Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Hebrew Poet

The Romantic poet’s underappreciated collaboration with the pioneering Hebrew scholar Hyman Hurwitz made him more of a Hebraist than most readers know

Two hundred and two years ago today, on Kislev 10, Nov. 19, 1817, the great English Romantic poet and famed opium addict Samuel Taylor Coleridge, author of “Christabel,” “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” and “Kubla Khan,” entered the Ashkenazi Orthodox synagogue in Aldgate, London. Age 43, Coleridge was not at his best. Impoverished, detached from his wife and his literary soul mate (“Wordsworth has given me up”), the poet was ready to “place himself in a private madhouse.” Indeed, he was hospitalized in friends’ households, first with John Morgan and his family, and later with James Gillman’s family in Moreton House, where Gillman—Coleridge’s friend, physician, and biographer—closely observed the poet’s narcotic habits.

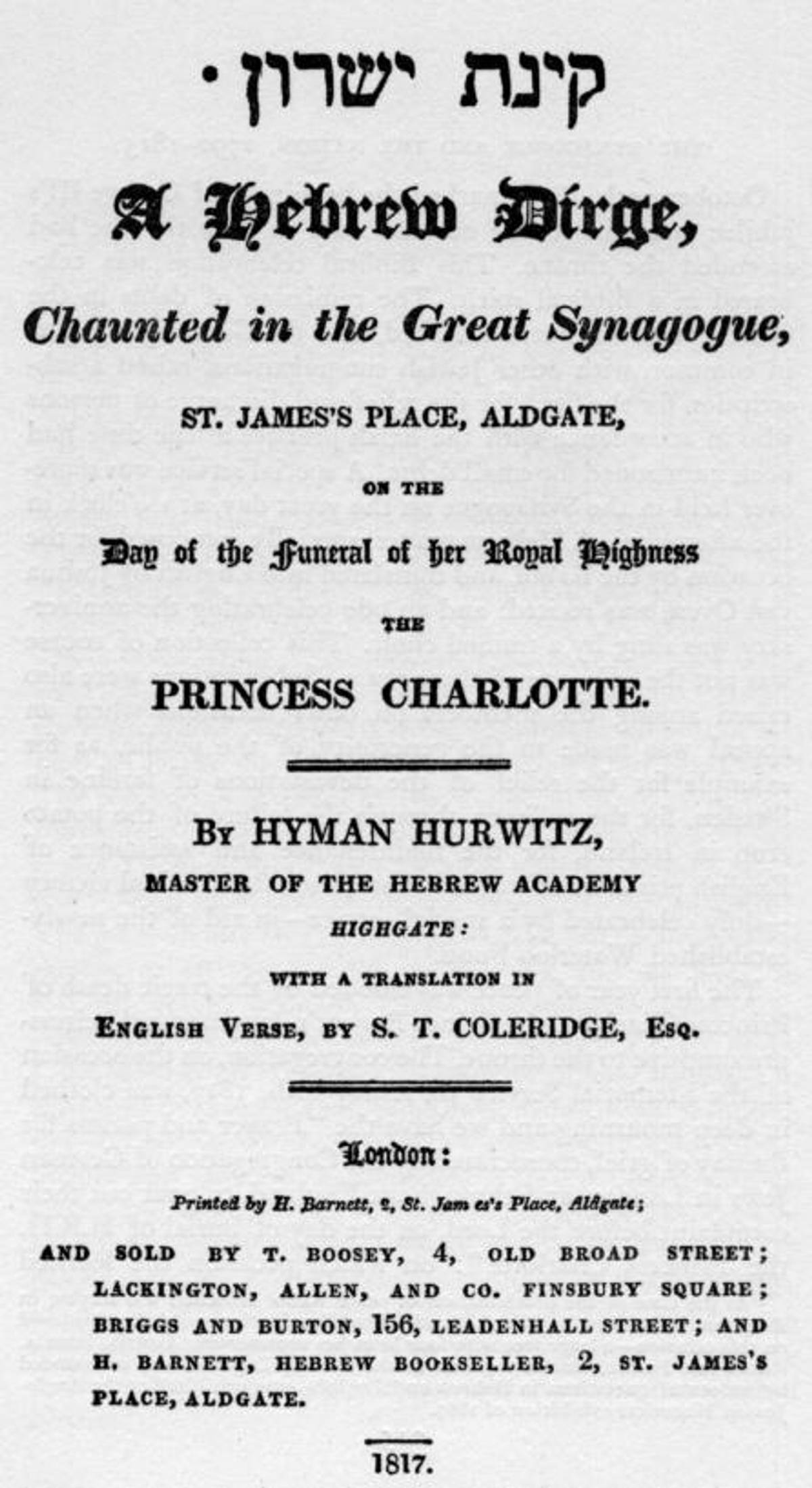

Two doors away, in Church House, 10 South Grove, lived Hyman Hurwitz, who would become one of the first professors of Hebrew in Britain. A year after moving to Highgate, Coleridge encountered Hurwitz, and for the next 20 years the two met almost every day and shared their work, until Coleridge’s death in 1834. The event that Coleridge was about to participate in at the synagogue was a performance of a collaboration by the two men, titled Kinat Yeshurun, a Hebrew dirge also known as “Israel’s Lament.”

