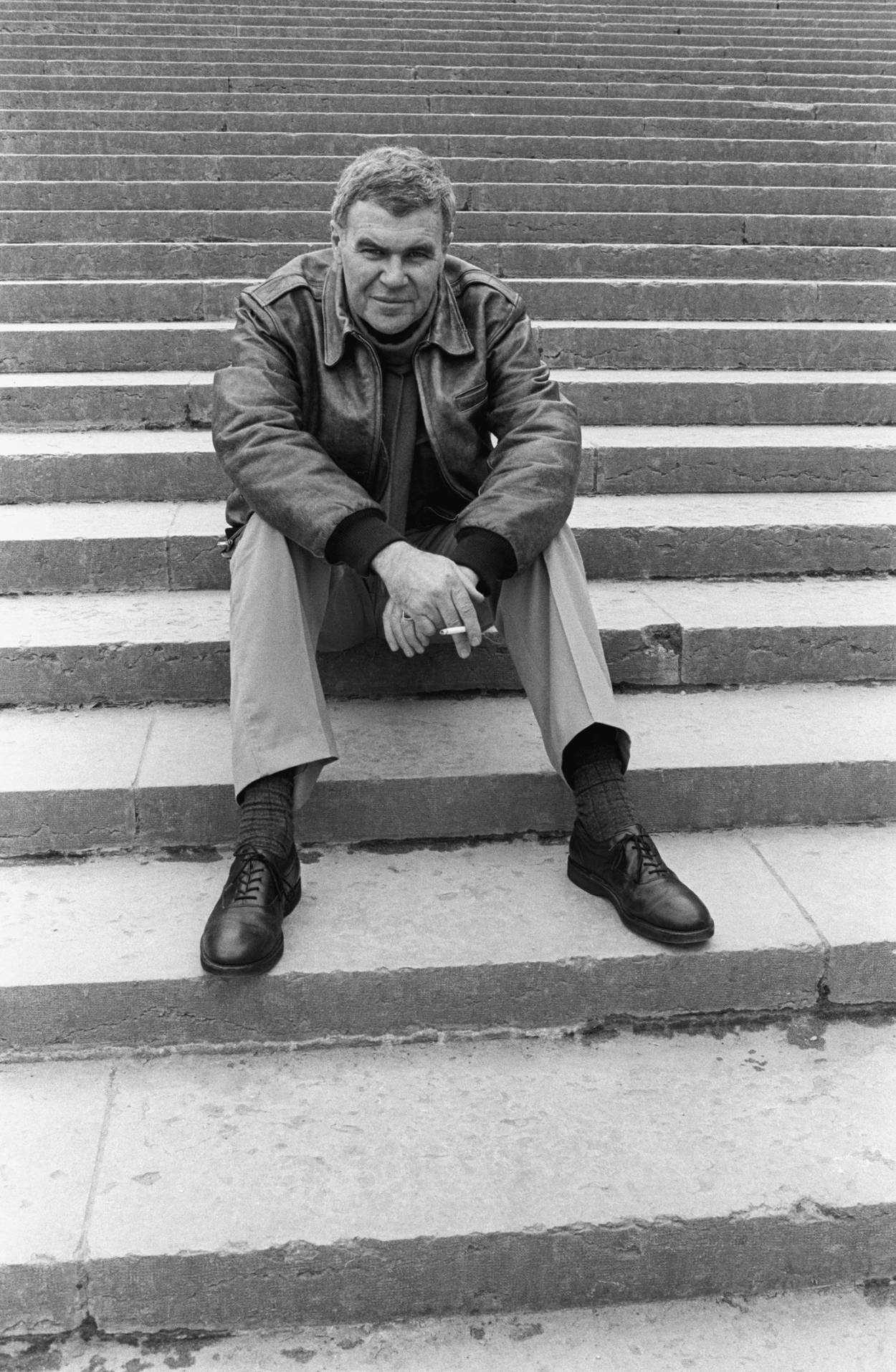

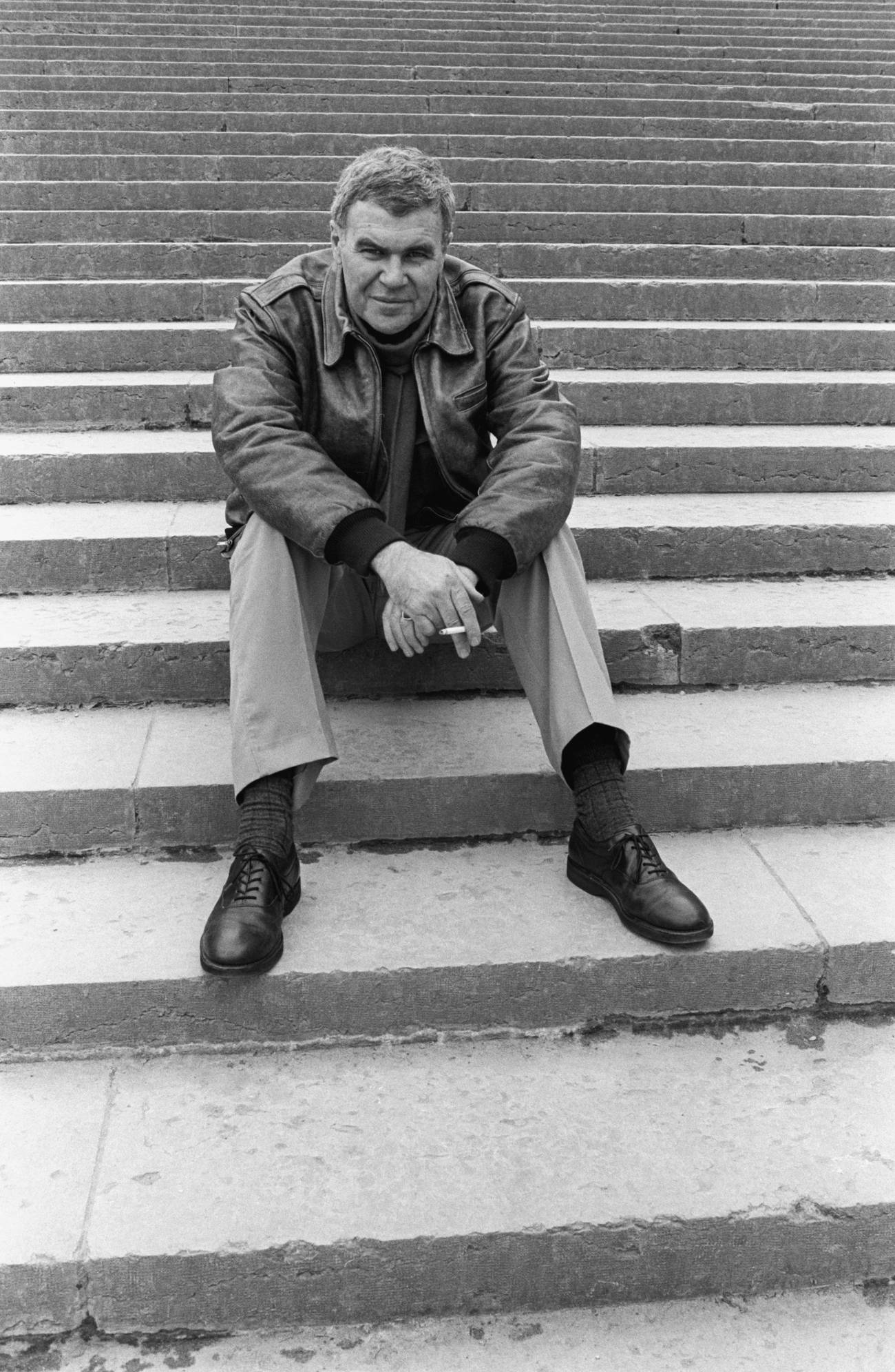

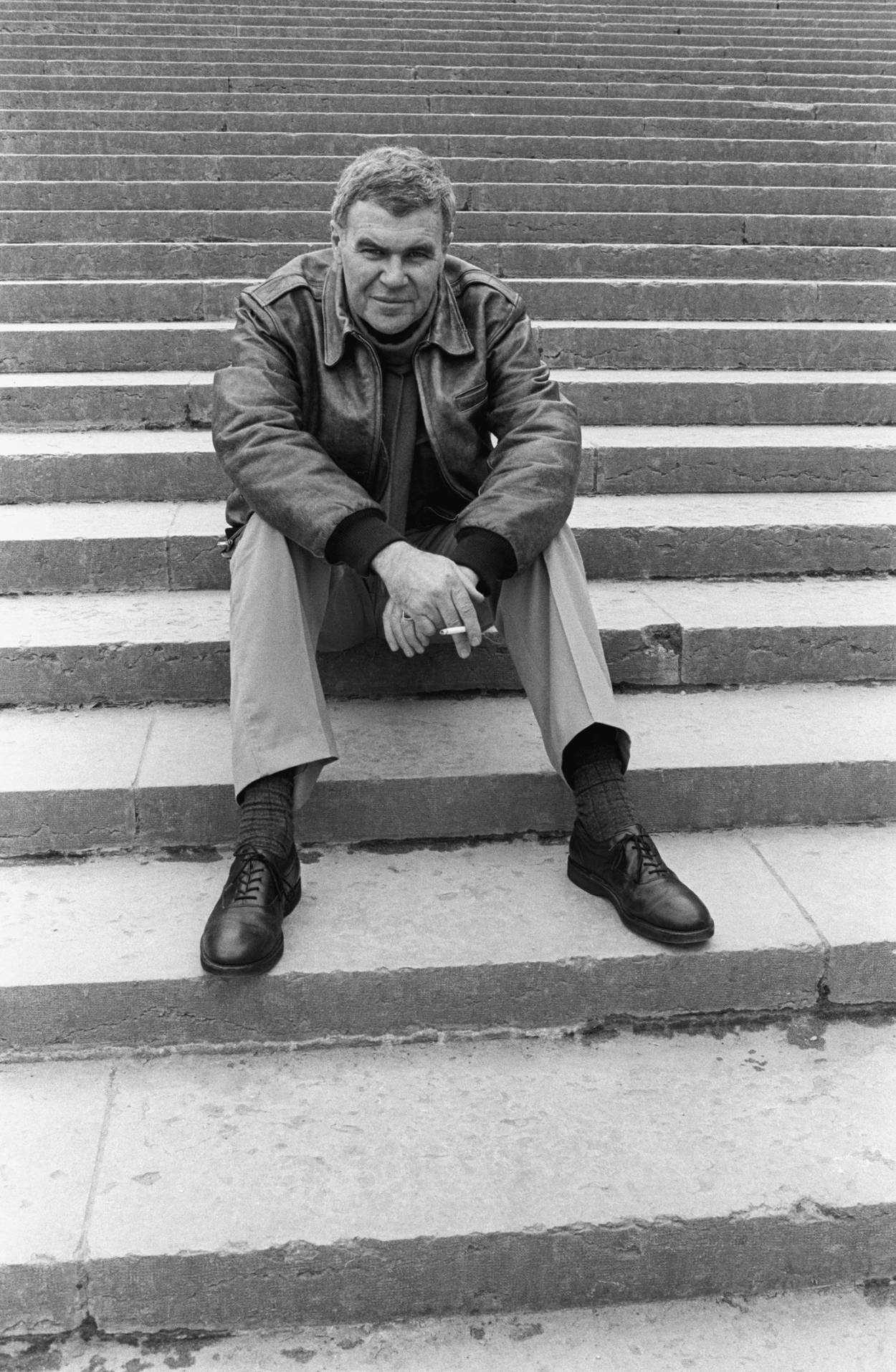

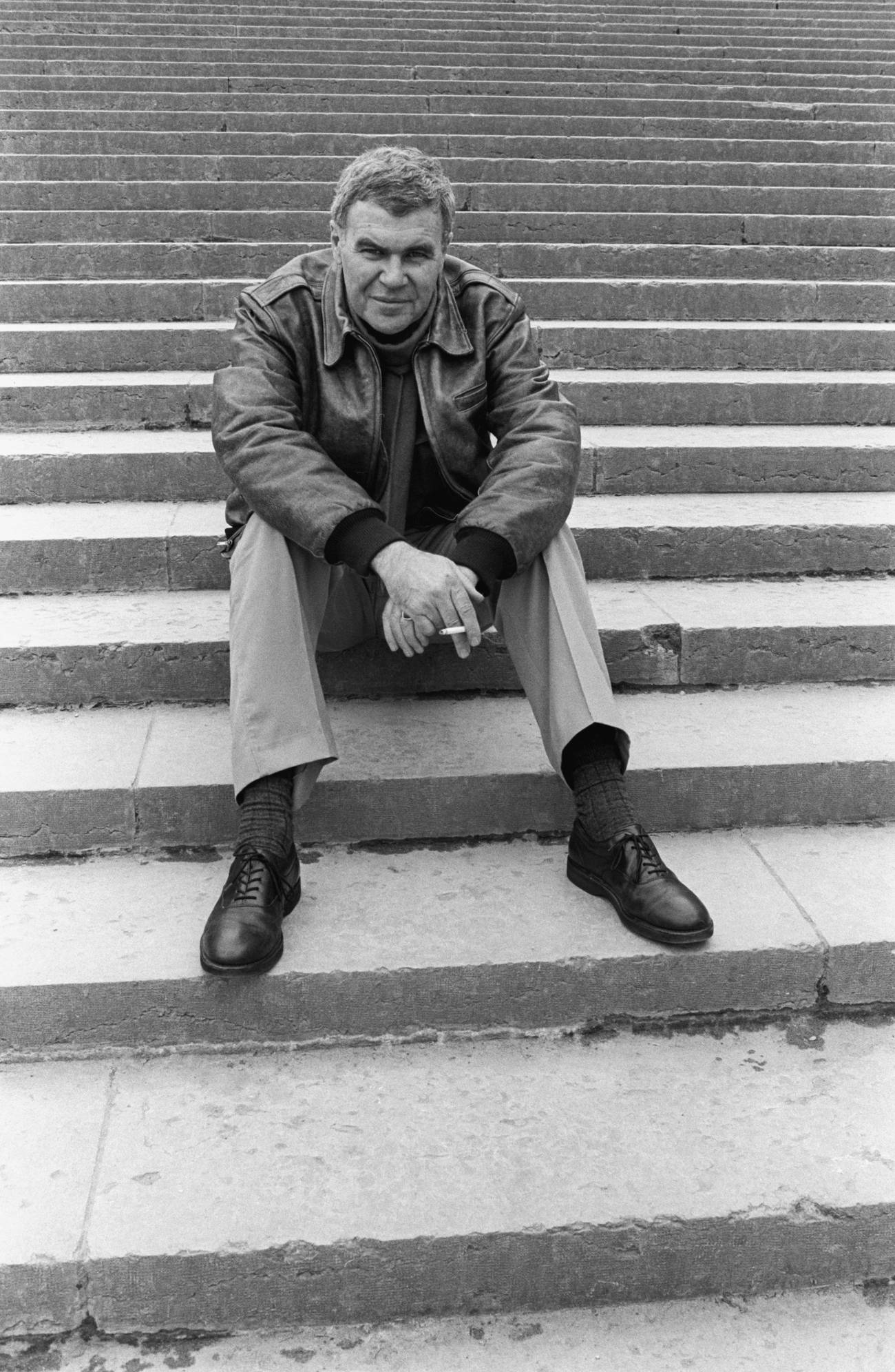

Raymond Carver, Israeli Writer

Though the great American storyteller never felt at home during his months in Tel Aviv, Israelis saw themselves in his direct sensibility

“Is there an American writer more goyish than Raymond Carver?” That was the response of a colleague when I mentioned that I was writing an article about Carver, Jews, and Israel. “What are you going to write about?” she said, “Carver eating bagels with his editor in Manhattan?”

