Rabbi Threatens Landmarked Shul

The leader of a historic Lower East Side synagogue wants to tear it down to build luxury condos

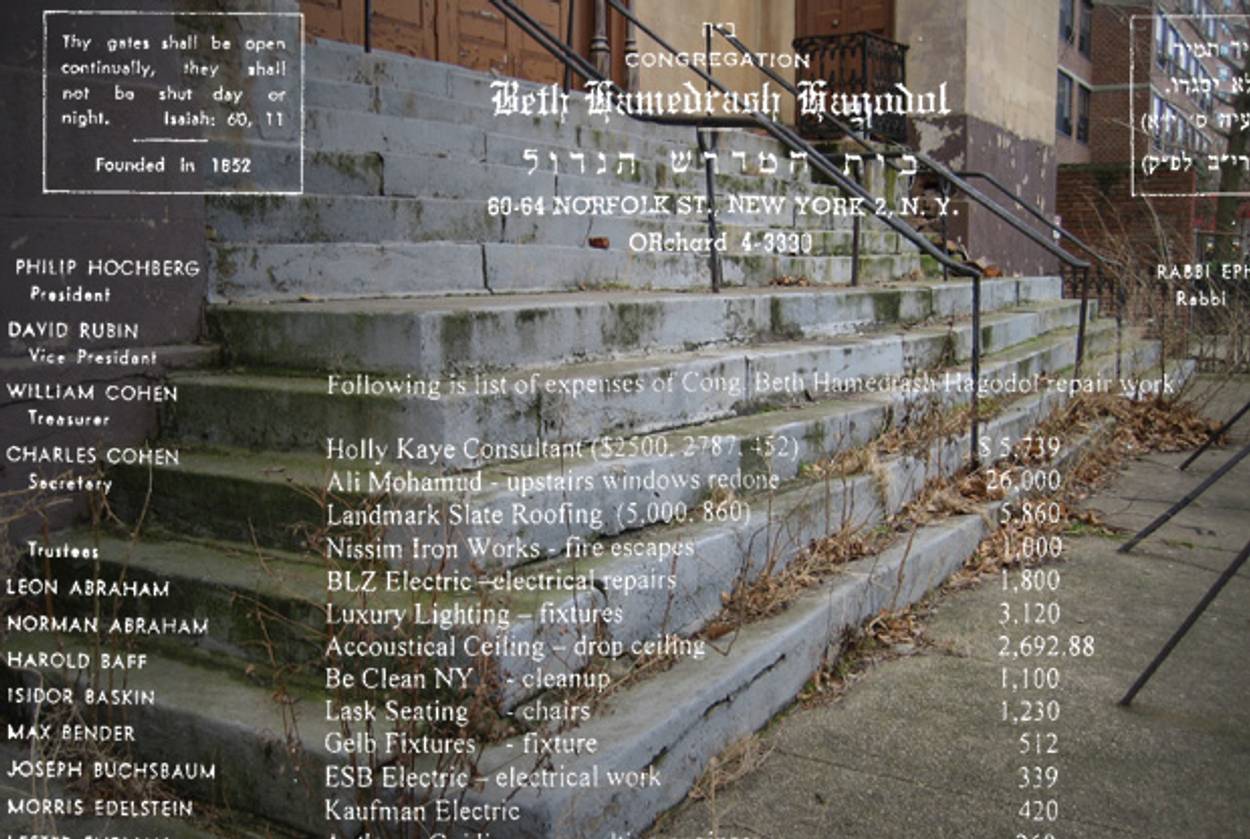

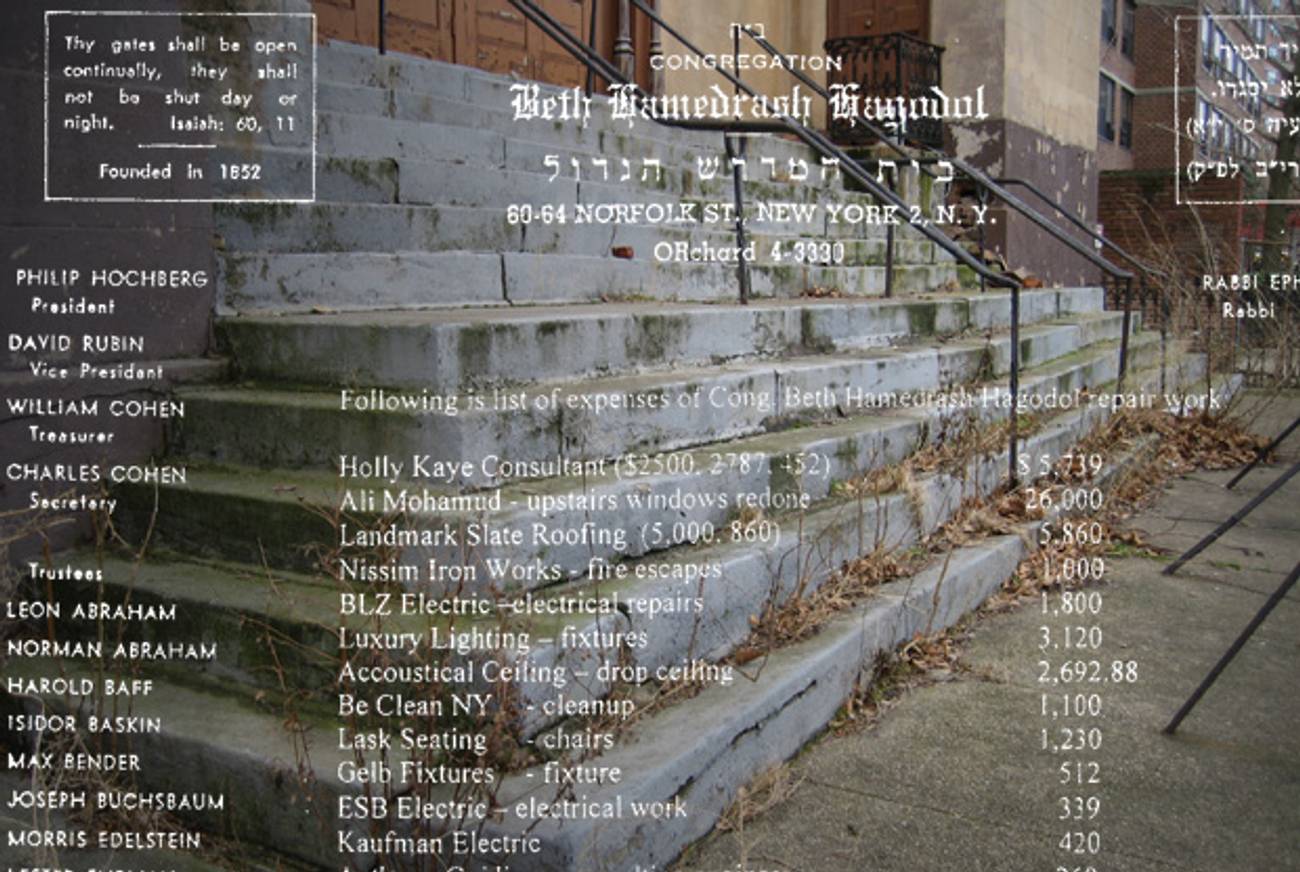

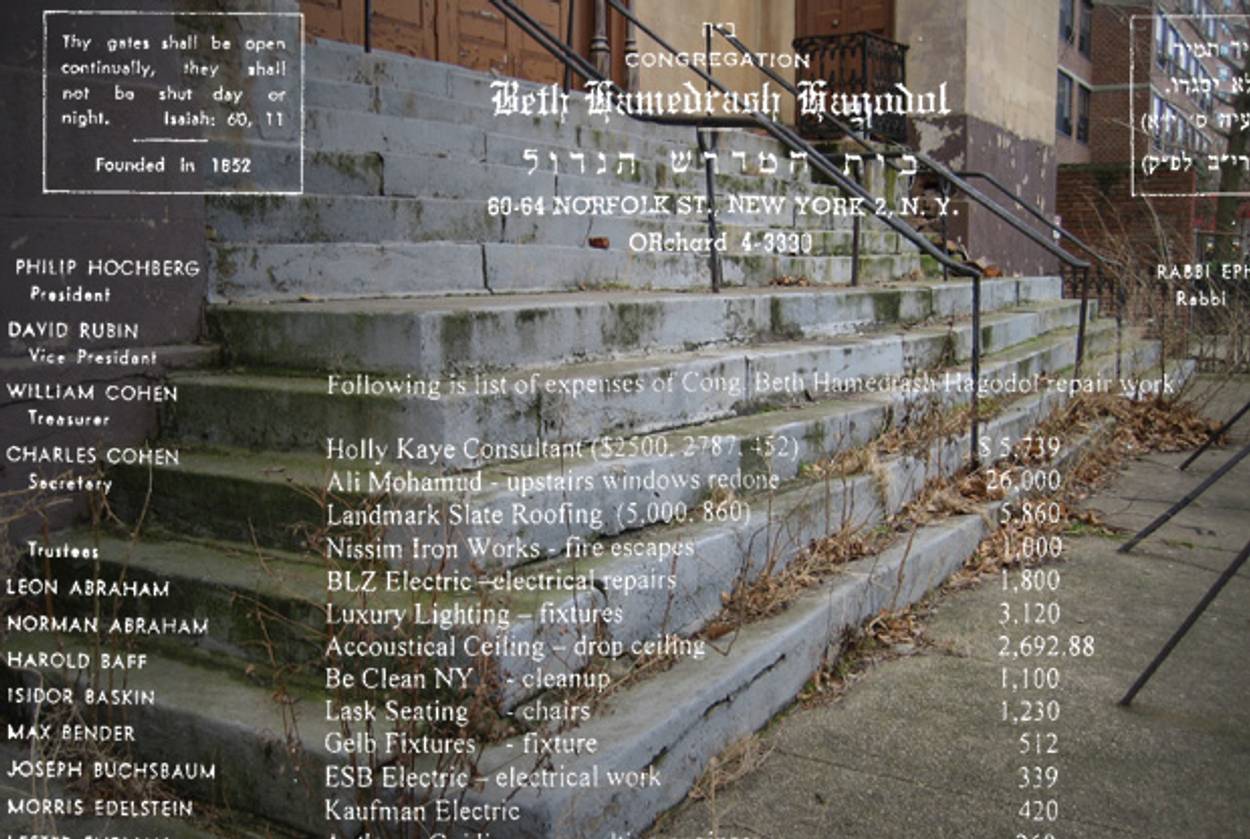

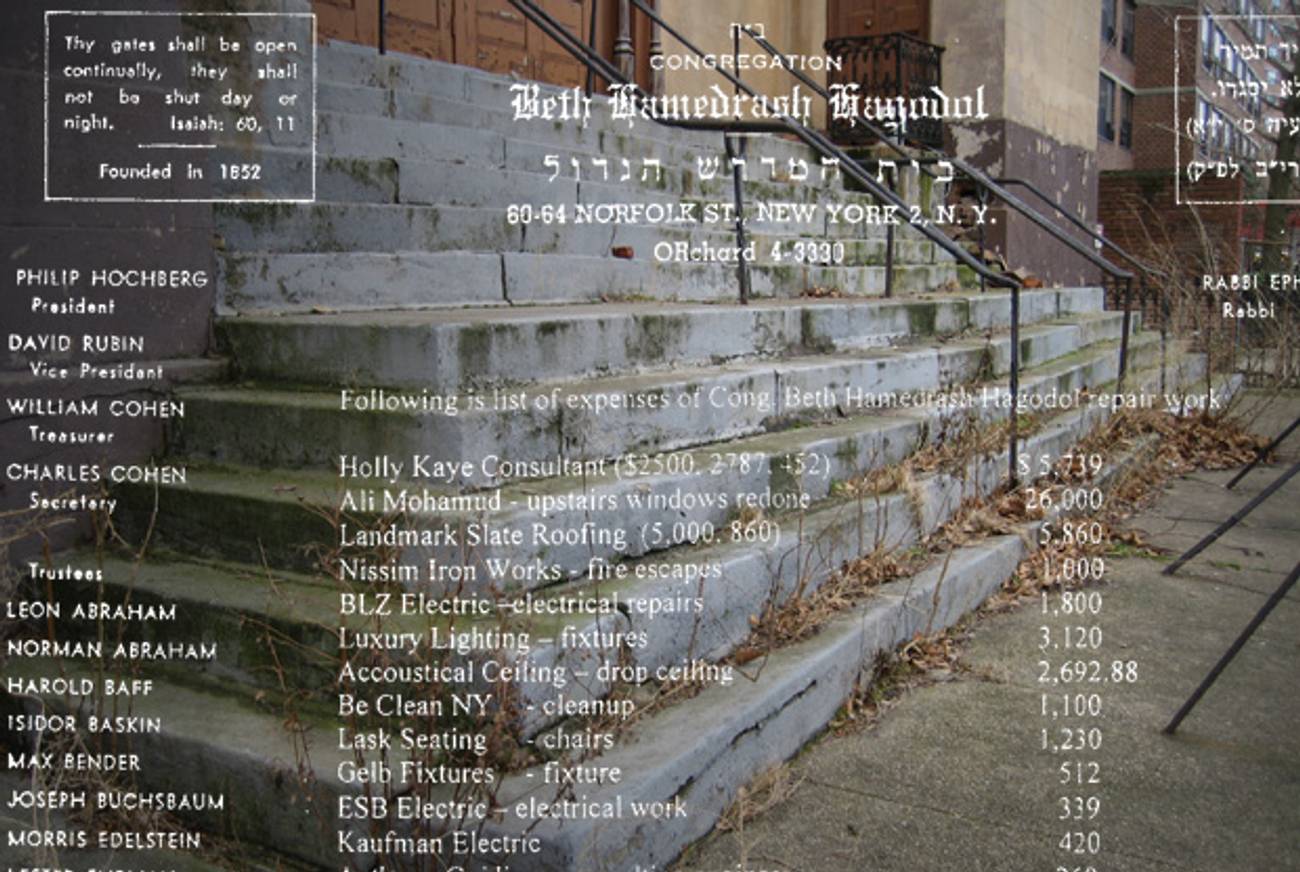

The Beth Hamedrash Hagadol synagogue on Norfolk Street, widely recognized as an irreplaceable part of the architectural and social fabric of the Jewish world of New York’s Lower East Side, and officially designated as a historic landmark in 1967, is now under threat of being torn down—by its own rabbi. Tablet has learned that the synagogue, which is home to the oldest community of Orthodox Russian Jews in America, was recently targeted by a so-called hardship application to be demolished, submitted by Rabbi Mendel Greenbaum, the current rabbi of the congregation. Such an application is a necessary procedural step when tearing down a historic-landmarked building. According to the application, Greenbaum is seeking permission to demolish the historic building and replace it with a new structure consisting of “a replacement synagogue within a residential building.”

Elisabeth de Bourbon, director of communications at the city’s Landmark Preservation Commission, confirms receipt of the request and says a public hearing will be scheduled once the application has been reviewed. While only 16 hardship applications have ever been reviewed by the commission, fully 13 of them have been granted.

