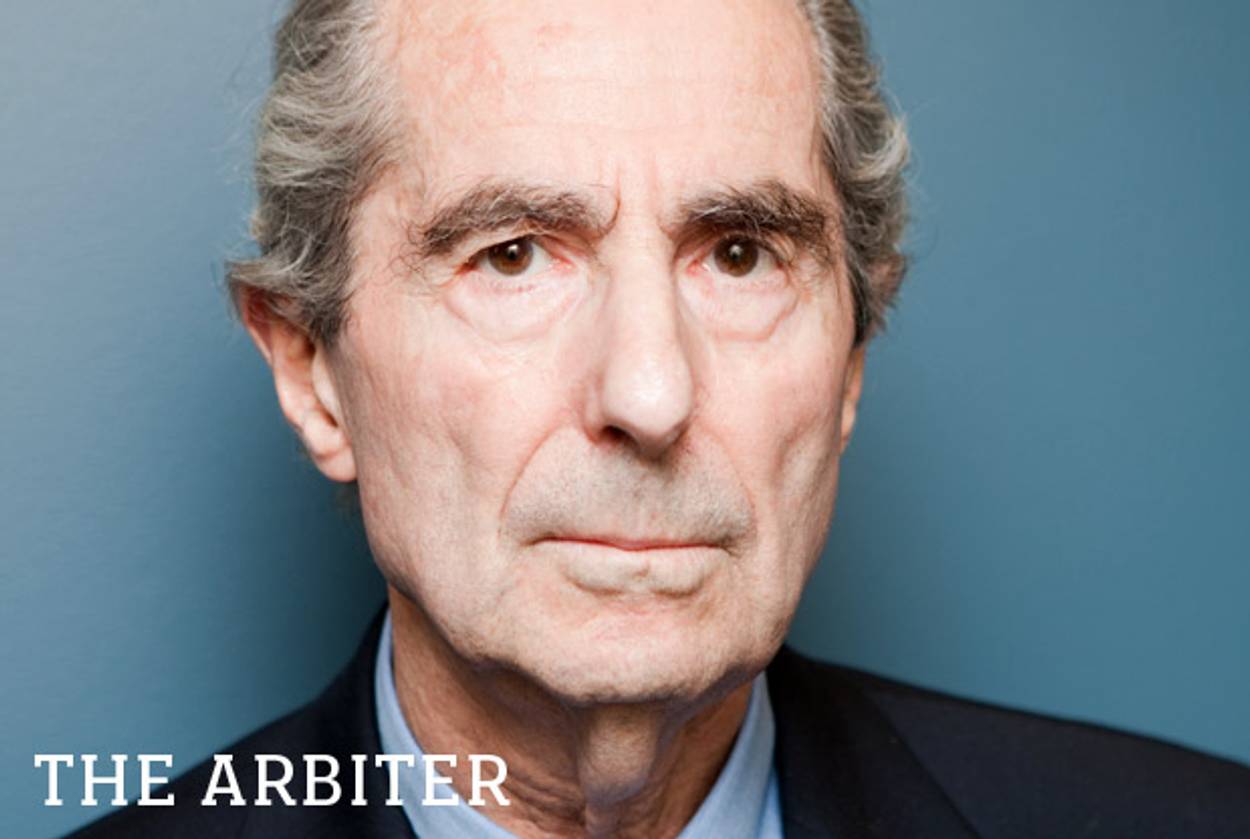

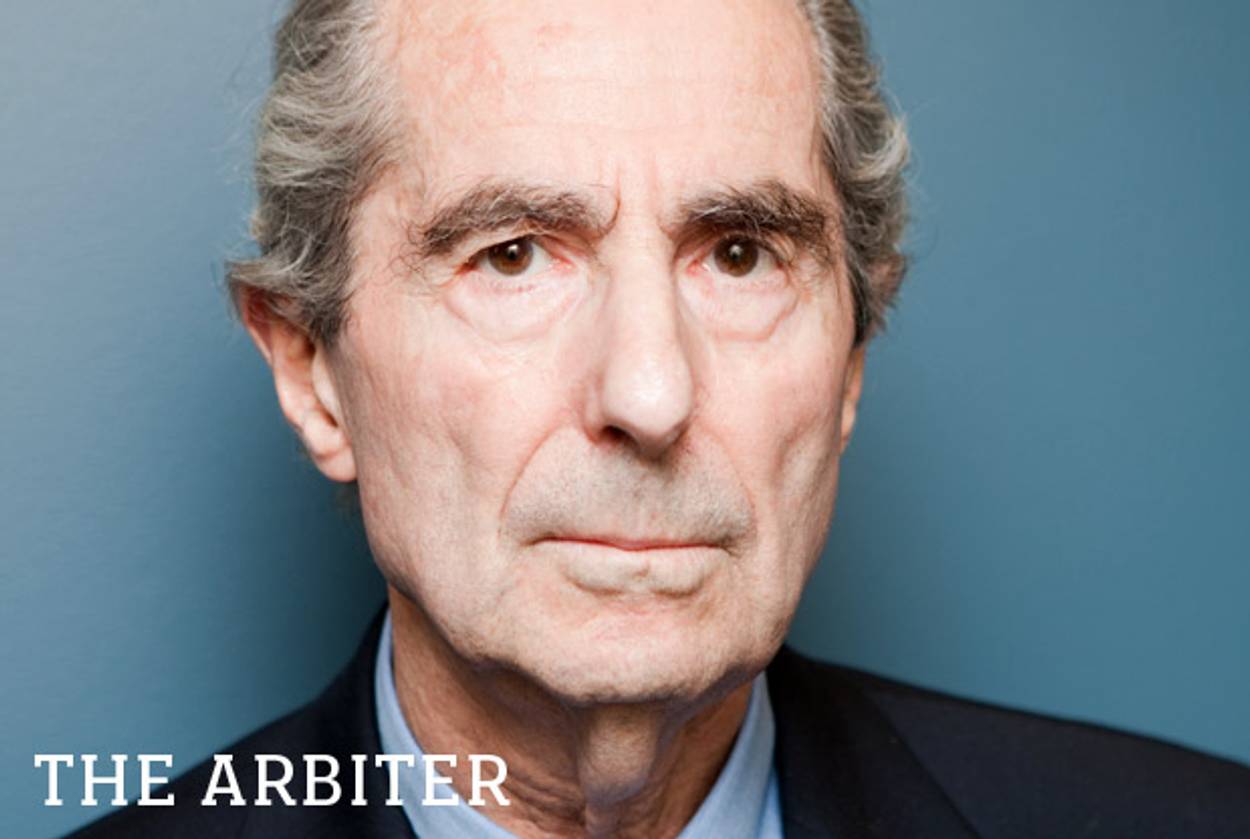

Roth Redux

Philip Roth’s defenders point to his later, more serious works to argue for his place in the canon. In truth, those books make clearer his weaknesses.

Last week, I wrote an unflattering column about Philip Roth. I focused most of my attention on Portnoy’s Complaint, and argued that its author was undeserving of his vaunted perch atop our collective esteem. Many of our readers were incensed, and most offered a common criticism—by ignoring Roth’s later work, went the cri de coeur, I was robbing him of his finest moments as a writer. In one variation or another, the question rang out: What about American Pastoral? Or The Plot Against America?

It’s a fair argument, and to address it we have to begin by taking stock of Roth’s evolution as a writer. Like Henry James, he has produced a body of work that is best experienced chronologically. Read your way through James from The Europeans to The Ambassadors, say, and you see a sketcher of tender, confined psychological scenes bloom into an artist capable of capturing transcendence, freedom, and others of the most elusive spirits that beat wild in human chests. What would you see if you read your way from Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus to Nemesis?