I could see her point. There are no Jewish characters or Jewish settings in Carver’s powerful stories, and no mention of Israel. Jewish readers of Carver’s essays, poems, and short stories know that his work is very distant from American Jewish sensibilities and concerns, and from Israeli realities. Some have described Carver’s fictional territory as “underclass America.” A 1984 New York Times Magazine article called Carver “a Chronicler of Blue-Collar Despair.” The article’s author, Bruce Weber, wrote that “Carver’s stories are populated by characters who live in America’s shoddy enclaves of convenience products and conventionality—people who shop at Kwik-Mart and who live in saltbox houses or quickly built apartment complexes.” This is hardly a description of Jewish Americans in the last quarter of the 20th century.

If Philip Roth chronicled the price of American success in Jewish American idioms, Carver was the chronicler of American failure. He described the characters in his stories as “people who don’t succeed at what they try to do, at the things they want most to do, the large or small things that support the life.” Carver was born into that tough life. His family was of Scots-Irish origin and had moved from Arkansas to rural Oregon. In 1987, Carver told an interviewer that nobody in his family had gone beyond the sixth grade. “My parents could barely read and write. My dad was a laborer. My mother was a housewife. So, what can I say? My upbringing was culturally impoverished, that’s the long and short of it.”

When Carver was 3 years old, his family moved to Yakima, Washington. His father, Raymond Sr., worked in a sawmill. Within a few years, the elder Carver, who drank heavily, fell ill and lost his job. Ella, Raymond’s mother, became the principal breadwinner and the major influence on her son Raymond. She insisted that he stay in school and encouraged him to read widely. The family was constantly on the move, never living in one house for more than a year at a time. But despite this constant moving, Ray managed to finish high school. College was not an option he considered.

Ray Carver and Maryann Buck met in that high school and married soon after his graduation. He was 19 years old; she was 16. They had two children within two years. From age 20 to 30, Carver supported his family by working in a range of blue-collar jobs. He wrote poems and stories constantly. He also drank constantly, “Liquor had a grip on Ray,” said his friend Tobias Wolff. “You could almost feel the strength of that grip from the look of him. He seemed restless, queasy.”

Carver wrote many poems before he set himself to writing short stories. And though today we remember him as a master of the short story, Carver wanted to be remembered primarily as a poet. “I began as a poet. My first publication was a poem. So I suppose on my tombstone I’d be very pleased if they put ‘Poet and short-story writer—and occasional essayist.’” Asked what poets influenced him the most, Carver answered: William Blake and William Carlos Williams. “William Carlos Williams certainly. I didn’t come to Blake until a good long while after I had started writing my own poetry. But Williams––very definitely. I read everything of Williams that I could get my hands on when I was nineteen or twenty years old.”

Carver’s poems and stories were first published in small literary journals. In 1967, after years of publishing in these “little magazines,” Carver’s “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please” was selected to appear in Best American Short Stories. More publications followed in quick succession, and with a growing readership came critical acclaim. The literary critic Frank Kermode wrote that “Carver’s fiction is so spare in a manner that it takes time before one realizes how completely a whole culture and a whole moral condition is represented by even the most seemingly slight sketch.”

A year before his death from lung cancer in 1988, Carver told interviewer Michael Schumacher that “the influence on my fiction would be the early stories by Hemingway. I can still go back, every two or three years, and reread those early stories and become excited just by the cadences of his sentences––not just by what he’s writing about, but the way he’s writing. I haven’t done that in two or three years, and I’m beginning to feel like it’s time to go back and reread Hemingway.”