Replete with flying buttresses and peaked windows, the historic Gothic Revival structure was built in 1850 and purchased by the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol congregation in 1885 for $45,000 (about $1.2 million today). In evaluating the building’s importance, the New York City Landmarks Commission found that “Beth Hamedrash Hagadol Synagogue has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest, and value as part of the development, heritage and cultural characteristics of New York City.” The Landmark Preservation Commission was further impressed by the building’s “austere simplicity.”

The century-and-a-half-old congregation housed in the building has a deep and significant history of its own. Its second rabbi, Rabbi Jacob Joseph, was the only chief rabbi in New York City’s history (the position was dissolved after six years). After World War II, the shul was led by Rabbi Ephraim Oshry. One of the few poskim to survive the Holocaust, Oshry spent the war in the Kovno Ghetto where he wrote responsa to Jewish legal questions that arose from the gothic circumstances of the ghettos and concentration camps, such as whether, according to Jewish law, a Jew could say Kaddish for a gentile woman who hid him from the Nazis (he may and must—it is a mitzvah), or whether a Jew could commit suicide in order to avoid witnessing his wife and children being killed (he may not), or whether it is considered desecration of the dead to perform a Caesarean on a Jewish woman who had been shot for disobeying the law against Jews procreating (it is not). Oshry buried the responsa in a tin can and retrieved them after the war, publishing them and winning the National Jewish Book Award. Oshry, who passed away in 2003, is remembered by those who knew him as something of a legend, equal parts heroic and witty; “He dug his own grave nine times,” one observer told me. Oshry used to jokingly refer to the ghetto dwellers as “dead men on vacation.”

It was Oshry who applied in 1967 for the landmark designation, which was awarded just two years after the Landmark Preservation Commission was established, making it one of the first buildings to receive the honor. The Landmark Preservation has its own politics, Esther Malka Boyarin, a doctoral candidate in geography who engages in advocacy for historic Lower East Side buildings, explained to me. According to Boyarin, the Landmark Preservation Commission “mainly landmarks brownstones, or Federal, Beaux Art, and Art Deco buildings,” like the New York Public Library—not buildings with “vernacular architecture”—the signature immigrant practice of mixing styles. The Beth Hamedrash Hagadol is in the vernacular style. “You have to imagine what it was like for this Eastern European Jew to go to the Landmark Preservation Commission. The story goes, they told him about the urban renewal plans for the Lower East Side, and Oshry said, ‘How do I stop it?’ And they said, ‘If you get the building landmarked, they can’t destroy it.’ He was a real okshon,” or strong minded, Boyarin said affectionately.

It is hard to imagine how Oshry might respond to the news that the synagogue he saved after escaping the Holocaust was again being threatened with destruction—this time by his successor, who, in yet another twist to this painful story, happens to be his own son-in-law.

***

The congregation on Norfolk Street has shrunk significantly from its peak at the turn of the last century when it had over 1,400 members. In 1990, only 65 members were on the books. By 2006, member rolls showed only 35; in 2012—only 24. As the congregation dwindled, the building dilapidated. In 1997, a storm blew out the two-story front window. An electrical fire in 2001 caused significant damage. The roof became unstable. In 2007, Greenbaum closed the doors, and in 2011, the DOB declared a vacate order, according to Department of Building documents. Now chunks of plaster lie on the dusty and molding blue velvet cushions along the benches. One quarter of the gallery has collapsed into the sanctuary. The plaster is peeling back from the walls, exposing the brick exterior walls, and the floor of the sanctuary has begun to sink into the basement.

Yet there are people who suggest that many of the synagogue’s wounds may have been deliberately inflicted by its own management as part of a larger strategy to tear down the building. Holly Kaye, a planning and development consultant for community-based nonprofits, is the founder and executive director of The Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy, an organization that Kaye says has two main goals: providing support for the historic synagogues of the LES by bringing in professional expertise for funding and restoration efforts, and showcasing the neighborhood. The conservancy became “the secular face of the synagogue,” Kaye says. She remembers Rabbi Oshry fondly as a man who stood four-feet-nine-inches tall and always spoke to her in Yiddish, “unless we were discussing money; then his English was quite good.”

