Romance with a Mortician

Thinking about one’s funeral honors during a visit to New York

I have observed two varieties of morticians: the jovial and the tenebrific. The first type is the amateur humorist who has the talent to live with ease and to lay others to rest with such panache that it feels like they are being sent on a holiday celebration. The second type is the professional mourner who walks through life with the stamp of martyrdom, burying people with such scorn that the survivors feel guilty for not having chosen a more expensive funeral.

This particular story, in which I altered a few names out of respect for both the living and the departed, has a double preamble—double because strands of my Moscow Soviet past wove themselves into a braid of the immigrant American present.

Between 1987 and 1989, which were my first two years in the United States, I had the habit of visiting the periodicals room at the Rockefeller Library at Brown University. Once a week I would go there, sit in a deep swivel chair by the window, and peruse Russian-language newspapers and magazines, both émigré and Soviet. At the time, the largest émigré daily was the New York-based Novoye russkoye slovo (New Russian Word), to which I began to contribute essays and stories. For some reason the editors liked to place the ads for celebratory events and funeral parlors on the newspaper’s “literary page.” I remember seeing awkwardly rhymed ads for the services of an actor formerly of Moscow, whom I had met in Italy while our families waited for our U.S. refugee visas. In New York, the actor specialized in hosting parties:

Bar Mitzvah? Jubilee? A wedding?

Call now and book, no need for waiting.

I guarantee you joy and love.

Your party host,

Pyotr Perchikov.

I also recall the stylish ads placed by two undertakers competing for the bodies—if not the souls—of Russian Jews in the United States. The first, Jack Yablokoff Funeral Home, had been founded in the 1960s by the son of the Yiddish actor Herman Yablokoff, writer of the famed song “Pipirosn.” The second funeral business, Wolk Memorial Chapels, had been established in the 1980s by a recent Soviet émigré. The ads by the latter funeral service made mention of a (to my ear, Dostoevskian) “catalog of coffins.” By the early 1990s, I had stopped reading New Russian Word or contributing to it, and after moving to Boston in 1996, I interacted less frequently with émigré literary circles.

The second important note has to do with my old Moscow friend Sasha Beyn. Sasha was five years my senior, and in 1979, when our distantly related families became refuseniks and befriended each other, Sasha was a college freshman. In my Soviet sixth-grader eyes, he embodied Jewish strength and zealotry. Sasha grew up in a rough area of Moscow, worked out with a group of bodybuilders, and wasn’t afraid of walking around with a Star of David on the neck. The Beyns left in 1981, and my parents and I tumbled into refusenik purgatory and stayed therein for six more long years. Sasha didn’t have the softest of landings in the United States. He first worked at a greenhouse, then a gym, then delivered pizza, and only eventually was he able to transfer his Soviet credits and return to college. Several years later he got into law school and eventually built a thriving real estate practice. Sasha married late, in his fifties, and by a small coincidence, I’d met his wife, Deena—now the owner of a swanky boutique on Lexington Avenue—in the days of our Moscow youth, at the apartment of my close friend Maxim Krolik. Even though we live in different cities and don’t see each other often—and despite the Trump-era politics that put a wedge between many Russian immigrant friends—Sasha and I have retained each other’s affection and trust. And this finally brings me to the actual events at the tender heart of this story.

In the spring of 2018, I was invited to speak at the launch of an anthology of Russian-language prose and poetry in honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary. It was published in New York under the curatorship of Gene Gutsov, now a TV personality, but always a poet and essayist, and one of the vibrant centers of the Russian-American cultural landscape. The book was an ambitious volume featuring three generations of writers. I have known some of the contributors for decades: an attorney from Chicago who has become an ardent Ukrainian nationalist; a poetry translator who has given the English language almost the entire oeuvre of Osip Mandelstam; a feminist thinker best known for her long ode to the brassiere; a pathologist who cultivated the literary persona of a retired Navy SEAL; and other gifted writers who preserved and perfected their Russian sensibilities through years of exile.

The anthology’s website and Facebook page listed all of the sponsors, among them a distributor of alcoholic beverages, a chain of Russian food stores, a family of funeral parlors, as well as a list of predominantly Jewish Russian names, some of them Anglicized. The names of the principal benefactors, set in a large merciless font, topped the list: Mikhail and Marianna Wolk. (In Russian, Wolk, or Volk, pronounced with the first voiced consonant, means “wolf.”)

