Pieced Together

The Cairo Geniza did more than cast light on Judaism’s literary heritage; it helped us recognize that history’s raw materials can be anything from illuminated manuscripts to bits of junk

Chance encounters on street corners. Secret trips abroad. Whispered hints of buried treasure. To those of us steeped in the writings of John le Carré and Alan Furst, all this smacks of business as usual within the world of espionage. But, as Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole’s new book, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found Worldof the Cairo Geniza, reveals, such goings-on were once as much the province of scholars as spies. In the telling of how, against all odds, a “pestiferous wrack” of papers, as one Cambridge professor put it, became one of the most important finds of the late 19th- and early 20th century, Sacred Trash transforms life within the dusty, dry, and often desiccated groves of academe into something akin to a giant romp, a thrilling adventure yarn—hijinks among the highbrow.

But then, the narrative does something equally valuable as well. In an act of recovery not unlike that associated with the geniza itself, it familiarizes latter-day readers with a host of memorable characters who, regrettably, are not, but should be, household names: Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, the sturdily built Syriac-wielding sisters from Scotland who first alerted Solomon Schechter, the future leader of Conservative Judaism in America, to the geniza’s existence; Francis Jenkinson, the fussy Cambridge librarian equally at home with bird calls and snippets of ancient text; Jefim Hayyim Schirmann, an enigmatic and elusive master of medieval Hebrew poetry who appeared to his Jerusalem colleagues as “the type of character about which novels might be written.”

Sacred Trash—published last month by this magazine’s sister organization, Nextbook Press—has garnered all manner of plaudits, as well it should. My intention here is not to add to them but rather, in the spirit of a pièce d’occasion, to sing the praises of scholarship. By taking its readers behind the scenes and showing how one generation’s garbage turns out to be another’s goldmine, the book underscores what is commonly misunderstood or, worse still, minimized: how scholars come by, make use of, and, above all, expand the definition of what constitutes a source.

