Death to Me!

‘The New York Times’ and the creepy personal and ideological logic of public confessions

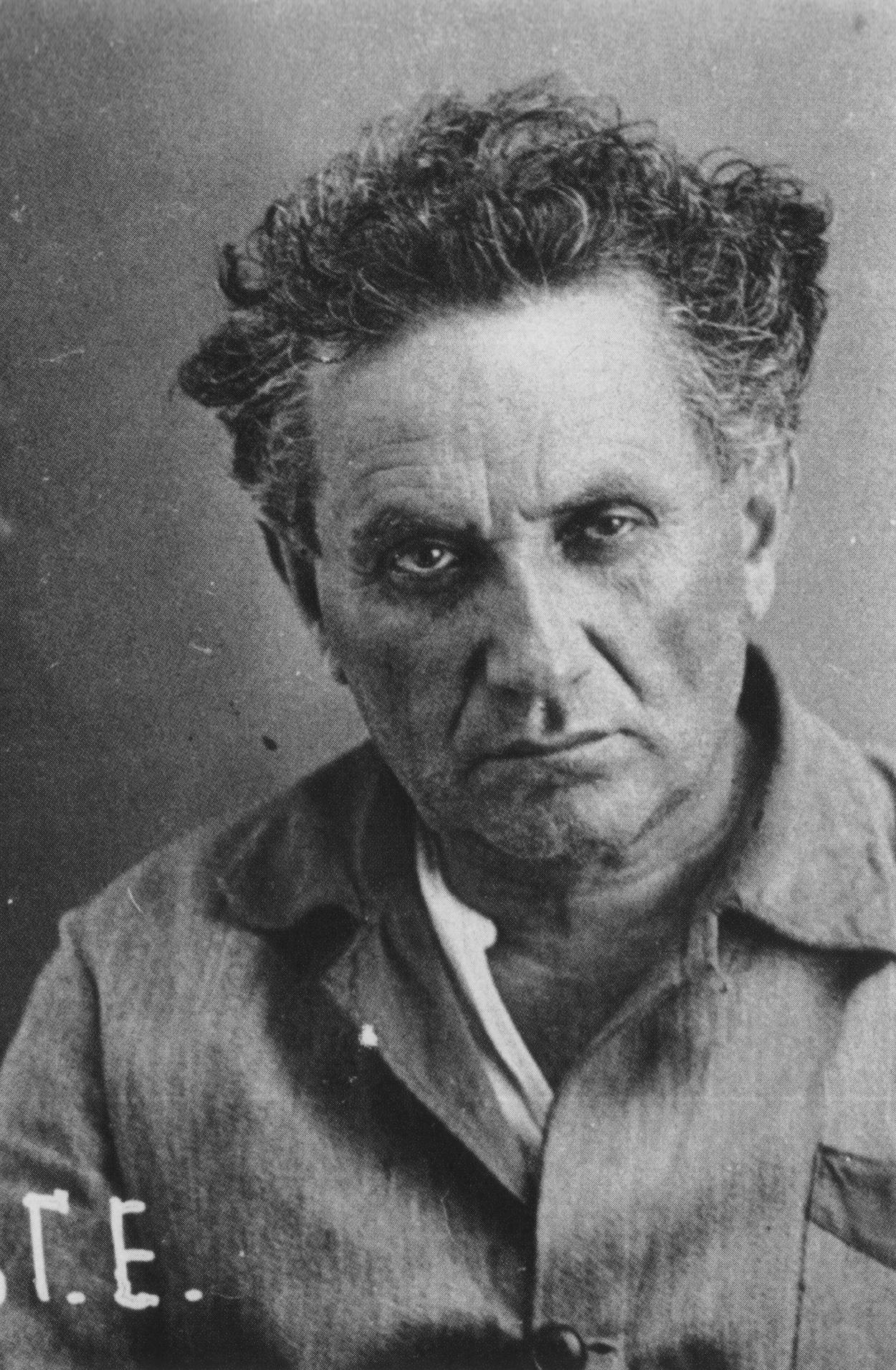

“And here I stand before you in filth, crushed by my own crimes,” confessed Yuri Pyatakov in January 1937, “bereft of everything through my own fault, a man who has lost his Party, who has no friends, who has lost his family, who has lost his very self.” Pyatakov, once the head of the Soviet State Bank, admitted his crimes of Trotskyism and Hitlerism after a month of being tortured by an old friend, Nikolai Yezhov, head of the NKVD.