I invited several friends and acquaintances from New York and New Jersey to the launch of the anthology. At first, Sasha Beyn texted that he and Deena would be “thrilled to attend,” but then changed his mind. I telephoned him.

“What happened? I thought you guys wanted to come?”

“You see, it’s not that we don’t want to. I just can’t.”

“Sasha, did I offend you or something?”

“Of course not. I looked up the program. It’s just that I sued the main sponsor a couple of years ago. I can’t bear to see him. I’m really sorry.”

“Well, perhaps we could at least have dinner together …”

I’ve long ceased to be surprised by what my father calls the “politics of feelings.”

This time my younger daughter Tatiana joined me on the trip to New York. She writes poetry and helps me with translations into English. In our family, Tatiana is a fourth-generation writer, and I have always tried to take her to various literary events and gatherings. When I was a kid in Moscow—before our family became refuseniks—I used to hang out with my father and his fellow writers, and I know it was a stimulating experience for a budding dabbler in words.

We stayed in a hotel with a soothing name—The Lucerne. During the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak, in July 2020, the city would expropriate this old Upper West Side petite dame and turn it into a homeless shelter, much to the horror of some of the local residents. But the events I’m describing took place more than a year before the pandemic, when life seemed more immune to epidemiological catastrophes, and when Trump appeared to represent a greater threat to the liberal imagination than the ever-mutating strains of the deadly virus. At the time, at least to my internal Russian exile, the name of our hotel brought to mind Tolstoy’s story, in which the main characters stay in Lucerne’s “finest” hotel: “When I went up to my room and opened the window onto the lake, the beauty of this water, these mountains, and this sky literally blinded me at the first instant. I felt inner anxiety and the need to express somehow the surplus of that something suddenly having overflown my soul. At that moment I felt a need to embrace someone, tightly, to embrace, tickle, pinch, and in general do something extraordinary with that person and with myself.”

For our part, when Tatiana and I pulled apart the shades in our room at The Lucerne, we saw the gaping purple well of the hotel’s inner courtyard, ribbed with construction scaffolding and studded with grimy plastic buckets. But there was a nice bistro, Nice Matin, down below at the corner of Amsterdam and 79th, and just a couple of blocks away sat the Museum of Natural History, where Tatiana and I headed after a late breakfast of crispy croissants.

Once at the museum, I followed Tatiana to the Hall of Human Origins, where skulls and skeletons of our ancestors and near-ancestors bear witness to the misery of creationism, and then returned the favor by dragging her to the Rotunda to see the William Andrew Mackay murals. There, on the Rotunda’s southern wall, is my personal favorite exhibit, a mural celebrating the Treaty of Portsmouth between Russia and Japan, facilitated by the United States through Teddy Roosevelt’s personal involvement. I showed Tatiana a small miracle of cultural history: written beneath the portraits of three members of the Russian delegation are the names “Witte, Korostovets, Nabokov.” In the museum’s brochure, Konstantin Nabokov, distinguished Russian diplomat and the uncle of the future author of Lolita and Pnin, is mistakenly identified as Vladimir Nabokov, who was five and a half when the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed in Kittery, Maine.

At 6 p.m. we met my old friends Sasha and Deena at an Italian restaurant across the street from Lincoln Center. We rushed through dinner, without having enough time to catch up.

“Guys, just come with us,” I offered again. “I’ll get you in without tickets. Come now, Sasha. So you sued their sponsor, but it’s over now. Did you lose?”

“No, just about ended where we started,” Sasha replied with woe in his voice.

“Who is this type anyway?” I asked.

“He would describe himself as a businessman and patron of the arts. Forget about it … Why don’t we order more wine?” Sasha proposed.

“You want me to fall asleep at the reading?”

Deena asked for another glass of prosecco, Sasha helped us catch a cab, and ten minutes later Tatiana and I were walking past a small crowd of smoking old poets and their admirers as we entered the building of a historic synagogue on East 65th Street.

By the time we came inside the smaller sanctuary, where the anthology launch and reading were to take place, most of the pews were filled—save for the first two rows, reserved, as I surmised, for the readers and their families. I immediately fell into the hands of a reporter for a Russian TV station, a woman my age whom I’d met soon after coming to the United States. Tatiana waited patiently as I waxed poetic about the ”heritage of Russian Jews” in the United States, delivering a sermon she’d heard many times. We finally sat in the second row on the aisle. To our right, there was an empty seat with an untouched “Reserved” sign, and to the right of the empty seat, lying flat on the cushion, was a large oblong purse with a heavy chain for a strap.

It was then I saw my good old friend Yakov Shteynberg, a Russian translator of modern American poets. Yakov was slowly moving down the crowded aisle.

“Yakov, over here,” I called out, waving and pointing to the vacant seat to our right.

He sat down next to me and started sifting through the contents of his cognac-colored leather bag until he finally fished out a slim volume of poetry and proceeded to inscribe it.

Suddenly a gentleman of about sixty hovered over Yakov. His face was pallid; his hair, dyed ashen brown, was coiffed with such perfection that it almost didn’t move alongside the rest of his head. He wore a tight-fitting ventless sport coat with the color pattern known in Russian as “sparks.” The oversized round face of his wristwatch showed its diamonds from beneath the stiff cuff of his cream shirt. Next to the gentleman was a lady of about 50, her lips pursed and her bangs slanted à la secretary of a labor union at a piano factory someplace in provincial Russia, from which she may or may not have emigrated years ago. The lady nervously fingered her purse with a mother-of-pearl clasp.

“Why are you sitting in my seat?” the gentleman with the expensive watch sternly asked my friend Yakov.

“I’m a participant of the reading,” Yakov softly answered.

“What participant? No-no-no,” the gentleman said, and the “no-no-no” part came out in formidable English. “Can’t you see these are our seats?”

Yakov didn’t engage with the coiffed gentleman but instead simply got up and moved to a seat on the other side of the aisle. From the new seat he waved to me, as if to say, “It isn’t worth the fuss.” But I didn’t take heed.

“Why were you so rude to my friend?” I asked, turning to the gentleman and his lady companion. “He happens to be a wonderful writer. And he’s reading today. It was I who asked him to take the empty seat next to me.”

“And you, what exactly are you doing here?” the gentleman asked me.

“I’m an avenger of insulted poets,” I replied. “And you?”

“I’m the sponsor,” the gentleman demurred, lowering his gaze.

Throughout the evening, the “sponsor” and his lady companion kept staring at Tatiana, who listened with one ear while also watching YouTube on her phone. I could tell he really wanted to reprimand my daughter but held back.

At the conclusion of the reading, as Tatiana and I made our way to the long tables with viands and drinks arranged in the synagogue lobby, we came face-to-face with the publisher Olevin, formerly of Riga, later of New York by way of Tel Aviv. One of Olevin’s claims to fame was the publication of Kurt Vonnegut in Russian translation.

“She’ll make a great soldier for Israel,” Olevin greeted me and complimented my daughter. “Do you even know whom you clashed with at the reading?” he asked.

“No idea,” I answered sincerely.

“That’s Misha the Wolf, the biggest funeral director in all of the Russian New York.”

“No way? That Wolf? I remember his ads in New Russian Word. “A catalog of coffins … ”

“That’s right,” Olevin nodded. “A very big catalog. Back when you immigrated he only had one funeral parlor, and now he owns five. In Queens, in the Bronx, two in Brooklyn, and one on Long Island.”

“A whole wolf’s lair,” I tried to make a joke.

Tatiana and I eventually pushed our way to vodochka and red caviar (for me) and Coke and eclairs (for her), talked to several other participants of the launch, and left without saying goodbye to the organizers.

It was almost 10 p.m. Our taxi crossed Central Park and turned onto Columbus Avenue.

“Look, papa, Sasha and Deena are still there at the restaurant,” my observant daughter pointed out as she looked out the window.

They were indeed still sitting at our table, more than four hours later. Lucky hedonists, I thought as I snapped a photo of the nighttime sidewalk scene with Sasha and Deena hidden in plain view. And I immediately texted the photo to Sasha with the note “Password: Funeral of the Arts.”

Sasha immediately texted back. “Join us?”

“I wish I could, brat (which in Russian means ‘brother,’ not ‘spoiled kid’),” I replied. “It’s past Tatiana’s bedtime.”

Sasha texted again. “Sorry we didn’t catch up properly. Now you understand why I didn’t want to run into this funeral artist again. Glad we’re still on the same wavelength.”

And that’s how I was convinced, yet again, that art and death are inextricably connected, especially when morticians serve as art sponsors.

