One of the most unusual features of Timothy Snyder’s Black Earth, writes Christopher R. Browning in his New York Review of Books review, is the many pages Snyder devotes to Poland, Zionism, and Palestine. At the center of this story is the short-lived alliance between the Polish government and the Zionist Revisionist Movement during the late 1930s, explored in the book’s first four chapters (the third titled “The Promise of Palestine”) and revisited in the conclusion. After Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s death, the ruling circles in Poland advocated solving the country’s so-called Jewish problem through the emigration of 90 percent of the Jewish population (estimated at about 3 million on the eve of the war). For that purpose, Snyder recounts, the Polish government lent public support to Revisionist Zionist leaders and paramilitary groups and even financed and trained them. Their hope was that these Jews would wage a campaign of resistance and terror against the British mandatory authorities in Palestine and establish a Jewish state open to large-scale Jewish emigration.

Why is the history of Revisionist Zionism and their Polish supporters so central to a book that claims we have misunderstood the Holocaust and purports to offer a new explanation for it? The Polish-Zionist Revisionist alliance is in fact so central to Snyder’s account that the four main Zionist Revisionist protagonists in his story—Vladimir Jabotinsky, Avraham Stern, Yitzhak Shamir, and Menachem Begin—are mentioned in the book more often than Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill combined.

One place to start is by situating Snyder’s discussion of Revisionist Zionism within its context in the book, namely an alliance that never materialized between Germany and Poland. As Snyder tells us, Adolf Hitler had initially hoped to draw Poland into a joint war of aggression against the Soviet Union. After some negotiations, Polish leaders rejected Hitler’s overtures. They determined that maintaining the status quo in Europe would benefit Poland more than war and feared that they would become a German satellite state following the Soviet Union’s defeat. Snyder, however, proposes that Hitler’s dream of a Polish-German alliance failed not merely because of Poland’s political calculations but ultimately because of ideological divisions. The failure to reach an agreement and the ensuing German invasion of Poland, he writes, “resulted from deep differences on the Jewish and Soviet questions that were shrouded for years by Polish diplomacy.” Snyder sums up these differences two pages later: “The covert essence of German foreign policy in the late 1930s was the ambition to build a vast racial empire in eastern Europe; the covert essence of Polish foreign policy was to create a State of Israel in Palestine from the territories granted by the League of Nations mandate to the British Empire.”

It was worth pausing to consider this very large claim. Snyder argues that in the late 1930s the Polish government considered the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine as a major foreign policy goal, the “essence” of its foreign policy—a claim he makes in part in order to emphasize the differences between Nazi and Polish anti-Jewish attitudes. While the Nazis sought to eliminate the Jews from their future racial empire, the Poles wanted to create a state for them in Palestine. The Polish-Zionist Revisionist alliance is explored throughout the book to demonstrate the extent of Poland’s commitment to Zionism and the fundamental differences between Poland’s Jewish policy and that of the Nazis.

In the sections that explore this supposed alliance, however, Snyder’s historical account becomes shaky, and several disturbing assumptions on Polish-Jewish history emerge. For one, Snyder never explains why Poland—if it indeed was committed to creating a Jewish state—would lay its bet on the Zionist Revisionist movement, a rather small and politically weak group within the Jewish world of the 1930s, and on a fantasy of an armed rebellion against the British Empire (which was by no means an enemy of Poland) more than a decade before the era of decolonization began. This seemingly fantastical aspect of the alliance has prompted other historians to interpret it not so much as a concrete political plan by Poland to reshape the imperial order in the Middle East but in part as a propaganda ploy designed to serve Polish domestic and foreign political needs. David Engel and Eli Tzur observed that Poland’s support for Revisionist Zionism was used to deflect international accusations against the country’s domestic anti-Jewish policies. Jabotinsky’s advocacy for the evacuation of millions of Jews from Eastern Europe helped the Polish government make the case that its own support for Jewish emigration was not anti-Jewish but pro-Zionist. Laurence Weinbaum has noted that during the 1930s the Polish government was under severe public pressure to act against Jewish preponderance in various economic sectors. A public alliance with the Revisionist movement was thus used to instill the impression that the government was about to provide an imminent solution to its Jewish problem. Indeed, as Weinbaum further notes, although the Polish government trained and provided funds for Revisionist activists, it always remained hesitant about the alliance, in part because Polish officials feared the detrimental effects it could have on their relationship with the British. By making this alliance a centerpiece of his historical account of Polish-Jewish relations, Snyder simply reproduces the propagandistic rhetoric the Polish government sought to promote in the late 1930s.

