The Subterranean Brilliance of Rutu Modan’s ‘Tunnels’

Israel’s leading graphic novelist excavates the conflict-ridden landscape of her country, with a hat tip to Indiana Jones

Israeli Eisner Award-winner artist Rutu Modan draws graphic novels about the stuff that Israeli existence is made of. Her debut, Exit Wounds, dealt with the clash between normal life and the terrorist attacks that the country experienced daily during the early 2000s. Her second graphic novel, The Property, dealt with the generation gap between young Israelis and their Holocaust-surviving relatives. 2020 saw the publication of Tunnels, her new and most ambitious work (recently acquired by Drawn & Quarterly), in which she takes upon herself to tell the tale of the seismic currents that run below the country’s surface.

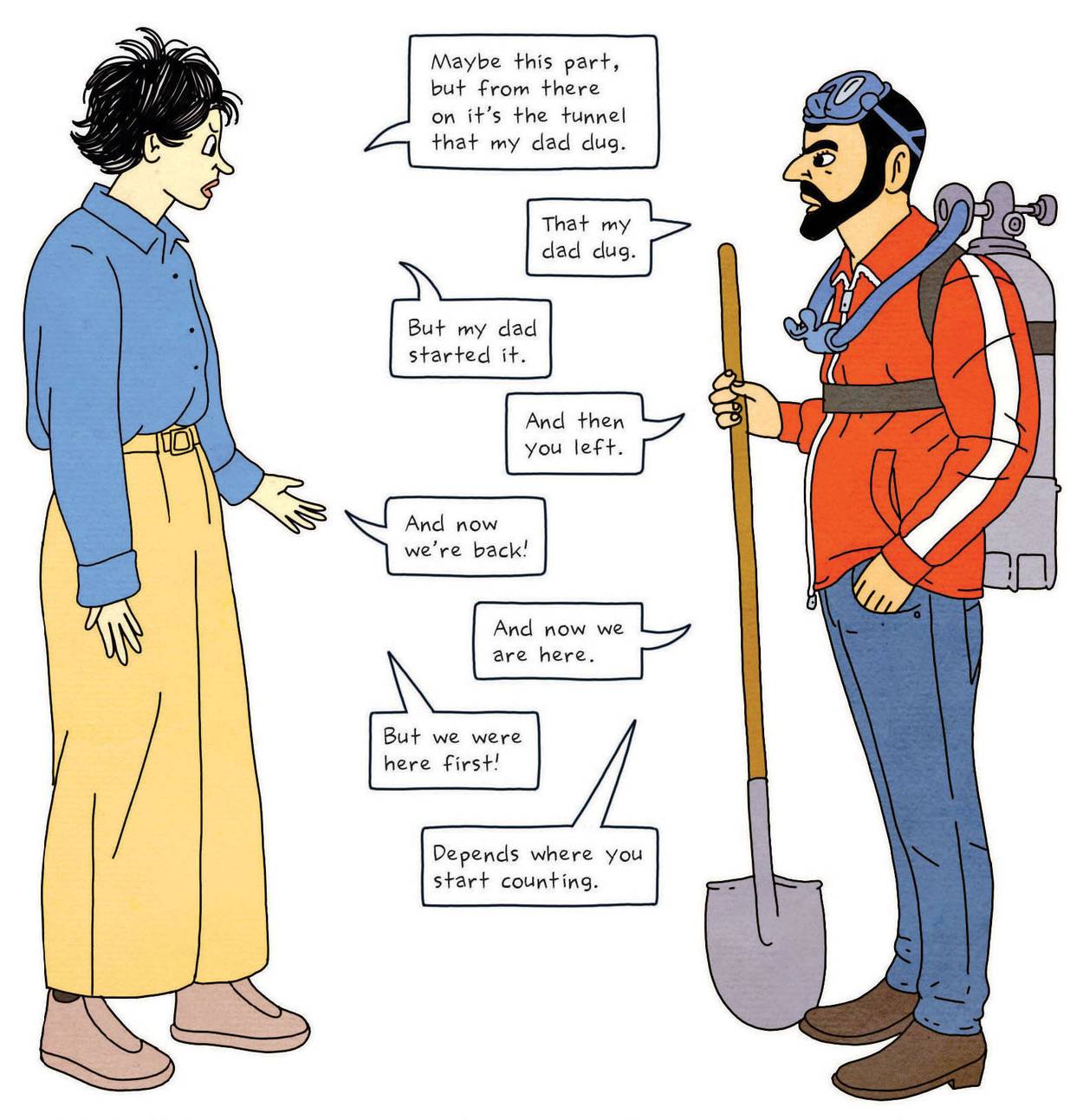

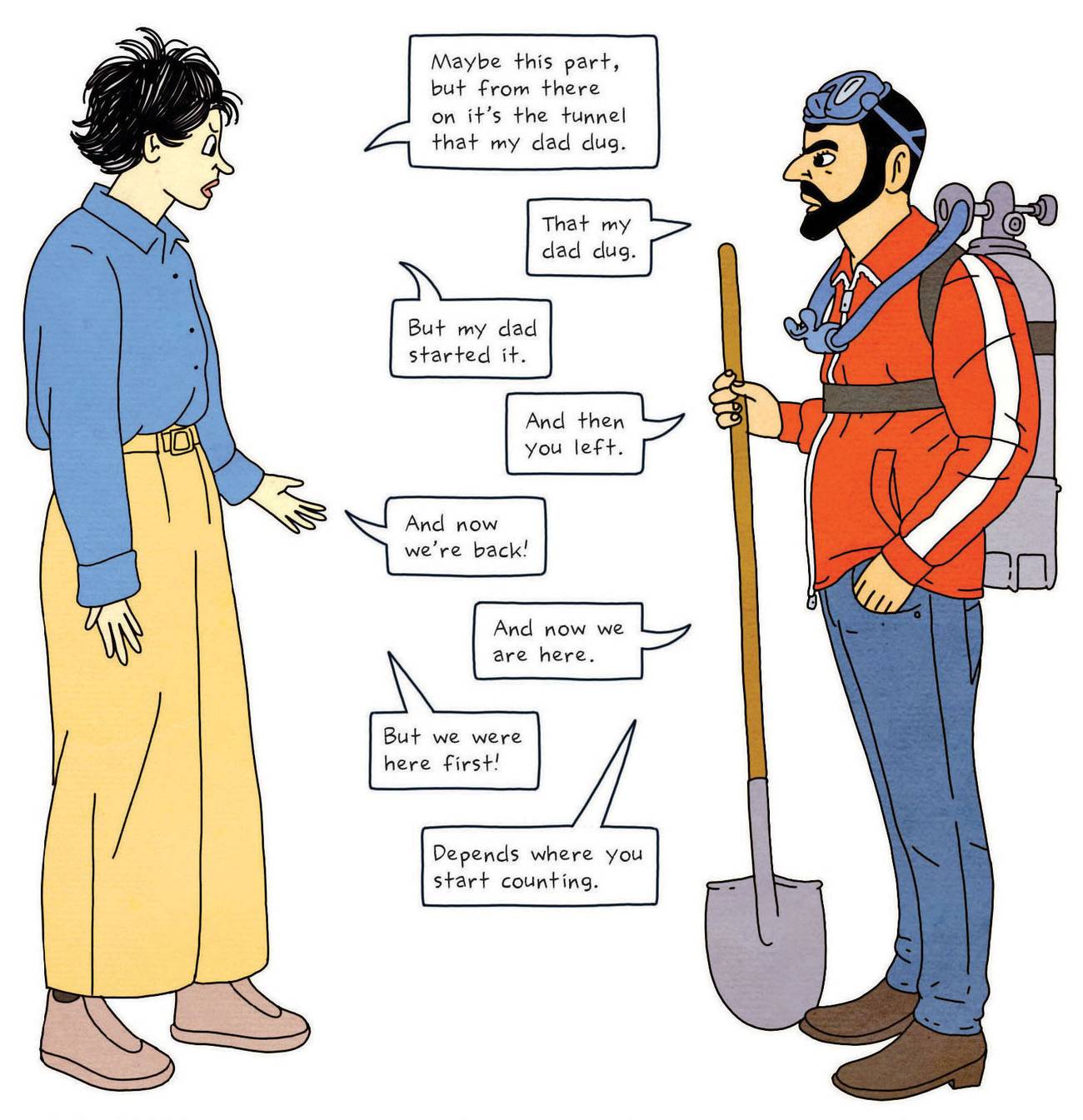

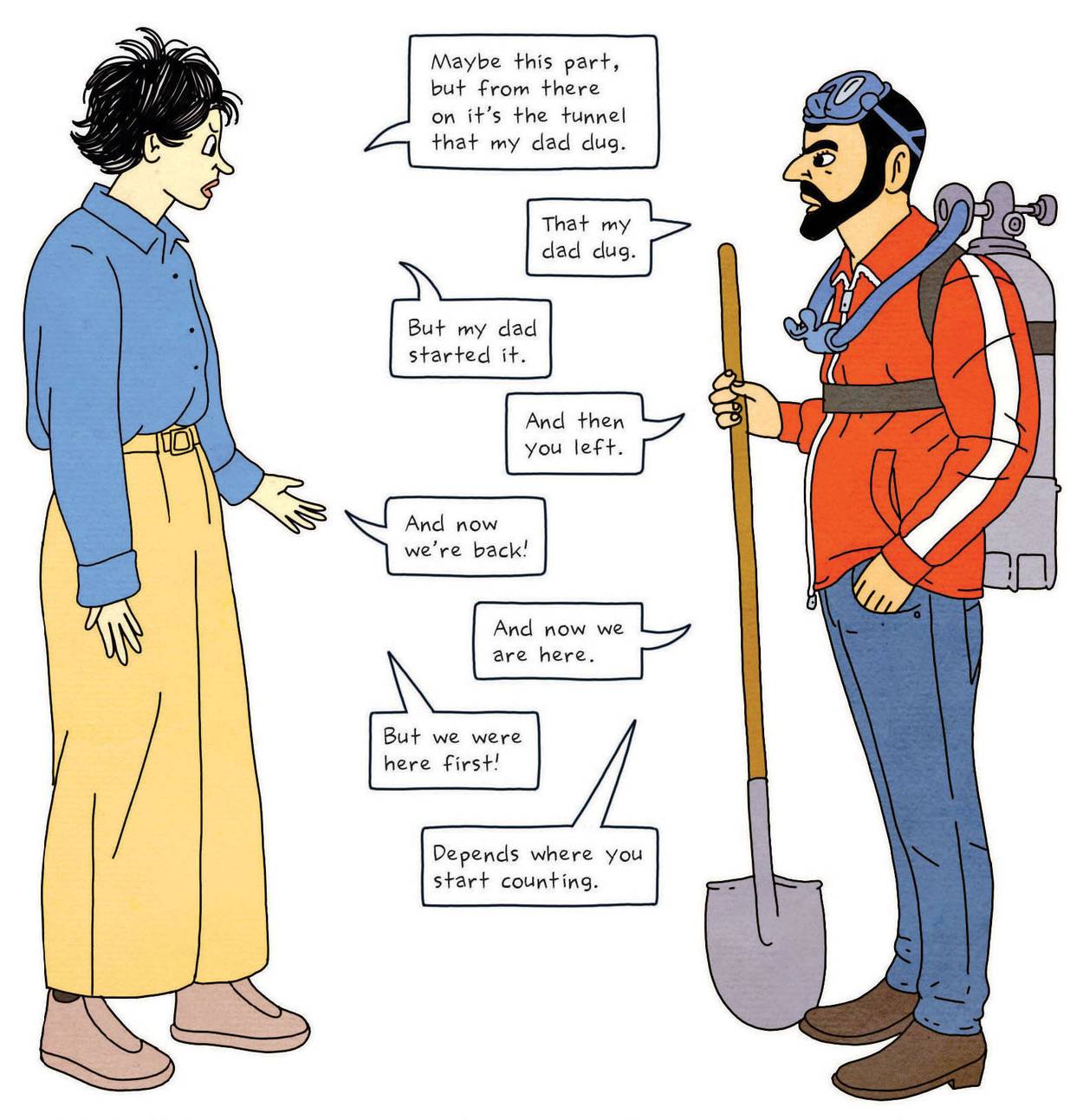

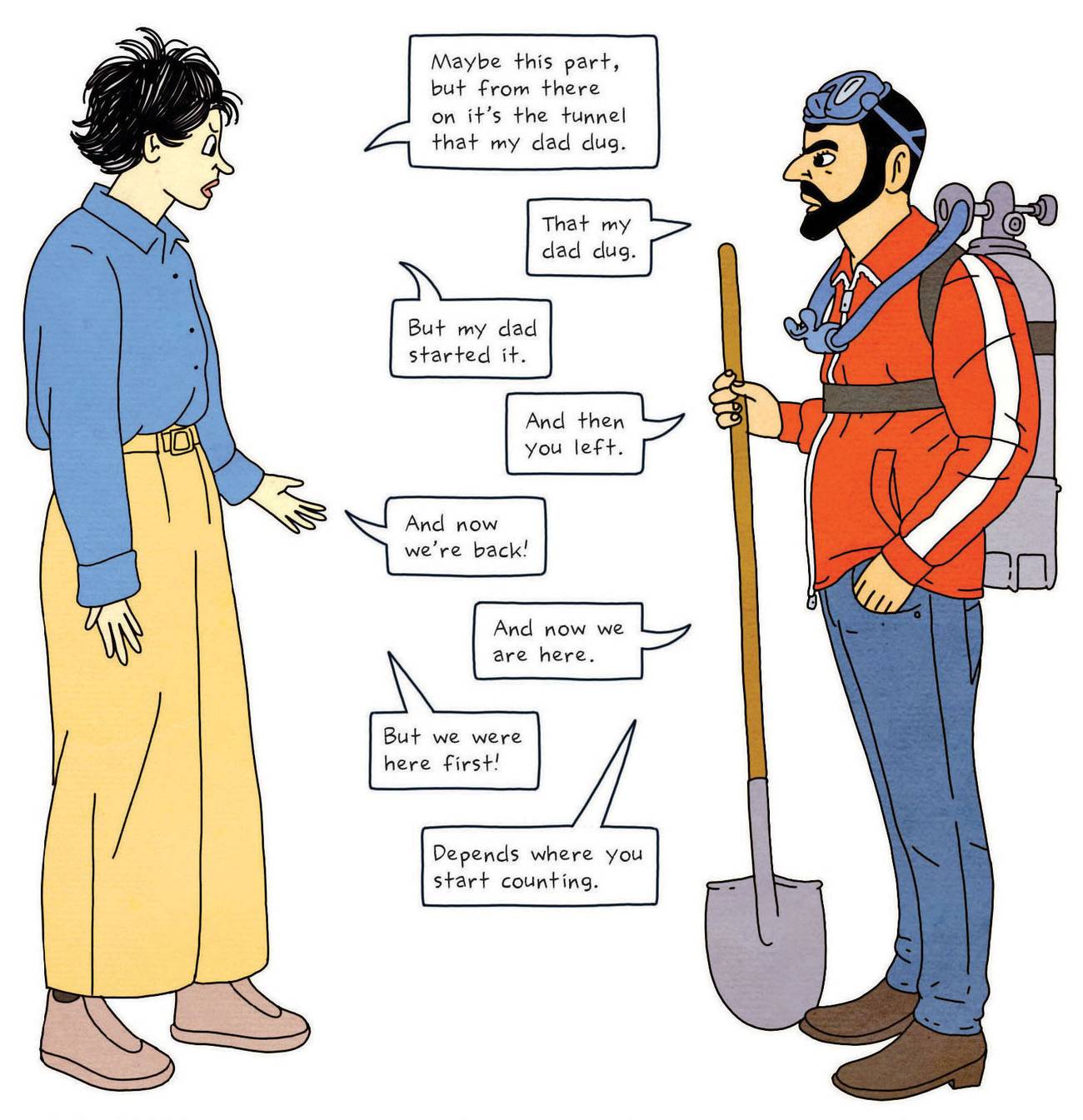

