Salman Rushdie’s New Novel Is Stuck in the ’90s

In the best ways, and also the worst

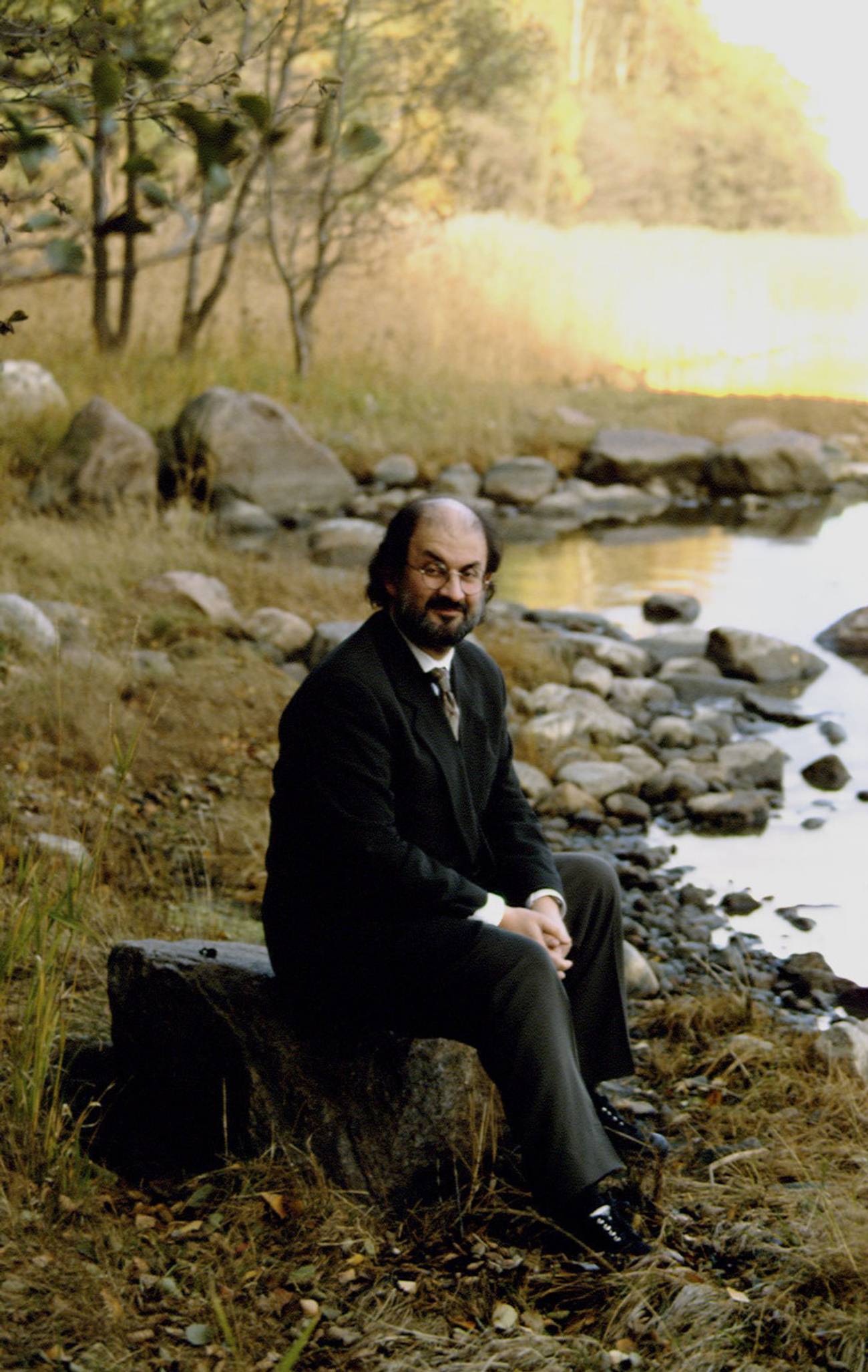

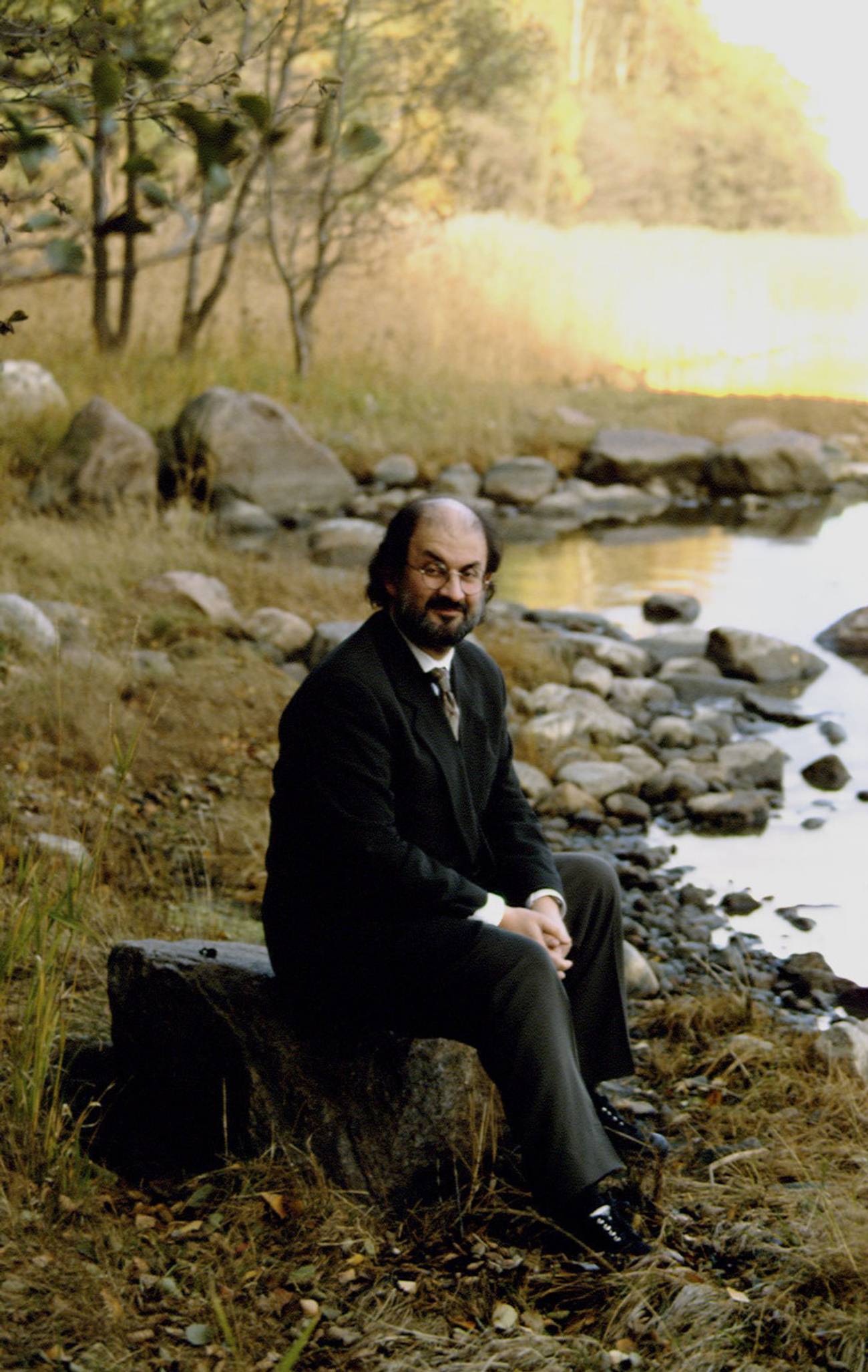

One fatwa, three decades in varying degrees of hiding, 21 books, 15 stab wounds, a murdered translator, and an appearance on Curb Your Enthusiasm later, Salman Rushdie has not lost his innocence. Rushdie’s new novel, Victory City, has a certain flinty fun to it. Written before an assassination attempt in western New York state by an American Islamist that left the author on a ventilator and cost him an eye, the pages are aglow with sorcery and forest monkeys of different colors and tales of palace intrigue. It also, as the story of the rise and fall of an empire and the political fortunes in between, contains Rushdie’s political philosophy—his theory of what makes a society work and what makes one fail.