Hyman Hurwitz emigrated from Posen, Poland, in 1796 and earned a reputation as a pioneering Hebrew scholar. He established a private Hebrew school for boys in Highgate, gave lectures attended by Moses Montefiore among others, advised Disraeli on biblical interpretation, and was considered a sophisticated original thinker, much more than any other Anglo-Jewish maskil. His first book on the fundamentals of the Hebrew language went through several reprintings and was translated into German and Italian. Hurwitz guided Coleridge in studying Sanskrit and Hebrew, and Coleridge helped him to publish and earn promotions.

Coleridge, who described Hurwitz as “the Luther of Judaism,” edited the preface to Hurwitz’s popular book Hebrew Tales, which made Talmudic homilies accessible to the English reader for the first time. The book opened with three homilies that Coleridge reworked from German. On Coleridge’s recommendation, Hurwitz was appointed as professor of Hebrew at the new University of London. He had the honor of overseeing the printing of the first Hebrew Bible in America, three years before “Israel’s Lament” was performed for the first time.

Like the reverberations of the death of Princess Diana 180 years later, the grief surrounding the tragic death in childbirth of Princess Charlotte of Wales, the only daughter of the crown prince, at the age of 21 spawned an abundance of popular works, of which Hurwitz’s lament was one. The lament was published in a form of a bilingual 13-page octavo pamphlet and appeared in several editions, perhaps as a symbol of the Jewish community’s covenant with the kingdom, as well as a Tory hymn:

Mourn, Israel! Sons of Israel, mourn!

Give utterance to the inward throe,

As wails of her first Love forlorn,

The Virgin clad in robes of woe!

The lament follows the ancient lament “Eli Tsiyyon ve-Areha,” which concludes the Ashkenazi liturgy for the Ninth of Av. Unlike the other laments for the Ninth of Av, which are sung in a common regular melody, “Eli Tsiyyon ve-Areha” is sung in unison while standing and has a tune of its own. “Israel’s Lament,” which was composed by Henry Bishop under the title “Mourn the Bright Rose,” on the basis of the tune of an ancient Hebrew lament described by Bishop as a melody “so interesting for its Antiquity, simplicity & impressive Pathos.”

The translation of “Israel’s Lament” from Hebrew to English was a collaborative enterprise, and both texts—the Hebrew poem and its English translation—were completed in a dialogic process. Coleridge recovered the Hebrew that he had learned at school, and Hurwitz was probably glad to discuss his poem with such a pupil. The explanations that Coleridge needed must have produced clarifications and improvements by both authors.

Coleridge strove intensively to adhere to the metric format of the original Hebrew work. The difficulty in translating Hurwitz’s dirge, he emphasized, “consists in the simplicity of the thoughts, well suiting a dirge and still more a Hebrew dirge: but for that reason hard to be translated into our compressed and monosyllabic language without one or other of two evils: either that translator must add thoughts and images, and of course cease to be a translator, or he must repeat the same thoughts in other words and become tautological.”

In his translation, Coleridge changed the character of the original lament considerably. He shortened rhyming lines, to make it less antiphonal, and universalized the biblical allusions. Jim Mays, the editor of the scholarly edition, concludes: “This was a back translation as much as translation.”

The collaboration was a huge and lasting success. In 1820, Coleridge and Hurwitz worked together once again. Hurwitz composed another lament on the occasion of the death of Charlotte’s grandfather, George III, and Coleridge again translated it into English. “The Tears of a Grateful People” [Kol Nehi] was printed in a bilingual Hebrew-English pamphlet and performed in the central synagogue of London on the day of the monarch’s funeral. As Karen A. Weisman shows in her recent book Singing in a Foreign Land (2018), both laments reflect how English Jewry identified with the British nation while at the same time draw attention to the group’s particularity.

The lament for George III, however, is perceptibly different in nature from the one written for Princess Charlotte. Whereas the main purpose of the former was to showcase the Jewish community’s participation in the nation’s grief, the latter was intended for the Jewish community itself, which had lost a father and a source of support. The translation of the earlier lament is directed to the general audience, whereas the subsequent work takes into consideration the circumscribed Jewish audience in the synagogue. Furthermore, while the princess had been received as the nation’s hope, George III (“the mad King who lost America”) was a more complicated case.

