A Masterful Account of Humiliation and Despair

Robert F. Worth’s ‘A Rage for Order’ brings the broad disappointments of the Arab Spring to the human level

When the corrupt and autocratic regimes of the Arab world began to topple one after another, in the Arab Spring of 2011, it would have taken a cold heart not to share in the hope of so many millions of people. But five years later, it seems that the cold-hearted—those who were skeptical of the possibility of genuine progress, those who warned that revolution would give way to civil war—were right all along. Revolutions never seem to bring the happiness they promise: not in France in 1789 or Russia in 1917, and not in Egypt or Libya or Syria in 2011. Instead, the Middle East has gone from bad—repressive dictatorships built on secret police and theft—to worse—open civil war and genocide.

For Americans witnessing these events, the great question tends to be what role our government played in the disaster. The problem is that there are several plausible answers, all of which contradict each other. In Iraq, America took the most active possible role, invading the country in 2003 to remove Saddam Hussein; today Iraq barely exists, divided irretrievably between Kurds, Shiites, and Sunnis. With Iraq in mind, when it came to overthrowing Muammar Qaddafi in Libya in 2011, the UnitedStates and NATO refused to invade, restricting their role to supporting the rebels with air strikes. But today Libya too barely exists, its territory carved up among feuding tribal militias. Looking back on Libya, then, President Barack Obama steadfastly refused to intervene in Syria, even retreating from his own “red line” about the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons. And today Syria barely exists, as rebellion grew into a years-long civil war that has cost hundreds of thousands of lives and turned millions into refugees. Into the vacuum has stepped ISIS, the Islamic State, whose barbaric violence and cruelty have shocked the world, though not exactly into action.

Invasion, limited intervention, and nonintervention all turned out, in the Arab world, to have equally disastrous results. Today, the Middle East is so ruinous that most Americans have simply thrown up their hands, resorting to the old platitude that did such hardy service in Yugoslavia—that these are age-old hatreds, which have to be allowed to play themselves out. Pundits now talk of a new Thirty Years’ War, unfazed by the fact that the first Thirty Years’ War, in Europe in the 17th century, killed perhaps one-third of the population of Germany.

In his new book A Rage for Order: The Middle East in Turmoil From Tahrir Square to Isis, Robert Worth does not offer any advice for the State Department or any forecasts of what will come next in the Arab world. Rather, Worth, a longtime foreign correspondent for the New York Times, offers a series of snapshots and profiles from the Arab Spring and its aftermath, showing how events unfolded at the scale of individual lives. This is an important service, since when we talk about the Middle East, we tend to use large religious and ideological abstractions—Sunnis and Shiites, secularists and Islamists. Worth brings those words back to their roots in the lives of real people, showing how people who never dreamed of making war or revolution ended up being unmade by them.

Perhaps the most painful and illustrative story in A Rage for Order is that of Aliaa Ali and Noura Kanafani, two young Syrian women. In 2011, when the Arab Spring came to Syria and the rebellion against Bashar al-Assad began, Aliaa and Noura were best friends, constantly in and out of each other’s houses in the Mediterranean city of Jableh. They paid no attention to the fact that Noura was a Sunni, part of Syria’s Muslim majority, while Aliaa was an Alawite, a follower of the minority sect that governed the country through the Assad regime. Indeed, Worth writes that Noura once turned down a marriage proposal from a Sunni suitor because he was so hostile to Alawis: “I can’t live with a man who thinks Alawis are forbidden,” she told Aliaa.

That these friends would end up as enemies is not exactly a surprise. We have seen the same thing happen too many times, between Serbs and Croats or between Hutu and Tutsi, to be surprised when the claims of the group destroy the bonds of individuals. Still, it feels shocking to read about how Aliaa and Noura turned against each other, driven by the increasing violence between Sunnis and Alawis, the rebels and the regime. The sinister thing about identity is that it is simultaneously the emptiest descriptor—knowing a person’s race or religion tells you nothing about what they are like—and potentially the most important. Once people feel threatened as a group, they will start considering themselves solely as members of that group, simply out of self-defense. The threat of violence provokes preemptive violence; both Alawis and Sunnis are convinced that they are the victims of the others’ aggression. Today, Noura and Aliaa live in different countries and no longer speak, each full of hatred and suspicion of the other.

