disenchantment, his search for authenticity gone awry. “Visually simpler than what he produced in the decade just passed, [his late work] generally presents fewer people, less movement, less gesture, and after 1978 or so, tends even to avoid events,” Rubinfien writes in the catalog. He adds that by then Winogrand often didn’t even look at his pictures. The photographs from Los Angeles, he observes, tend to feature “a single distressed, bereft, or inward-looking solitary.”

I’d like to think that it is possible that Winogrand would have overcome this hollow period and found his way back to his pulsating, vibrant New York had cancer not ended his life. The retrospective at the Metropolitan doesn’t deliver a sham conclusion; it documents the struggle as it is.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sabine Heinlein is the author of the IPPY Gold Award-winning narrative nonfiction book Among Murderers: Life After Prison and the ebook The Orphan Zoo: Rise and Fall of the Farm at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. She is a recipient of the Pushcart Prize.

Sabine Heinlein is the author of the IPPY Gold Award-winning narrative nonfiction book Among Murderers: Life After Prison and the ebook The Orphan Zoo: Rise and Fall of the Farm at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. She is a recipient of the Pushcart Prize.