I first became aware of Raymond Carver’s unlikely connection to Israel when I glanced at the title page of Maryann Burk Carver’s What It Used to Be Like: Portrait of My Marriage to Raymond Carver. The book is dedicated to the couple’s two children, Christine and Vance, “and in loving, vivid memory of Raymond Carver—The Abba—the Daddy of our house.” Why, I wondered, did Carver’s widow call him Abba, Hebrew for father? I found the answer in Maryann’s richly evocative memoir. The reason was that at the end of the 1960s, the Carvers spent an unsettling and formative semester in Israel.

In June of 1968, Carver and his wife, Maryann, flew to Tel Aviv. Maryann, then a student at San Jose State, had been awarded a grant from the California State College Study Abroad Program. Her first choice for overseas study was a program in Florence, Italy. The other option was Tel Aviv University, where the grant money would go further. So the cash-strapped couple chose Israel.

According to the rules of the California scholarship, Ray was also entitled to study in Israel, but the details of this promise were never made clear. And Carver, in a manner that friends described as typical of him, misunderstood this to mean that he would be a “writer in residence” at Tel Aviv University, an arrangement which never came to be. In Ray’s vivid imagination, he and his wife and kids had been promised “a villa on the Mediterranean” for living quarters during their year in Israel. Instead, they were housed in a small apartment in Ramat Aviv.

In her memoir, Maryann wrote, “We boarded an El Al flight bound for the Promised Land. It was a year after the Six-Day War. In less than a week Israel had shown the civilized world—and the uncivilized—what Zionists were made of. Now here came the Carvers, Gentiles from California.” Maryann took to Israel enthusiastically and applied herself to learning Hebrew at the university ulpan; Ray was frustrated in his attempts to navigate the Israeli bureaucracy and disappointed that the promises he thought had been made to him remained unfulfilled.

Their Ramat Aviv apartment was only a block away from the main gate of the university. Maryann noted in her diary that “Ray and Christi were not warming up to Tel Aviv.” Carver’s letters to friends in the States indicated that Maryann’s observation was an understatement. His sense of being “a Gentile” in Israel never left him. In sharp contrast, his wife and son Vance were enthusiastic about Tel Aviv, and about the whole country.

As Carver biographer Carol Sklenicka noted, “Although Ray had resided at 21 different addresses in his life, he could not learn to feel at home in Tel Aviv.” Living in Israel, Raymond Carver wrote, “was an incredible adjustment.” Israel, it seems was his anti-California. Sklenicka noted that “In Israel, American liquor was expensive and Ray disliked the sweet Israeli wines he ended up drinking …Worse, every Friday brought the Sabbath, which irritated him—“fucking bloody Shabbat begins this afternoon”—by making it difficult to shop for cigarettes or liquor, travel by bus, or go to the post office.” Years after his Israel sojourn, Carver told a friend that his alcohol addiction was exacerbated by that semester of drinking sweet wine. When he got back to California, he wanted only hard liquor; no more Manischewitz wine.

For Carver, Tel Aviv was a downer; Maryann remembers him looking out the window of their apartment and saying over and over again, “What am I doing in Asia?” Israel, Carver wrote a friend, put him in “a manic-depressive state of mind.” Particularly irritating to Carver was his dependence on public transportation. He had come to Israel from California, where he and Maryann drove everywhere. In Tel Aviv he had no car and no way of getting around other than by bus. Many visitors to 21st-century Tel Aviv experience the city as dynamic, hospitable, and edgy; the Tel Aviv of the late 1960s was not yet the international city it was to become in the 1990s. Tel Aviv struck Carver as a dreary, dusty city in which few people spoke English.

Though Maryann’s scholarship was for the full 1967-68 academic year, and the Carvers had signed a rental agreement for that period on their Tel Aviv apartment, Ray wanted to cancel all of these arrangements and return to the States after only four months in Tel Aviv.