Yet the accused in Stalin’s show trials confessed for many reasons beyond the rigors of interrogation and torture. Sometimes they hoped to save themselves or their families through an energetic performance, as in the cases of Grigori Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, Stalin’s old allies, who were judged and executed during the 1936 Moscow Trials. (“Some hoped to save their heads, others at least to save their wives or sons,” Arthur Koestler wrote.) Sometimes they found it unthinkable to betray the party, even if they had lost faith in Stalin. As Nikolai Bukharin, once Stalin’s equal in the party leadership, remarked in 1935, “It is not [Stalin] we trust but the man in whom the Party has reposed its confidence.” Trotsky himself declared in 1924, before he became Stalin’s archenemy, that “we can only be right in and through the Party, for history has provided no other way of being right.”

The ice-cold logic of Marxism dictated that it was impossible to dispute, or even wish to dispute, the will of the party. As Pyatakov wrote, “For such a Party a true Bolshevik will readily cast out from his mind ideas in which he has believed for years.” The party was a lifeline, a mother, a god. Bukharin said, “For three months I refused to say anything. Then I began to testify. Why?” Bukharin explained that “an absolutely black vacuity suddenly rises before you with startling vividness.” You have to give your death a meaning, and the only real meaning is to sacrifice yourself for the party in whose will you long ago drowned your own.

Bukharin’s remarks were the seed of Koestler’s Darkness at Noon and Orwell’s 1984. Koestler went on to stress the basis for the Bolsheviks’ guilt feelings, namely their constant betrayals and murders. Bukharin and so many others had blood on their hands, and their confessions were a way to expiate their real crimes.

The role that public confessions play in demonstrating and validating the power of ideologies that refuse any criticism is worth revisiting for the obvious reason that such confessions are now part of our culture, too. Now, as then, the most baffling and disturbing aspect of these confessions is the enthusiasm with which the accused embrace their supposed guilt.

Many have wondered why the Soviets spent so much time procuring confessions at all. The answer is clear: In the absence of real evidence and reporting, public confessions helped buttress the credibility of the system. Even skeptics might think there was a grain of truth to the charges. And the outside world was, for the most part, easily convinced.

Last Friday, Donald G. McNeil Jr., a science reporter for The New York Times since 1976, and one of the mainstays of the paper’s coverage of the coronavirus pandemic—a matter of life and death for millions of people around the planet—was forced to leave the paper. “Dean and Joe” (Dean Baquet, the paper’s executive editor, and Joe Kahn, managing editor) announced to Times staffers that McNeil had cited a racial slur in a conversation with two high school students, and therefore had to go, since “We do not tolerate racist language regardless of intent” (italics mine; I will come back to those words later). The editors then helpfully appended McNeil’s resignation letter to their email:

To the staff of The Times:

On a 2019 New York Times trip to Peru for high school students, I was asked at dinner by a student whether I thought a classmate of hers should have been suspended for a video she had made as a 12-year-old in which she used a racial slur.

To understand what was in the video, I asked if she had called someone else the slur or whether she was rapping or quoting a book title. In asking the question, I used the slur itself.

I should not have done that. Originally, I thought the context in which I used this ugly word could be defended.

I now realize that it cannot. It is deeply offensive and hurtful. The fact that I even thought I could defend it itself showed extraordinarily bad judgement. For that I apologize.

To the students on the trip, I also extend my sincerest apology. But my apology needs to be broader than that.

My lapse of judgment has hurt my colleagues in Science, the hundreds of people who trusted me to work with them closely during this pandemic, the team at “The Daily” that turned to me during this frightening year, and the whole institution, which put its confidence in me and expected better.

So for offending my colleagues—and for anything I’ve done to hurt The Times, which is an institution I love and whose mission I believe in and try to serve—I am sorry. I let you all down.

