The Pink Diamond

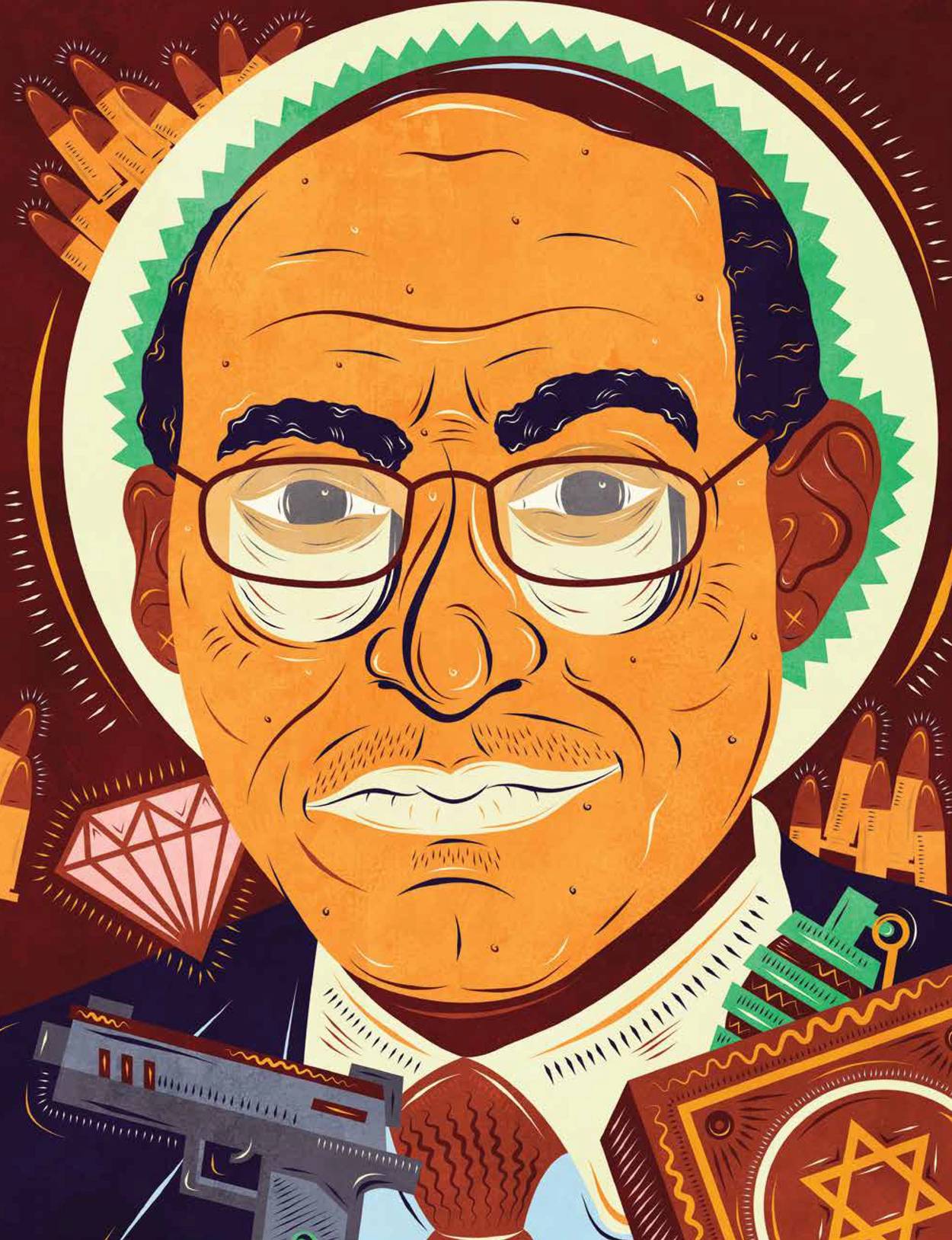

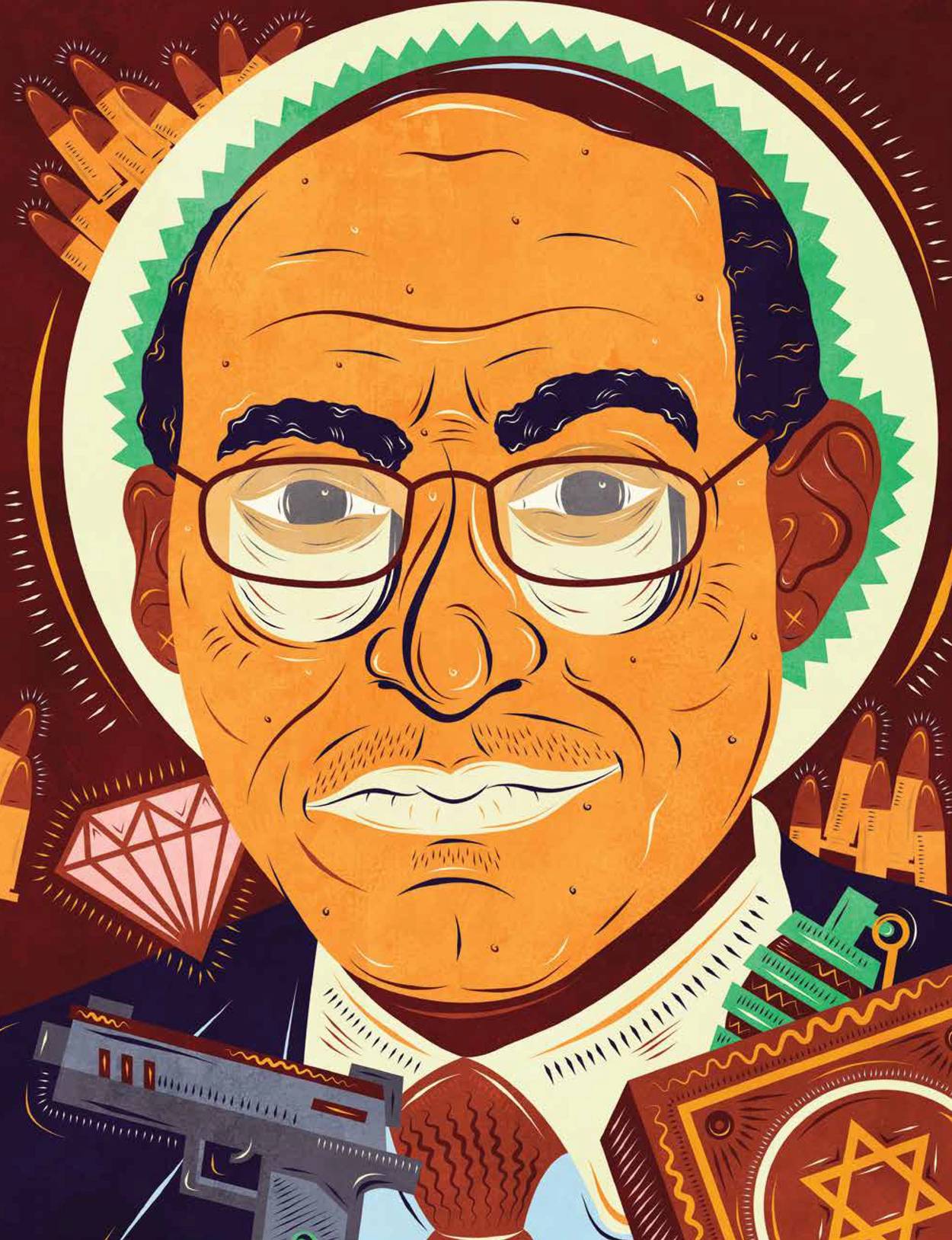

A yeshiva-boy-turned-jeweler from Antwerp becomes Africa’s most notorious weapons dealer

I recently met a Jew at a hotel bar in Brussels to talk about a pink diamond, which had been taken from him several years earlier by the Belgian police. The courts had just decided that the stone is definitely his, which means that it will be returned to him soon, very soon, or maybe it will be returned to his grandchildren. Hotel bars are great places to talk about things like stolen diamonds. The music is just loud enough to encourage conversation while discouraging eavesdroppers—and to make that preference plain, there is usually an extra foot or two between tables, to ensure that everyone minds their own business.

I arrived in Brussels earlier that spring morning, shortly after a round of terror bombings in the unofficial European Union capital. The streets resembled an armed camp, with soldiers in combat gear standing at the main intersections with weapons at the ready. The weather was gray, rainy, and depressing. Even the Belgians on their bicycles looked sick of the place. I think it’s safe to say that neither one of us would have chosen to meet here, or, for that matter, anywhere else in Belgium, if it wasn’t for the fact that the man I was meeting, Serge Muller, was unable to leave the country without the permission of the magistrate who had taken his passport. Denial can be found everywhere in Europe, but there is something particularly rancid about the Belgian variety, where the ghosts of King Leopold II’s victims and the ghosts of the Jewish dead commingle uneasily with the omnipresent smells of kebab and frying oil beneath the starry banner of the European Union—a vast, half-completed bureaucratic project founded on denying the premise that Europe’s past has any necessary connection to its future.

Muller is an arms dealer and onetime African diamond king who earned the title Mr. Blood Diamond after The Washington Post published a story about his activities. As a reporter, I am generally sympathetic to newspapers; but this story, which touched on a world that I know well, ran together various aspects of the African diamond trade to draw conclusions that ran contrary to the facts, which are complicated. Muller doesn’t seem mad about the name: It certainly provided me, and perhaps others, a little thrill to sip cognac with a man known by such a notorious sobriquet.

I first came to know Muller through his son, who wrote me a letter when his father was still imprisoned in Montenegro on an Interpol warrant, for the crime of dealing weapons to the FARC in Colombia in exchange for massive quantities of cocaine—an accusation that Belgian prosecutor Paul Van Tigchelt has pronounced to be ludicrous, though you wouldn’t be wrong to start seeing a pattern here. Muller’s son and I carried on a lively correspondence by post, on the theory that governments are too busy reading emails and texts to bother with steaming open envelopes. While in prison, his son claimed, Serge read an article that I wrote about the Pink Panthers jewel-theft gang. His cellmates, who were involved with the gang, said that the information in the article was good, which made Muller curious, or at least willing to meet me.

