Q&A: Scott Ian

Before the “Big 4” heavy metal show at Yankee Stadium, the Anthrax guitarist and lyricist talks Queens, Jews, and Louis Farrakhan

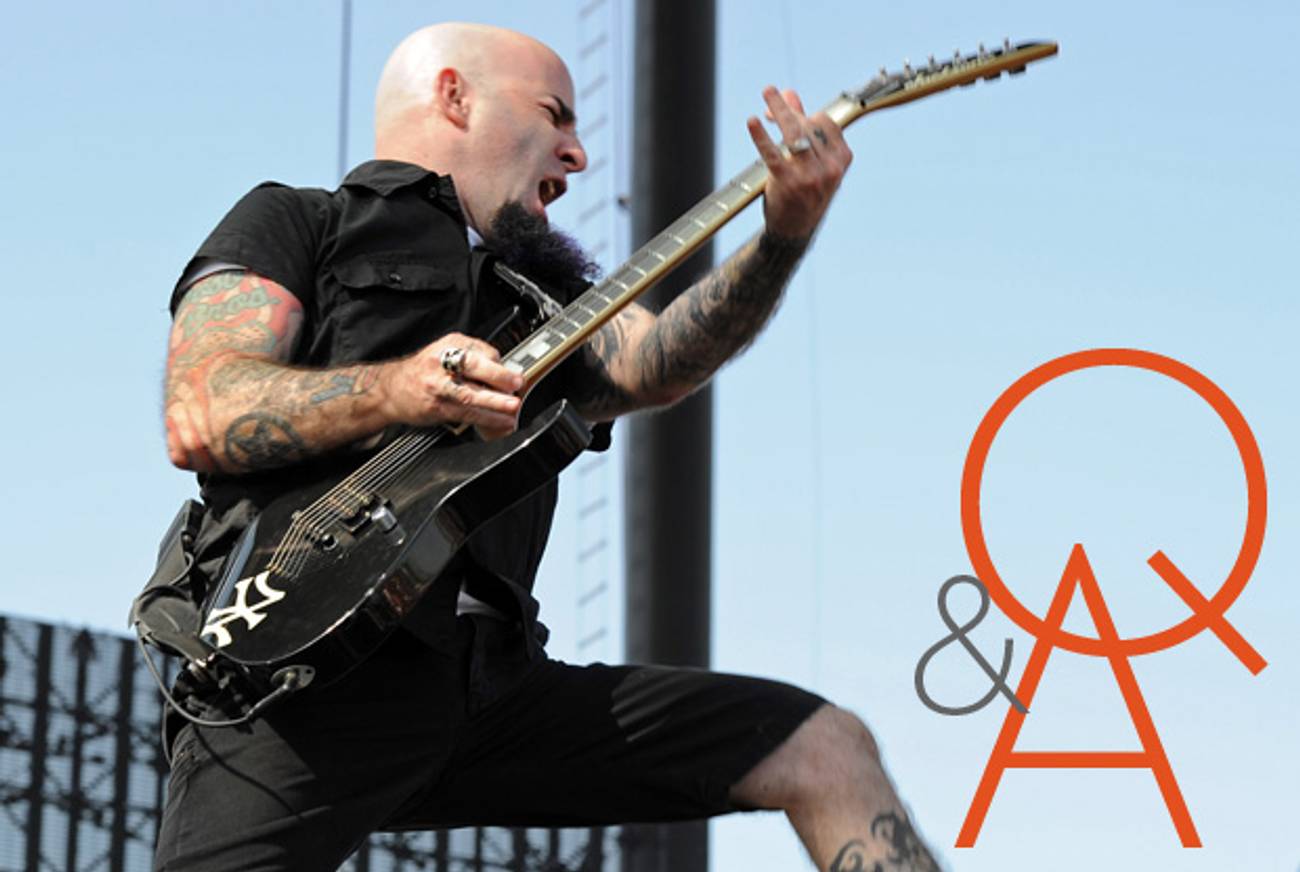

Scott Ian was a 14-year-old kid from Bayside, Queens, when he saw his first KISS show at Madison Square Garden. Now 47, and living in California with his wife Pearl Aday, who is Meat Loaf’s daughter, the rhythm guitarist and primary lyricist for the heavy metal band Anthrax is an energetic little man with an outlandishly long and pointy billy-goat beard that immediately marks him as a stage performer of some kind, or a refugee from a reality show or a circus.