Kaye has been involved in restoring and assisting the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol for the past 15 years. In 1998, when the storm blew out the main window, she organized a $5,000 grant from the Landmark Commission to pay for the window. In 2000, she managed to raise an additional $40,000 for emergency repairs from the state. She then applied for and received a $230,000 matching grant from the Parks and Recreation Department to restore the roof in a way consistent with preservation methodology. In need of a donor to match the funds to use them, she petitioned for the shul to become a National Trust, which got her national recognition and, most crucially, the recognition of a Washington philanthropist named Milton Gottesman. When Gottesman flew out to see the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol, Kaye recalls the “A-ha moment”—“I was standing in the shul with Gottesman, Rabbi Oshry, the rabbi’s son, and his son-in-law Greenbaum, when Gottesman asked us, ‘Well, if I give you the money to restore it, will there be a congregation here in five years?’ ”

It was then that Kaye began to think of the building as separate, and separable, from the dwindling congregation it housed. “We said the congregation could really fit into the beit midrash in the basement. And suddenly, we were brainstorming about what could be made out of the sanctuary.” They came up with a plan: a multi-use cultural space that would occupy the sanctuary and the balcony fully with museum-like exhibits and an educational curriculum.

In the middle of the planning process, Oshry passed away, and his son-in-law became the rabbi of the congregation. Greenbaum had married Oshry’s youngest daughter. “He was 50 when he had my wife,” Greenbaum told me. “By the time we got married, he was not a young man. My wife, she wanted to help out, and he needed someone also to help him. It was an honor for me—he was a very special man. A very special man,” Greenbaum repeated, with a soft smile. By his own account, Greenbaum ended up spending most Shabbats with his in-laws and became involved with the shul.

But how did Greenbaum, a son-in-law, come to be the rabbi, even though Oshry has sons? There are rumors that Oshry’s sons didn’t want a shul on the Lower East Side with a dwindling membership. There are also rumors that the surviving members of the congregation specifically asked for Greenbaum, due to his involvement, and then there are other rumors that hold it was Oshry’s deathbed wish that Greenbaum take the torch. “Rabbi Oshry thought, he is the one,” said Rabbi Aron Mendel, a board member of Beth Hamedrash Hagadol. “He was looking for someone who was a go-getter, who would get the money for the shul. You have to understand, Greenbaum was so involved. The shul was his life.”

Kaye doesn’t entirely dispute Mendel’s assessment. “Rabbi Greenbaum seemed to have a lot of energy,” Kaye said, “and at first we were going along in the same effective way.” Kaye managed to get another grant from a Washington Heights woman named Seigelbaum who left them $250,000 in her will, part of a philanthropic gesture to several LES shuls. Then in 2005 she got New York City Councilwoman Christine Quinn, the Department of Cultural Affairs, and the Borough President’s office to visit and to allocate another $750,000. With the original $230,000, she was now up to $1.25 million. Then she got another $100,000 from the insurance company. Things were looking good.

‘If I give you the money to restore it, will there be a congregation here in five years?’

But just as the ledgers seemed to be rebalancing, Kaye said, things began to change. “Around 2006 to 2007, the rabbi decided to take an independent path without asking our advice as partners,” Kaye said. “He suddenly started to shop around the building.” Kaye said he held up their ability to receive the money they had raised. In order to collect the city money, Greenbaum had to create a secular nonprofit organization. “This process can take as little as a week in emergency circumstances,” Kaye said. “It took him two years.” By then it was 2008, and due to the fiscal crisis, all unspent state funds were withdrawn, and the synagogue lost the $750,000, according to both Kaye and Greenbaum. Greenbaum then refused the $230,000 matching grant. “Then he stopped doing any routine maintenance: no gutter cleaning, no boiler maintenance,” Kaye related. “That seriously undermined the structure.” Greenbaum disagreed: “Totally untrue,” he said. “We tried to clean it, even after we were closed, at least for a couple of years. We cleaned the gutters, whatever we could. Certainly until 2009, we were still maintaining with the upkeep.” In 2006, Greenbaum produced an engineering report declaring the building unsafe, even though Kaye’s independent report claimed most of the shul to be fine. “He seemed to want to close the building,” Kaye said.