Mr. Blood Diamond is looking good for a man who just spent nine months in prison—eight months in Montenegro, and one month in Antwerp. When I compliment him on his appearance, he smiles. I have often thought that there is something especially inhuman about taking a person away from his home and family and locking him up for years at a time in sterile concrete boxes where he is routinely preyed on by other, more vicious criminals; better to whip offenders in public, or chop off their hands. The only reason we don’t understand prisons to be the barbarous form of punishment that they are is that we rarely venture anywhere near such places, in much the same way that we usually manage to avoid contact with death. Closing our eyes to the reality of what it means to send someone to prison divorces us further from the realities of the world we live in, which can come back to us with a shock.

I asked myself, many times, why did Belgium have the merit, and Antwerp in particular, to have a flourishing Jewish community, which contributed to the betterment of everyone?

I mention my distaste for Brussels to my companion, who smiles again, in a more intimate way than before, and takes another sip of his cognac. “I asked myself, many times, why did Belgium have the merit, and Antwerp in particular, to have a flourishing Jewish community, which contributed to the betterment of everyone?” says the diamond king, his cadence swaying with a familiar hint of Talmudic pilpul.

His answer, having grown up in Belgium, and read and thought deeply on the subject, is rooted in the cursed relationship between Europe and the Jews who lived here. In the wake of the Spanish Inquisition, many wealthy Jewish families that had converted to Catholicism transferred their assets to Antwerp, then a Spanish possession and The Wall Street of Europe. From Antwerp, the Spanish Jews could move to Constantinople and enjoy the protection of the sultan.

So, what do we learn from this history? I ask my companion. “I think that in the heavenly accounts and the ledgers, there was some credit,” he explains, “and it had to be settled.” Being Jewish in Europe is not a sociological abstraction or a question of synagogue attendance or metaphysics, he is suggesting. It’s a fate that is written in our bones.

Antwerp was also the port from which survivors of the Holocaust could take the Red Star Line to the United States, I counter. “OK, explain it whichever way, but the question is better,” he says. “The question is a good question.”

Every Jewish family that survived the war was both remarkable and lucky. Born in a small town in Galicia to a Hasidic family, Serge’s father and his siblings wound up in Soviet-occupied Lemberg after the partition of Poland; Serge’s grandmother was killed at the beginning of the war, after she made the mistake of accepting a German offer to return to her village during a lull in the fighting. When the Germans attacked Russia, whoever had money and a place to live stayed in Lemberg; the poor left with the Russians, who resettled them in camps in Siberia, where Serge’s father and his brothers survived the war. At war’s end, Serge’s father made his way to Antwerp, where he had agreed to meet Serge’s grandfather, who survived the war by gaining safe passage to Switzerland.

Serge’s mother, who grew up in a modern Orthodox family in Strasbourg, enjoyed even better luck when the German army invaded; her father, who had been listening to German radio broadcasts with increasing alarm as Hitler rose to power, had already prepared an escape by purchasing false papers and, with the papers, a farm in Southern France. When the Germans came, Serge’s maternal grandfather shut down his factory, and took his family to the farm, where Serge’s mother and her siblings, living under false identities, enjoyed what they remembered as a fairy-tale childhood.