Donald G. McNeil Jr.

If I were Donald G. McNeil Jr., I would want to tell The New York Times, and its publisher, A.G. Sulzberger, to go jump in a lake. Instead, McNeil chose to declare his love for the paper and proclaim his guilt for having “hurt” many hundreds of people. For McNeil’s professional death to have meaning, the party—or the paper—must be infallible. Death to me!

That this kind of groveling confession is not unique to the Times, but rather plays a key functional role in the politics of woke anti-racism, can be judged with the frequency with which such apologies are staged across institutional and corporate settings where wokeness holds sway. Consider this open letter by an academic named Matthew J. Mayhew who, after weeks of bullying and abuse, publicly recanted a seemingly anodyne op-ed he wrote for Inside Higher Ed expressing his enjoyment of college football as a distraction—one with the capacity to unite us all during the pandemic. Apparently, Mayhew learned a lot from the furious reaction of his colleagues to such an ignorant, hateful, and deeply damaging viewpoint:

I learned that I could have titled the piece “Why America Needs Black Athletes.” I learned that Black men putting their bodies on the line for my enjoyment is inspired and maintained by my uninformed and disconnected whiteness and, as written in my previous article, positions student athletes as white property. I have learned that I placed the onus of responsibility for democratic healing on Black communities whose very lives are in danger every single day and that this notion of “democratic healing” is especially problematic since the Black community can’t benefit from ideals they can’t access. I have learned that words like “distraction” and “cheer” erase the present painful moments within the nation and especially the Black community. ...

I am just beginning to understand how I have harmed communities of color with my words. I am learning that my words—my uninformed, careless words—often express an ideology wrought in whiteness and privilege. I am learning that my commitment to diversity has been performative, ignoring the pain the Black community and other communities of color have endured in this country. I am learning that I am not as knowledgeable as I thought I was, not as antiracist as I thought I was, not as careful as I thought I was. For all of these, I sincerely apologize.

Up with the revolution!

Untold millions of true believers lived and died in Stalin’s Soviet Union. When told they were guilty, they sooner or later agreed with the charges against them, even if they couldn’t locate their guilt in anything they had actually done. When the exhausted prisoner finally gives in to the party, which has sole grasp on truth, a soothing relief may come: History has spoken. Koestler and Orwell testify as much in their famous novels.

Admittedly, at times the prisoners were merely surrendering to a superior force that worked through the deprivation of sleep and food and relentless interrogations—and through more baroque tortures. And there were always those who refused and resisted. But the Soviet system stood for decades on the bedrock of shared guilt.

In the absence of real evidence and reporting, public confessions helped buttress the credibility of the system.

Reporting for The New York Times about the Moscow Trials of 1936, Walter Duranty commented that “it was unthinkable that Stalin and Voroshilov ... could have sentenced their friends to death unless the proofs of guilt were overwhelming.” Other newspapers signed off on Stalin’s executions, too. In fact, the New Statesman (Sept. 5, 1936) argued, the defendants had demanded the death sentence for themselves! Surely they must have been guilty.

Stalin’s most celebrated victims were themselves used to humiliation and self-abasement. As Robert Conquest writes in his indispensable book The Great Terror, “Their surrender was not a single and exceptional act in their careers, but the culmination of a whole series of submissions to the Party that they knew to be ‘objectively’ false.” Conquest tells of a former member of the Soviet Supreme Court who was informed by an interrogator, “Well, the Party demands that you, as a Bolshevik, confess that you are an English spy.” The man responded: “If the Party demands it, I confess.”

These days we repeatedly confess our racism and misogyny, suppressing any sense that we are perhaps not as sinful as we are told. Maybe we haven’t harassed, demeaned, or insulted anyone—but the very impulse to defend ourselves indicates our guilt. After all, we are all part of “the system,” and only a thoroughgoing racist would dispute the idea that the system is guilty.