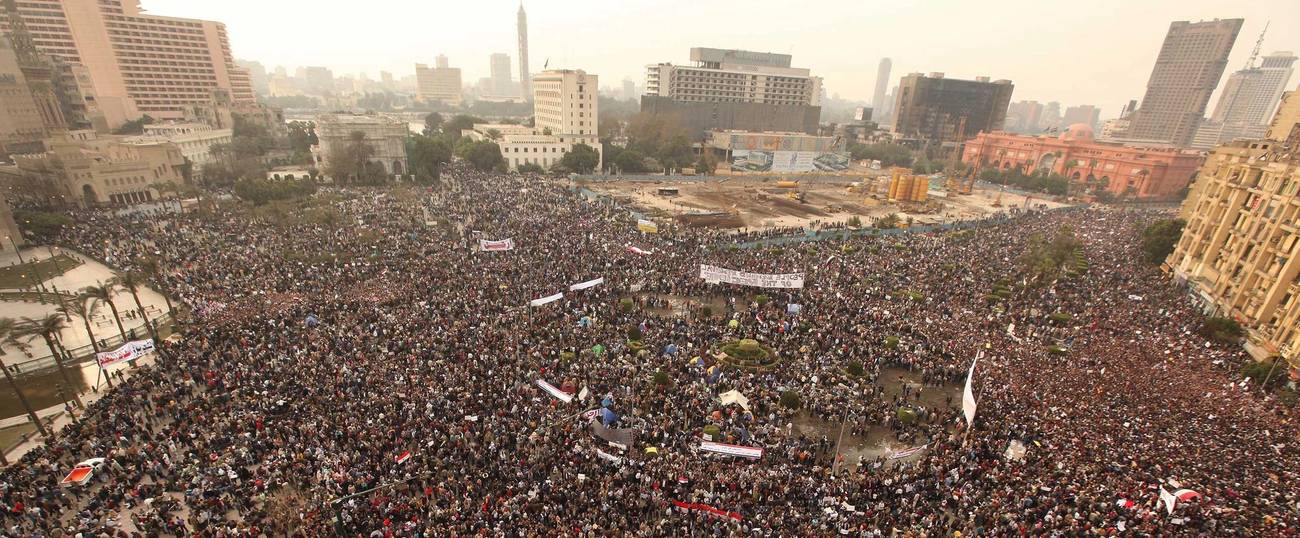

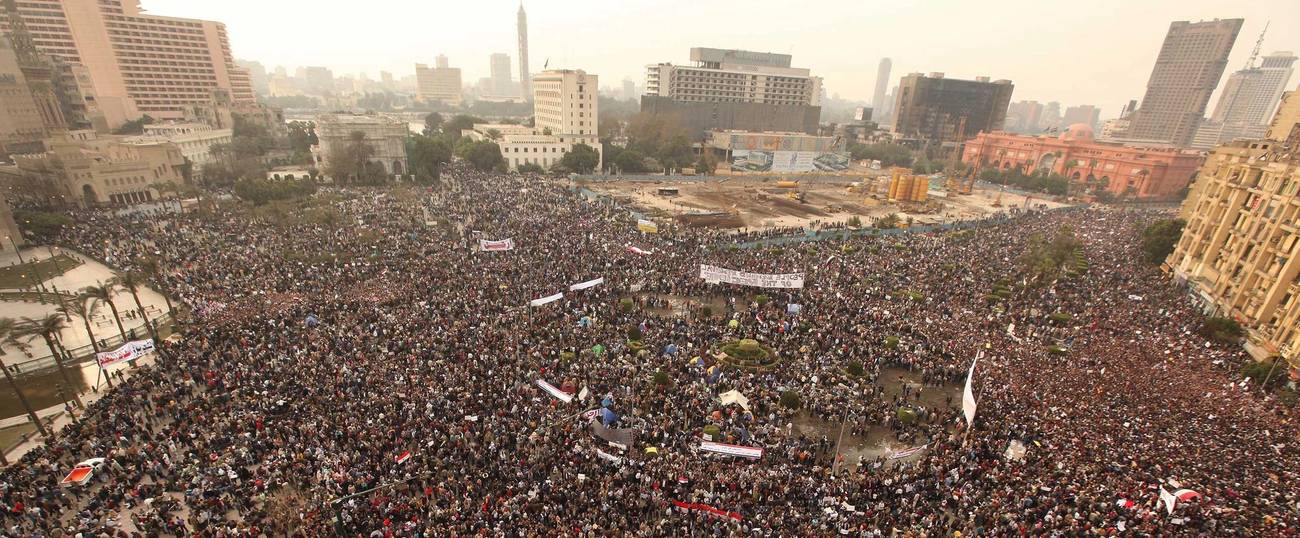

How can this be the end of a process that started with so much hope? Worth, who was present in Cairo’s Tahrir Square when protests began there in January 2011, felt about the Arab Spring just as Wordsworth did about the French Revolution: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive.” In Worth’s telling, Tahrir Square sounds like a bigger and more earnest version of Zuccotti Park during the Occupy days—a utopian space where society seemed to be recreating itself. Muslim Brothers and secular liberals put their differences aside for the common goal of overthrowing Hosni Mubarak. On Feb. 11, when news came of Mubarak’s resignation, Worth saw the crowd react: “People were hugging each other, running wildly back and forth to the balcony, their eyes glowing with tears and disbelief. … In the street, a man running past almost knocked me down, screaming at the top of his lungs, ‘Our freedom! Our freedom!’ ”

But in Egypt, as in Syria and the other places Worth covers, the initial enthusiasm obscured the fatal deficit of trust among citizens. Divisions between liberals and Islamists, civilians and the military, rebels and supporters of the old regime, proved to be too poisonous and deeply rooted to be overcome. When the Muslim Brotherhood managed to elect their candidate, Mohammed Morsi, to the presidency, many former rebels urged the military to step in and oust him. The new military ruler, Adbel Fattah al-Sisi, immediately became the subject of a cult of personality, his likeness appearing on “flags, pins, pictures, chocolate, cups, and other forms of Al-Sisi mania,” in the words of a newspaper article quoted by Worth. When al-Sisi’s forces massacred 800 Islamists in Cairo, liberals applauded.

In Egypt, however, at least the state survived. The same can’t be said of Yemen, where the decades-long dictatorship of Ali Abdullah Saleh had no sooner ended than Saleh was back at the head of a Shiite coalition, doing battle with Saudi-funded Sunni forces. One aspect of the Arab disaster that Worth could have done more to explain is the role of Saudi Arabia and Iran as outside sponsors of violence: The money and weapons provided by these regional superpowers is what has allowed the violence in Yemen and Syria to continue for so long.