Serge Muller, like every other child in the postwar Jewish community of Antwerp, was a product of his parents’ good fortune. It was a period of great disruption, like during the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, or the pogroms in Ukraine and Russia, when history accelerated, and giant evolutionary leaps were made. “You saw people come back to Antwerp from the camps with nothing, and within one generation, build big families and great wealth,” he says. Survival was not only a source of significant trauma; for those who were young enough, and not too damaged by their experiences, it was proof that anything could happen.

The Antwerp of Muller’s childhood was a place of almost naive optimism, he says, which is a strange way to characterize a community of people who had very recently escaped death. Perhaps the risks of starting a new business with little knowledge of the market and even less capital seemed small when compared to the risk of hiding your children in an attic or a closet to keep them from being put in gas chambers. In any case, no one talked about the war. And because nothing breeds courage and daring like success, those who succeeded then tried their hand at bigger schemes, and began to live out wild fantasies that occurred to them in dreams or simply popped into their heads. Some went into the oil business. The diamond guys from Antwerp who exported stones from the Congo took up waterskiing and skied on the Congo River every morning before shacharit. Henik Applebaum made a fortune flying planeloads of currencies around Africa during the Biafran war, and wound up with exclusive rights to all the diamonds in Ghana.

“Life is dynamic. You have to make it dynamic and keep it dynamic. And as ambiguous as possible,” Muller says when I ask him about the lessons he took from his particular upbringing. “It’s a certain kind of game.”

We have been talking for two hours, and I have a better feel now for the finer subtleties of his attention. As the conversation goes back and forth, I can feel him testing to see how quickly I can switch channels, and monitoring the range of my emotional register in a way that would be familiar to any good politician, reporter, or negotiator, or to couples on dates.

While the Jews endowed Antwerp with a full complement of old-age homes, schools, clubs, and synagogues that made it the envy of the many far less fortunate Jewish communities in Europe, in the same way that the Jews of New York or Chicago were envied, their relationship with the land they inhabited was very different from the one that their American cousins might have recognized. “People wanted not to be Belgians,” Muller explains at one point. It takes me a moment to realize that his locution is deliberate, and not a slightly awkward translation from the French.

Unlike American Jews, whose drive to become “real Americans” was often a multigenerational family drama, and the central focus of novels, politics, and institutional life, the idea of “becoming more Belgian” would have struck the Jews who lived here as absurd. Ruled in succession by Austrians, Spaniards, French, and Dutch, the country or territory of Belgium retained its sense of self as the wealthy polyglot possession of faraway kings well past its formal independence date in 1830. If being Belgian meant anything, it meant making practical accommodations whose desirability was measured by their cash value. Jews were free to walk around in Hasidic garb and talk to each other in Yiddish all day long, as long as they created jobs and spent money. It would surprise no one here in the bar that Serge Muller, dressed in a perfectly tailored suit and discoursing easily about science and philosophy and history and good wine, never thought of himself as Belgian; he was a Jew from Antwerp.

It would also strike no one as particularly surprising that, after graduating from high school, he never applied to university. Instead, he studied for five years at the Ponevezh Yeshiva in Bnei Brak, before spending a year in Lakewood, New Jersey. However, his first exposure to Bnei Brak came as a shock. “It was like everything was in black and white,” he remembers. “There was no color.” Secular books and magazines were banned. He took a mailbox in town, to which his magazines were delivered, and took the bus to Tel Aviv to play tennis and windsurf, returning to the yeshiva with a healthy suntan. The rabbis repeatedly asked him to leave, but in a respectful way, because he was a very good student, and because his father gave money to the yeshiva.

Serge Muller developed his personality by asserting his difference, which was a very Belgian Jewish thing to do—the opposite of trying to assimilate. He wanted to read Nietzsche in Ponevezh, and not choose one over the other. After six years, he chose to decompress from Ponevezh with a year at Lakewood, a more liberal and less rigorous environment where he could openly play tennis and jog. He could also travel to Manhattan, where he enjoyed museums and the symphony and dated American women, including the woman he would marry. After a year of this, he went back to Antwerp to join the family business.

The Mullers were not ordinary diamond dealers. They were De Beers Sightholders, meaning that they were privileged buyers of De Beers diamonds; once a month, a member of the family would travel to London from Antwerp to pick up a preassigned parcel from an agent of the company. The 40 to 50 craftsmen employed in the Mullers’ workshop would then work and polish the diamonds, which the Mullers would sell to the jewelers who came from as far away as Tokyo to buy. Of the approximately 90 to 100 De Beers Sightholders in the world, at least half were located in Antwerp, a distinction that earned the city the title of “diamond capital of the world.”

Anyone with even the slightest understanding of how the diamond business works, or how any business works, could quickly realize that the Jewish diamond dealers of Antwerp controlled exactly nothing. They were middlemen, jumping back and forth between the big Belgian diamond banks, like de Antwepse Diamantbank, which fronted them the money for their monthly purchases, and the De Beers monopoly, headquartered in London, whose South African diamond mines were the richest in the world. The unequal terms of the relationship between the Jewish dealers, most of whom started from nothing after the war, and the De Beers cartel are summed up in the term “Sightholder,” which sounds at first like a title to some form of physical property—perhaps to a “site” where diamonds are mined. What being a De Beers Sightholder actually conveyed was the dealer’s right to purchase a parcel of diamonds selected by De Beers at a price set by the cartel—which the Sightholder was required to pay on sight, and in full, without any recourse to physical inspection or bargaining. To make the one-sided nature of this relationship crystal clear, De Beers reserved the right to cancel the transaction within 48 hours after the Sightholder had paid for his parcel, and take back the diamonds.

What the Jews of Antwerp had to offer the big Belgian banks and the South African mining company wasn’t mining expertise, or capital, or even the ability to cut and polish stones. It was the ability to convey the belief that diamonds were transcendently precious and, therefore, utterly reliable storehouses of value, that made Jews such good salesmen. The value of diamonds rested precisely in the belief that they were valuable—that the sparkle of a tiny stone you could sew into the lining of your jacket or hide inside a false tooth was inherently worth more than a house, or 500 acres of farmland, or someone’s life. Who else could have convinced the entire world of such an absurdity, if not people whose own lives, or the lives of their neighbors, or children, had been saved by such conjuring tricks, which turned a rock into the ultimate signifier of value?