A proud freak and knowing fan, a talented performer, a songwriter and businessman who has sold over 10 million albums of his music worldwide, Ian is a funny mix of brainless extrovert and outer-borough sharpie. Born Scott Ian Rosenfeld, he at first denied that being Jewish meant anything in particular to him growing up. As he tried to solve the riddle of why a Jew from Queens would be attracted to the music of meth addicts and assembly-line workers, he revealed a streak of ethnic pride that helped him explain why the Jew and the metal-head in him are actually the same person.

We met in the lobby of a boutique hotel in the East Village that was made up to resemble a boutique hotel in Los Angeles. We talked for 45 minutes during a round of press interviews leading up to tomorrow night’s “Big 4” concert at Yankee Stadium, featuring four of the biggest metal bands in the world: Slayer, Metallica, Megadeth, and Anthrax.

Tell me about growing up in Bayside, Queens.

I didn’t know anything else. That’s where I lived. I loved it. It was great growing up there. Looking back on it now, even though we were growing up in Queens, it was very Americana, growing up with a pack of kids, Jewish, Italian, and Irish. We all played baseball. We all read comics. We all liked music. I thought it was a great place to grow up.

And your family was Jewish?

Uh-huh.

What did that mean in your family?

Nothing.

Nothing?

No. My parents at that point in time weren’t religious at all. We had a Christmas tree every year. We had a Seder. We had Rosh Hashanah. We’d go to Florida every Passover, to my grandparents’. My grandfather was Orthodox, and he was religious, but neither of my parents were. Of course, as they got older, it seems like they get more religious the older they get, even though they’re still not practicing Jews.

So who’s the better band from Queens: Anthrax or the Ramones?

I will absolutely say that Johnny Ramone was a huge influence on me. I’m a giant Ramones fan. But we couldn’t be more different as far as being a heavy metal band and what the Ramones are about, whether you want to call it a punk band or a rock ’n’ roll band or pop band. They had all of that. We don’t really have much of that. But, yeah, there’s definitely a line through from the Ramones to us because we all listened to the Ramones as kids. I saw them at Queens College in ’79, I think. I remember seeing them on the Sha Na Na TV show when I was a kid and then finding out they were from Forest Hills, which was only six, seven miles away from where I lived. It was just kind of amazing to me because they seemed completely reachable, whereas KISS—even though Gene Simmons’ mom lived a mile from where I lived—seemed completely out of reach, in a different universe. You could never do that.

Because they were too big, they played these huge stages with the tongues and the fire?

Yeah. The image. But the Ramones were just a bunch of dudes in Levis and leather jackets just like I was. So, that to me seemed obviously much more reachable and made the idea of being in a band a lot more real to me. Here were a bunch of dudes I could identify with because we looked the same.

When people think about rock ’n’ roll Jews from New York people think Lou Reed—that’s a Jewish rock ’n’ roll guy. Or the Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in Greenwich Village. But actually, there’s you, the Ramones, and KISS.

The Dictators. People forget about them. Amazing band from the ’70s and early ’80s. They had Dick Manitoba, Ross “The Boss”—a bunch of good old Jewish boys.

You spend a lot of time with Gene Simmons.

Yeah, we’re friends.

So, you see a guy who did what with his life?

He made every possible dream come true. He really did. He came here from Israel with nothing, him and his mother. No money. He created an empire that’s gotta be worth billions of dollars, and that’s pretty amazing considering that when he first moved to America he couldn’t even speak English. He had a thick, thick Israeli accent. That says a lot about his tenacity, his fortitude. He’s always been a role model for me in that sense.

That’s kind of how I feel I’ve been in this band in a lot of ways. It’s entertainment and it’s fun and everything else, but if you don’t handle the business side of things, it’s going to fall apart. Go find a new job. I think KISS is a very good role model looking at it that way. Obviously we’ve never been able to merchandise ourselves the way they do because we don’t have the image and the stuff. But from just meeting those guys over the years and touring with them over the years, you get a good sense of how their operation works and how they do things. You could sit and ask Gene questions for three hours. There’s nothing he loves more than to sit and talk about himself, which works out great for me.

Even though I know him and I’m friends with him, I’m still a sweaty 13-year-old when I’m with him. There’s still that part of me that’s thinking, I can’t believe I’m sitting there talking with Gene Simmons.

Of all the forms where you’d find Jewish musicians, heavy metal would not be the first one I would choose.

