Politics and Poetry

Trying to make sense of Shakespeare’s politics, a complicated web of ideas and contradictions that attracted and repelled some of modern history’s most notorious leaders

I recently published a book about Shakespeare’s impact on the material world—on things like the existence of starlings in North America, the assassination of Lincoln, and the sexual revolution, among others—but Shakespeare’s influence on politics was the hardest part of the book to write. What were Shakespeare’s politics? Four hundred years after his death, anyone with an interest in sounding grandiloquent can cull a telling phrase from one play or another: Liberals can mumble about “the winter of our discontent” and conservatives can bluster that “the lady doth protest too much.” The greatest modern practitioner of the Shakespeare quote for political purposes was the late Sen. Robert Byrd, who repeatedly found obscure and beautiful lines from little-known plays like Henry VIII or King John. But Shakespeare, I found out, can mean many things to many people.

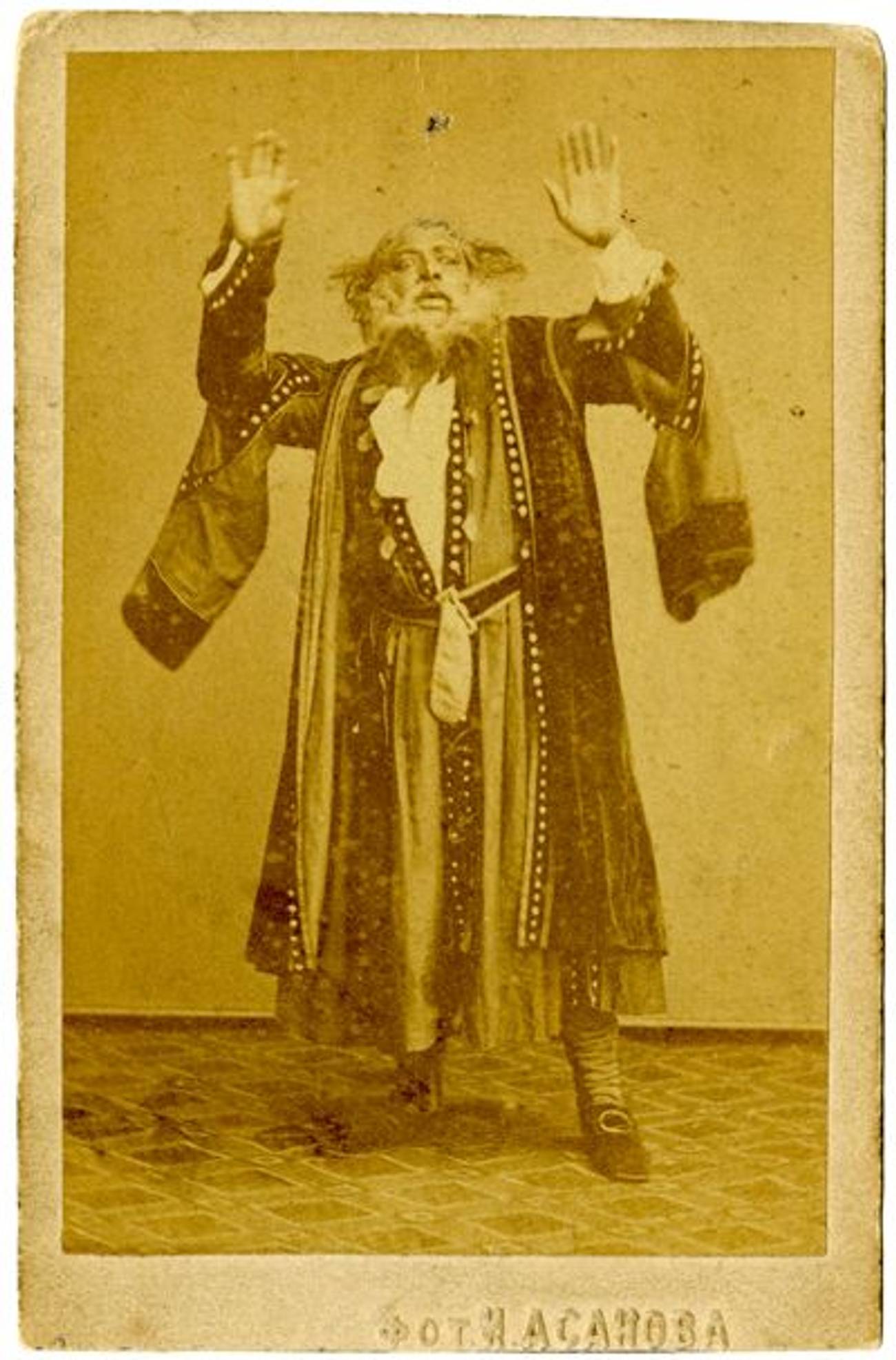

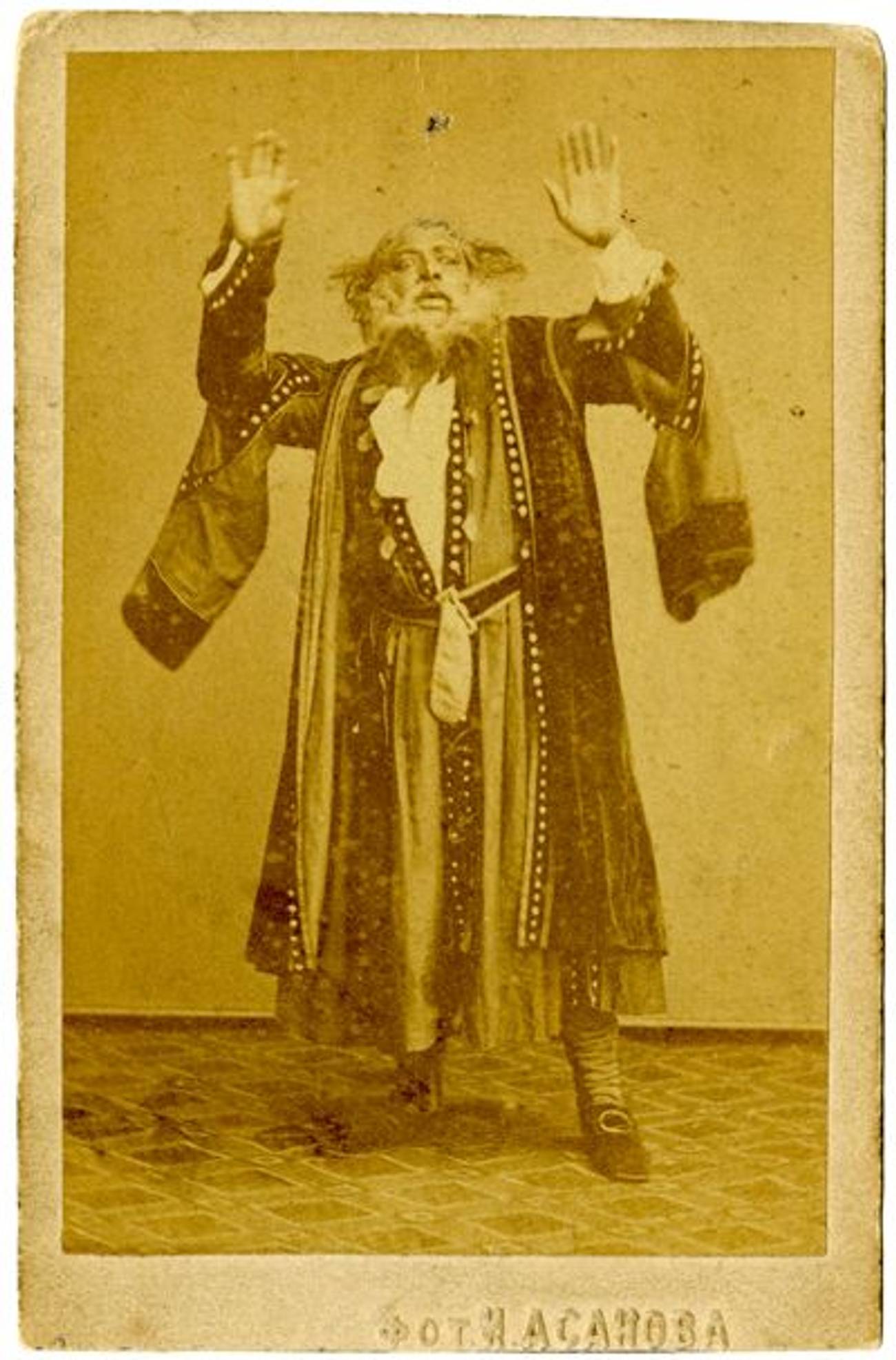

Take Hitler, for example. A few months after he became chancellor of Germany, the Nazi Party issued a pamphlet titled Shakespeare—a Germanic Writer, and in 1936, there were more productions of Shakespeare in Germany than in the rest of the world combined. Joseph Goebbels’ favorite professor at Heidelberg was the Jewish Friedrich Gundolf, author of Shakespeare and the German Spirit. But Shakespeare fought on both sides of the divide: The Communists under Stalin elevated Shakespeare to the ranks of the “Great Thinkers of the Age,” a list that culminated in Lenin and Stalin. During the Stalin era, more than 5 million copies of Shakespeare were published in the 28 languages of the Soviet Union, and thousands of productions of his plays were authorized. (Stalin, however, reportedly frowned on productions of Hamlet, disliking the Danish prince’s indecisiveness.)

And yet, even though Shakespeare served the nastiest totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, he also became a tool for resistance against them. Hitler’s Germany loved Shakespeare but also feared him. Ironically, the one play they couldn’t handle was The Merchant of Venice, whichlanguished after 1933. In 1938, Merchant was placed on the blacklist, to be confiscated from libraries. The Nazis and their Ministry of Propaganda feared two of the play’s most salient features: Shylock’s “Hath not a Jew eyes” speech (and since he has only five appearances in the entire play, it becomes complicated to cut any of his speeches) and his daughter Jessica’s marriage to a non-Jew, which was illegal under Nazi law. One major production avoided this embarrassment by making Jessica a foster daughter rather than a blood relation, cutting Shylock’s key line from the third act, “My own flesh and blood to rebel!” Still, Nazi officials took no risks with that production. They hired actors to sit in the audience and shout insults at Shylock whenever he entered.

In Eastern bloc countries, in the second half of the 20th century, Shakespeare grew more and more of a worry to the authorities. Polish critic Jan Kott’s absurdist reading of the plays, Shakespeare Our Contemporary, was banned across the Communist world. After the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia, productions of Shakespeare became a major avenue for protest. The Theatre on the Balustrade in Prague, in January 1969, put on a Timon of Athens rife with disillusionment and coded messages about the invading Soviets. The actors even added a rhyming couplet to the end of Act 3, scene 1: “Those that have power to hurt and smother/ Will heap one injury upon another.” The cultural officials of the state caught on to these coded performances quickly enough and banned them. But they couldn’t stop everybody from performing Shakespeare. In 1978, three dissident actors who had been banned from performing in Czechoslovakia did one of the silliest and most beautiful Shakespeare performances ever conceived: They called themselves the Living-Room Theatre, and they put on Macbeth in the privacy of their own homes. Shakespeare became a way for actors without a stage to assert themselves.

Shakespeare serves many political masters but none of them faithfully, and ambivalence about the relationship between power and art riddle his plays. After Marc Anthony’s stirring funeral oration in Julius Caesar, the enraged crowd stumbles on Cinna the poet, whom they confuse with one of the conspirators, also named Cinna.

Third Plebian: Your name, sir, truly.

Cinna: Truly, my name is Cinna.

First Plebian: Tear him to pieces! He’s a conspirator.

Cinna: I am Cinna the poet, I am Cinna the poet.

Fourth Plebian: Tear him for his bad verses, tear him for his bad verses.

Cinna: I am not Cinna the conspirator.

First Plebian: It is no matter, his name’s Cinna; pluck but his name out of his heart, and turn him going.

The crowd doesn’t just kill Cinna. They rip him apart. Which is remarkable for two reasons. Ripping a poet apart is not only exceedingly violent but also nearly impossible to stage. Not only is the crowd mad in its rampaging violence; it is consciously mad, aware that it is slaughtering an innocent for no good reason. The pathetic excuses of the plebians are even more horrifying than the violence they are trying to cover. The crowd is not just mistaken. It revels in its own stupidity, a phantom reminiscence of the self-conscious barbarism of the Nazi mobs.