When in September 1968 Tel Aviv’s main bus station was the target of terrorist bombing, an attack in which three were killed and scores were injured, Ray told Maryann that he was through with Israel. It was unsafe and unsettling. And he had written no short stories while there. They were going home to California, and would be leaving as soon as they could make travel plans. Maryann agreed, though reluctantly. Her sense of connection to Israel never left her and she felt enriched by the experience. Carver, by contrast, felt depleted by his time there.

Though he wrote no short stories while in Israel, Carver did write poems. Three of those poems, “Morning, Thinking of Empire,” “Tel Aviv and Life on the Mississippi,” and “The Mosque in Jaffa” are among his most widely read and anthologized. So it seems appropriate that among Israeli readers today, Carver is as well known for his poetry as for his prose.

Back in the States after his Israeli sojourn, Carver began drinking heavily. Drinking, he said, had once helped him write; now it was interfering with his writing. “I was going downhill fast,” he wrote. “My life as a writer was receding into the yeasty distance.” In response, he returned to the short story form with new energy. In 1971, two years after Carver and Maryann returned to California from Israel, he had yet another professional breakthrough when he published “Neighbors” in Esquire magazine. Carver told his wife that the idea for the story came from their time in Tel Aviv, when they had agreed to care for the apartment across the hall while their neighbors were on vacation. In a 1982 interview Carver recalled that “the neighbors were going to be away for a week. They asked us if we could look after their apartment and feed their cat. And I remember I said sure. I remember walking into the apartment and shutting the doors behind me. There were a lot of plants and things like that, and it was really kind of spooky because, when I shut the door, I knew that it was possible to do anything in there I wanted to.”

The Carver marriage fell apart in the mid-1970s. In 1977 Carver, with the help of his companion, poet Tess Gallagher, joined AA and gave up drinking. Carver’s breakthrough short story collection, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, was published in 1981 to great critical acclaim. From 1977 until his death from lung cancer in 1988, Carver was sober and productive. He joined the English department at Syracuse University, where he was a very popular teacher and colleague.

And while Carver may have thought he was done with Israel, Israel wasn’t done with him. In 1982 Moshe Ron’s rigorously faithful Hebrew translation appeared under the Am Oved imprint. In the 1980s and ’90s, three more Hebrew collections of Carver stories (again translated by Moshe Ron) were published by Hakibbutz Hameuchad. And in the 1990s, the translator and short story writer Uzi Weil published a selection of Carver’s poems. These volumes were very popular in Israel, and the influence of Carver’s style and content was evident in the work of Uzi Weil, Etgar Keret, and other Israeli writers of the ’90s.

I asked a number of well-read friends in Israel why they thought Carver’s poems and stories were popular there. The common denominator in their answers was that the unadorned directness of “Carver Country” speech appealed to Israelis’ sense of themselves—as "dugri": direct, brusque, and unembarrassed. These Israeli readers wanted to hear “authentic” American voices from the heartland, not neurotic Jewish voices from New York.

Israeli poet Michal Gindin wrote that:

“Uzi Weil’s beautiful Hebrew rendition of Carver’s poems convey the poet’s unique use of language and his bitter-sweet humor. There is something about Carver’s ability to express feelings without recourse to sentimentality that appeals to Israeli roughness. Personally, I love Carver’s ability to tell a story through an image. As if we are looking at a picture and can understand the unfolding story from its composition. And with that he conveys the pain, or the emotion––without sentimentality.”

Gindin’s observations about Carver’s popularity among Israeli readers reminded me of Carver’s comments about Hemingway’s early stories—for Hemingway too is very popular in Israel. In the 1970s and ’80s, his novel The Old Man and The Sea was part of the general high school curriculum in Israel, and familiarity with that novel was necessary if one wanted to pass the bagrut, or matriculation exam.

Today, translations of Carver’s poems and stories remain popular among Israeli readers and his work also lives on the Israeli stage. Many of his stories have been dramatized, including “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” and “Neighbors.” The work of the “chronicler of blue-collar despair,” who, as his biographer put it, “could not learn to feel at home in Tel Aviv” returned to Israel in triumph, but only after his death. And that is a story worthy of Raymond Carver.

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.