Why not? I’m certainly not a practicing Jew. I would never claim, “I’m Jewish.” That’s not the first and foremost thing in my mind, as far as who I am as a person. But I know a lot of Jewish history, of course. And if you take the Jewish history up to the Jewish immigrants coming to New York in the late 1800s and early 1900s, think about just how tough those people had to be, I can relate it to my own history. My grandfather, in 1916 I think it was, his parents had to smuggle him out of his village in Poland because the Germans had occupied it and they were killing all the men in the village. So, they paid people to smuggle him to Amsterdam, where he stowed away on a boat and got to Ellis Island with no papers, so they put him back on a boat. Lucky they didn’t send him back to Poland. They sent him back to Amsterdam, where he worked for six months, eight months, until he had enough money to get proper papers. Some family took him in, gave him a place to sleep. Came back to Ellis Island, this time with papers, went to the Lower East Side, got a job at a grocery store, and within a couple of years, he had his own store on Rockaway. When I think about how tough that was, anytime I complain about anything, it’s easy to think, you know, I don’t have things so bad.

But to answer your question: Jews are tough people. People think of Jews as the Woody Allen stereotype, the nebbishy kind of thing, but that’s not the kind of Jews I know. I know plenty of Israelis and plenty of tough guys that are Jewish. So, I think it makes sense that Jews play metal.

This brings me to the point where you became a hero of mine. When I was a young hip-hop kid, I was really into Public Enemy, because they were the greatest. And they were from here. And then they did “Bring the Noise,” which was on one hand the best song ever. And then it had that Farrakhan line there, “Farrakhan’s a prophet that I think you oughta listen to.” And I was just like, “Oh shit, this makes me sad. I love this band, I love this song, and here they’re promoting this weird, hating creep.” And then you did your cover. And I was like, man, he took this song back from them. Was that in your head at all?

Not at all. Public Enemy became my favorite band as soon as I heard them. I had a bunch of friends that worked at Def Jam back in the eighties. A guy named Scott Koenig, George Drakoulias back in the day. I was friends with Lyor [Cohen]. I knew everybody in the office back then. We used to go to Rick Rubin’s apartment and listen to records all the time, before everything blew up. This is pre-Def Jam becoming Def Jam and Rush becoming Rush.

So, how come Rick produces Metallica and not you guys?

We never asked him to produce us.

You should!

We don’t want Rick Rubin on our records. I love Rick Rubin, I think he’s amazing. I just don’t think he’s the right fit for us. But anyway, I was just a big Public Enemy fan. I got to hear tapes of the first record before it was out. And I remember hearing “Rightstarter” and “Rebel Without a Pause” and just thinking, “Man, this is the heaviest shit I’ve heard in my life. These guys are brutal. They’ve just taken all rap to the next level.” Then I got to meet Chuck and we became friends. I started wearing a Public Enemy shirt all the time on stage. Chuck would see pictures of me wearing it. So, we just became friends back then.

Cut to when they record “Bring the Noise,” and they name-check Anthrax in the song. We were just completely blown away. So, it was kind of like this mutual admiration society. And in the back of my mind I just always wanted to find a way to work together, and I knew there was a way, I just had to figure it out. How could I do something with Chuck D?

It was in 1990 when we recorded Persistence of Time. We were pretty much done with all the drum tracks. And I said to Charlie, “I’ve got this idea to cover ‘Bring the Noise.’ ” I basically transposed the horn part, came up with a guitar riff based around the horn sample that they were using. I said, “Let’s come up with an arrangement.” So, we came up with an arrangement for the song and we tracked it. This was back in the day when there was no Internet, so you couldn’t send an MP3. We made a cassette and sent it in the mail to Chuck.

So, I called him up and said, “Hey, man, we just recorded ‘Bring the Noise’ and we want you and Flav to be on it.” And he said, “Scottie, why don’t we come up with something new, from the ground up? Let’s write something together.” And I said, “Well, let’s do that too. But you gotta hear this.” Because we recorded the track and we were like, “Holy shit, this is sick, this is so heavy. People are going to lose their minds.”

So, it takes three days for him to get the fucking tape. We had already spoken to Rick Rubin. I told Rick what we were doing, because Chuck said, “Why don’t you call Rick and see what he thinks.” So, we spoke to Rick and immediately he says, “I think it’s redundant. They already recorded ‘Bring the Noise.’ Why don’t you do something different?” “I know, I know, but you just gotta hear this, Rick. You just gotta hear it.”