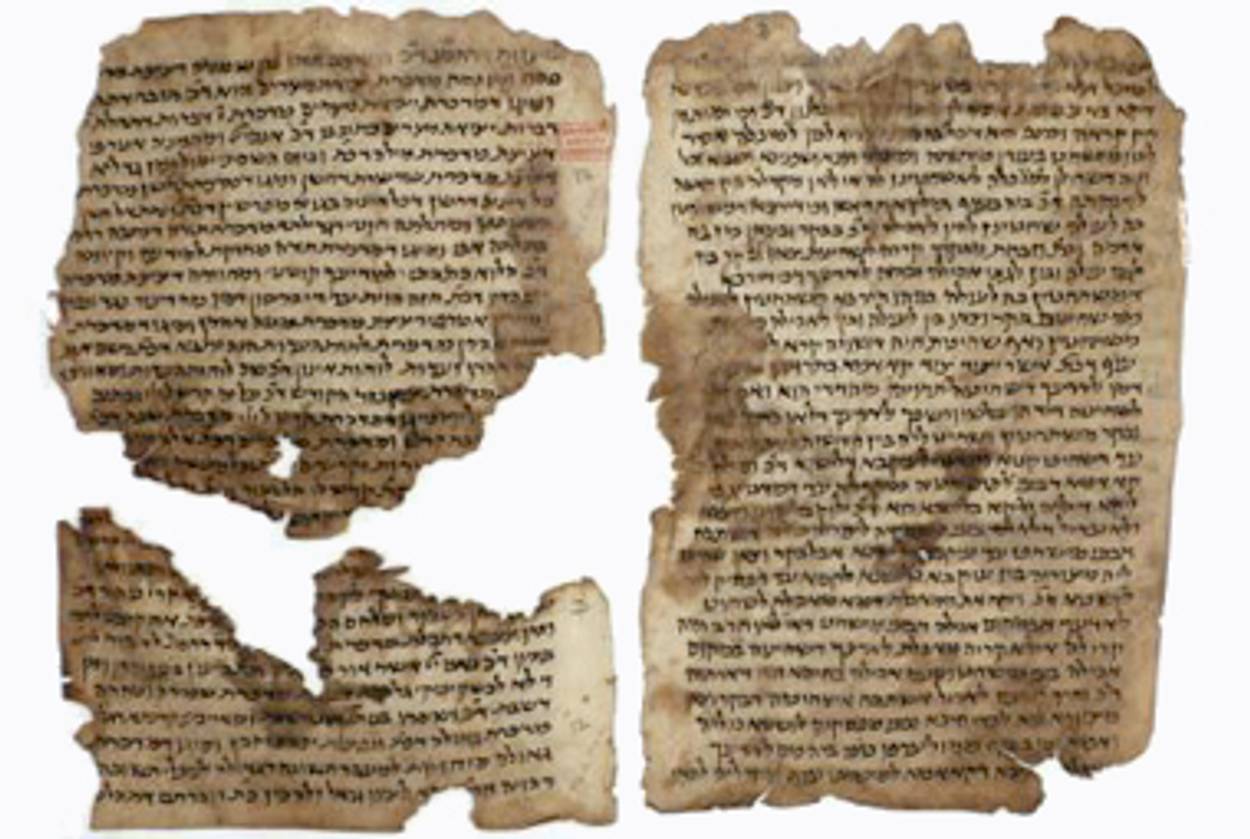

To drive home something of the serendipity that accompanies the scholarly enterprise, Hoffman and Cole quote the good Rev. James Baikie as saying that early Egyptian explorers searched for colossi while their successors contended with crockery. It’s not just that one generation made off with the goodies, leaving the next with the dregs—at least, that’s not how I interpret this passage or, for that matter, the authors’ intent in citing it. It seems to me that they have something else in mind. For they are just as quick to invoke the words of the estimable Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, who, on and off the field, celebrated the vital importance of what he called “unconsidered trifles”: “bits of boxes, string, thread, sandals and … even linen.” Schechter, they tell us in the very next sentence, found in the geniza something quite comparable to Petrie’s quotidian revelations: “textual ‘trifles’ ”—196,000 of them, to be exact.

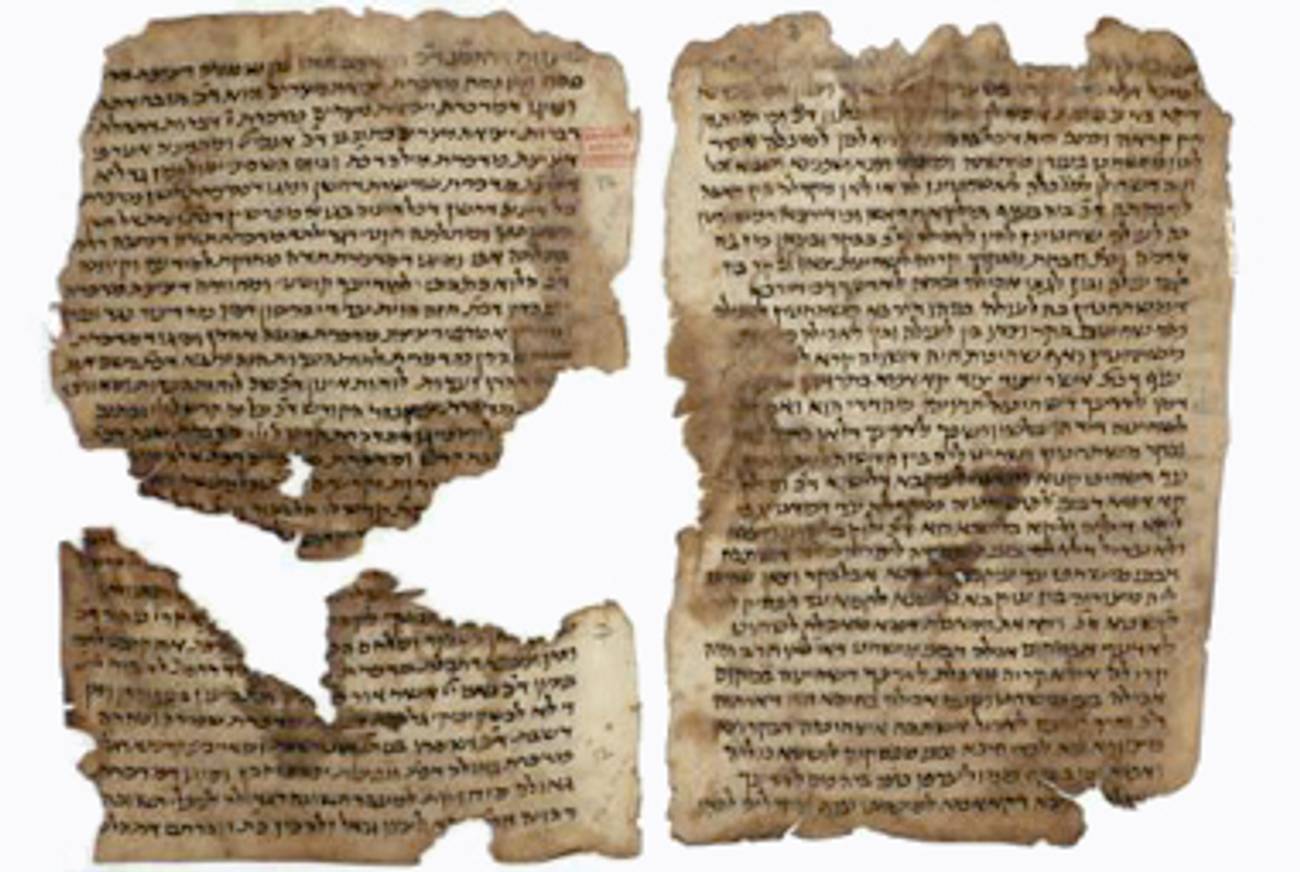

The rest is History. Or, more to the point, as Hoffman and Cole would have us understand, History is the process by which fragments and scraps, the textual and the material, a hint of this and a hint of that, are reconstituted and returned to life by custodians-cum-historians who painstakingly detect, decipher, and distill them, rendering them whole once more.