That theory is this: Love will triumph if only we will let it, and it’s insane when we won’t. Can’t we all just get along? We would if demagogues would let us. In the absence of stupid ideas that mainly come from religion and of the self-destructive male impulse to try to make women belong to them like a bit of jewelry, things would get by quite well. “God is not the thing. Being able to rule ourselves is the thing,” a character says. Rushdie is, in short, a 1990s-vintage believer in open societies, liberalism, the twindom of reason and beauty, and probably of democratic peace theory too. He is scandalized by the fact that people display backwardness of the sort almost all people do, attaching their hopes to superstitions and bothering to care that other people worship different things and fuck in different ways, regarding it as a sort of predictable yet incomprehensible hiccup.

OK, boomer! But lots of trite things are also right.

Rushdie’s rollicking tale of state-building begins at the outset of the 1300s, when a young girl sees her mother burned alive along with the wives of a defeated army next to a river as part of a backward funerary ritual. This girl, Pampa Kampana, is our hero, and this moment is her psychic birth, the moment her conscience sets itself on creating a world in which never again will women have to suffer such horrors. “For the rest of her life Pampa Kampana, who shared a name with the river on whose banks all this happened, would carry the scent of her mother’s burning flesh on her nostrils.” It is also the moment she is touched by a goddess, imbuing her with the supernatural powers that will allow her to create a city out of seeds, to implant memories and a sense of self in its initial residents, and to live alongside the city for all of the 250 years during which it becomes the capital of the greatest empire on earth. The novel we read, in a bit of metatextual play, is supposedly a precis of the verse epic Pampa Kampana writes of her own lifetime, within the novel’s story itself, translated into modern prose and summarized by a narrator who breaks in from time to time with fun facts or with his own views on the historicity of the venerated writing like some Folger Shakespeare Library annotator.

But first, before she makes her city, Pampa spends her adolescence in a cave inhabited by a supposed holy man, a sage who abuses her. It is here that she meets the two brothers, Hukka and Bukka Sangama, cowherds by trade now dragooned into a life of soldiering, whom she gifts with magic seeds. They plant the seeds, and from them springs up an entire city “out of the rocks and dust,” complete with walled fortifications, a temple, market stalls, and bewildered new people, who have no memory and no history in their fresh-born home. Pampa must magically whisper generations of memories to them over the coming days for them to become its citizens.

Hukka and Bukka, with only herding and soldiering to draw on, must take up the task of ruling. The brothers, of course, turn their attention first to bickering over who gets which bedroom in the palace, and who gets first pick of concubines. They fall back on tradition to decide which should get to be king first: the older. But what else? What kind of place will they make out of nothing but the skeleton of a society, where the residents have no past? What is the good city? they begin to try to work out, like a pair of class clowns trying to remember the seminar on The Republic they slept through hungover. “Things are simpler for vegetables,” one says. “You have your roots so you know your place.”

They name their city Vijayanagar (a real-life historical empire with its ruins at the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Hampi, a long daytrip from either Bangalore or Hyderabad), meaning “city of victory.” It’s soon rechristened Bisnaga by a foreign pronunciation. The rest of the book follows Pampa the part goddess, part wounded girl trying to oversee its fate and guide it toward openness and equal treatment of women, and away from destruction.

The city’s first golden age, which takes place under the reign of the two brothers, is golden mainly because they don’t care enough about controlling people’s daily lives to be tyrants. They shrug at one another when they ponder whether their citizens should be circumcised. Hukka, the first ruler, is less interested in forbidding lifestyles and more interested in marrying Pampa Kampana, who is beautiful and whose supernatural powers include staying forever 20-something. (Leonardo DiCaprio would probably be intrigued, too.) Foreigners are welcome, the coffers overflow, and the empire grows.

