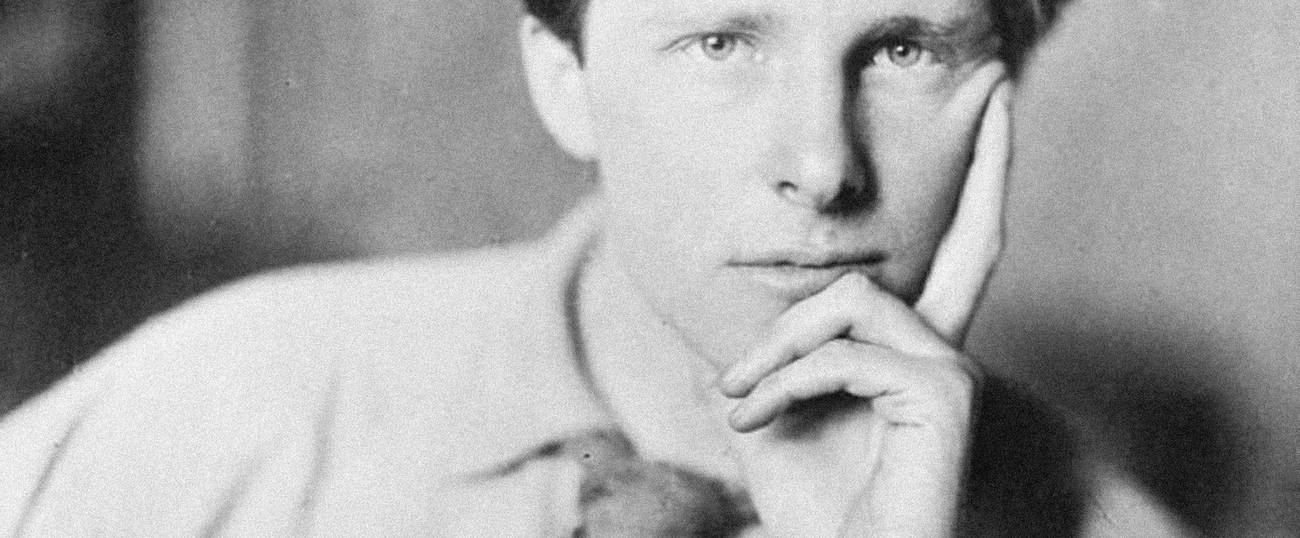

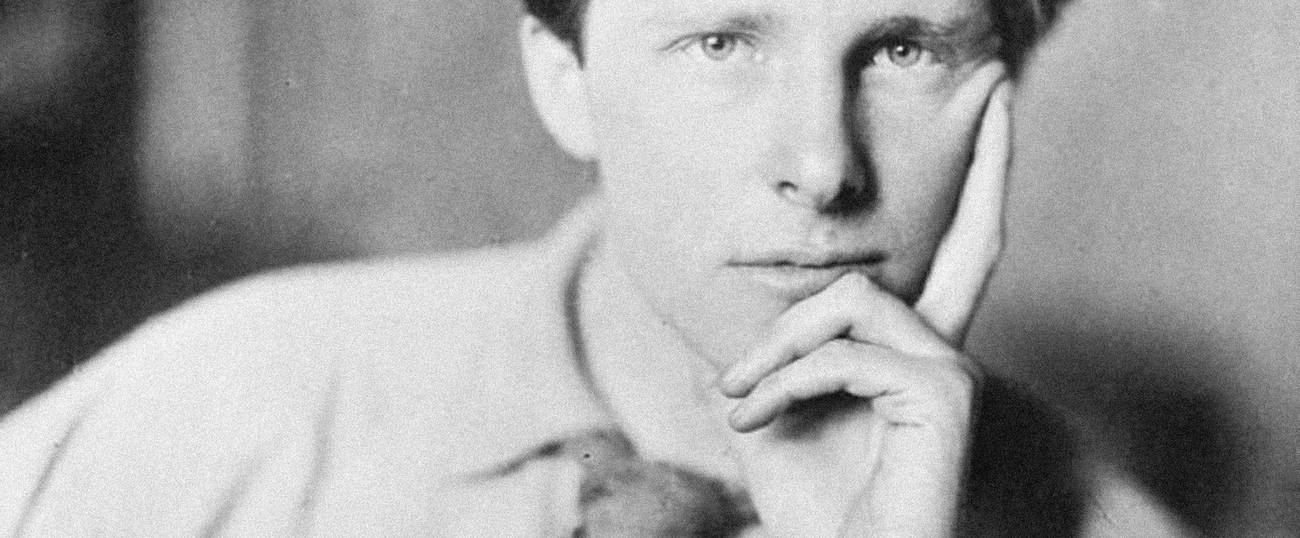

Rupert Brooke, My Favorite Anti-Semite

A Tablet continuing series of tributes to the people who hate us

Just a short bike ride from the center of Cambridge you will find a small hamlet called Grantchester. Down the dusty high-roads of the English countryside, a dim diffuse light shines through the droop-headed trees that float above the waters of the river Cam. And there, in this little ghost-forgotten nook of the world—so emblematic as to almost be reminiscent of the English countryside even to someone who had never visited it before—you can sense the presence of Rupert Brooke, the World War I sonneteer who lived in Grantchester while studying at King’s College and then died, 102 years ago this week, on his way to Gallipoli.