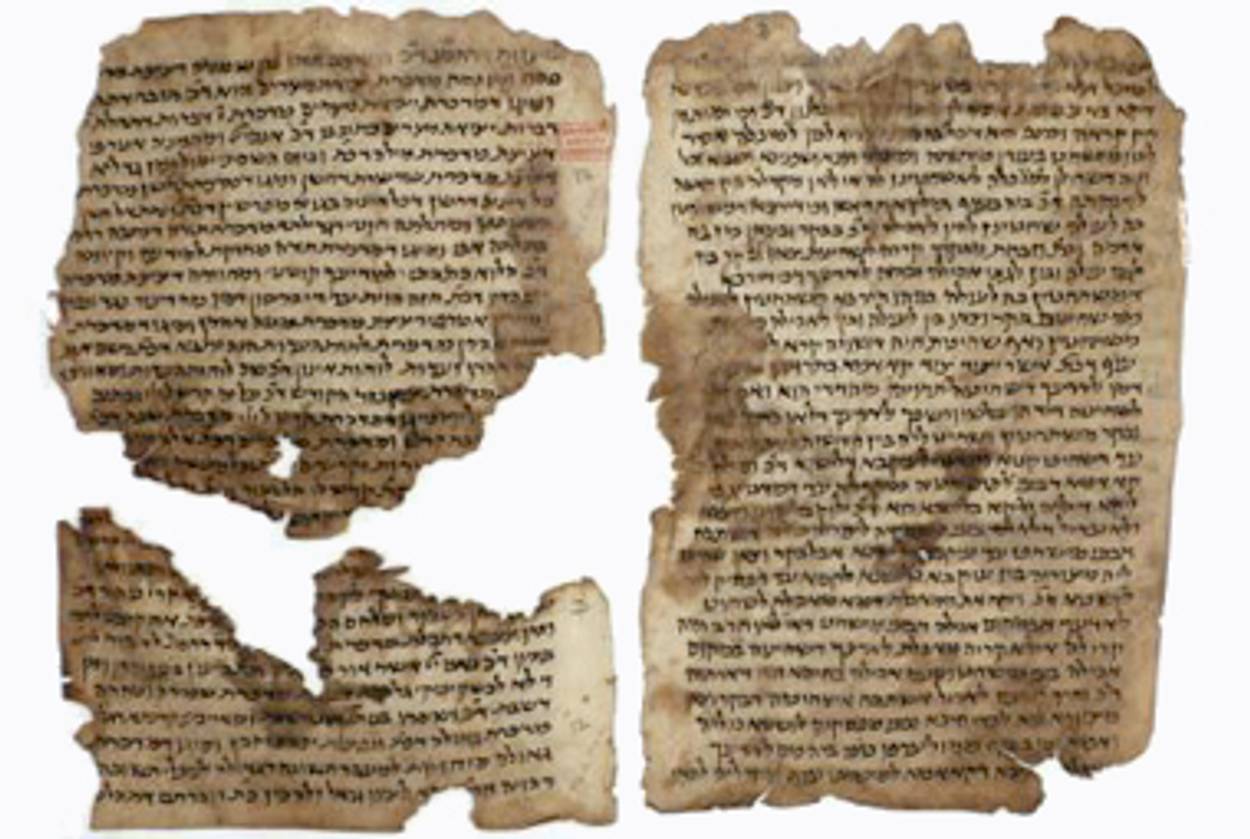

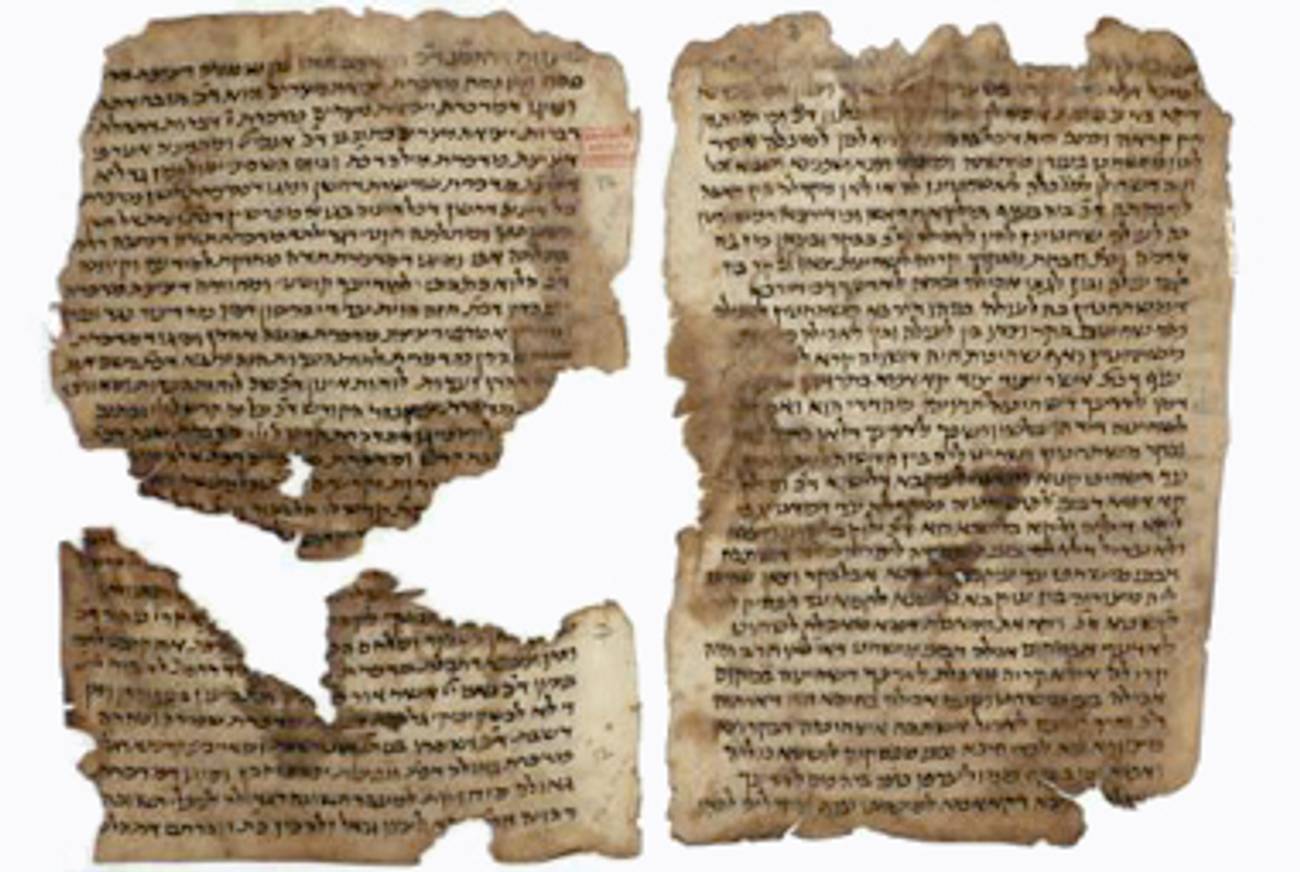

Schechter, to his everlasting credit, recognized that interpretive reality. Whether perched shakily atop a ladder, peering into a room whose every inch was littered with scraps of paper, or covered from tip to toe in what he wittily called genizahschmutz, he discerned something—a vast literary culture—in the jumble of rabbinic responsa, prayers, poems, bills of lading, and bills of divorce that constituted the Egyptian storehouse. Discarded by its owners, mauled by insects, weathered by radical fluctuations in temperature, this stuff was certainly no one’s idea of a bona fide historical source, at least not until Schechter and those scholars who followed in his footsteps convinced the rest of us to take a second look.

S.D. Goitein went even further. Going beyond the literary and the liturgical that fascinated the first generation of geniza scholars, the German-born historian and the author of the magisterial, multivolume A Mediterranean Society, likened the geniza to a “mirror of the world, often cracked and blotchy but very wide in scope and reflecting each and every aspect of the society that originated it.” Drawing on business contracts and legal documents, household records and private correspondence that filled 30 tall crates to the brim, Goitein deepened our perspective, our angle of vision. He made us see that the stuff of history—Jewish history, most especially—comes in all manner of containers: elaborately illuminated manuscripts preserved in their entirety and hastily scribbled “to do” lists; lofty Torah arks and humble calendar art; fine silver and junk.

No matter how grand or how ordinary, each of these items and their like bears a secret, and if we’re lucky, someone will come along—a future historian inspired, say, by Sacred Trash and those who inhabit its pages—and decode it for us. In the meantime, in Old Fustat, Jerusalem, Cambridge, and modern-day Manhattan, history lies in store.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of History at The George Washington University, blogs at www.fromunderthefigtree.com.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.