Finally another two days goes by, Chuck gets the tape, calls me back, and says, “Holy shit. This is slamming. When do you need us? When and where?” And that was it. It was as simple as that. They heard the track. They did the vocals. We shot the video in Chicago when we had a day off on the Clash of the Titans tour. On the way back to the hotel from the video shoot, someone on the bus—I think it was our manager at the time, Johnny—made a mention, “You guys should play some dates together.” And Chuck’s like, “Hey, you got my phone number.” World tour was booked like two weeks later. It was all just because we liked working with each other so much.

I just did “Bring the Noise” with them at the Sunset Strip Music Festival two weeks ago in L.A. Eight thousand people out on the street. It’s as magical now as it was in 1991.

And how do you feel about the Farrakhan line?

I never cared. If that was their belief at the time, and they backed Farrakhan, and obviously he had problems with Jewish people—you know, I never spoke to the man myself.

I can’t tell you how many interviews I did back then, in 1991, when people said, “How could you work with Public Enemy? They hate Jews, they hate whites.” And I said, “Well, if they hate Jews and they hate white people, they’re all really great actors because I just spent two months on tour with those guys and we had the best time ever.” Especially Professor Griff, who got the most heat back in the day. He was my best friend on that tour, and even now when I see Griff it’s all hugs and kisses. I’m like, if these guys hate me, they’ve got a good way of not showing it, you know?

Lyor once told me a story about when he was tour manager, when the controversy around Griff erupted, of saying, “Look, you guys may not know what buttons you’re pressing, but I want to show you something.” And he had the Holocaust Museum in Washington closed down and he brought those guys through it. And was like, “I travel with you, we’re friends, you’re going to see this, so you’re going to know what you’re talking about. The next time, if you still want to, go ahead, but this is it, this is the shit.” I think Griff and them then parted ways.

My attitude with it is I never judge anyone until I meet them. And obviously I already knew Chuck, and I never felt for one second that this guy had an evil bone in his body, so what he felt about Farrakhan wasn’t my business. My business was my relationship with Chuck D.

Now tell me about that release of energy on stage and how you prepare yourself to do that and what it feels like afterwards. That’s an insane amount of yourself to put out.

I just stretch. I don’t do much. I do a little bit of stretching. I warm up on the guitar for about 15 minutes. I do as little as possible all day long to save as much energy as possible, basically for the show. Because it is a crazy burst of energy, almost like running sprints. You go from zero to 100. One second you’re standing around doing nothing, and the next second you’re on stage giving every amount of energy you have in your body. At an Anthrax show, there is no really pacing myself. I always try and say I’m going to pace myself, but it’s hard to. It’s just natural for me to get on stage and do what I do. Sometimes, yeah, if I get winded, I get winded. There’s nothing I can do about it. Like I said, from zero to 100 in one second.

Doing that night after night after night, the stamina required for the touring thing, has always astounded me. I know some great musicians and they can’t do it. They can play at home, they can play in a studio, but to have to do that for two months, three months, it’s too draining.

We’re still able to play five nights a week. But it’s hard. Physically it definitely takes a toll. I’m waiting for the day when I’m going to need hip replacement, probably knee surgery—all that stuff I’m sure is in my future. Just like athletes. The damage I’ve been doing to my body since 1981 is, I’m sure, going to come back and bite me in the ass. All the headbanging—I’m going to be like one of those old guys walking on the street hunched over like this.

An old Jewish guy.

I look at AC/DC as my touchstone for it. Because Angus is 10 years older than me, and he’s still out there doing it at the level he does it. I always felt like, whatever Angus does, I have to do at least that much. And they’re still out there destroying. I figure we’ve got at least 10 more years.

How much time do you spend in New York now?

I’m here enough to not miss it. Let’s put it that way. I wouldn’t want to live here anymore. I like the lifestyle much better in California. It’s a lot quieter. I live up in the mountains, out by the ocean. I don’t want to say where. Obviously I love New York. I’m here, I don’t know, six times a year usually. At least.

I grew up in the ’70s and ’80s, and New York was a hardcore place then, and now it’s a very, very different city.

Oh, it’s changed. It was the Giuliani years that changed the city for me. It was when he came in that, for better or worse, he cleaned up the city. And then Bloomberg has obviously just kind of kept on that path of making this the playground of the rich. Which I’m not saying is a bad thing, because the city is certainly safer than it was when I was a kid. And it’s an amazing place to come to. Part of me does miss the grit that used to exist here. You know, you can go as far as you want in the East Village these days and not worry about it. When I was a kid, the thought of going to Avenue A meant you were going to get stabbed.

It was fucking scary!

