“Here lies the body of Jonathan Swift, where savage indignation can no longer lacerate his heart.” This epigraph, written by the great satirist for his tombstone, is a reminder that the live wire of outrage snaked through his best, most entertaining, work. Perhaps the lack of this sort of animating passion is one reason why two new books that take aim at Jewish conspiracy theories— Joshua Neuman and David Deutsch’s The Big Book of Jewish Conspiracies and Will Eisner‘s The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion—are neither fun nor transformative.

It’s not that these authors don’t mean to challenge or provoke readers. In the case of Eisner—the pioneering cartoonist who completed The Plot a month before his death in January at 87—the urge to fight hatred was strong from the start. Raised in New York City during the 1930s, he was shaped by the era’s radical politics, rampant anti-Semitism, and vogue for literary realism. While other artists created fantastical crime fighters with otherworldly powers, Eisner made his mark with The Spirit, a colorful but ordinary masked man (Eisner called him a “middle-class superhero”) who is not above the fray and tensions of everyday life. So it’s not entirely surprising that Eisner hoped The Plot would “drive yet another nail into the coffin of this terrifying vampire-like fraud,” as he explains soberly in the preface.

For their part, Neuman and Deutsch, co-editors of Heeb, obediently state their satiric intentions in The Big Book‘s introduction—one practically senses the nervous figures of the publisher’s legal team hovering just above—but otherwise avoid staking out any position that might infringe on their fun. Instead, they recycle Borscht Belt jokes and half-baked plotlines to concoct explanations for two millennia worth of conspiracy theories. Thus we get the conspiracy behind the Exodus story in “Let My People Go…On Longer Lunch Breaks,” while “Blood Brothers” depicts the baking accident behind the medieval blood libel. Like many gimmick books or Saturday Night Live spinoffs, The Big Book is long on clever concepts but short on execution. Much funnier are some of the Photoshop illustrations; one puts a pair of Groucho Marx glasses on the grotesque Jewish serpent from the English edition cover of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, purportedly the logo for a motorcycle gang.

That The Big Book‘s illustrations stand out above the text makes a lot of sense. Ever since its launch in 2002, Heeb‘s mix of lefty politics, hip-hop language, and DIY Judaism has found its most effective form in the magazine’s visual presentation. (I was a Heeb editor for two years.) The debut issue’s cover featured a round matzoh resting on a turntable, with a bejeweled black hand hovering over it. Whether or not such imagery actually evokes the sensibilities of more than a fraction of hipsters is beside the point. The photo hints at longstanding flashpoints—black-Jewish relations, money, Jewish ritual—even as it perfectly encapsulates the magazine’s madcap irreverence.

Meanwhile, The Plot charts the secret history behind the most infamous Jewish conspiracy of modern times. It begins in 1864, when a French pamphleteer named Maurice Joly attacked the reign of Napoleon III in a satire called A Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu. The book languished in obscurity until 1894, when Mathieu Golovinski, a talented forger for the Russian secret police, rediscovered it. While liberally plagiarizing whole passages, Golovinski altered the earlier work just enough to recast it as a master plan for Jewish world supremacy.

One of Eisner’s most enlightening—and tedious—devices is a side-by-side comparison of the Russian and French texts. In one bizarre twist, Golovinski’s “Jewish” plot includes a bizarre homage to the Hindu god Vishnu. Of course, the point here is that if we understand history, we won’t be condemned to repeat it. Sadly, this has been disproved again and again; Eisner himself observes that in 2002 Egyptian state television sponsored a series based on The Protocols.

In the amusing caricatures of Russian apparatchiks, there are flashes of the quiet impishness that marks Eisner’s vintage work. But the lack of more humorous touches in The Plot, along with the absence of any psychological nuance (as compared with, for example, the four stories in A Contract With God), suggests that Eisner was simply too driven by his agenda to be inspired. Rather, in his quest to pull back the curtain on a century’s worth of nefarious obfuscation, he creates an earnest, convoluted story that, for long stretches, drags.