Of course, America is not Soviet Russia, or, for that matter, Xi’s China. Our new political commissars don’t use torture, prison cells, and executions. Today’s woke ideology can be publicly attacked, unlike communism in the Soviet Union. Its critics are in fact legion: According to polls, most Americans of all genders and ethnicities think political correctness is a problem. But people are afraid for their careers, and so they remain silent—no matter how much “power” or “privilege” they ostensibly have.

For those who believe in the power of institutions to moderate the ideologically driven madness of this moment, the most worrisome aspect of McNeil’s firing is the about-face of Dean Baquet, the paper’s editor. At first Baquet had declared, after an HR investigation of the Peru trip, that McNeil would stay. “He showed extremely poor judgment, but it did not appear to me … that his intentions were hateful or malicious,” Baquet wrote. While one can quibble with the word “extremely”—a sop to the woke—the editor’s decision was surely a reasonable one, given McNeil’s decades of meritorious service and the paper’s presumed need to provide its readers with informed reporting on the coronavirus crisis.

Yet a few days later, Baquet abruptly reversed himself, and McNeil was fired. What changed? Had some new, damning piece of evidence surfaced? No, only a mob uprising, a familiar phenomenon at the Times of late. On Wednesday afternoon 150 Times staffers wrote a letter to A.G. Sulzberger demanding McNeil’s ouster. “Our community is outraged and in pain,” they lamented like the chorus of a Greek play. Oh, the fragility of the masses when they are set on vengeance!

“Our harassment training makes clear that what matters is how an act makes the victims feel,” wrote the Times staffers. Even if McNeil “didn’t act maliciously or with hateful intent,” they added, that doesn’t matter, since “intent is irrelevant.” Instead, what matters is the “victim’s” perception (fantasy? imagination?) of what happened. In other words, what had begun as a case about punishing stray bits of private conversation had become a contest over a very serious ideological precept—namely, the idea that the seriousness of a crime can and must be measured by its impact on its self-proclaimed victims. Anything can therefore be a crime, whose impact can in turn be beyond measure.

Yes, the students who complained about McNeil had parents who paid $5,500 for a two-week tour, suggesting that they were hardly an oppressed bunch. But they were “harmed” nonetheless, as was the entire staff of The New York Times. Among other things, McNeil, the Times staffers had learned, “reportedly made claims that white supremacy doesn’t exist,” a hanging offense. Moreover, there were rumors swirling that he “has shown bias against people of color … over a period of years.” Not one specific incident was cited in support of this claim, and indeed, none was necessary. Such vagueness lets readers freely imagine just how racist Donald McNeil Jr. is. Beyond measure would be putting things lightly.

Refusal to recite the required mantra that white supremacy rules America now leads directly to getting yourself fired. If you show resistance to the prescribed formula, you “hurt” many people: your colleagues, your employer, your community. Your recalcitrance in admitting the fullness of your guilt only increases the harm that you are causing. Though the only concrete speech crime that anyone could cite was McNeil’s repetition of the N-word, that would have to do.

Racist language must be forbidden “regardless of intent,” Baquet and Kahn decided. Astoundingly, the editors of The New York Times are now on the record saying that the mere appearance of a word in one’s mouth renders one guilty, “regardless of intent.”

OK, fine. If that utterly nonsensical standard indeed applies at The New York Times, then let’s consider the evidence of the paper’s own guilt: A quick search of the Times archives reveals a total of 135 uses of the N-word and 23 uses of a common slang variant over the past five years.

Though you might not want to type that word in the search bar, if you value your job, consider what this terrible number says about the paper’s own guilt, and what punishment would be appropriate. If the harm caused by McNeil’s repetition of the N-word before two high school students in Peru mandates his firing and public humiliation, the harm that the paper has done 158 times over, in public, before an audience of 4 million subscribers, as well as potentially every person on the planet with access to the internet, numbering perhaps 3 to 4 billion—is incalculable, even genocidal.

Shouldn’t every writer and editor at the Times—starting with Dean Baquet and Joe Kahn, and of course publisher A.G. Sulzberger—resign their jobs, right now? Resign! But first, confess—so that your departure can have meaning, and so that America’s once-greatest newspaper can continue leading us into a future free from hatred, bigotry, want, need, fear, and war, just like in the old Soviet Union.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.