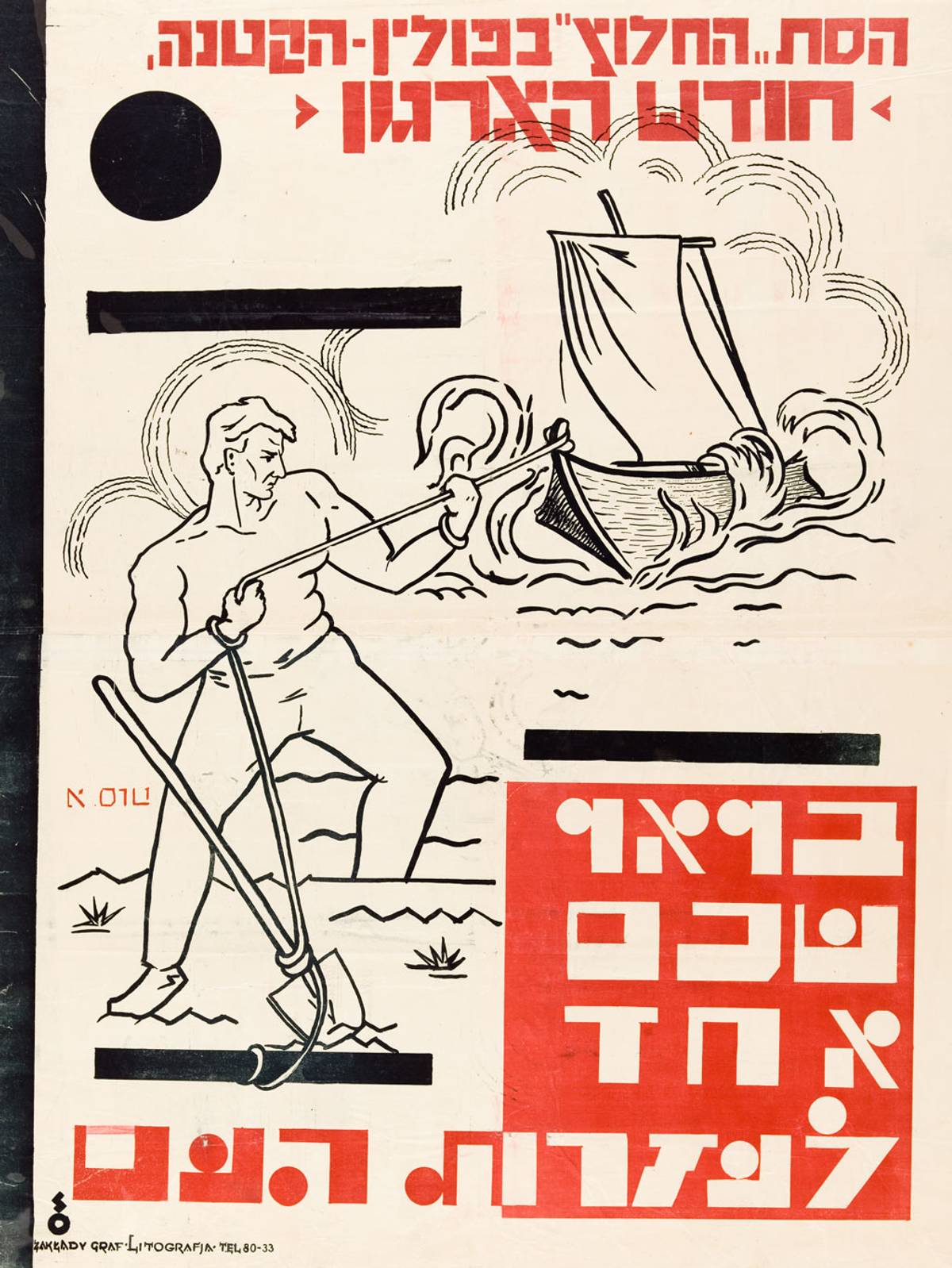

Propaganda poster for Hekhalutz’s “Organization Month,” with the slogan: “Come with one shoulder to the aid of the people,” Poland, 1930s. (From the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York)

If the Polish-Zionist Revisionist alliance was historically far more tenuous than Snyder admits, then so is the very assumption that underpins his discussion of it—that the “essence” of Polish foreign policy in the 1930s was to create a Jewish state in Palestine. Here, too, Snyder’s account seems to reproduce the rhetoric of prewar Polish governments. Poland’s major policy aim with regard to the Jews was not to create a Jewish state in Palestine but to promote the emigration of 90 percent of its Jewish population: The creation of a Jewish state in Palestine would have certainly made this goal far easier to achieve. But Jewish statehood—or an increase in British immigration certificates to Palestine—was never a precondition for the enactment of anti-Jewish measures. The question of the future destination of the Jews was always secondary: What mattered was that the Jews leave, whether to Palestine, or, as some Polish leaders proposed, Madagascar.