Yeah. Avenue A meant stabbed. Avenue B meant shot. Avenue C was decapitated. That’s how we used to think. And it was true. You only went there if you were looking to buy heroin. Or get killed. Now you can go to Avenue B and spend $2 million on an apartment, so things certainly have changed.

It’s easy to imagine your music coming from a city where I grew up and it’s hard to imagine it coming from here.

Well, that’s the difference between us and the Strokes. Our music sounds the way it does for a reason and their music sounds the way it does for a reason. It’s when you came from New York. And that’s not a diss on the Strokes. I’m just saying, they come from a New York City that was able to create that band. That band wouldn’t have come out of New York City when we came out of New York City.

There was an early Stormtroopers of Death song—

Strokes are a bunch of Jewish guys too, aren’t they?

Yeah, some of them, I think. There was an early Stormtroopers of Death song, “Fuck the Middle East.”

Pro-Israel song.

A pro-Israel song.

Pro-Israel and -Egypt.

It sounded like my Uncle Myron being mad at the dinner table. Tell me about that song.

I can’t tell you specifically about what was going on at that time politically—’84, ’85. I know that there was a lot of crap going on. If I think about the lyrics, Syria, Iran, Iraq—we’re talking about all those countries that, what, 26 years later are even worse. Nothing got better in any of those places. So, maybe if they would’ve listened to S.O.D. in 1985 and like we said, “flushed the bastards down the can,” the world would’ve been a better place. But 26 years later, it’s even worse. Nothing’s gotten better in Syria. Well, maybe Lebanon’s gotten better.

They were really killing each other there.

Yeah, the political climate in Lebanon has gotten much better. But obviously Syria, Iran, Iraq, it’s all still a fucking mess. They should’ve listened to us. We had all the answers.

Now is there going to be a joint KISS-Anthrax show in Israel? You guys should do that.

I wish. We’ve tried to play Israel. It’s been on the schedule a couple of times, I think it was twice. But both times we haven’t been able to go because something was going on politically or whatever and we were told, “It’s not a good time to bring you over. We’ll figure it out another time.” And Metallica’s been there, Megadeth’s been there. So many of my friends’ bands have been there. We’re like the only one that hasn’t been there. So, I’m jealous, and really eager to get to play there.

Now tell me about this show on Wednesday night. You’ve got four of the biggest metal bands in the world in one place. The Bronx is going to disintegrate.

I hope so. I hope this show makes front-page news all around the world. Not necessarily for anything bad happening.

Not necessarily. But.

Well, I don’t want anyone to get hurt. I just hope it’s crazy.

That’s a lot of energy to have in one place.

But look, it wouldn’t be any worse than a rowdy Yankees crowd coming after a big post-season game and going nuts to celebrate. But Yankee Stadium is different now, let’s just say.

It’s not the Yankee Stadium of our youth where they threw D batteries at the opposing players.

I remember that day where they gave out proper, full-on, Louisville Sluggers. The real baseball bats that dudes were using. I still have the Thurmon Munson bat, which was his actual weight and size bat, that I got in the ’70s at Bat Day. Then they went from real full-size, real baseball bats to those little miniature bats, and from that to no more Bat Day because people were just beating the shit out of each other with these bats in the stands.

Yankee Stadium today is full of investment bankers. They’re not going to hurt anybody.

Except for the bleachers. The bleacher creatures. It’s still pretty fun out there. Anywhere else in the stadium you could probably get away with wearing Red Sox colors, except for the bleachers you’ll get doused and thrown out, as you should.

Absolutely. And tell me stuff that you’re going to do in the city, anything that you look forward to.

This trip we’re just doing promotion all week. You know, I’m here to work. I get it. I’d rather be out with my wife and kid walking around the city all day, but I’m working. But at night, it’s mostly about eating. Just going out to places that I love to eat. Seeing friends. My dad’s coming tonight after work. He hasn’t really met my son yet. I have an 11-week-old.

Your dad, what does he do? He still works?

He’s in the jewelry business. What else would he be doing?

In Manhattan? He’s got one of those little offices with the security doors?

Well, the office does. He actually found a really good niche for himself. He’s in the pearl business, and he basically goes out on these cruises from Hawaii to Tahiti to New Zealand like four times a year and works on the boat, selling pearls for this company. So, it’s better than sitting in a cubicle on 47th Street.

David Samuels is most recently the author of Seul l’Amour Peut Te Briser le Coeur, a collection of his writing about America, to be published in September by Seuil.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.