But Greenbaum tells a very different story about the past seven years. “Do you know how long it takes the IRS to approve a new nonprofit, after 9/11?” he asked, in response to what Kaye called his delay tactics. “Yes, I refused the money. It was a matching grant. I had nothing to match it with,” he said to the second accusation. “In 2007, I pushed away developers because I was working with the conservancy. I only refused money I couldn’t use.”

Greenbaum said that the Jewish Conservancy paid $215,000 for an architectural firm to assess the restoration costs. They came up with a figure: $3 million. “So what am I going to do with $230,000?” Greenbaum asked. “What do you think, I woke up—boom!—let’s demolish? You think it didn’t hurt me to do this? It hurt me. It kills me that this should happen on my watch. I finally decided, if I can’t have Beis Medrish Hagudl in thatbuilding,” Greenbaum said, pronouncing the name in the Yiddish, “at least we should have Beis Medrish Hagudl. People should know, there’s a shul on Norfolk Street.”

Greenbaum said that his plan is to demolish the historic synagogue building and then sell the plot to a developer who would create a space and a trust for a kollel of 15 to 20 people, to be named “Kollel Jacob Joseph” after the chief rabbi. (Greenbaum did not disclose the prospective membership of his proposed kollel to me during our interview.) When asked if he would consider a coalition with other Jewish organizations, he said with a smile, “It depends who are the Machatonim,” referring to a special in-law family relationship. “Someone says, I want to give you $5 million, let’s sit down and talk! But I don’t want to go here, to go there, to this rich guy, that rich guy, and then we start all over again in three years.”

***

Why would anyone want to tear down a historic house of worship? There is Greenbaum’s stated interest in starting a kollel to be funded in perpetuity by a wealthy real-estate developer. Other interpretations on the Lower East Side range from the cynical to the very, very cynical. Joyce Mendelsohn, author of The Lower East Side Remembered and Revisited and an active member of Friends of the Lower East Side, an advocacy group dedicated to “preserving the architectural and cultural heritage of this rapidly gentrifying neighborhood in lower Manhattan,” sees a parallel in other histories in the area. Mendelsohn’s passion for the LES comes from being the granddaughter of immigrants who “came to the Lower East Side and never left,” she said. She is worried about losing the links to the past that historic buildings represent. “They are erasing memories, in exchange for luxury condos,” she said.

Mendelsohn relayed the disheartening tale of another historic shul in the neighborhood, the First Roumanian-American Synagogue on Rivington Street, whose Rabbi Spiegel was reportedly offered a grant for repairs as early as 1997; “He said, ‘I’m not going to let the government tell me what to do with my building,’ ” Mendelsohn said. Though the matter is still disputed, Spiegel may have refused a later grant of $230,000, which was for roof repairs, and then in 2006, the roof collapsed, and the building was promptly demolished.

Kaye worked on the First Roumanian-American Synagogue through the Jewish Conservancy and supplied the final, chilling detail: “A week after it was demolished, we saw it on a Brooklyn website. It was listed for $15 million. The community was so upset. It gave a very different picture of what was going on.”