The novel’s core plot tells of Nili and Broshi, children of a renowned Israeli archaeologist who now suffers from dementia, who find themselves on the opposite sides in a struggle for what might be the greatest archaeological discovery in the world—the Ark of Covenant. While Nili, a single mother with broken dreams, wishes to find the Ark for the sake of her father’s legacy (and her own), Broshi wishes to find it in order to finally achieve a position within the academic community, even if it means collaborating with the professor who stole his father’s works. And since the speculated location of the Ark is somewhere between the Israeli and Palestinian territories, many people from both sides—from opportunistic parties to religious fanatics—are soon drawn in.

The story openly invites comparisons to Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, but as the plot progresses, it feels more like a comedy of the absurd rather than a grand adventure story. In fact, another cinematic masterpiece has stronger echoes in Tunnels—Joseph Cedar’s 2011 comedy-drama Footnote. As in Cedar’s film, Modan’s book shows how Jewish tradition is often degraded in modern Israel for the purpose of gaining money, land, and fame.

Among many such characters in Tunnels are an antiquities collector who cares only about the value of historical Jewish artifacts, an Orthodox Jew who sees the discovery of the Ark as means for eternal Jewish control over Palestinian territories, and a greedy archaeologist who sees it as nothing more than a path to recognition and acclaim. And when so many people—Israelis and Palestinians—want a piece of the land, things are bound to end with an explosion. Yet despite underlining petty and self-interested motives on all sides, Tunnels also portrays its characters in a sympathetic light: Can readers really quarrel with a woman’s quest to reclaim her father’s heritage, or over a Palestinian’s negative attitude toward Israelis after witnessing the treatment of his people by the IDF?

The main setting for the story is the endless web of tunnels that gave the novel its title. Modan visualizes these tunnels in the most unromantic way imaginable: They are mazes of sand and dust, with every new turn revealing sights that are depressingly similar to those seen before.

