Some Reflections on Chaim Potok’s ‘The Chosen’

The novel, published 50 years ago today, shaped the American Jewish encounter with Hasidism and Orthodoxy, while giving a pretty good play-by-play account of a baseball game

Fifty years ago today, on April 28, 1967, Chaim Potok’s first novel, The Chosen, was published. It would stay on The New York Times best-seller list for 39 weeks and become a finalist for a National Book Award in 1968. Despite the passage of time, the novel has continued to stay in the public eye, from its sequel, The Promise, published in 1969, a film adaption in 1981 that starred Robby Benson (the former teen heartthrob familiar to my generation as the voice of the Beast in Disney’s animated Beauty and the Beast), a short-lived off-Broadway musical produced in 1988, and the drama co-written by Potok that premiered in 1999. Like many Jewish day-school graduates, I first encountered the novel as a reading assignment in the eighth grade some 20 years ago. I could not put it down.

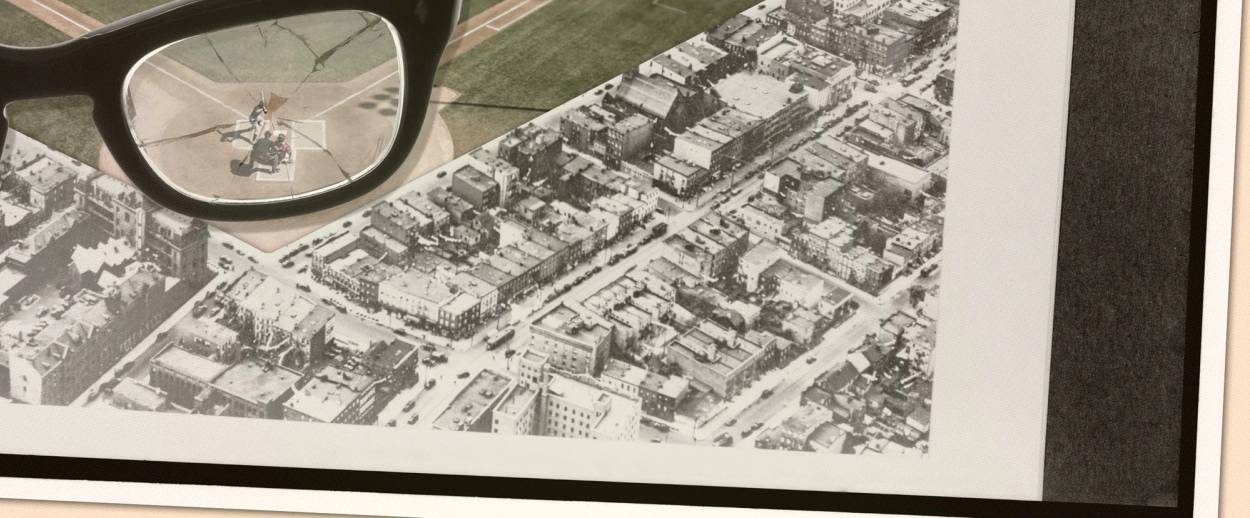

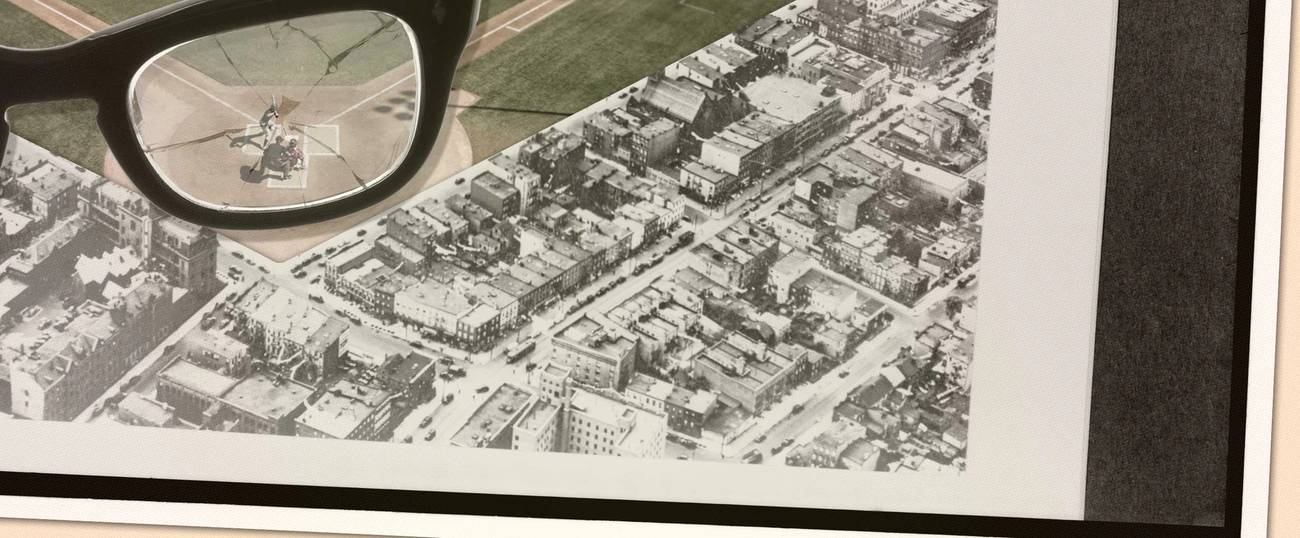

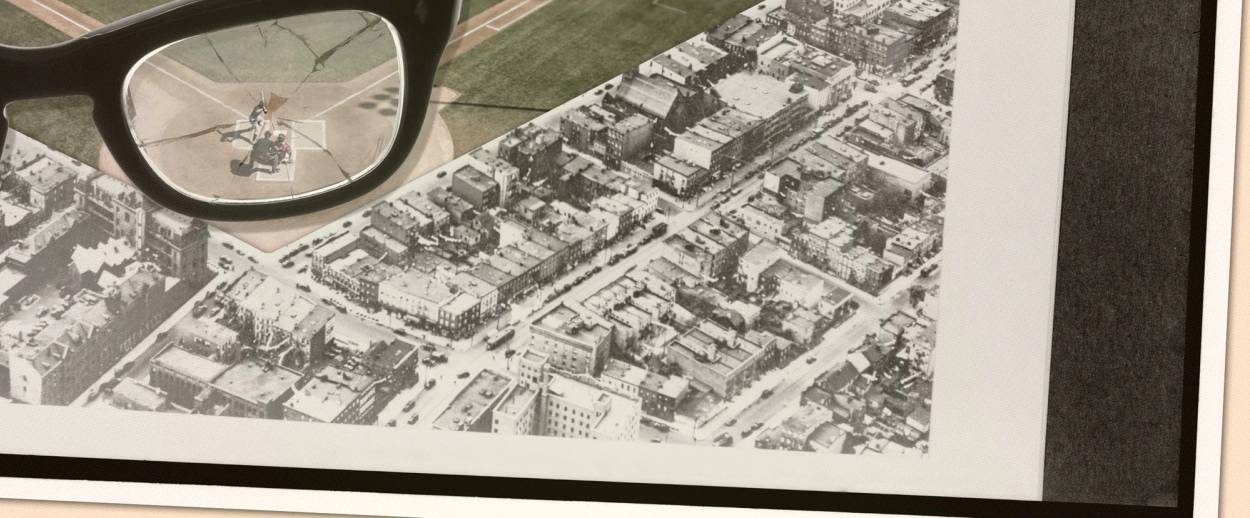

Potok crafted a marvelous story in which the worlds of two Williamsburg boys from two distinct communities, one Hasidic and one Modern Orthodox, collide due to a chance meeting on a baseball diamond. Throw in the historical backdrop of the Holocaust and the founding of the State of Israel, as well as the relative ease of the prose and the cleanliness of the subject matter, and it is no wonder the book remains a staple of the middle-school curriculum to this day. Among the countless issues that The Chosen deals with: the birth and history of Hasidism, the power of the Rebbe in Hasidic practice, religious responses to Zionism and the State of Israel, academic study of the Talmud, and father-son relationships and Freudian psychoanalytic theory. Quite an intense list for an eighth-grader to confront in one novel!

It is only fitting that a book that is so “Jewish” opens with a description of arguably the most Jewish of all sports in the most Jewish of all American communities: baseball in Brooklyn. Ever since Lipman Pike was a star Jewish baseball player in the 1870s, Jews have always had a connection to the game. Central to the novel is a highly detailed description of a softball game between Reuven Malter’s Modern Orthodox school and Danny Saunders’ Hasidic school. As Potok sets out for the reader, the game itself is a product of America’s entry into World War II, as a number of teachers in the Jewish school system wanted to show the gentile world that yeshiva students were just as physically fit as public school students. The description of the game is riveting, especially when we are introduced to Malter and Saunders who meet for the first time during the heated game. Ultimately, Saunders smacks the ball right toward Malter on the pitcher’s mound, knocking off his glasses and sending him to the hospital where the two begin to cultivate their friendship in earnest.