But why now, when the Lower East Side has been gentrifying for the past 15 years or more? For starters, a new wave of gentrification is likely to hit the neighborhood, spurred by the development of the largest tract of city-owned land south of 96th Street in Manhattan. “After 45 years of stalling, the Seward Park Urban Renewal (SPURA) is finally going through,” Kaye said. For years, the city equivocated on the SPURA site, which consists of five city-owned plots, unsure of the LES’s readiness for mixed-income housing. But in October, the city formally approved the SPURA development. The five plots in question are adjacent to the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol, making the property even more attractive to developers than it was before.

“SPURA will greatly change the neighborhood,” said Sofia Lewitt, a resident of the Lower East Side and daughter of famous Jewish artist Sol Lewitt. The 29-year-old Lewitt co-owns the Essex Street building she lives in and is engaged in local activist and advocacy groups. “There has been and will continue to be a demographic shift in this neighborhood,” she said. “You have things like Grumpy’s Coffee replacing establishments like Weinfeld’s skullcap manufacturers and Gertel’s Bakery. It’s hard to see all that Jewish identity go.”

But she argues it doesn’t have to go. Lewitt was upset by the hardship application, which she said claimed that there was “no religious community” in the area. “I’m not the most religious,” she said, “but I am a Jew.” Indeed, Lewitt got involved with trying to save the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol after she met the director of Chabad of the Lower East Side, Rabbi Yisroel Stone, on the street one Shabbat. “He says Shabbat Shalom to everyone he sees, and the first person who says it back, he stops and talks to you,” she said. The Chabad has no space of their own—they pray at the Blue Moon Hotel—and Lewitt became active in their search for a house of worship, researching buildings in the area. That’s how she learned about the empty shul on Norfolk Street. “We have high hopes to put Rabbi Stone there,” she said, calling him “very charismatic.” Lewitt believes that if the money could be found, a coalition could be formed that would enable Chabad to use the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol. “I think Rabbi Stone is the future of the Lower East Side,” she said.

Stone declined to speak about the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol for what he called “political reasons,” but he said he has a thriving and growing community with 35 regular members every Shabbat. He also said that, “not having a space is holding us back. If it’s a question of money, any money can be found if you look for it.”

Greenbaum said that he knows Stone is doing good work, and he would be happy to lend him the space when he needs it. His only stipulation is that the space should be used for Orthodox functions, or other “mechubedike”—respectable—purposes.

“There’s no congregation,” I heard over and over from restoration advocates for Beth Hamedrash Hagadol. But there is still a board, whose members appear to largely believe what Greenbaum believes. “The congregation is more important than the building as it is right now,” said Pinchas Jungreiss, a resident of the Lower East Side and a member of the board of Beth Hamedrash Hagadol. “The building is decaying. They tried to raise the money and they couldn’t. You’re talking hypothetical, I’m talking reality!” he admonished me when I tried to ask about donors and restoration plans.

The building certainly needs a lot of work. If it wasn’t unsafe when Greenbaum declared it so (he declined to provide me with the document he submitted), it certainly is unsafe now. But despite the decay and mess inside, the light that comes through the broken window (through which birds fly in and die on the synagogue’s floor) is magnificent. The Gothic Revival architecture, vernacularized though it may be, invokes the sublime heights to which prayers aspire.

The conflict has not diminished a sense of respect on both sides and for both sides. Greenbaum speaks of the preservationists with respect, notwithstanding accusations that he is trying to profit from the destruction of a historic shul. The preservationists who know Greenbaum speak of him affectionately, even when accusing him of misconduct. After I spoke to Kaye and Mendelsohn, Laurie Tobias Cohen, the executive director of the Jewish Conservancy, was told by those “on high” not to speak about the building. Then I got a call from Greenbaum. He had just come from a two-hour meeting with Kaye, in which withdrawing or suspending the application for demolition and hardship was put on the table. Moving the kollel to Brooklyn was suddenly an option, he seemed to be suggesting.

Preserving a historic synagogue in the cradle of Jewish Manhattan while Greenbaum and his kollel relocate to Brooklyn sounds like the kind of solution that all sides might be able to profitably agree on.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.