Modan’s tunnels do not hold rare treasures. Rather, they contain tools of destruction to further the never-ending conflicts that take place above ground. And what are these conflicts really over? Some ugly hills surrounded by a military fencing? The crumbling offices of a university where studies of antiques nobody cares for take place? Modan’s world is therefore about as far from the world of Indiana Jones as one can imagine.

The design and narrative of the characters feels equally out-of-place with the grand adventure that Nili imagines her quest to be. These characters represent a wide spectrum of the Israeli society: from the second-generation children of a once-great researcher who know they’ll never live up to his legacy, to the religious fanatics among both the Jewish and Arab populations, to a child who has found the perfect way to deal with the routine madness of the area—he just buries his head within his mother’s smartphone and asks everyone to leave him alone.

Graphically, Modan has based the appearance of the novel’s characters on known Israeli actors, and she includes a “list of credits” naming those actors at the beginning of the book. For readers familiar with Israeli culture, this adds an extra layer of meaning—knowing, for example, that actor Dov Navon who Modan “casts” as the neurotic archaeologist Motke is often typecast as this very kind of character in his television roles.

If there is one fault with Tunnels, it is that while Modan does bring things to a roaring climax by the end of the novel, she also defuses the situation a little too quickly. The novel’s ending carries the notion that all it takes is a simple crisis involving people in need to get all the novel’s warring parties to come together and help. It is a comforting subtext, but it feels a bit forced. In reality, the conflicts will continue on.

Other than that, however, Tunnels is a great triumph—one which deserves to be recognized as one of the best works of Israeli literature in 2020.

Raz Greenberg, an animation researcher, is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator.