Progressive Replacement Theology

Why the left is repeating Christianity’s most dangerous historical mistakes, and why it’s very, very bad for the Jews

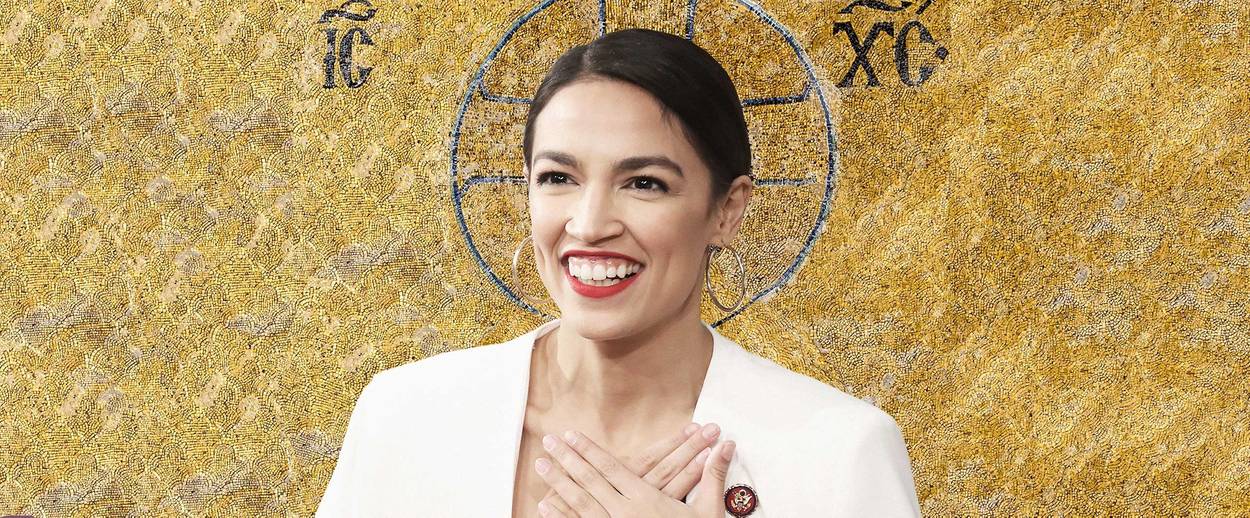

We live in strange political times, so it’s no wonder that we’re called upon to address strange political questions. A few stand out: Is Ilhan Omar, the Somali-born Democrat representative from Minnesota, right to call herself the first refugee in Congress, even though several Holocaust survivors preceded her? Is Julia Salazar, the newly elected New York state senator Jewish, which she claims to be even though members of her family refute her account of their genealogy? Is Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the daughter of Puerto Rican parents, Jewish because, as she recently argued, her ancestors were Sephardic Jews? Does that mean that anyone who could trace some fraction of Jewish ancestry—which includes nearly all of Latin America and vast swaths of the rest of the world—is now Jewish? Can you become Jewish merely by rising one day and declaring yourself passionately affiliated with the Jewish people? Is arguing otherwise racist and exclusionary? If so, does that mean that tikkun olam is the true essence of Judaism, and that those who practice it are the real Jews even though they may otherwise commit their energy to arguing that the Jews are the only people on earth undeserving of a state in their national homeland, where they have lived continuously for nearly three millennia? And are people who oppose progressivism un-Jewish, even if they observe Jewish rituals daily, study Jewish texts, and lead dedicated Jewish lives?

I’m a simple Jew, and these are profoundly meaningful quandaries I’m only too happy to let others address. I would, however, like to suggest that the above, at the heart of so many of our most heated debates these days, all have one thing in common: They all revolve around the newfound and bizarre desire of progressives to further their arguments by claiming that they, somehow, are the new Jews.

The reason for this strange turn, I believe, lies not in the passions of our partisan political moment but in the early history of Christianity, which provided Western civilization with much of its cultural template. And as much as the idea of Western civilization might make progressives twitch in discomfort, they are very much a part of it, even as their rejection of its religious roots makes them more vulnerable to repeating the most deadly mistakes of their forebears. What we’re seeing right now, then, is the strange spectacle of progressives pursuing the same thorny theology that much of Christendom abandoned long ago, the theology of supersessionism.

Also known as replacement theology, this idea developed early on in the history of Christianity, and for obvious reasons. If the New Covenant, through Jesus Christ, meant that Christians were God’s new chosen people, what, then, was to be done about the chosen people of old, the Jews?

To some fathers of the church, it wasn’t a particularly difficult question to answer. By rejecting Christ, they reasoned, the Jews had forfeited their right to their special status, had broken their covenant with God, and were worthy of nothing but wrath. That was certainly the opinion of Origen: Born around 184 CE in Alexandria, he hoped to martyr himself as a Christian when he was 16, but his mother, panicked, hid all his clothes: He refused to leave the house and turn himself in to the Roman soldiers naked. Instead, he became an ascetic, giving up meat and drink and, reportedly, paying a surgeon to have himself castrated so that he may transcend the temptations of the flesh. He composed thousands of theological treatises, but he hit his stride, it seems, when writing about the Jews. “And we say with confidence,” he wrote, “that they will never be restored to their former condition. For they committed a crime of the most unhallowed kind.” Writing around the same time, Hippolytus of Rome, one of the most important early Christian theologians, was even more prescriptive: The Jews, he thundered, “have been darkened in the eyes of your soul with a darkness utter and everlasting. … Furthermore, hear this yet more serious word: ‘And their back do you bend always.’ This means, in order that they may be slaves to the nations, not four hundred and thirty years as in Egypt, nor seventy as in Babylon, but bend them to servitude, he says, ‘always.’”

There were, of course, better answers to the question of how to think about the Jews, and, of course, it was Augustine who alighted on them. While not abandoning the supersessionist claim altogether, the early Christian theologian was, as ever, the smartest person around, and he offered his fellow Christians a better alternative. The Jews, he argued, were Christianity’s witnesses: “But the Jews who slew Him,” he wrote, referring, naturally, to Jesus, “are thus by their own Scriptures a testimony to us that we have not forged the prophecies about Christ.” See things this way and the Jews are no longer worthy of eternal servitude. Instead, they become intimates of their Christian brothers and sisters. “For in the Jewish people was figured the Christian people,” Augustine wrote. “There a figure, here the truth; there a shadow, here the body.”

Augustine’s ideas, the theologian John Y.B. Hood stated, “dominated the medieval debate,” and James Carroll, the former priest and bestselling author of Constantine’s Sword, a history of the church and the Jews, stated bluntly that “it is not too much to say that, at this juncture, Christianity ‘permitted’ Judaism to endure because of Augustine.”

It wasn’t, sadly, a very permissive permit. While the Celts and the Druids and the other tribes who came under the church’s rule could be slaughtered or assimilated or otherwise made to disappear, the Jews continued to pose a special problem: Christian civilization, it seemed, often couldn’t live without them, and even more often couldn’t live with them. And so, the Jews were mocked, discriminated against, relegated to narrow ghettos, forced to convert, tortured by the Inquisition, expelled, accused, despised. But they persisted, because all but the most maniacal bigots understood that they were the children of God, and that their covenant with the Creator, even if you believed it to have expired, was still meaningful enough to respect, however begrudgingly.

And then came the Holocaust. The systematic murder of 6 million Jews marked an endpoint not only to Jewish life in much of Europe, but also, significantly and in a way that many Jews may still not appreciate, to the old problem Christianity had with the Jews. Having neither enshrined supersessionism in doctrine nor rejected it outright—it continued, throughout the centuries, to play a role in the thoughts and teachings of many of its lights—the Catholic Church, in its Second Vatican Council, drew a line in the sand that rejected the harshest aspects of replacement theology. In Nostra aetate, Latin for In Our Time, a declaration focused on the church’s relations with other religions, Rome made it clear that times have changed. “The Jews,” the statement read, “should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures. … Furthermore, in her rejection of every persecution against any man, the church, mindful of the patrimony she shares with the Jews and moved not by political reasons but by the Gospel’s spiritual love, decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.” The declaration was passed by a vote of 2,221 bishops to 88, and was officially released by Pope Paul VI in October of 1965. Fifteen years later, Pope John Paul II went even further when, visiting the synagogue in Mainz, he called the Jews “the people of God of the Old Covenant, which has never been abrogated by God.”

Evangelical Christians took the same sentiment in an arguably even more positive direction, often seeing Jews, for the most part, as beloved older siblings whose covenant and ideas coexist in harmony with those of Christianity here on earth. Often, left-leaning critics of this relationship take pleasure in pointing out that many conservative evangelicals also believe in the baroque idea of dispensational premillennialism, which includes the scenario that Christ will someday return to earth, whisk his followers to heaven, and then, after a terrible and all-encompassing war, return to govern in peace from Jerusalem for a thousand years, at which point the Jews (among others) will all follow his glory and convert. This frequently misconstrued idea does not mean, as some progressive pundits had unfortunately argued, that evangelicals hold secret designs for the eradication of the Jewish people. Instead, they believe in an eschatology that has much in common with Judaism’s version, which, too, believes in the eventual return of the Messiah, albeit with very different results. Yes, evangelicals believe that converting Jews is (to use language they wouldn’t) a mitzvah, since salvation and escaping hellfire require being born again in Christ. But because of the role Israel—the people and land—play in evangelicals’ eschatology, here and now on earth they are among Judaism’s most faithful friends and blessed supporters.

Not surprisingly, the same messianic fire illuminated many on the Christian left as well, who, starting at least as early as the 19th century, believed that Christ’s return may be hastened by making this world look more and more like His heavenly Kingdom by means of improving the lives of more and more individuals. Surprisingly, rather than allow this spirit to animate and grow it, the left, for the most part, instead compelled the West to abandon Christianity altogether.

Instead, a new faith emerged: progressivism. A time traveler, unaware of the developments of the last eight decades, might’ve been forgiven for listening to a modern-day progressive speak and mistaking her for a fundamentalist Christian: Jesus’ observation that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven sounds like something Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in a moment of inspiration, might say to an adoring interviewer on CNN. With its emphasis on social justice, criminal justice reform, elevating the poor, and rejecting the rapacious policies of the greedy and the affluent, progressivism sounds a lot like Christianity. Except that it has chosen to reject Christianity and all other forms of faith as silly superstitions, to abolish history by proposing that it has but one throughline—progress!—and to set up instead a religion that fails to see itself as one and, as such, is condemned to repeat Christianity’s worst transgressions.

Beginning, sadly, with the Jews. In Ilhan Omar’s suggestion that none in Congress before her had been refugees, in Salazar and Ocasio-Cortez’s sudden and questionable claim of Jewish heritage, even in the rush of many on the far left to argue that Jews of color are the real Jews and that the rest of us are somehow complicit in Klan-like prejudice—in all these we see the old wheels of replacement theology turning. Judaism may have given us much understanding of justice, but if progressivism is to claim its modern-day mantle, Judaism has to be argued away, which begins by anointing the progressives the real new Jews.

If you doubt that any of this is true, try for a moment to think rationally about the way most progressives talk about Israel. Let us, for the sake of argument, assume for a moment that those who assiduously claim that anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism are not interchangeable are correct. Let us accept that one may have a host of pressing critiques of Jerusalem and its policies. What, we may now ask, are those all about? To hear many American progressives tell it, Israel is worthy of special attention because of the inordinate amount of American foreign aid it receives. If that were the case, we could safely assume that as Israel receives about twice as much aid as, say, Egypt, we might expect our media to write one story about Egypt’s transgressions for every two they write about Israel. The ratio, sadly, is very different. It’s skewed, too, if you compare the uproar about Israel to the attention paid to other areas of conflict and human rights violations around the world: Everywhere you look, the world’s only Jewish state is singled out for calumny. The reason is simple: Israel provides progressivism’s zealots with a convenient opportunity to mask their theological decrees as rational, reasonable, and worldly politics. By focusing all of your attention, energy, and rage on the Jews, you may declare yourself, just as Origen and Hippolytus had centuries ago, to be the rightful heir to an enlightened tradition abandoned by those who were once God’s chosen people but who are no longer.

You’d hope that the tenured hordes that make up so much of progressivism’s vanguard would know all this, but religious extremism, as Jewish history has tragically proved again and again, is blinding. We can only hope that one day soon a progressive Augustine may arise and temper the hate of his new secular faith. Until then, we Jews should do what we’ve done so gallantly for millennia and protect ourselves against the spurious claims of fanatics with dangerous ideas.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.