With Pampa as queen, it becomes a pluralist paradise, a place “whose citizens loved everything beautiful, took pride in the glorious architecture rising up all around them, and rejoiced in poetry and in song; and who enthusiastically enjoyed the practice of sodomy as well as heterosexuality, many Bisnagans seeing no need to love only members of the opposite sex, and taking equal pleasure in the companionship of their own gender as well.”

But by now her sorceress’s whispers are not the only things playing at the minds of the people of Bisnaga. Her old tormentor, the sage in the cave, has introduced traditionalist religious ideas to the citizenry. Many of them, she finds, think a life of greater purpose will come from disallowing poetry and other ideas. “One person’s art is another’s dirty picture,” a royal adviser explains, laying out why some Bisnagans are unhappy even though the city now enjoys material plenty, including temples depicting sex in their statuary.

Pampa wants one of her three daughters to be the next ruler. She sees in her sons religious zealots who will ruin what makes her city great. Rushdie here tips his hand about what he believes: True magic is to be found among the literate and the urbane, people who love constantly creating new things over venerating the upkeep of old ones. Yet even if you make people from seeds and whisper their memories to them, so long as they are people, some of them just aren’t like that. “It may just be,” the king tells her in a remarkable intrusion of our era’s rubric about history having a right side which will inevitably win out, “that your ideas are too progressive for the fourteenth century.” In the ensuing secession crisis, Pampa and her daughters have to flee.

After a vivid middle section involving an enchanted forest, she must eventually return to Bisnaga. When she does, a lifetime has passed. Her face forgotten, she must live as an ordinary member of a city that is now changed, no longer her paradise of feminist equality and artistic openness. It has suffered “the victory of the humdrum, the mundane, over that other reality. The victory of a line of ordinary boys over that of extraordinary girls.”

I will not ruin the book by recounting in detail how Pampa Kampana deals with the next phases of the life of Bisnaga, and what happens when she tries to work her will in the city again over its next two dynasties. It is enough to know that she lives for 247 years (the age of Salman Rushdie’s adoptive home of America), and that in the end she is unable to save men from the kinds of mistakes that we seem to make inevitably: ones born from rage and seeking honor and feeling purposeless.

Though eternally youthful, Pampa Kampana is reduced to something like decrepitude when her eyes are seared out with hot pokers by a paranoid and ego-wounded king, in a series of passages that prefigure the author’s own life. (If Salman Rushdie did not exist, Salman Rushdie would have had to invent him.) Her story ends with her heroism defined not by her work as the founder of an empire, but simply as a writer. She tries to write her epic blind, and “her hand learned quickly, returned easily to the familiar relationship of paper and inkwell.” Yet it proves too hard. Blinded and rendered weak, she tenderly dictates to an unlikely friend. In the final passage of the book, with Bisnaga’s fortress finally falling in battle amid a clash of civilizations, her last act is to take her manuscript and seal it in a clay pot and bury it, to vouchsafe her work so that she may be read. Her last words are these: “Words are the only victors.”

And this brings us to the unavoidable extraordinary circumstances around this novel. This book is much better than recent Rushdie output such as The Golden House. Like Midnight’s Children, the breakout book of Rushdie’s career, it’s a look at an Indian empire’s birth, though setting it before the Enlightenment rather than after World War II keeps our own world further away, so Rushdie can worry more about human nature. It celebrates the tradition of ancient epics like the Ramayana, with nods to Romulus and Remus and to modern theater and to Western tradition.

And yet, stories are not completely in the power of their creators, and it is hard to read this book as a purely literary event. If the Islamic Republic of Iran’s ruling regime had not been so weakened by the Iran-Iraq War ending in 1988, a war that saw over a million casualties, it likely would not have had the domestic political needs that caused it to start a bizarre campaign in 1989 to murder the Indian-British novelist. There was a time when there was no end of Rushdie fatwa coverage. As novelist and Rushdie friend Martin Amis put it, after the fatwa, Rushdie “vanished into the front page.” He was conscripted as a living martyr to the cause of free speech, and less comfortably to the cause of Western politics around opposing radical Islam. But that time has passed. When Rushdie was actually nearly killed, there were barely any stories about it between the days after the attack and the release of this novel.