“I remember my father’s gesture when customers would come in, and he would show them diamonds, and they would offer prices that were not good for him,” Muller says, spreading his hands in a way that encompasses some large part of the foolishness that relativistic human minds are prey to. “He would put the box back in the safe, and while putting it back he would say, ‘You can print money as much as you want, but there’s only that much of diamonds. Thank you very much, I’ll keep my diamonds, you keep the money.’”

It took about two years for Muller to learn how to properly polish and value stones, and to acquire the three-dimensional perception that allows a good dealer to zoom inside a stone and examine it from many angles, to gauge what its potential might be, a practice for which the close interrogation of Talmudic arguments can be useful preparation. In 1980, the diamond and precious metals markets—which went up year after year during and after the oil shocks of the early to mid-1970s as buyers sought hedges against the global menace of inflation—collapsed: From a high of $64,000 a carat, the price of diamonds fell to $8,000 a carat, making a mockery of the idea that diamonds were inherently reliable. The collapse shook the De Beers cartel, which continued to charge Sightholders its customary high prices for its diamonds, forcing the dealers of Antwerp to share in the cartel’s losses in order to put a floor beneath the market.

While many Sightholders kept their profits from the diamond bubble and then walked away from the cartel, Muller’s father had a different idea of where the family’s future lay. He took his parcel, and instructed his son to find alternate sources of rough stones at market prices. The profit they would make on those stones would compensate for the losses they would take on the De Beers sight; while profits would be diminished, the volume of the family’s business would grow, increasing their share of Antwerp’s diamond trade. De Beers didn’t mind this kind of activity because it helped bring balance to the market by soaking up some of the excess supply while providing the company with useful market intelligence.

In the diamond district of Antwerp, Muller met and struck a deal with a Lebanese man named Jamil Saïd, who was the marketing agent for the production of mines in Sierra Leone, which were controlled by Joseph Momoh, the country’s president. When Saïd attempted a coup against Momoh, he was thrown out of the country, leaving Muller without a source of rough. So, armed with several years’ worth of invoices, he flew to Freetown, booked a room at the Mammy Yoko Hotel, and gave the hotel manager $200 to arrange a meeting with the president.

“I said, ‘You have diamonds, I am using diamonds. I have the money. Let’s do business straight, cut out the middlemen,’” he recalls of his initial pitch. “He liked this idea very much.” Momoh then referred Muller to his new marketing agent, an Afro-Lebanese man named Mahmoud Kadi.

With Kadi, Muller worked out a deal in which he purchased mining equipment in the West and shipped it to Sierra Leone in exchange for diamonds. In order to make sure that the equipment actually arrived at the mines, he hired a succession of security people, including Dutch, British, and Americans, none of whom worked out. Then, through an old friend in Israel, he made contact with a certain high-level person who helped him set up an arrangement by which veterans of IDF special units who had completed their tours of duty could earn a few thousand dollars a month toward the down payment on a home or business by protecting Muller’s mines.

Life in Sierra Leone early on was pleasant; it was an adventure. It was also quite profitable. He found a nice woman with a big smile named Gloria to be his housekeeper in Freetown, taught her the basics of keeping a kosher kitchen, and later sent her to Antwerp so his wife could teach her how to make gefilte fish and cholent and bake challah.

In addition to a house in Freetown, he had a bungalow at the mining site, which was located near the town of Yengema in the Kono region. The bungalow consisted of a 40-foot-long container with windows cut into the side, and a big water tank on top. In the mornings, sometimes, he would tell one of the workers to fill up the tank, then put on his tallis and tefillin and take a walk into the bush to say shacharit. When he was finished davening, he would take a shower. The mine produced perhaps 10,000 carats of high-quality diamonds a month, which sold for an average of around $300 per carat. The Israeli special forces vets used their skills to set up night ambushes to keep illegal diggers from taking stones.

There were lots of ways to make money off diamonds in Africa. Diamonds and other precious stones can help people move money that might otherwise be difficult to move. Wealthy South Africans, for example, were prohibited from taking money out of the country. On the other hand, it was legal to export diamonds. A man like Serge Muller, who had a license to buy a certain quantity of diamonds, might have someone write him a check, use that money to buy his assigned quantity of diamonds and legally export them, and then return the check to a bank account in Israel or Switzerland, minus 12.5%—a nice built-in profit margin in addition to whatever he might make on the diamonds themselves. Stones of lesser value could also be substituted for stones of greater value, which could then be smuggled out of the country and sold at higher markups. Smuggling diamonds was a well-developed business, with specialists charging 2% to 3% to evade export controls.

For a man like Serge Muller, who grew up in the diamond business, and whose brain had been finely honed by years of study at the Ponevezh Yeshiva, and who came from a community of people who had been brave and nimble enough to cheat death, making money in Africa was child’s play. The challenge was to make a lot of money. He met a guy in South Africa who sold him some very nice, very large diamonds, and whose mining operation turned out to require a significant capital investment. Muller provided the capital and wound up with his own diamond mine, and eventually with a company that was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, which is a fascinating, tangled story of its own.

But the pink diamond didn’t come from South Africa. It came from Sierra Leone.

For a man like Serge Muller, who grew up in the diamond business, and whose brain had been finely honed by years of study at the Ponevezh Yeshiva, and who came from a community of people who had been brave and nimble enough to cheat death, making money in Africa was child’s play.

Like many African leaders, President Joseph Momoh began his service to his nation as a low-ranking army officer—in Momoh’s case, a sergeant. Perhaps because Momoh feared the power of armies to overthrow presidents, or perhaps because he believed that the money could be spent on better things, he kept a few hundred soldiers at an army base in Freetown but refused to buy them ammunition. Instead, he provided them with blanks.

When a small-scale rebellion broke out against Momoh’s rule, led by a local madman named Foday Sankoh, Momoh sent his soldiers off to fight the rebels. One of the soldiers, Capt. Prince Ben-Hirsch, whose father was rumored to have been German, or Jewish, or both, was killed. Ben-Hirsch’s death greatly angered his five close friends in the army, who had grown up together in and around Freetown. What made Ben-Hirsch’s friends especially angry was the fact that they had been forced to defend themselves by shooting blanks. One of Ben-Hirsch’s half-brothers was a politician, and he organized a protest at the State House so that the disgruntled soldiers could demand real ammunition for their weapons.

During the protest, such as it was, a soldier named Charlie Mbayo thumped his grenade launcher on the street, and because there is no such thing as blanks for a grenade launcher, the weapon fired a real grenade, which landed on the State House roof and exploded, sending chunks of masonry tumbling down into the street. Panicked by the explosion and by the sight of armed men below, Joseph Momoh picked up the telephone and called his friend the Guinean ambassador, who arranged for a helicopter to come to Freetown and take the president of Sierra Leone into permanent exile, leaving Ben-Hirsch’s five friends, the oldest of whom was 24, in charge of the country.