Potok, clearly versed in the sport of baseball, wears the hat of a professional sports commentator throughout this opening chapter, to the extent that one can literally prepare a detailed box score of the fictional game. (Personal disclosure: I’ve done it. Although, for the record, in the top of the fifth inning, the inning in which Malter gets knocked out, the No. 2 batter is skipped in the batting order, and instead the No. 3 batter leads off the inning.) His biases toward Hasidim are also apparent from the opening pages. Time and time again the aggressiveness and sense of superiority of the Hasidim are asserted. In perhaps one of the tensest scenes in the opening chapter, when Saunders and Malter meet, Saunders says, “I told my team we’re going to kill you apikorsim this afternoon.” In Rabbinic Hebrew and in Yiddish, apikores refers to a heretic. Potok has transformed the baseball game into a religious war, with a clear delineation from the perspective of Malter, from whose perspective the book is written in first person. Amazingly, Potok actually has a bit of a following in the Lubavitch world, as his wife lived in Crown Heights and Potok attended a Purim farbrengen with the late Lubavitcher Rebbe in 1973. The Rebbe, fully cognizant of Potok’s presence at the occasion, spoke about the importance of professional writers using their platform in the service of God. Potok also modeled the fictional Ladover Hasidic group after Lubavitch in his 1972 novel, My Name is Asher Lev, and its 1990 sequel, The Gift of Asher Lev.

In evaluating the novel’s impact on my own life, I’m most drawn to the personal religious struggle of the protagonist, Malter. Perhaps Malter’s struggle is meant to autobiographically reflect the real tensions Potok himself experienced. Indeed, the similarities between Potok and Reuven Malter are readily apparent throughout the book. Potok was born in 1929, the same year as the fictional Malter, and Malter studies at the Samson Raphael Hirsch Seminary, an institute that is modeled after Potok’s alma mater, Yeshiva University, and its affiliated Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (interestingly, there in fact exists a Yeshiva named after Samson Raphael Hirsch on the other side of Washington Heights from Yeshiva University). Malter’s last name is itself a reference to Henry Malter, a prominent Jewish studies scholar in the early 20th century who is famous for his critical edition of Tractate Ta’anit of the Babylonian Talmud.

Even the fictional rabbis affiliated with Hirsch, the Talmudist Rav Gershenson in The Chosen and The Promise and the impassioned traditionalist Rav Kalman, who serves as Malter’s antagonist in The Promise, are based on real rabbinic personalities. Professor Shlomo Havlin of Bar-Ilan University has written a number of scholarly articles that mention The Chosen, and he proposes that Gershenson is based on the famous Talmudist and leader of 2oth-century Modern Orthodoxy Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, while Kalman is based on Rabbi Yerucham Gorelick, a noted Talmudist and prime disciple of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s uncle, Rabbi Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik. These suggestions are not unlikely. Potok himself was a graduate of the Orthodox day-school system in the Bronx and of Yeshiva University’s high school and college, though he ultimately broke with his Orthodox upbringing when he received ordination from the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) affiliated with the Conservative movement. Nevertheless, while Potok’s book features a fictional JTS institution, called the Zechariah Frankel Seminary, Malter pursues his studies at Hirsch and, indeed, much of The Promise focuses on Malter’s pursuit of rabbinic ordination and ultimately his struggle to receive a teaching position there.

Potok was certainly reflecting on his experience in Yeshiva University during the late 1940s (Potok received his bachelor’s degree in 1950), and at a certain level, the struggles that Malter encountered then could have taken place today. Potok’s connection with JTS and academic Talmud becomes even more pronounced in The Promise, where Malter continues to develop the academic Talmud skills that he had already demonstrated to Rav Gershenson in The Chosen and utilizes a number of academic Talmudic examples during his oral exams with Rav Kalman and Rav Gershenson in order to receive rabbinical ordination.

Havlin has skillfully reviewed the various examples Malter cites during his exams and identifies various flaws, in his opinion, in these cases. One of the people whom Potok thanks on the opening page of The Promise is professor David (Weiss) Halivni, a Holocaust survivor and longtime Talmud professor at JTS and Columbia University who is universally acclaimed as one of the pioneers of the academic Talmudic approach. Havlin actually finds one of the cases that Malter cites in Halivni’s 1969 work, Mekorot u-Masorot on Seder Nashim.