Rushdie’s political imagination seems to have calcified since he was put into what has been called his “internal exile.” From his third-person memoir Joseph Anton and as one of Rushdie’s fellow New Yorkers, one can learn about how he eventually stopped traveling with daily security and resumed something like normal life. But he never really left the psychic confinement of being hunted, where he has been stuck since the end of the Cold War. So that also means this book on state formation and the social ills that topple empires feels a bit stuck in a time when Tom Friedman was the celebrated author of The Lexus and the Olive Tree heralding the positive results of globalization to come, not the embarrassing columnist who ought to be fired for filing copy no thinking person can get through.

Victory City is a parable of the good city that contains little wisdom that is unavailable on MSNBC or at the Aspen Ideas Festival. The good city is good when it practices girlboss feminism and U.N.-style pacifism ensured by the goodwill of tyrants. It emphasizes negating rather than channeling the uneasy feelings of deplorable people who don’t feel at home in open societies. One of the strangest things about this novel is that it includes a sort of incomplete bibliography, a list of books Rushdie says he “read before and during the writing of this novel.” They’re mainly histories of the historical Vijayanagar, plus V.S. Naipaul’s India: A Wounded Civilization. None of the listed titles is about political theory, but I wrote down early that I thought he’d been reading Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson or possibly Ernest Gellner’s Nations and Nationalism, the two go-to scholarly books smart people tend to read about (postindustrial) societies and how they think of themselves as nations. The guiding idea is that nationhood is a fictive construct about history, but, by being a shared construct, it unites society in a quite real way. “It was necessary,” Rushdie explains of Pampa Kampana’s project to give false memories to Bisnaga’s citizens in the novel, “to do something to cure the multitude of its unreality. Her solution was fiction. She was making up their lives, their castes, their faiths, how many brothers and sisters they had …”

While I admire Anderson and Gellner, they are poor guides to why the most prosperous nations on Earth, from France with its National Front to America with its MAGAnauts, are beset by political movements curious about the martial virtues and traditional religion and a felt sense that things have gotten somehow worse as they have gotten objectively better, combined with the desire to restrict foreign influence. Orwell got it when he wrote in a review of Mein Kampf that “human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades.”

We have learned a lot since the 1990s about how the victory of liberal society can prove pyrrhic. Little of it seems to have impressed itself on Salman Rushdie. The people in Bisnaga or the 21st century who would regulate art and forbid other religions and disallow women’s education are people who just don’t get it. Haven’t they heard that kindness is everything? Haven’t they heard about empathy? When they spoil the party, it’s a sort of unaccountable tragedy. We can regret it, and we can write about it with powerful words. But that’s about it.

What the so-called “global rise of populism” associated with the period of Donald Trump’s presidency taught me was that we had better listen to people unlike us when they are unhappy. We had better try to make sure there is some democratic accountability for their wishes, so they don’t try to seek accountability in undemocratic ways—even if I can demonstrate with charts why their preferred solutions are stupid.

Yet for all the unreconstructed 1990s-ness of the boomer fable laid out in Victory City, it is more important to say that it is a good book. Also, there’s another, less pleasant, reason to read it. It’s possible this will be Rushdie’s last book, or the last one without an asterisk next to It. While Rushdie himself has been defiant, with his literary emissaries claiming he was joking as soon as the ventilator was out, one has to darkly wonder how weakened has the writer been, as a writer. I got minor ulnar nerve damage in 2021, and it did more than just hurt where the nerve connects in the arm; it messed with my mind, my memory, and made it nearly impossible to write anything substantial. Rushdie’s left ulnar nerve was nearly severed. We don’t know how sad the story is yet.

The crime of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was always a double crime: It was an attempted murder and also an act of censorship of anyone who wished to write anything that someone, anywhere on Earth, might think was worth killing for. That’s why it was always so chafing when people lent moral support to Iran’s supreme leader. They were complicit in the censorship, which is an ongoing crime—not just against Rushdie, but against us too.

Nicholas Clairmont is the Life and Arts editor of the Washington Examiner Magazine and a freelance reporter and writer. Follow him on Twitter @nickclairmont1.