“Everybody pointed to the other, ‘You be president, you be president,’” Muller relates. “And for three days, nobody knew who was president. Eventually, they pulled out a guy, a friend of theirs, who wasn’t even part of the demonstration, because he was in the hospital, he had injured a leg or something. His name was Valentine Strasser, and he was a year or two older than the others. And he became president.”

At this point, Serge Muller was the one man in Sierra Leone who had money, good contacts with Europe, access to heavy machinery, a good knowledge of the mining and diamond businesses, and a reputation for fair dealings with the former president. The junta didn’t know Muller, but they knew an Israeli named Zeev (“Zevik”) Morgenstern, who worked for Muller. Morgenstern called Muller, and told him that they now had the entire country on a platter. Muller hopped a borrowed jet into Freetown, where he was met at the airport by soldiers in jeeps, who drove him through the darkened city to his hotel, where he changed clothes. After an hour or two of acclimating himself to what suddenly seemed like another planet, he was taken to the State House to meet President Valentine Strasser for the first time. His first goal was to secure the debts he was owed by the government of Joseph Momoh.

“Everything was dark; there were couple of lamps burning,” he remembers. “There was no air conditioning, so it was hot and humid. And we’re climbing up the stairs, and all the soldiers in camouflage dress, with sunglasses in the dark and in the heat, were walking up with me. They were going to show me Valentine Strasser. There were very few of them. I had the impression of maybe 20 people, some looking out at us from around the corner. They were scared of what could happen.”

The man Muller found sitting behind a big desk in the near-darkness of the State House looked panicked. “He was sitting in the sweltering heat and humidity in a bulletproof jacket, as if someone is going to shoot at him. And he was wearing sunglasses, in the dark,” Muller remembers. “You couldn’t have a conversation with him. It was all cut and broken. The first thing he said was, ‘We need you to help us.’”

Sierra Leone’s new president was willing to entertain the idea of making good on his predecessor’s debts. What he needed in exchange, he explained, were weapons, a trade that Muller knew nothing about. However, back at the hotel, he remembered a conversation he had at the opening of an art gallery in Antwerp with a cigar-smoking banker from Société Générale. The banker had financed a juice factory in Romania that belonged to a Jewish man in Antwerp. The factory produced juice that sold very well. The problem was that he hadn’t found a way to repatriate the profits. It being communist times, the normal mechanism for moving the money was to use the profits from the juice factory to buy something in Romania that could be sold for hard currency in the West. Otherwise, the banker explained, it would be impossible to pay back the loan.

From his hotel room in Freetown, Muller called the Belgian banker and continued the conversation. He raised the possibilities of cement, then rice, and finally, weapons. Did the banker’s Romanian juice factory contacts know anyone at the Ministry of Defense, or in intelligence services, or have any connections to factories that produced weapons? The banker promised to check. Shortly after, he called Muller back with a phone number for the Securitate, Romania’s equivalent of the KGB.

Muller called the number that he was given and explained the situation. He was told that Romania was glad to sell weapons, as long as the proper licenses and end-user certificates were in order. “The next day,” he remembers, “I went back to Strasser, and I said, ‘Look, I need two people that you trust, and that you can vouch for. They are going to be responsible for whatever you buy. Give them the list, I will take them to Romania, they will see the goods, and you will pay me, and I will deliver the goods.’” Strasser immediately agreed, and the diamond dealer, who then knew nothing about the arms trade, was about to become the most notorious weapons dealer in Africa.

When it came time to pick up the cargo, Muller contracted with a Rhodesian pilot named Mike Kruger, who flew a 707 into Bucharest’s main airport in Otopeni, one end of which was reserved for military purposes. The men who met him there were dressed in plain clothes and carried a machine for counting cash. The weapons that they had ordered were packed in wooden crates on trucks, and itemized on a cargo manifest. After the money and the weapons both checked out, the crates were loaded onto the plane, and Muller was ready to leave. “I had brought for myself a sleeping bag,” he recalls. “So I unrolled the sleeping bag on top of boxes there, and we thought we were going to fly out.” A truck then parked in front of the plane. The cost for leaving the airport, Muller was told, was $15,000. Instead of paying, he and the crew emptied a bottle of Chivas and went to sleep. By the morning, the price of departure had come down to $5,000, which he paid.

Landing in Freetown made the risks he had taken seem worthwhile. “Victory!” he recalls, when I ask him to describe the attitude of the soldiers who greeted him and his cargo. “They were driving around the plane in their pickup trucks. After that first delivery, I think that I entered the circle of trust.” After securing their new weapons, the soldiers took Muller to the presidential palace, a huge structure whose imposing terrace overlooked an empty swimming pool. The rooms inside were equally enormous, and lined with beige velour couches. “It was, in their eyes, such a heroic feat that I was able to deliver for the first time real weapons in the middle of a civil war. That’s what they needed, that I instantly became a hero,” he recalls. “And one shipment led to another shipment and then to another shipment.” Muller provided the president and his inner circle with whatever they asked for, like new Mazdas and Toyotas and Jeeps, and became the junta’s trusted interlocutor with the outside world as Foday Sankoh’s rebellion in the bush became a large-scale civil war, with arms flowing freely to both sides.

On one visit, he remembers being taken to the palace to await the president’s arrival. It was a rainy day in West Africa, and as the presidential motorcade climbed up the hill from the State House, he noticed a strange sight: at the front of the procession, a young boy clinging to the roof of a car for dear life, with one hand grasping an antenna and the other hand holding a rag. The window-wipers of the car were broken, someone explained, and replacing them was expensive. It was easier to use the boy.

The horrors of the civil wars that dismantled the flimsy state structures of Central and West Africa in the 1990s were captured in thousands of photographs that appeared intermittently on the front pages of Western newspapers. The most sensational, if hardly the most horrifying, of these photographs featured teenagers dressed in castoff Western T-shirts and recognizable sneaker brands toting automatic rifles that often looked bigger than they were on the ruined streets of African cities. On closer inspection, some of the teenagers appeared to be prepubescent children. The accompanying articles told stomach-turning stories about piles of hacked-off limbs, mass rapes, and armies of child soldiers rampaging through Congo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. In Rwanda, Hutus exterminated the Tutsis, while France, America, and other world powers justified their inaction by banning any official use of the word “genocide.”

Because these events were so horrific, and because the pictures were so striking, and because Africa was generally perceived as being very far away from London or New York, little serious attention was paid to the causes of these awful crimes. Instead, reporters and their editors reached for simple narratives that did not contradict the big-picture stories that readers were being sold. History was at an end. The world was becoming a safer, wealthier place in which states would peacefully dissolve themselves into a new global order of tariff-free commerce and open borders, much like the European Union. A wave of human interconnectedness driven by beneficent technologies would wash away nationalism, tribalism, inequality, bigotry, and other divisive demons, along with the rotting state structures that promoted them.

Trouble spots remained, of course. If it was easy to imagine the kid in a Lakers T-shirt and brand new Nikes brandishing his AK on the streets of Los Angeles during the Rodney King riots, that was precisely the point of the photographs, or, more precisely, of the placement of those photographs on the front pages of Western newspapers. In West Africa, as in South Central LA, the primary cause of such senseless violence must be economic inequality. The suggestion that “blood diamonds” were to blame made sense to everyone from Leonardo DiCaprio to the De Beers cartel and the United Nations. Blaming the wrong kind of diamonds for the carnage in Africa didn’t disturb existing profitable arrangements or trouble anyone’s beliefs about how and why such horrors could still be happening on a newly enlightened planet, where armed conflict and other old-school demons had thankfully been consigned to history’s dustbin.

The deal that Serge Muller struck with Valentine Strasser and his men gave him rights to diamond mines in exchange for the money he was owed. Those rights, which were extremely valuable in theory, soon turned out to be useless, as the expanding civil war made the industrial production and transportation of diamonds impossible. “I think that the last shipment that I actually got out of there was a shipment that was still left over from before the coup,” Muller remembers. Closing down the mines didn’t end the production of diamonds, of course. Using artisanal methods, the diggers continued to work; they sold their production to Lebanese dealers in Freetown, who had previously been shut out of the business. While the underground diamond trade gave everyone involved a greater stake in perpetuating the growing anarchy, the violence had by now taken on a life of its own.

Though his rights in Sierra Leone lay dormant, Muller made plenty of money from his South African mining operations, concentrating on a venture that had the potential to flip the diamond business on its head—a large-scale exploration and mining project in Mauritania, which the geologist Dr. Luc Roumbouts firmly believed could hold the richest untapped reserves of high-quality diamonds in the world. If Dr. Roumbouts’ reading of the magnetic anomalies was right, it was the kind of discovery that happens maybe once in a century—and Muller’s mining company, Rex, would soon control the first legitimate rival to De Beers since the cartel was formed. The historic implications of the find were hardly lost on Muller: The son of a Jewish diamond middleman from Antwerp who had to accept his “sight” on bended knee every month from the cartel would now have the power to affect the market. He would also become one of the richest men in the world.

For a year, the higher levels of the global diamond business could think of nothing else. A representative of a company allied with De Beers tried to buy Rex, but Muller refused to sell. It settled for paying the company $20 million for rights to a not particularly promising plot of Mauritanian land. Rex put the money toward further exploration and testing. Every mining company with spare capital tried to enter Mauritania. But the most likely sites belonged to Rex.

Valentine Strasser’s mental health, which was never good, did not benefit from the copious amounts of palm liquor and local narcotics he consumed daily, or from the pressures of trying to run a collapsing country in the midst of a vicious civil war. After three years, Strasser was replaced by Maada Bio, whose half-brother, Steve Bio, had been educated in Russia, and whose half-sister was the companion of rebel leader Foday Sankoh’s second-in-command. Muller was wary of Bio, but maintained his links with the junta while jetting between Freetown, Antwerp, Johannesburg, and Toronto, where his company was headquartered. “You’re jumping back and forth between different worlds, straddling extremes, at an accelerating pace,” he said. “You can call it a drug.”

Muller embraced the person he was becoming, an international wheeler-dealer who moved diamonds and weapons around the world, while holding the government of a large diamond-producing African country in his hand and controlling Rex, a listed company on the Toronto Stock Exchange that owned the rights to what appeared to be the largest unexploited diamond fields in the world. “People know what you are doing, but they don’t know,” he recalled. “There’s an air of mystery and mystique. You walk down the street and you’re tanned, and they know that you’ve come back. The next morning they’re at your office, and they want to buy the diamonds. It’s exciting.”

The one business that Muller refused to enter at the junta’s behest was providing mercenaries to fight in Sierra Leone’s civil war. Having read Machiavelli’s The Prince, Muller believed that mercenaries would pose an immediate danger to the country, and to his own interests. When Charlie Mbayo pressed him to hire mercenaries, Muller bought a leather-bound edition of The Prince and gave it to Strasser, with a bookmark at the chapter warning against the dangers of mercenaries. Desperate to bolster their own forces, the junta determined to hire Executive Outcomes, a British company run by the South African mercenary Eeben Barlow and his British partners Tony Buckingham and Simon Mann, which would become notorious for its role in Africa’s civil wars. Muller tried to dissuade the junta from this course by taking them to the Half Moon Hotel in Montego Bay, where he had gone with his wife on their honeymoon; he had found that it was easier to persuade the young men of his views when he took them away from their usual surroundings. It would be better to strike a peace deal with the rebels, he explained. Inviting in mercenaries would open up the gates of hell.

Tony Buckingham invited Muller for lunch at Bibendum, the famous restaurant for businessmen in London. Buckingham, who arrived in his Bentley, wore an open-necked shirt unbuttoned to midchest, and spoke in coarse, brutal language, like a nightclub bouncer. Simon Mann was much more polished, and spoke of his acquaintance with the Israeli diplomat David Kimche. “I actually thought at the same time that Simon Mann was potentially much more dangerous than Tony Buckingham,” Muller recalls.

The purpose of the meeting was to reach a modus vivendi by which Executive Outcomes could operate freely in Sierra Leone and Muller could continue to play his role in advising and supplying the junta. Buckingham first asked Muller to waive his rights to buy weapons in Romania. “I said, ‘It’s out of the question. You can buy, and I’ll give them to you at a discounted rate,’” Muller offered. “And then, right away, he had to up the ante. He said, ‘Well, we’ve done our homework on you, and we know where your kids go to school.’ Upon which I got up and I said, ‘Goodbye, fellas.’ I left, and took a cab to the airport.”

With Executive Outcomes now in the picture, Muller’s influence on the junta began to wane. At the behest of an elderly Sierra Leonean diplomat named James Jonah, who served for many years as the country’s ambassador to the United Nations, Muller sought to broker a deal that could lead to elections and stabilize the country. The deal was successful, but the violence continued. A Nigerian peacekeeping force entered the country under the auspices of the United Nations. When the Nigerians required new engines for their helicopters, the U.N. turned to Muller, who determined that the Nigerians needed new helicopters. He purchased the machines under the authority of a letter signed by the secretary general of the U.N. Executive Outcomes saw Muller’s involvement as an attempt to push his way back in. The Washington Post article followed. In response, Muller posted his correspondence with the U.N. Security Council online.