The dirge for the princess explicitly credits Coleridge as the translator; in the later lament he is camouflaged as a “friend.” The translator’s name may have been omitted due to the belief, widely held at that time, that the translation into English was inferior to the Hebrew original. Coleridge himself characterized his English translation as “free” and protested the fame and affection that it had received relative to his original poems: “Of this I am convinced, that a dozen such pretty, and so sweet and how smooth, well that is, charming compositions would gain more admiration with the English public than twice the number of poems twice as good as the ‘Ancient Mariner’, ‘Christabel’, ‘The Destiny of Nations’ and ‘Ode to the Departing Year’.”

Nor was the writing of odes of departed royalty part of literary fashion among Romantic poets. In an article by Percy Bysshe Shelley, “An Address to the People on the Death of the Princess Charlotte,” the poet protested the public rite of mourning that had enveloped the death of a princess who “for the public … had done nothing.” The fame and sympathy that the princess had amassed were contrasted with the silence that blanketed the deaths of thousands of anonymous birthing mothers and, particularly, that accompanied the execution for treason of workers who demonstrated. Shelley concluded his article by urging the English people to “follow the corpse of British Liberty.” Before George III’s death, Shelley vilified him in his sonnet “England in 1819,” as “an old, mad, despised, and dying king.” Likewise, Byron parodied the bemoaning of George III’s demise in his “The Vision of Judgment”: “He died! His death made no great stir on earth … All saved England’s churches are shamed … and synagogues have made a damned bad purchase.”

***

So how did one of the greatest poets in the English language learn Hebrew? Coleridge was in fact quite knowledgeable in Hebrew before he met Hyman Hurwitz. During his adult life, he set aside time for daily study of the Bible, used the Hebrew alphabet as a meditative tool, and treated what he considered the most poetic biblical book, Psalms, as a topic of daily conversation. He objected to interpreting the Bible as a record of historical events, instead seeing it as a fictional work that leaves important room for the imagination, the unconscious, and dreams, blending the concrete and the symbolic.

In his embrace of Hebrew, the poet followed in the path of his father, the Reverend John Coleridge, the great English Hebraist who wrote his dissertation on Judges 17–18. John Coleridge père considered the Jewish prophets to be important sources of political guidance, and he peppered his influential sermons with Hebrew. He was acquainted with Benjamin Kennicott, the great Hebrew scholar of the 18th century in England, and studied with senior members of the Exeter Cathedral chapter.

John’s son, Samuel, acquired the fundamentals of the Hebrew language during his term of study in Cambridge, even though his teachers were only “tolerable Hebraists.” He considered the Hebrew language “universally, permanently intelligible” and “appropriate to the divine purpose of the sacred scriptures” more than any other language, and he emphasized the basic, concrete, and sometimes visual meanings of Hebrew roots and their derivatives. For example, he noted the relationship among the Hebrew words adom, adama, and adam, and between qorban and qarov, as key to understanding them.

Coleridge’s poetry and thinking were strongly influenced by the Bible (especially Genesis, Judges, Isaiah, Jonah, Ezekiel, Psalms, Job, Song of Songs, Daniel, and more) and by other Jewish sources. talmudic and mishnaic homiletics and exegesis, Kabbalah, the creation myth, the account of the defeat of Jerusalem, the Wandering Jew archetype, the Abraham’s oak motif, and many others, all appear in his poems. A hundred years before Freud, Coleridge discussed in detail Michelangelo’s “Moses” statue in Rome as described in Exodus 32, commenting inter alia, “Horns were the emblem of power and sovereignty among the eastern nations and are still retained as such in Abyssinia.”

Coleridge adopted the philological method in biblical hermeneutics but disapproved of these intellectuals’ philosophical limitations. Following Protestant philosophers Robert Lowth, Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, Johann Gottfried Herder, and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Coleridge perceived Hebrew as a source and the Bible as a collection of fragments and poems united by the idea of communal experience. As such, he saw it as a model that struck a compromise between his attraction to broad genres (epos and drama) and his practice, in which narrow genres (lyrical poetry, ballade, hymn, and ode) are invoked.

Coleridge saw biblical poetry as a paragon and believed it helpful to compare it with classical Greek poetry in order to fine tune his theories about the nature of poetry and language, nature and imagination, the relationship between allegory and symbol, and the purpose of hermeneutics. In his works, he attempted to mimic Hebrew and the flexible Hebrew meter and used it as a source for genre invention and renovation. He was inspired by the diverse ways in which the Song of Songs can be read—as a drama, an allegory, a pastoral drama, “a series of lovely pearls strung on one thread” unconnected dramatically or allegorically, and “fragments” of “epic disconnectedness [that] resolves itself after all into unity” according to Goethe—and expanded on a dialectical (at once literal and allegoric) reading of the Song.

