May I Be as Jewish Then as I Am Today

In Ruth Wisse’s new translation, Jewish history is a tale of war that only makes us stronger

All great translations are the record of two wars. The first, fought over fidelity, must be won by the author, whose sound, style, and soul are to be preserved at all cost. The second, fought over familiarity, is the translator’s for the taking, because every great translation is as much a wild recreation as it is a faithful facsimile. More than a bit of Scott Moncrieff shines through his (not Proust’s) In Search of Lost Time, and Alexander Pope was so invested in his Iliad that his frenemy Richard Bentley quipped, “it is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer.”

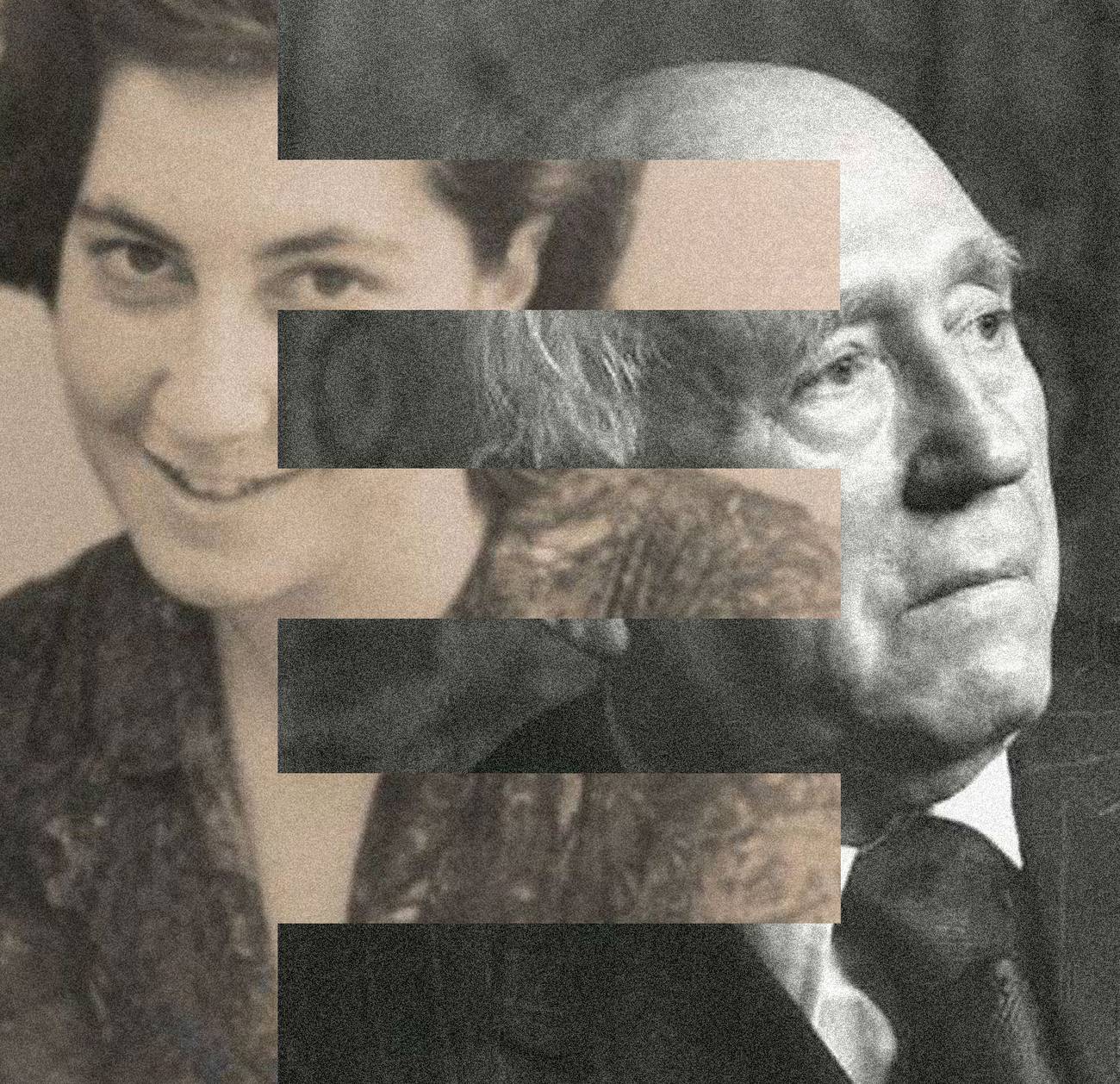

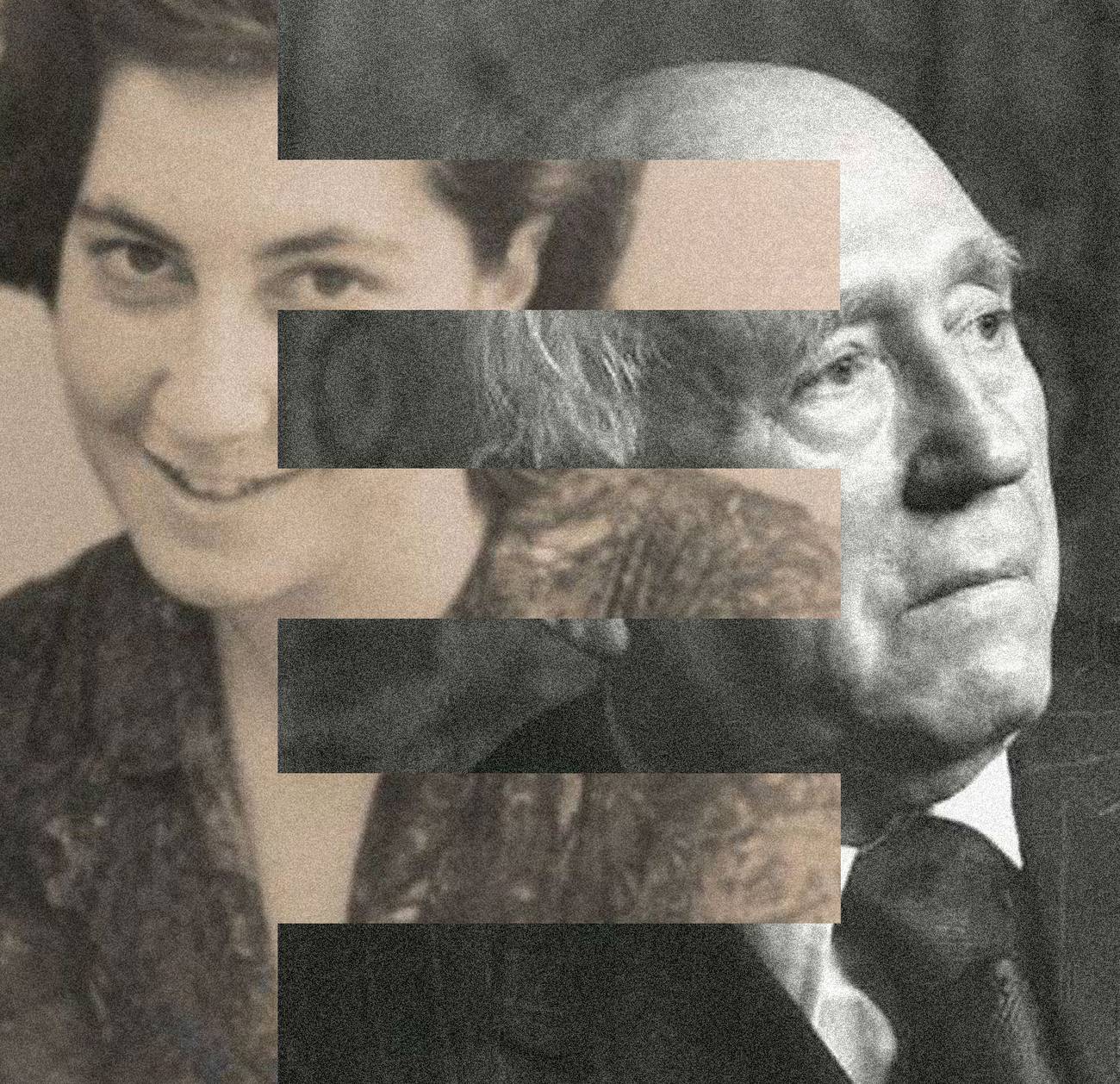

Add to that short and immortal list of combatants Chaim Grade and Ruth Wisse. The former was a writer doomed by circumstance to occupy a lesser rung on the ladder of Yiddish masters than his talent merits. The latter is our great scholar of Yiddish literature and a masterful writer in her own right, whose favorite themes—Jews and power, Jews and history, Jews and other Jews—make her a perfect pugilist for Grade. And so, just in time for Tishrei, we have what ought to be required reading for the Days of Awe, Wisse’s new translation of Grade’s My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner.

How to introduce the book? Best to begin in medias res: The narrator, also named Chaim, is sitting on a bench in Paris, all watched over by Moliere, Voltaire, and the other dead eminences whose stony likenesses adorn the city’s Hotel de Ville. He is talking to an old schoolmate of his, Hersh. Or maybe “talking” isn’t the mot juste: The word Grade chose in the original Yiddish was krig, or war, an apt term for a conversation that spans, in no apparent order, God’s culpability in the Holocaust, the possibility of a sustainable moral code divorced of religious faith, Platonism and its discontents, the nature of forgiveness, the rhythms of Jewish history, and other existential quandaries that can’t possibly be resolved in any one conversation—or one short story.

Chaim and Hersh were both students in a Yeshiva run by stringent rabbis who believed that life was best lived in a state of perpetual purification. It was the sort of place where you got in trouble for owning a comb, because caring about your appearance was a sign that you might be veering away from the singular dedication to moral self-improvement that was the only path a Jew ought to take in the world. Chaim couldn’t take it; he abandoned the school and Orthodoxy alike, became a famous writer, and spent the Second World War safely in Russia. Hersh stayed put, stayed faithful, survived a Nazi death camp, and ascended to become the head of a Yeshiva of his own.