While the controversy died down immediately, the workers in his South African mines went on strike. In both cases, Muller felt the hands of De Beers. “I’ve got somebody from the unions in Kimberley telling me that they were paid by De Beers to strike,” he told me, when I asked him if he had any concrete evidence for his claims. Muller met with Gwede Mantashe, the head of the NUM, the National Union of Mineworkers, who told Muller that the miners wanted half the company. “‘You guys have always been exploiters,’” the union chief told Muller, speaking about the Jews. “‘You’re getting rich on the Black man’s blood.’”

Muller took offense. “I said, ‘Nobody talks to me like that. You don’t like Jews here, but we have invested $20 million in this country.’” If the NUM was so unhappy with his operations, Muller said, he would sell the mines to some Afrikaaners, and they could negotiate a better deal with the new owners. He sold the company, which eventually went out of business. But there was now a target on Muller’s back.

The new government of Sierra Leone, eager for more cash, tried to force Muller to open up the mines, even though the war was still ongoing. When he refused, it canceled his mining rights. The Toronto Stock Exchange, believing that Muller should have disclosed the possible loss of his rights while negotiations with the government were still ongoing, initiated legal proceedings against him; he was barred from serving as an officer of Rex for five years. His stock cratered.

Facing bankruptcy, Serge Muller went back to trading diamonds until he cleared the company’s debts. To his fellow diamond traders, his story was retold as proof of the lengths to which De Beers would go to stamp out competition; the corrupting nature of the African diamond trade; the folly of believing that you can beat the house; and other lessons. No matter which version felt most instructive, it was clear that Muller had fallen from a great height.

It was during this humbling time in his life, as he worked to clear the debt of what was a largely worthless shell company still listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, that Muller was approached by Hans Weber, a Chicago Board of Trade-licensed commodity broker he knew and had previously worked with, about the possibility of acquiring what was potentially one of the world’s largest copper mines. If Muller could persuade the people he knew in the Canadian mining industry to help develop the mine, located in Chile, the broker suggested, the mine owners—friends of the broker’s girlfriend—would vend it into Rex in exchange for equity, breathing value back into the company’s worthless paper.

Naturally, Muller was intrigued by the offer, but also suspicious. “Why me?” he remembers wondering, before he bought his plane ticket to Santiago. After all, Chile is one of the world’s largest producers of copper, and the national mining company is no stranger to the work of developing mines. When he arrived on the site, located on a high plateau in a desert region of the country, he understood why. “There’s no water,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Does anybody here know that there’s no mining without water?’” The Chilean owners didn’t control any of the rights to the land, through which a massive pipeline would have to be built if the copper ore were ever to make its way above the ground. The project was premature, Muller told the disappointed owners. To Muller, it was clear that his life as a mining magnate was over.

By 2001, all that was left of Serge Muller’s legendary operations in Sierra Leone was an office in Freetown and a few kilos of what diamond traders call “black,” or industrial diamonds, which are worth perhaps $1 per carat. The real value of “black” to producers like Muller is to make up weight. “It is useful for substitution,” Muller explained. “Because if you have a mine production of, say, 10,000 carats, and you want to take out some big, expensive stones, you have to replace them in caratage by something that is worthless, in order to fill out the ledgers. So you keep an inventory of black-coated diamonds at the bottom of your drawer”—i.e., junk, a supply of which might prove invaluable when a producer needed to substitute something for the weight of an 80-carat stone.

After selling the smaller stones to Indian dealers at $1 or $2 per carat, Muller was left with a shoebox full of larger stones—anything over 20 carats. “That you keep,” Muller explained of the larger stones, “because if you have a stone that is very large, it could have a skin, and inside it could be good.” While it is extremely unlikely that stones that are initially categorized as industrial diamonds turn out to be anything more valuable, it can happen—the same way that, every 10 years, someone might find an Old Master painting at a yard sale.

Still, picking through his shoebox of black in search of an overlooked gem seemed like as good a way as any to pass the time. Joining him in the office one day, his friend Bruno, who sold high-end watches and antique cars to the diamond men, asked to share in the fun, and picked up one of the biggest stones in the box—perhaps 60 carats. “He says, ‘I want to buy that one,’” Muller remembers. “I said, ‘I’m not selling. I’m looking here at the good stuff, for me.’”

Alive to his friend’s intuition, Muller took the stone to a local polisher, who could open windows into the interior of the dark crystal. “We look inside and saw: ‘Wow. There’s something in there.’ A big shine,” Muller recalls. The mine that produced that particular piece of black-coated diamond had also produced some pink diamonds of extraordinary quality, he knew. This stone was bigger. He told his friend who first spotted the stone that he would let him be the agent for the sale. If they were lucky, he might collect a commission on an enormous pink diamond worth $10 million or more.

Plenty of things could go wrong before that day came, though. The black “skin” (or “peel”) of the stone would have to be removed very carefully, because every carat that was lost could represent a lot of money. If it was indeed a very large diamond of gemlike quality, the majority of its value would still reside in the pink color that Muller had glimpsed through the window. Yet the color could turn out to be variable rather than evenly spread throughout the stone. In addition to negotiating clarity and size, whoever cut and polished the stone would also have to be conscious of the effect of his or her choices on how the stone’s color appeared from multiple angles, which made the job exponentially harder. Cut the stone in the wrong way and you could lose the greater part of its potential value.

Muller took the stone to a specialist named Matis Witriol on 47th Street in the Diamond District in Manhattan, who spent six months of painstaking work exploring and shaping the stone. When he was done, Muller shipped the main diamond along with several accompanying smaller stones to Israel to have them finished. The result was a 10-plus-carat pink diamond of extraordinarily high quality, certified by the Gemological Institute of America. Now finished with Belgium, Muller had moved his family to Israel and was waiting for his youngest daughter to finish high school before making aliyah. He gave the stone to his friend, who put it in his safe and set off on a sales trip to Hong Kong.

Late one evening in 2008, waiting around his empty house in Antwerp, Muller got a phone call from Bruno’s wife, Marjorie. The police were in her house, she said, and they had found and sealed her husband’s safe. Muller knew that whatever was going on was serious. He also knew that his stone was in his friend’s safe. “I said, ‘You know what? First of all, your husband shouldn’t come to Belgium, he’s going to be arrested at the airport. He should fly to Amsterdam,” Muller recalls. The basis for the police warrant was an allegation that Bruno had sold an expensive car to a port official who had close ties to a local cocaine ring that was importing the drug into Belgium.