In Libya, too, the disappearance of the dictator exposed a society whose institutions had been totally hollowed out. Libya, like Iraq and many other Arab nations, was a country with no historical identity—it was created by joining together three separate Ottoman provinces—and therefore little ability to inspire loyalty. Here Worth meets a man named Nasser whose brother had been murdered in prison by the Qaddafi regime. Now, after the revolution, Nasser’s militia has captured his brother’s killers, and he is unsure whether to punish them himself or hand them over to the nominal government. Idealistically, he does the latter—only to find that the evidence he has compiled gets lost, and the prisoners are allowed to escape. In such circumstances, it’s no wonder that the tribe and the clan provide the only reliable source of authority and loyalty.

It is the disintegration of countries like Yemen, Syria, and Libya that, in Worth’s view, explains the rise and the surprising allure of the Islamic State. As his title A Rage for Order suggests, Worth sees the Arab peoples as motivated not by a longing for freedom or justice, but for something more basic: the rule of law, the basic predictability of life, that only a functioning state (in Arabic, dawla) can provide. “They wanted something they had heard about and imagined all their lives but never really known: a dawla that would not melt into air beneath their feet, a place they could call their own, a state that shielded its subjects from humiliation and despair,” he writes at the end of his book.

This is a Hobbesian view of government: Rather than a state of nature where all war against all, better to have a single ruler with a monopoly on violence, no matter how arbitrary. The caliphate declared by ISIS promises just this—a strong government based on religious principles, able to bring order to regions plagued by anarchy and civil war. The reality, of course, is something else entirely. Worth writes about a Jordanian man, Abu Ali, who sneaks into Iraq to fight for ISIS but is so terrified and appalled by its cruelty that within three months he sneaks back out again. Like so many of the men and women in A Rage for Order, he has been condemned by history to live in a time and place that offers no good choices.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.