In Julius Caesar, art is a casualty of power, but in Hamlet, it’s the opposite: Art redeems history. The play-within-the-play is how the prince figures out whether to kill his uncle. A work of theater proves the justness of the assassination: “The play’s the thing/ Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King.” During the performance of The Murder of Gonzago in the play’s third act, the murdering usurper Claudius calls for light, and Hamlet howls, “What, frighted with false fire?” For such a complicated play, the relationship between art and power is surprisingly simple. The play-within-a-play shows Claudius a direct representation of his own crime, and he cracks. All it takes is a clear representation of the cruelty of power to reveal what it is and what to do about it.

So, Shakespeare gives us a double vision. Power rips art to pieces. And art reveals the hidden crimes of the powerful. Shakespeare predicted his own abuse and redemption. Just like with Cinna in Julius Caesar, he was torn apart by Nazi and Communist mobs, and just like with Hamlet and his uncle Claudius, his plays have offered false fire to startle the guilty heart of power everywhere.

So, how are we to judge the bard as political figure? How are we to tote up his effects on the world of power politics? After massive public criticism of a performance of The Merchant of Venice at the Habimah Theater in Palestine in 1936, the theater responded by organizing a mock trial for Shakespeare just as Shakespeare had organized a trial for Shylock. The accused were William Shakespeare, the director Leopold Jessner, who had been a major power in Berlin’s theatrical world before the Nazis came to power, and the Habimah Theater itself. Needless to say, in Israel, where any two people in an argument have three opinions, the prosecution and defense were both shambles. Traditionalists argued that Shylock could not have been Jewish, because revenge was not a Jewish practice. The socialists argued that Shylock was a warning to the creeping spirit of speculation and profiteering starting to rear its head in the burgeoning state. In other words, Shylock was the wrong kind of Jew, not a Jew, or the ultimately wronged Jew all at the same time. The Merchant of Venice has been performed throughout Israel’s history—after the founding of the state, after the conquests of 1967, after the beginnings of the intifada. In each case, it has provoked massive outcry and defense.

Germany after World War II, as the only nation in the world that has honestly tried to confront its historical crimes, has also had a fraught relationship with Merchant. After an initial series of “expiation Shylocks” in which the character was played as an innocent, more sinned against than sinning, Germans began to incorporate their own past into the play. In a 1995 adaptation, the premise was Jewish prisoners at Buchenwald performing the play for their SS guards, after which all the actors were killed. A later German production incorporated scenes from Merchant into a concentration-camp narrative that converts the play’s plot into scenes of Nazi torture. The moral simplicity of such outrage doesn’t fit the complexities of history: The Nazi guards supposedly watching The Merchant of Venice for their amusement would, in reality, have been quite offended by the play. Despite the discomfort of the Israelis and the Germans, Shylock was too human for actual Nazis. Consider his most famous speech:

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, sense, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is?—if you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die? And if you wrong us shall we not revenge?

Does it make this passage more brilliant or less that it comes out of the mouth of a stock Jewish villain? Shakespeare insists on the humanity even of people he stereotypes. That’s the core of the Shakespeare’s politics. The 20th century produced several extended experiments in the ways that men and women can be turned into objects to be processed or destroyed at will. Our common humanity is a massive embarrassment to this programme. Shakespeare insists on this embarrassment.

If, as George Orwell claimed, the future is a boot stamping on a human face over and over, Shakespeare has put human faces on display over and over in response. He insists above all on the fascination of his characters, on their indestructible personhood. Or, to put it another way: Like everyone else, like Hitler and Stalin and Churchill, I have found in Shakespeare the confirmation of my own political views—in my case an unremarkable but passionate brand of bland 21st-century humanism. Everybody finds what he or she is looking for, and I’m no exception.

Stephen Marche is the author of the newly released How Shakespeare Changed Everything, from which this piece is excerpted.

Stephen Marche is an Esquire columnist and the author, most recently, ofThe Hunger of the Wolf.