Muller drove to Amsterdam with Marjorie to pick up Bruno at the airport. His friend assured him that he had nothing to do with the coke ring, and he promised to make sure that the stone was safe. “He never lied to me,” Muller said. “He’s a streetwise kind of guy, but with the code of the street, you know? ‘OK,’ I said, ‘get yourself a good lawyer because I want that stone released as soon as possible.’” The police opened the safe and had a specialist from a lab provide a certificate that the stone they took from Bruno’s safe matched the particulars of the stone that had been certified by the GIA. In November 2014, after nearly six years of investigation, the court in Antwerp ruled that Bruno in fact had no association with the coke ring, and that the stone that had been seized from his safe was Muller’s property.

The Diamond King’s new business, which he was running from Israel, was beginning to prosper. Acting as a senior adviser and consultant to Israeli-based defense companies, he got back into the arms trade, providing European weapons with Israeli upgrades to the governments of African countries, including South Africa, Kenya, Zambia, and Djibouti. Certain companies also acted as a pipeline for Israeli special forces veterans who did security and logistics work. One major client for these services in Africa was the United Nations.

When Montenegro Defence Industry, a recently privatized defense company, was put up for sale, two companies that Muller had consulted for, including a company called ATL, placed the winning bid. Muller and his associates flew to Podgorica in March of 2015 to sign the papers. Muller was eager to get home: The next day was Purim. The meeting was supposed to be at 11 o’clock in the morning, but was postponed until after lunch, meaning that he would miss his return flight. Luckily, a travel agent found him a flight from Tirana through Istanbul.

What happened next was entirely unexpected, Muller says. And having listened to his story for the past six hours, I am only a hair shy of understanding why. “I get to the border, and I show my passport, and they say, ‘Well, there’s a red notice, an Interpol notice on you,’” he recalls. “And everybody looks at me and they say, ‘What?’ Now, we supply the police of Montenegro with their weapons. They all know us. They have to arrest me? So they apologized.” The police took Muller to national police headquarters in Podgorica with a promise to see what they could do.

The Montenegro police chief invited Muller into his office. “Stay here, make all the calls you need,” he said, “but get ready for it because this is going to be a bad one.” The idea that De Beers reached its long arm into the Balkans to seek some sort of revenge was clearly absurd. Of course, he still had plenty of enemies left. There were the other bidders for MDI, for example. Perhaps one of them had used his local clout to trip Muller up.

The next day, Muller was brought in front of a local judge, and the Interpol warrant was read aloud: He was accused of selling weapons to the FARC, the Colombian leftist rebels, during his trip to Santiago, and of having been paid for the weapons in cocaine, which he laundered through his Belgian real estate companies. He had then used the proceeds to build a yacht. Muller did own a yacht in Greece, but the rest of the warrant was clearly a tissue of fantasies and lies. He had done plenty of things in his life, but he had never dealt in cocaine; he never sold weapons to the FARC, and he never laundered drug money, through real estate companies or in any other fashion.

His head spinning, Muller consulted his lawyer, who told him he had two options: to agree to be extradited to Belgium on these charges, which he could then quickly answer in court—but which could be seen as an admission that the warrant had some conceivable basis in reality, and which could also land him in the hands of his enemies, whom he couldn’t yet see or identify, but who clearly had pull with the Belgian police. Or he could refuse the charges and fight extradition, in which case he could wind up spending the next eight months in a Montenegrin jail, before being remanded to Belgium. The choice before him was clear.

“Very quickly I realized, more important than anything here is my name,” Muller recalled mournfully over the remains of a delicious dark-chocolate mousse. “I will never do any defense deal again if I accept these charges. I said, ‘I refuse these charges. They are lies.’” As his lawyer predicted, he then spent the next eight months in jail.

“The first night, I remembered the book that I read in Ponevezh by a French psychiatrist, Franz Fanon—Les Damnés de la Terre, The Wretched of the Earth,” he says. “That came back to me right away. And I said, you know what? I will banish from my heart frustration and hate and any negative feeling, because that is going to scar me. I will be only positive. That’s it. There’s no room for ‘I hate this guy, I hate that,’ revenge, all of that. Nothing. This is my destiny, I have to live with it, and I will make the best of it.”

Muller never saw the judge again. Still, Muller had powerful friends in Montenegro, and the court seemed to recognize that while anything was possible, the charges contained in the Interpol warrant seemed absurd. Why would a diamond dealer be trading in coke? Why would a man with a thriving weapons business in Africa—and now in the Balkans—be selling weapons to South American rebels?

Over the next eight months, the Belgian prosecutor’s office failed to provide any evidence to substantiate the warrant. At the very last moment of the maximum period that Muller could be held in Montenegro, it dropped the weapons and drug charges, and asked that Muller be extradited on a money-laundering charge that had already been thrown out of court.

During his time in prison, Muller had no shortage of time to think about his case. “I said, ‘You know what? It’s not coincidental that they opened up the file one month after they had to return the stone to me. Maybe that stone was swapped.’” His entire ordeal, he came to believe, might have been the result not of his own activities in Africa or the Balkans, but of something else entirely: an attempt by the Antwerp police to cover up the theft of his rare pink diamond.

When Muller arrived in Belgium, he asked for the stone to be reevaluated. The judge refused, and then refused again, and refused a third time. Finally, the judge went on vacation. “The replacement said, ‘OK, go ahead,’” Muller recalls. By the time the original judge returned to his position, it was too late to vacate the order.

The Belgian diamond police, Muller’s lawyer, Bruno, and a representative of the court equipped with a diamond tester went into a safe room to test the stone. “He brings a testing machine with the lawyers and the police and everybody’s witnesses, and they test the seized diamond jewelry of Bruno’s wife, and the machine shows diamonds. He puts it on that stone, and it shows fake.” It may or may not be coincidental that when the head of the Belgian diamond bureau was recently arrested on corruption charges, the police found diamonds in his house, and money.

“So what’s happening with the diamond now?” I ask him.

“A judge has been appointed. They always try to buy time, try to stretch it as long as possible. But it’s OK, we have time, we have time,” Muller sighs. It’s impossible to say where the real diamond went. As I stand up to stretch my legs, in preparation for a long, uncomfortable flight to Kyiv, I realize that I have one more question to ask him.

“Did you ever give the stone a name?” I wonder.

“No,” he answers. But he realizes a moment later that his answer isn’t strictly true. “I did,” he admits. “A guy who writes the diamond newsletter in Israel came to visit me and I told him, ‘You know, this is probably the last blood diamond. And probably the only real blood diamond there ever was.’”

“Why?” I ask him. A half-smile plays around his lips. We are two Jews sitting together at a hotel bar in Europe, which means that no matter how unlikely or incredible the story, the punchline is always the same.

“Because they drank my blood,” he answers.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.