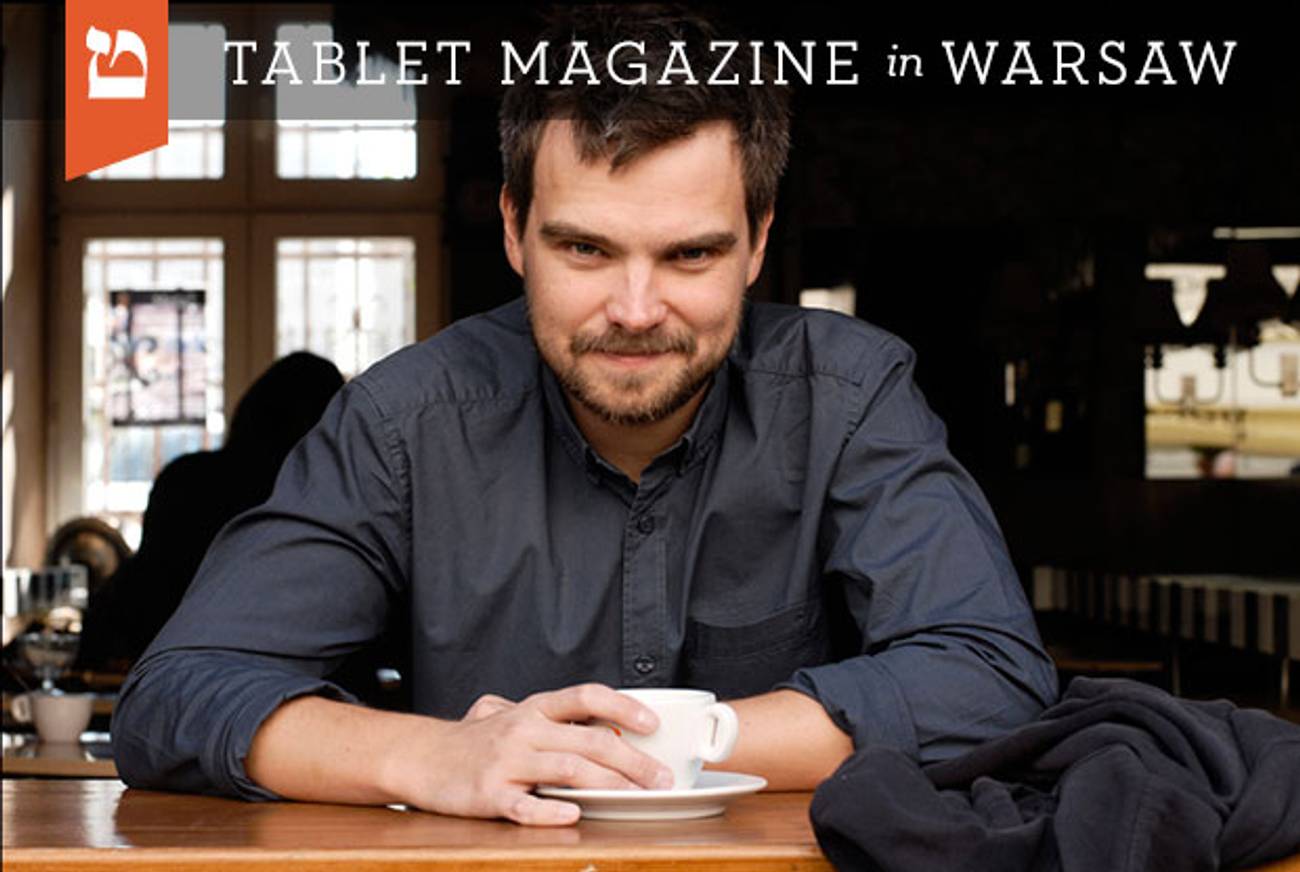

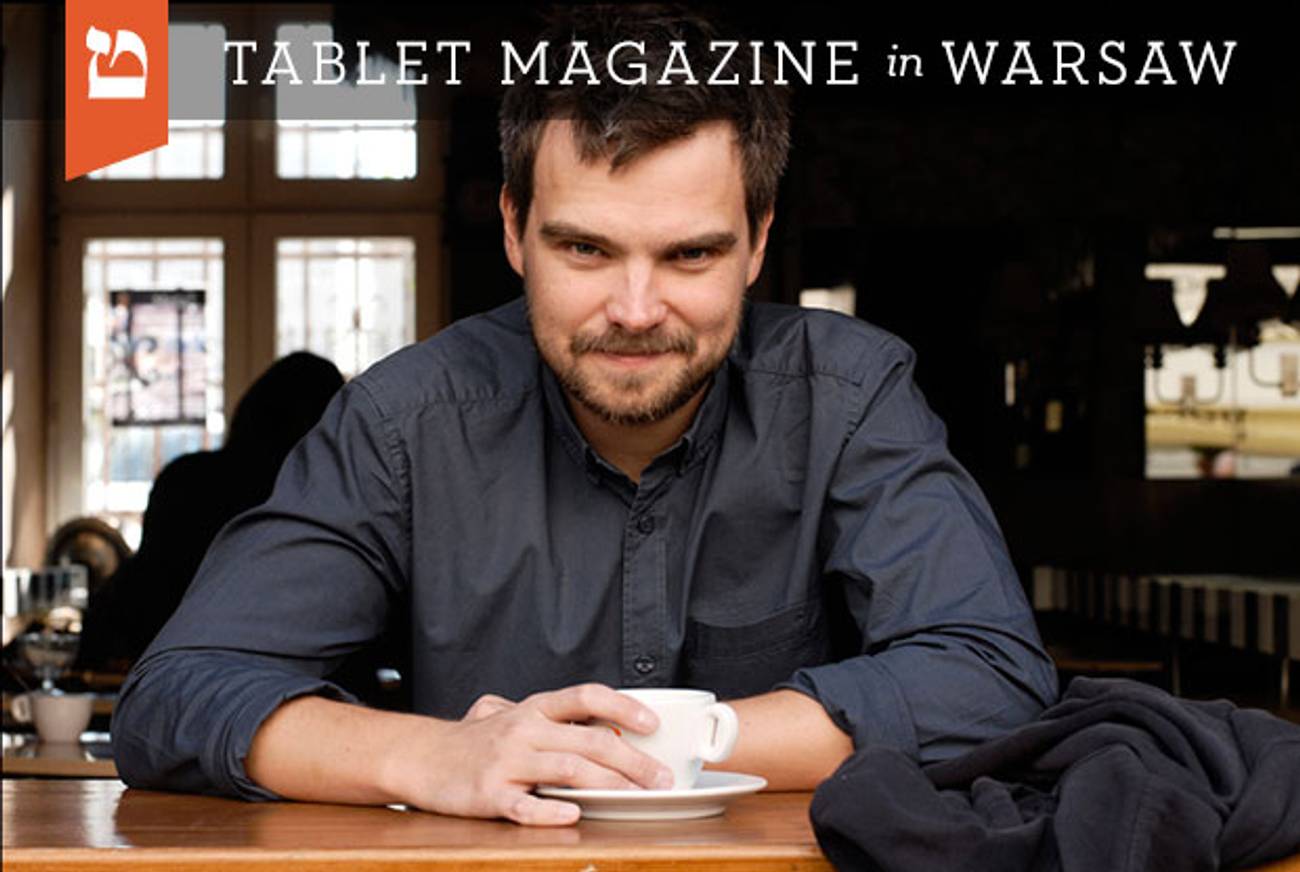

Poland’s History Detective

Zygmunt Miłoszewski plumbs the country’s painful past in his best-selling thrillers

To know a place, look at its detectives: San Francisco’s lust and greed have hardened Sam Spade into a diamond, and the soggy streets of late-Empire London have made a drug-addled maniac of Sherlock Holmes. Kurt Wallander is as gloomy and given to existential terrors as the Swedish countryside he so ably polices, and Paris, c’est Commissaire Maigret. Now Warsaw, too, has its hard-boiled emblem in prosecutor Teo Szacki, a human seismograph ably recording all of Poland’s historical tremors. The crimes he must solve, then, are shrouded not only in mystery but in eight decades of tension and trauma, from anti-Semitism to post-communist malaise.