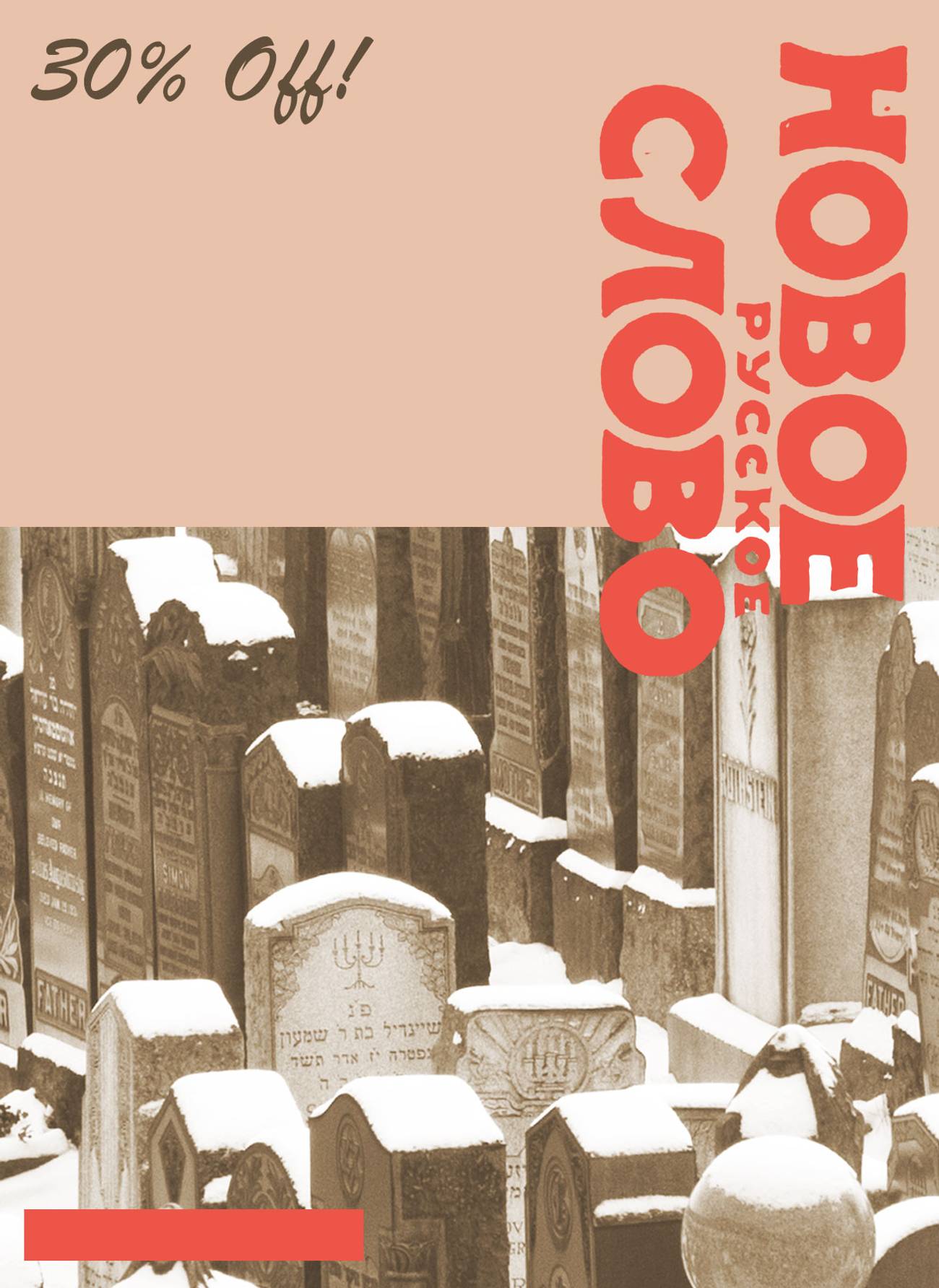

Ever since that visit to New York, I’ve been getting emails with promotional offers from Wolk Memorial Chapels. I would read some of them, out of curiosity, and delete others without clicking them open. But a few weeks ago, a handsome envelope arrived in my university mailbox. It contained an elegant brochure and a personal letter on the stationery of Wolk Memorial Chapels. Aside from complimenting my recent book of immigrant novellas, Mikhail Wolk was writing to “draw your attention to our new plan of purchasing burial plots at a cemetery where many of our former compatriots have been laid to rest—artists, writers, musicians.” Wolk Memorial Chapels offered “cultural figures like you a 30% discount for prepaying the funeral arrangements.”

My heart first soared, then grew heavy. I reread the offer, and I couldn’t stop thinking of life’s vagaries and of the vanity of philanthropists. “Finally,” I was thinking. “I’ve earned my place in the Russian American necropolis.” All I had to do now was retire from teaching, move to New York, and die a happy immigrant.

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.