The presentation of Poland’s policy in support of Jewish emigration as pro-Zionist leads Snyder to read anti-Jewish measures as essentially benign, even humanitarian. Oscar Janowsky, a historian of Eastern European Jewry, was not particularly subtle when describing the hypocrisy behind Poland’s attempt to push the Jews out and then claim to support statehood for them. The Polish government, he wrote in 1936, is acting “not unlike the person who murdered man and wife and then appealed to kind people to help send the orphans to an asylum.”

Equally startling is Snyder’s discussion of German-Polish negotiations on the Jewish question in 1938. To convince Poland to join Germany in an attack against the Soviet Union, Hitler promised Poland territorial gains and a solution to its Jewish problem—possibly a large-scale deportation of Jews to Madagascar. Snyder discusses these negotiations twice in his book in order to highlight the radical differences between German and Polish thinking about the Jewish problem. The Nazis, Snyder writes, understood Madagascar as euphemism for extermination. The Poles thought about it as a specific place, alongside Palestine, for large-scale Jewish immigration. Polish leaders were thus “weary” and “confused” in their meetings with the Germans, for “they simply could not understand how the Germans meant to invade the Soviet Union while deporting the Jews of Europe. … In simple logistic terms the idea made no sense.” Snyder is no doubt right that Germans and Poles had very different ideas about the proper solution of the Jewish problem, even if his portrayal of Polish diplomats as a group of naïfs who could not guess the intentions of the Nazis strikes me as implausible. Still, it is hard to escape the feeling that in repeatedly emphasizing the ideological differences between Germans and Poles an equally important historical observation eludes Snyder’s account—that their actual policies on the Jewish problem on the eve of the war were remarkably similar. Snyder recounts the details of the well-known Zbąszyń affair—in 1938 Poland stripped tens of thousands of Polish Jews residing abroad of their citizenship to prevent their return from the Reich to Poland, only to see Germany expel them back to Poland (where they would remain stranded for months in a camp on the Polish border). Yet he nowhere draws the conclusion that on the eve of the war both Poland and Germany had begun to experiment with denationalization and the creation of zones of Jewish statelessness. The similarities between Germany and Poland’s Jewish policies are never explored; only the differences.

The differences between Polish and Nazi anti-Semitism are emphasized again as Snyder turns to discuss Polish interwar anti-Semitism. After 1935, the Polish regime used economic pressure to induce Jews to leave; turned a blind eye to boycotts of Jewish businesses; passed a ban on kosher slaughter (though the ban was never implemented); in the universities, Jewish students were beaten and relegated to the last rows or “ghetto benches”; and the clergy and right-wing leaders spread antisemitic propaganda. Yet while Snyder notes that “the vision of a future Poland without most of its Jews was certainly anti-Semitic,” he adds that it “was not an anti-Semitism that identified Jews with the fundamental ecological or metaphysical evil of the planet.” Unlike in Germany, in Poland Jews were just seen as “human beings whose presence was economically and politically undesirable.” For an understanding of Polish Jewish history in the 1930s, this is a distinction without a difference.

So, what is it that we learn about the history of anti-Semitism in Poland by recognizing that Jews were just undesirable human beings rather than a metaphysical-ecological evil? This distinction seems to matter for a different type of argument Black Earth covertly posits—that in order understand the causes of the Holocaust there is no need to turn to interwar Poland, because none of its ideological roots are to be found there. Snyder’s account seems to go even a step further: Not only could Polish anti-Semitism in no way account for or explain the Holocaust, but Polish anti-Semitism could in fact have saved the Jews. One of the chief arguments of Black Earth is that the perseverance of state structures was the only guarantee for Jewish survival in the war. According to Snyder, an examination of Jewish survival rates in the war shows that where states remained, Jews survived, where states were destroyed, Jews were murdered. Where states were destroyed twice (Nazi and Soviet occupations), the murder rate of Jews was highest.

In the conclusion, Snyder notes that Revisionist Zionists were correct in their analysis of the Jewish condition in the 1930s: “Zionists of all orientations were correct to believe that statehood was crucial to future national existence. … The Revisionist Zionists of the Far Right were correct in fearing an imminent catastrophe in the 1930s and reasoned that covert cooperation with the Polish state was therefore justified.” It is here that the reason behind the book’s inordinate preoccupation with the history of the Polish-Revisionist Zionist alliance becomes clear. If the state was the only guarantee for Jewish survival, and if Revisionist Zionists were correct to call for the evacuation of millions of Polish Jews to a Jewish state in the 1930s, and if the Polish government was the greatest ally of the Zionist Revisionist movement, could not Polish anti-Semitism be interpreted in retrospect as a form of humanitarian foresight?