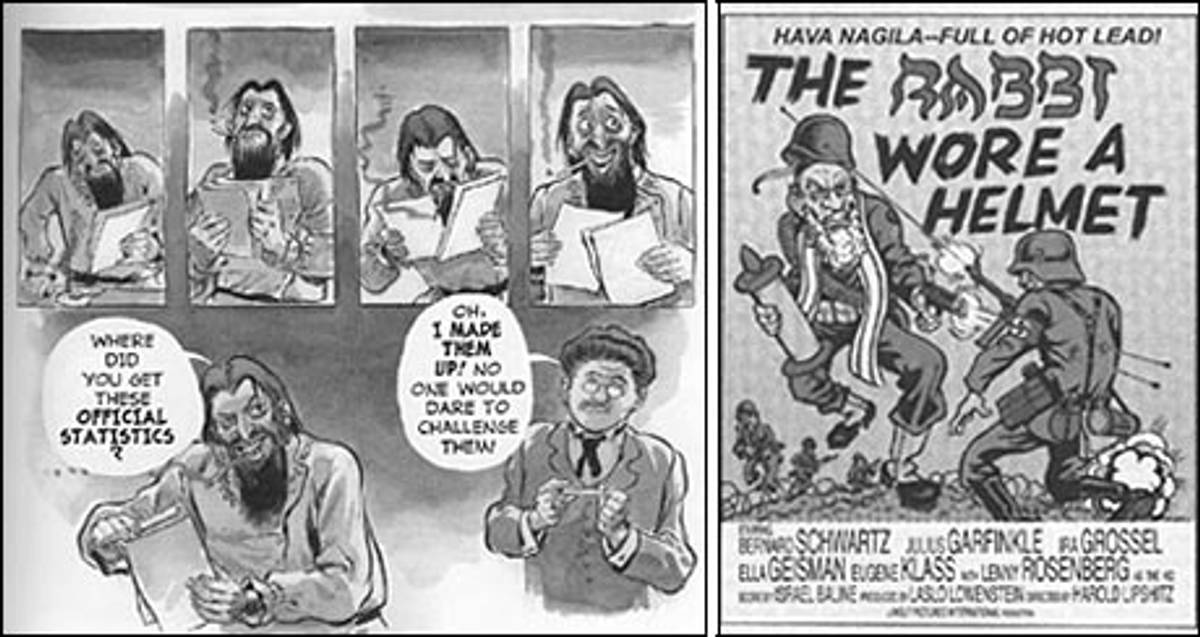

Left: A Russian editor conspires with Mathieu Golovinski in The Plot; Right: An imagined World War II movie poster from The Big Book of Jewish Conspiracies

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, purported to be notes stolen from the 1897 Zionist Congress, still manages to sway the naïve as well as the malicious. That fact alone sparks the sort of savage indignation which, effectively channeled, might have lifted The Big Book and The Plot beyond the pedestrian. Either way, the comparison to Swift is instructive. To the unsophisticated reader, the Protocols‘ phony backstory functions a lot like the “mask” in the satirist’s greatest works. After years of being unable to convince his fellow countrymen to be more responsible for their own welfare—Irish landlords were practically cannibalizing their own kind with their exorbitant rents—Swift stumbled upon a brilliantly simple solution: Assuming the mien of a perfectly reasonable gentleman, he outlined a ghoulish recipe for eating Irish babies.

Golovinski’s pretense of stolen notes only reinforced vicious stereotypes, while Swift’s clever mimicry eventually led the intelligent reader toward some larger truth. It’s hard to imagine how “A Modest Proposal” would go over today. We live in an irony-drenched culture, yet are so fearful about giving offense that we avoid genuine satire, as The Big Book‘s introduction makes clear. Yet it’s useful to consider whether the clarifying force of Swiftian logic—rather than earnest entreaty or slapstick irony—may just be what we need to keep vampiric Jewish conspiracies from rising again.