As the two old friends continue their long-lived argument—the story gives us two brief vignettes, one from 1937 and the other from 1939, before settling down in postwar France for the showdown—one of Hersh’s students walks by and spots his rebbe. His name is Yehoshua, and he walks onto the scene like Ilsa sauntering into Rick’s Café Americain, a two-legged catalyst for urgent moral choices. Quickly, for Grade is artful with short sentences that contain multitudes, we learn that Yehoshua had survived the Holocaust in large part thanks to Hersh’s selflessness. Eager to defend his teacher, the boy joins in the quarrel, but, lacking Hersh’s mental agility and eloquence, he simply berates Chaim for failing to see that fervent sacrifice in service of Hashem is the one true path a Jew must take.

Prior to Yehoshua’s arrival, Chaim is so mild-mannered in his counterattack that readers could be forgiven for wondering if the conversation they’re witnessing is actually taking place, or if it’s some postmodern bifurcated monologue unfurling inside the author’s head, with both characters representing two sides of an argument Chaim is having with himself. But when provoked by Yehoshua’s harangues, the writer rises and delivers a rebuttal for the ages.

“My friends in my writers’ group—those in the Vilna ghetto who survived—they did risk their lives for their writing,” Chaim roars. “And they also put themselves at risk to rescue the manuscripts of great writers of the past. I’ll go further: you risked your life for a Sefer Torah, but you wouldn’t have done so for secular books. Maybe you didn’t approve of the Germans burning them, but you yourself would have burned them if you could. I understand now! My friends saved Jewish sacred texts, rare volumes, with the same devotion as Herzl’s diary and a letter from Maxim Gorky.”

What have we here? Read it once, and it’s a reboot of a conversation practically all of us have had at one point or another (read the brilliant Dara Horn recount hers here), likely late at night and with the aid of some schnapps, about the true meaning of being Jewish. Do those of us who warm themselves exclusively by the fire of the Torah have the upper hand? Might they claim a deeper, stronger, more essential bond to the pulsating truths that have been the faith’s beating heart for millennia? Or might the Jews who, for lack of a better term, call themselves secular argue that Saul Bellow and Steven Spielberg and Leonard Cohen, et al., are all the proof we need that the spirit of Jewish genius continues to grapple with the big questions of existence long after it has fled the airless quarters of the yeshiva and the letter of the law? Or is this dichotomy, at least as old as the Talmud, a silly one that ought to be retired?

This is not so much a public debate as a deeply intimate one, which is why it’s such a pleasure to witness Chaim and Hersh sounding so much alike even as they deliver radically divergent lines. The question at hand is the one we ponder each year come Elul, the question of our own path to teshuvah, or repentance. Almost comically for a religion not shy about codifying literally every other minute aspect of human life, Judaism leaves the business of heshbon nefesh—literally meaning the accounting of the soul—to all of us to figure out on our own. How do we repent? That depends on what we believe it is we ought to repent for, and what that might be is for each of us to decide.

But take a step back, and the story grows bigger, more radiant, more infused with the spirit of Ruth Wisse. At the very end of her introductory essay, Wisse called Grade’s story “an act of war, a subdued victory lap on the blood-soaked battlefield of Europe.” Go back and read it again, and you see exactly what she means. Pay special attention to how Grade advances the plot from 1939 to 1948: “Nine more years passed, years of war and destruction.” That’s it. Nine words is all the Holocaust merits, no more than a footnote to a much more fundamental, ancient, and eternal story, the story of the Jewish people.

“The Holocaust was a German initiative,” Wisse notes in her introduction. “It cost this story’s two former yeshiva classmates their families, their wives and parents, their friends, and their native communities: they could never recover any of what they had lost. But what did it really have to do with them and their krig? Grade’s audacious response is—almost nothing.” As Europe lay broken and bleeding, two Jews—scarred but far from defeated—are having exactly the same conversation they had begun long before the Nazis marched to power. And by continuing their private krig uninterrupted and unperturbed by the attempt on their lives, Chaim and Hersh win the larger war, the war history’s benighted barbarians wage against the Jews with alarming regularity and with gleeful ineptitude. Go ahead and try to kill us, Chaim and Hersh suggest with every eloquent exchange: It’ll only end with your empire in tatters and with us engaging in what has always kept us apart and alive and above it all, in that vigorous warlike argument about how we must live having, through no fault of our own, been singled out by God to be his chosen children.

This war is our superpower. As long as we engage with it, as long as we don’t abandon it—and ourselves—for the fleeting validations of a flimsy world that doesn’t much care for us, we’ll thrive. This war gives us meaning. This war makes us stronger. This war helps us define and carry out our mission in this world, the one for which we’re so consistently reviled, the mission of reminding the nations that man is more than beast and that God’s laws command us to search ourselves, improve, and wash all of the world’s dark corners in light. This war never ends.

And neither, really, does the story. No conclusion is reached, no resolution materializes. The sun sets. Chaim and Hersh grow weary. They rise from their bench, and in what ought to be the greeting each of us extends to his or her own Hersh Rasseyners, Chaim says: “May we both have the merit of meeting again in the future and seeing where we stand. And may I be as Jewish then as I am today. Reb Hersh, let us embrace.”

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.