Szacki’s creator, Zygmunt Miłoszewski, a former editor of the Polish edition of Newsweek, is feeling the burden of history as acutely as his world-weary character. Even though he insists that a thriller’s sole purpose is to make the reader eager to turn the page, he chose to submerge his hero not only in Poland’s seamy underside but in its painful past as well. His first novel in the Szacki series, Entanglement, published in Poland in 2007 and translated into English in 2010, is rich with plotlines involving the largely unprosecuted and immensely powerful cadre of former Communist operatives, the ruthless men who transitioned neatly from secret policemen to secretive financial tycoons. When the book came out, Miłoszewski found himself in the strange position of being praised by some unlikely admirers.

“For a while,” he said, “I was the favorite writer of the nationalist, anti-Semitic right-wing,” for whom the fact that so many of the Communists’ crimes have gone unpunished serves as proof of a conspiracy between the ancien régime and its eventual inheritors, Lech Wałęsa and his fellow members of Solidarity. As absurd as the claim may be, it is rooted enough in the contemporary Polish psyche as political shorthand; few on the left, Miłoszewski said, including many of his fellow journalists, cared to review any novel, even a detective story, that explored the murky world of the Communists in any way.

This pleased Miłoszewski. His mission, he said over pierogis in a popular Warsaw café earlier this week, was “to punch the happy, smiling Polish face, so proud of its history. That’s what artists should do. If you want to be proud of your nation’s history, you must be ashamed of what was wrong.”

With Entanglement selling briskly, Miłoszewski went in search of something else that was wrong with Polish history. Naturally, he thought of the Jews. Thus was born A Grain of Truth, published in 2011 and an instant best-seller. As the novel begins, Szacki, having destroyed his marriage and sabotaged his career, moves to a small town in the south of Poland in search of an idyllic life of quiet streets and green fields and little malice. The corpses, however, soon start popping up. To make things worse, the murders all seem to be recreations of ancient blood libels: Some turn up next to kosher butchery knives, others in nail-spiked barrels, the alleged method by which Jews had drained the blood of innocent Christian children. The local church also happens to feature an 18th-century painting portraying murderous Jews and martyred toddlers, which makes everyone in town suspect that the killings are either the work of Jews taking vengeance for the persecution and pogroms they’ve experienced from their Polish neighbors or of anti-Semites trying to frame the Jews in a particularly gruesome way. Szacki, however, knows better. He suspects that the murders’ ritual nature is just a smoke screen. To get to the truth, he must wrestle his way through history.

That, said Miłoszewski, is not only the detective’s work, but also the writer’s. Before the war, he said, “the truth was in everyday life. There were prejudices, there were even hatreds, but Jews and non-Jews were neighbors. Then, suddenly, daily life disappeared, and all that was left were the prejudices. And now, the truth is that people don’t have enough knowledge.”

In addition to being a first-rate mystery with a complicated protagonist and enough mood to paint even the brightest day noir, A Grain of Truth is also, at least in part, interested in knowledge. Among its characters is a young and charismatic rabbi, and the plot is propelled forward not only by masterful storytelling but also by a sense of what is gone and will never be back. “There’s a huge difference between being sorry for the victims of the Holocaust and the feeling of loss to the city, to the fabric of being,” Miłoszewski said. “There used to be a Jewish district here, Jewish restaurants, Jewish mobsters, Jewish stores. They’re all gone. All this daily life is gone.”

And there’s no better champion of all that was lost than Szacki. He made his man a prosecutor, Miłoszewski said, in order to plant him firmly in very rigid ideological ground. “A prosecutor is more complex than just a cop,” Miłoszewski said. “A cop is always gray—on the good side, but must deal with the bad guys, so the line is very thin. A prosecutor is closer to the judge than he is to the police. All he wants is justice. He doesn’t do deals.” Such moral absolutism is Szacki’s greatest tool; unfazed by the sound and the fury around him, he doggedly does his work and ignores all distractions, from office politics to an unkind press corps. When a reporter asks him if he is an anti-Semite, for example, in an attempt to get him to lose his cool, Szacki hisses back, “If you’re a Jew, then yes.” Sam Spade couldn’t have said it better himself.

***

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.