This position sounds preposterous until one realizes that Polish leaders and intellectuals voiced it after the war. Count Ludwik Łubieński, personal secretary to Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck in the 1930s, wrote in 1964 that “in my opinion Jabotinsky was one of the few Jewish activists or politicians who understood that Poland was in essence the best friend of the Jewish cause and her staunchest ally.” In a similar vein, one Polish historian denied that Poland’s support for Jewish statehood was motivated at all by anti-Semitism: “Because of their own plight the Poles have always had sympathy for people who were deprived of their own independence.” Snyder writes: “The easy agreement between Jabotinsky and Polish leaders was not simply a matter of common interests,” for both Jabotinsky and Polish leaders had once been Russian imperial subjects and thus shared “the idea of building a nation-state from empires.”

By presenting Polish anti-Jewish policies as Zionist, Snyder allows visions of ethnic cleansing to masquerade as humanitarian agendas. He also overlooks an important moral and historical distinction—that between a Jewish and Polish supporter of Zionism in the 1930s. To be a non-Jewish Polish Zionist in interwar Poland was to argue that Jews do not belong in Poland and to call on Jews to immigrate elsewhere. To be a Jewish supporter of Zionism was to recognize that Jews were undesirable in Poland and to demand a state where Jews would be equals. Without putting this distinction front and center, we lose sight of an important historical fact—that Jewish life in Poland had become a “problem” or a “question” only because the Polish state and society regarded Jewish citizens as undesirable.

This distinction was not lost on one of the heroes of Snyder’s account—founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement, Vladimiar Jabotinsky. Though Jabotinsky is famous for his advocacy of the evacuation of millions of Jews from Europe, he was also deeply committed to the protection of the rights of Jews as a minority community in Europe. Jabotinsky was one of the architects of the 1906 Helsingfors Program that defined the goal of Russian Zionists as the fight for Jewish collective rights in the Russian Empire alongside the building of a Jewish state in Palestine. In the 1920s, Jabotinsky was a supporter of the League of Nations system of minority protection, calling on Jews not to give up on the “minorities dream” even as the system had failed to live up to its promises. Indeed, Jabotinsky shared the Jewish diaspora nationalist credo of his day: that the Jewish nation would develop thriving centers in both Palestine and eastern Europe.

Even as Jabotinsky advocated for Jewish evacuation from Europe in the 1930s, he did so alongside a demand that Poland issue a declaration promising Jewish equality in the Polish state. Speaking before a Jewish audience in Warsaw in 1936, Jabotinsky prided himself on being the architect of the Helsingfors Program and asserted that the “Evacuation plan” does not imply the end of the struggle for Jewish equality in Europe. It is important here to look at the numbers. Had the evacuation plan had been realized according to Jabotinsky’s wildest dreams, 1.5 million Jews would have been transferred from Eastern Europe to Palestine over the course of 10 years. Of those, 750,000 were to be Polish Jews. Millions more, Jabotinsky hoped, would immigrate in the decades that follow. Poland wanted 2.7 millions Jews out imminently. If the Polish government was ever Zionist, then its Zionism was infinitely more radical than that of Jabotinsky.

What is perhaps most remarkable about Snyder’s account of Polish-Jewish history is that he portrays Polish interwar anti-Jewish policies as Zionist within a book that otherwise directly confronts the history of anti-Semtisim. Synder’s previous history, Bloodlands, had been criticized for deemphasizing anti-Semitism by analyzing the Holocaust as a product of German-Soviet mutual radicalization. Black Earth opens with an introduction dedicated entirely to Hitler’s anti-Semitic worldview, arguing that Hitler had concluded already in the 1920s that all Jews must be exterminated. Snyder’s reading of Polish-Jewish history thus does not stem from a failure to see—or a desire to hide—anti-Semtisim, but rather from what might be described as the imposition of a radically nationalist narrative on Jewish history (a narrative that Jabotinsky would have found too radical). According to this view, Poles and Jews are inherently distinct national groups (a Polish Jew is a paradox). Since the best guarantee for the survival of Jews and of all national groups is a state, the most humanitarian solution to the Jewish question in interwar Poland was the creation of a Jewish state to which all Jews should be removed.

It is striking to note that this radically nationalist reading of Jewish history is on display in Snyder’s earlier works. In his pioneering The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus 1569-1999, Snyder traces the emergence of four nations out of the territory of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the introduction Snyder explains why the history of the Jewish nation—another national group that emerged out of the same territory—“must await a separate treatment.” Snyder provides several reasons and writes that “twentieth century territorial nationalism aspiring to repatriation the old Commonwealth into nation-state was never an option for the Jews,” and that a study of the history of the Jewish nation “would draw us away from the Eastern Europe territorial focus,” that is, to Palestine. But in presenting the Jews of Eastern Europe as essentially a precursor to a nation-state in the making in Palestine, Snyder glosses over another possibility: Why not write the history of Jews and of the Jewish nation as rooted in Eastern Europe, where even the likes of Jabotinsky believed Jews would remain for a very long time?

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.