At first, youth, breathlessness, bravado, playfulness, glee. A child who grew up on the fault lines of modern America’s fiercest tremors—the Great Depression, World War II—Roth felt just enough of a quiver to sense the menace creeping underground but not enough of the heat to be forged, like steel, into a man whose words and deeds cut quick. Hence, the early novels. Hence, the giddy denunciations of community, of class, of expectations.

Roth himself summed it up best in an introduction he wrote for the 30th-anniversary edition of Goodbye, Columbus: “With clarity and with crudeness, and a great deal of exuberance, the embryonic writer who was me wrote these stories in his early 20’s. … In the beginning it simply amazed him that any truly literate audience could seriously be interested in his store of tribal secrets, in what he knew, as a child of his neighborhood, about the rites and taboos of his clan—about their aversions, their aspirations, their fears of deviance and defection, their underlying embarrassments and their ideas of success.”

His own idea of success soon led Roth away from these exuberances and toward loftier realms, the ones, possibly, he imagined more befitting of truly literate writers and their audiences. Sometime in the 1970s, Roth went meta.

There is, for example, Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s famous alter ego, being born as a creation of Peter Tarnopol, another of Roth’s alter egos, in the 1974 novel My Life as a Man. And there is Zuckerman again, five years later, in the lovely The Ghost Writer, sharing a stuffy country house with E.I. Lonoff, a thinly veiled version of Bernard Malamud, maybe, or Henry Roth, as well as a mystery woman who may or may not be Anne Frank. By 1993, with the uproarious Operation Shylock, we have Roth—or someone who bears his name and his facial features, or both—twirling cloaks and daggers in Jerusalem, chasing doppelgängers and observing history unfold, as only post-modern history can, like bits of mosaic falling off an ancient wall.

This stage in Roth’s career was a bacchanal, and like all festivities it, too, had to end. When it finally did, the historical stage began.

To this period—lasting roughly from American Pastoral in 1997 to The Plot Against America in 2004—belong the works that seem to inspire the greatest awe in Roth’s readers. As is evident anywhere from newspaper columns to Tablet’s inflamed comments section, the perceived wisdom holds that Roth finally matured in this period into the sort of writer he was always meant to be, America’s finest portraitist, on whom nothing of the nation’s past and whims and ills is lost.

A close reading, however, reveals his canvass to be much smaller. Roth the historical is Roth at his most myopic, unconvincing, and insecure. Confined to Lonoff’s cottage, Roth was radiant; freed in a fictitious America where Charles Lindbergh is president and Jews are reviled, Roth is lost.

To make sense of history, he applies patterns: American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Plot Against America are all told from a child’s point of view or revolve around memories constructed in childhood; all involve a once-Olympian hero falling to earth; and all are thrust into chaos by rampant, radical ideology shredding the fabric of what would have otherwise been an idyllic American society.

The most famous of these humbled men is Swede Levov. The protagonist of American Pastoral begins his life as a star athlete, an affluent son, and a beauty queen’s husband. He ends it in the squalor of a New Jersey ghetto with his daughter, a Weather Underground bomber living on the lam. She is skeletal, sickly, the victim of serial rape and stern beliefs. The meeting between father and daughter is the meeting between America’s sweet promise and its inexplicably sour present. This is how Roth ends the book: “They’ll never recover. Everything is against them, everyone and everything that does not like their life. All the voices from without, condemning and rejecting their life! And what is wrong with their life? What on earth is less reprehensible than the life of the Levovs?” It’s a question Roth never answers.

Others, however, have. In her fantastic 2006 novel Eat This Document, Dana Spiotta imagined a heroine who’s a lot like Merry Levov. After an act of violence gone awry and decades living under a false name and an assumed identity, the woman, now known as Louise Barrot, considers turning herself in and confessing her crimes. Like Roth’s novel, Spiotta’s, too, shifts frequently between past and present. But Spiotta is never content with terse, simplistic statements like “they’ll never recover.” She is capable of seeing much more than the curdling of expectations. Even amid the howls of politics and fate, she finds the time and the grace to allow her characters the subtleties and small fears of which we all are made. Her Louise, skipping from one persona to another, rarely raising her voice above a whisper, lives not just with the burden of having detonated explosions but with the far more unbearable weight of never really “being truly known by anyone.” Even though they’d lived a very similar life, she’d have little to say to Roth’s Merry, a creature of so much black and white that she converts to Jainism and plans her own self-starvation just to resolve the conflict of her existence.

In The Human Stain, Zuckerman feels the same burden. Even though he is released, in this novel, from the yoke of reflecting on his childhood and is permitted instead to observe the affairs of adults as they unfurl in real time, he is still bubbling with the sort of childlike indignation upon discovering that the world just isn’t fair. It’s a condition the critic Laura Miller nicely diagnosed: The screed with which Roth opens the book, she wrote, decrying the silliness of l’affair Monica Lewinsky, “has a certain Swiftian magnificence, but as a description of what happened in America in 1998 it is dead wrong. The nation was not caught up in a puritanical witch hunt; rather, Americans largely refused to be whipped into such a frenzy, in defiance of the best efforts of right-wingers and certain media figures.”

Roth is right there with the right-wingers and the hyperbolic media in his passion for the Manichean. To him, isms are always toothsome and vices always on the rise and America never more itself as when it teeters on the verge of self-destruction. But America isn’t so simple. The 1950s, McCarthyism and all, weren’t the Grand Guignol Roth made them out to be in I Married a Communist. And the 1960s, with all their rage, weren’t Merry Levov’s stark hideout. Even the dilapidated 1990s had more charm than Roth knew what to do with. Far more hysterical than his fellow Americans, then, he concluded his historical period by abandoning the real for the imaginary.

In The Plot Against America, Roth finally allowed himself to feel fear and loathing uncomplicated by these pesky nuances that well-formulated characters unfailingly force on a novelist. There were intricacies to his plot, sure, and a few haunting and beautiful moments, but there was no mistaking the book’s life force for anything more than a feverish exercise in what-if. The real anti-Semites that taunted the author as a child—taunts that transcended mere racial hatred and were colored by a myriad of other factors—were now full-blown murderous goons, trying on their jackboots in anticipation of pogroms to come. This is the same clarity, crudeness, and exuberance Roth had described as his chief motivator early on in his career, only now the glee gave way to gloom. And the gloom never dissipated: It is very much present in Roth’s recent books, marking the latest phase of his career. Uncharitably, I’ll call those novels of the last few years the novels of dying. Charitably, I’ll refrain from discussing them at all.

Looking back at Roth’s career one sees the same flightless narcissism growing stronger from one novel to the next. The bigger the challenge, the greater the disappointment. Stumbles that would have been forgiven in a book dedicated to smut and effervescence are much more noticeable in attempts to tell America’s history. Even when his prose his sharp—whether or not it is would be best left to personal taste—Roth lacks the ability to climb outside of his own head and give us the world writ large, the sole ability that has ever united the truly great practitioners of the craft, regardless of their styles and sensibilities.

What keeps him from transcendence isn’t necessarily solipsism. His friend and contemporary Saul Bellow shared the same preoccupations with the self; even his admirer Alfred Kazin noted that Bellow was “a kalte mensch, too full of his being a novelist to be a human being writing.” But when Bellow wrote, he soared. Augie March, Moses E. Herzog, Charlie Citrine—all are very much Saul Bellow, but also very much not him. They were born, like Athena, from their creator’s forehead, and then took to earth seeking justice, courage, and wisdom. They are us. They are humanity. They’re the stuff a Nobel Prize in literature is made of. They’re nothing like Nathan Zuckerman and David Kepesh and Mickey Sabbath, all of whom are only ever Philip Roth and never anything more.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.