Halivni lives in the Shaarei Chessed neighborhood in Jerusalem, and I recently saw him one Shabbos morning at the Kahal Chassidim synagogue. While it may seem strange to run into one of the foremost academic Talmudists davening at an Ultra-Orthodox shul in Jerusalem, where the congregants would not generally support his scholarly approach, in praying there, Halivni is true to the sentiments he expressed in his 1983 resignation letter to JTS: “It is my personal tragedy that the people I daven with, I cannot talk to, and the people I talk to, I cannot daven with. However, when the chips are down, I will always side with the people I daven with; for I can live without talking. I cannot live without davening.” After davening that Shabbos morning, I went up to Halivni to ask him about his relationship with Potok. After exchanging warm greetings and expressing his joy in being recognized, Halivni discussed the many ways the fictional Malter and the Talmudic methodology he uses in The Chosen were modeled after him and his own personal work. With a warm smile and a wink, Halivni told me: “I am Reuven Malter.”

In the initial reviews of the book, disseminated across the spectrum of the Jewish world, reviewers noted the many of the subtleties that Potok grappled with. In May 1968, writing in Agudath Israel of America’s (now-defunct) monthly, The Jewish Observer, H.D. Wolpin was quite critical of Potok’s novel. Although the book had scaled the heights of the best-seller list and brought the story of two yeshiva boys to readers across the county, Wolpin took issue with the book’s portrayal of Hasidim as strict and austere. According to Wolpin, “The fundamental error, however, is the assumption that Chassidism is a joyless concentration on suffering. It is widely known that Chassidism teaches that even one’s misfortunes should be accepted with rejoicing.” Wolpin also claimed that Malter’s father engages in biblical criticism, a path that Malter has similarly followed. While the topic of biblical criticism appears in Potok’s later works (for instance, in his 1975 novel, In the Beginning), in both The Chosen and The Promise, the academic/scientific method used by both Malter and his father is limited to the realm of the study of Talmud. Although this is seemingly a highly nuanced distinction, it has significant theological implications, and Orthodox institutions across the world to this very day might feel comfortable with academic Talmud but not with academic Bible. Wolpin made it clear that Potok’s JTS education permeates the storyline, and as Danny Saunders leaves his rabbinic studies to enter psychology graduate school, he wrote:

We see nothing wrongful in Danny’s decision per se. A livelihood must be sought, and the sciences provide honorable professions. But if the brilliant boys of Danny’s background were to turn en masse to the secular establishment, who would become the manhigim [leaders] we so desperately need in the future? Chaim Potok, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, provides his answer at the novel’s close that Reuven Malter, a boy of clean-cut, almost Superman-like mien, will become the rabbi, and his views on Bible malleability give clear indication that he will be a Conservative Rabbi.

On a certain level, the reviewer Wolpin was proved wrong: Malter remains in the Orthodox camp in The Chosen’s sequel, though it is clear that he still carries within himself the very same issues with the traditional Orthodox path that Potok had. It is for many of the same issues that Wolpin had with the book that The Chosen has found itself listed as “N” for not acceptable in a list offered by Torah Umesorah (although specifically not endorsed by it) that rates secular books as to their suitability for Jewish children. The reviewer notes that the “entire book revolves around denigrating of chassidim in particular, and very religious ‘unenlightened’ Jews in general, as being backward, closed-minded, superstitious, and unworldly.”

Most interestingly, a review of The Chosen by Zvi Scharfstein in the Hebrew-language Ha-Doar (published by the Histadruth Ivrith of America) on June 23, 1967, titled “Apikorsut in Williamsburg,” provides a glimpse of how the book is more often remembered today. Scharfstein, a noted Hebraist, pioneer in the teaching of Hebrew in America, and himself a professor at JTS, notes the instant success the novel enjoyed in non-Jewish circles and the impact the book had had on non-Jewish readers who would now be able to see Orthodox Jews in a new light. No longer would these traditionalists be viewed as strangers or foreigners, because their rich spirits and lives had been displayed so humanly in Potok’s work. None of Potok’s inner turbulence vis-à-vis Orthodoxy—the central focus of Wolpin’s writing—even appears in Scharfstein’s review. Instead, Scharfstein waxes poetically about a Jewish novel that achieved worldwide fame and cast a positive light on Orthodoxy and the study of Torah.

Looking back at the novel’s critical and sustained success, we can say today that Scharfstein appears to have been right. Although he focused his enthusiasm on the exposure of non-Jewish readers to the Jewish themes of the book, he could have just as well been describing the unaffiliated Jewish reader encountering Orthodoxy through The Chosen. While Potok himself was clearly critical of certain rigid attitudes in Orthodoxy, he fashioned a detailed, enduring, and intimate picture of Orthodoxy and of the Hasidic home, which countless Jews have credited with helping to inspire their own religious observance.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Aaron R. Katz is an associate in the corporate and securities practice at Greenberg Traurig. He lives with his wife and three children in Israel.