I have been reading the poems of Rupert Brooke for 10 years. On my bookshelf sit tattered first editions, reprints, collections of his experimental poetry, and a 1920s gravure portrait. In college, I helped a friend produce the only work Brooke ever wrote for the stage, a neogothic one-act called Lithuania. No poet has meant so much to me as Rupert Brooke. And so here in Grantchester I suffer the same fate of any who takes a great pilgrimage: Moments after arriving I have already started to dread the moment when I’ll have to leave—when the future will have become the past, when I’ll have to shake off my trance and leave the place Brooke loved so dearly to catch a 6 p.m. train back to dreary London. Hardly aware of my own cheesiness, I am declaiming muted verses to myself, hoping that like some incantation they might bring Rupert Brooke back to life as I walk down deeper into Grantchester to find the tea parlor where Brooke used to drink and study.

But the thing is, I wouldn’t want Rupert Brooke to come back to life because he was a raging anti-Semite.

This was a fact I learned with some discomfort two years ago when I was reading one of the most extensive biographies written about Rupert Brooke. I had been searching since high school for a biography of Brooke that didn’t get totally sidetracked by stories about some of his famous friends. (Brooke was known to have gone skinny-dipping with Virginia Woolf.) This biography was sidetracked by transcripts of Brooke’s correspondence about the pernicious Jewish presence in England. In the mind of my idol, I would not be a welcome guest in Grantchester, but a reviled trespasser.

If we like to read the lives of the artists we love, it is perhaps because we also like to imagine that, if not for time, there might have been some place in these biographies for us. We like to imagine that these artists would have sought out our company at dinner parties, and seen in us something of themselves, because, after all, we carry their sensibilities in us. This is perhaps why I have spent so much time memorizing Brooke’s poetry—as if by doing so, I consecrate some part of myself to the poems, and make them part of me.

Yet we are seldom, if ever, given any way to really know what an artist might have thought of us. We can’t know if Dostoyevsky would have found us insufferably boring, or if Camus would have laughed at the shallowness of our conceits. But any notion that Brooke and I might ever have been friends is clearly ridiculous. I can no longer imagine that he might have lingered long enough in the same room as me to form any opinion as to whether or not I was boring.

Regardless of whether or not we should forgive our favorite artists for these sorts of opinions, one thing is clear: We definitely want to. Holding it against them inevitably means excising both their work and their influence from our lives. It means life without them. For me, that would mean no memorizing sonnets, no reciting his verses under my breath, and certainly no trips to this English heaven called Grantchester. And can I live without Grantchester, after having spent so many years reading the same 140 verses about it? I know it well enough that I hardly need a map or to ask for directions.

The true cost of indulging and engaging my hang-ups about Brooke’s personal beliefs is really incalculable. And while some may call me unprincipled for throwing myself and my religion under the bus for a trip to a grassy suburb, I can’t imagine how petty and small-minded a person I’d actually have to be in order to abandon Brooke’s rhyme and meter and his Grantchester over something like a teensy-weensy little bit of anti-Semitism.

This reasoning, of course, is a contrivance to soften the realization that it does, in fact, bother me. Furthermore, having always thought myself bigger than squabbles like these, and having always thought that people who get caught up with these details are total philistines and dilettantes, I am bothered that I am bothered by it. Why can’t I get over it, entirely?

Any attempt at qualifying Brooke’s anti-Semitism with excuses about it being a different time or his never having really spent time with Jews is as silly as trying to converse with the dead. After all, telling ourselves something isn’t, in fact, that very thing as a way of dealing with it, is the easiest reaction to have. If human nature has one great talent it is its capacity for delusion.

Abandoning any hope that Rupert Brooke wasn’t an anti-Semite and loving his poetry all the same is perhaps the greatest show of dedication I can make to his craft and what he left behind, and the biggest honor I can pay to the 17-year-old whose sensibilities were as much the product of Brooke’s poetry as Brooke’s were of England. If poetry is meant to act as some lyrical parallax by which we learn something about ourselves and about beauty, it was never meant to be easy. It is difficult precisely because of what with such economy it is able to offer. We incorporate great works of art with our minds and our hearts; a pinprick is a small tribute for being forever changed by them. The pinprick of anti-Semitism is the price I pay for having this poet on my bookshelf.

Could such casuistry ever be dreamed up by anyone but a Jew?

Art exists in a place far beyond these plebeian trifles. Their money is no good here in Grantchester.

The prevalence today of movements aiming to scrub away any public homage to hateful white men would implore me to stop reading or talking about Brooke as some form of retroactive punishment. As one of the few American journalists who writes about him, I have the ability to hush the sound of his voice in this country by turning my back on him. That will teach him, surely. But I am too selfish. Future generations will have to quibble with his political and social leanings just the way I have. And perhaps, juggling their moral misgivings, they’ll come across some of the best lyrical poetry written in the 20th century, and, in brushing up against his genius, they will also perhaps, to quote the poet himself, see no longer blinded by their eyes. They might even take some minor comfort in the idea that Brooke didn’t live long enough to eventually become complicit with the Nazis.

In what is perhaps his most famous poem, Brooke once wrote: “If I should die, think only this of me; That there’s some corner of a foreign field that is for ever England.” That, after all, is why I came to Grantchester. Could I ever claim to have loved his poetry if I am not able to do him this favor—to abide his final will and testament and suspend my neurosis for one afternoon?

This small corner of the English countryside buried in moss and light ochre dirt and lined with uneven cobblestones as beady and bumpy and shrouded by stray blades of grass as those around the Vatican are all that remain of Rupert Brooke. In this place, time and all that belongs to it no longer matter. His heart, all evil shed away, lies here, in Grantchester. I have come to witness it, because in Grantchester he is more than an anti-Semite, and in Grantchester, I am more than a Jew.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.