Coleridge also had direct experience in translating from Hebrew before he took up the translation of Hurwitz’s lament. He translated the first 10 verses of the Song of Deborah “in the parallelism of the Original” in a manner that displays a profound understanding of their levels of meaning. He translated (from German, using a Latin translation) four tales from the Talmud and Midrash. Dissatisfied with the Septuagint and the Vulgate, Coleridge produced a hexametric free translation of excerpts from Psalms, Isaiah, Job, and Micha, and intended to produce a double translation, literal and metrical, to more passages of scriptural poetry. Yet it was precisely his deep plunge into biblical poetry that motivated him to develop a theory about the impossibility of translating poetry (“untranslatableness”), for which reason he ultimately abandoned his translation program—one of many plans that he never fulfilled.

“No man of his time, or perhaps of any time … joined together more than Coleridge the reasoning powers of the philosopher, the imagination of the poet, etc. And yet, there is probably no man who, endowed with such remarkable talents, accomplished so little,” wrote Marcel Proust in “On Reading.” “The great defect in his character was the lack of the will to make use of his natural gifts. For all the massive projects constantly floating through his mind, he never made a serious effort to execute even one. … He preferred to come begging every week, without supplying a single line of the poems he had only to write down in order to free himself.”

As a result, Coleridge’s probing insights on biblical poetry are scattered across his letters and diaries and have remained, as he put it, “eggs (in the hot sands of this Wilderness, the world!) with Ostrich Carelessness & Ostrich Oblivion.” He found the beauty of biblical poetry inspiring but concurrently paralyzing: “I know myself so far a poet as to feel assured that I can understand and interpret a poem in the spirit of poetry. … Like an ostrich, I cannot fly, yet have the wings that give me the feeling of flight.”

***

Conversely, in the past hundred years Coleridge’s three main poems gained several translations into Hebrew: “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (1798-1797) has five Hebrew versions; “Kubla Khan” (1817), nine versions; and “Christabel” (1817), one. The first two Hebrew translations were produced in the first decade of the 20th century by Eastern European Jews who settled in the United States and joined a circle of Hebrew teachers: Akiva Fleishman and Simon Ginsburg. Both followed the norms of translation into Hebrew that were in vogue in the Haskala and the Hebrew revival eras: biblical Hebrew, mellifluous syntax, and fealty to the rhetorical model at the expense of accurate communication of content. Fleishman’s and Ginsburg’s translations “Hebraized” and “Judaized” for the purpose of enriching Hebrew literature.

The next translation of Coleridge into Hebrew was produced in the 1970s by Simon Sandbank, the dean of translators in Israel. Unlike his predecessors, Sandbank, an Israel Prize laureate for translation of poetry, winner of the Tchernichowsky Prize for translation, professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a member of the Hebrew Language Academy, retains parentheses in the source text and uses a lower linguistic register. Reuven Tsur’s translation of Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” was published in the 1990s. Tsur, the founding father of the cognitive approach, received the Israel Prize for literature and held a professorship at the Department of Hebrew Literature at Tel Aviv University. He not only translated Coleridge but also devoted a special book to the examination of “Kubla Khan” in the spirit of cognitive poetics. Ruth Blumert’s translation of the “Rime,” published in 2001, is the first Hebrew translation of this work that includes the epigraph and the argument in full. Assaf Inbari’s translation of “Kubla Khan” highlights the translator’s own original voice in 21st-century Israeli literature, connecting history, documentation, and fiction. My own translation of Coleridge’s “Christabel” was published in 2011. Additional translations of Coleridge circulate online and in self-published books by Avinoam Mann, Nahum Wangrob, Yishai Rosenbaum, Arye Stav, and Yaakov Shaked.

Yet in my interviews (face-to-face and by correspondence) with translators of Coleridge from English to Hebrew, I found that none of them knew of Coleridge’s own translations from Hebrew to English.

Just the same, Coleridge’s translations from Hebrew are not entirely unknown to the Hebrew-reading community. In a brief article in English, published in the Jerusalem Post in 1972, Harold Fisch, a professor of English at Bar-Ilan University, gave a brief presentation of Coleridge’s Hebrew and Jewish sources.

An additional reference to Coleridge’s oeuvre as a translator from Hebrew is offered by the writer and artist Benjamin Tammuz, who edited the literature column in the newspaper Haaretz and served as a cultural-affairs adviser at the Israel Embassy in London. Tammuz published a fictional letter in which a Jew in 19th-century London complains about Coleridge’s anti-Semitic rhetoric. One cannot excuse him on the basis of ignorance of the facts, Tammuz claims, because, “Not many years ago, in 1817, Princess Charlotte died and on the day of her burial a Jewish dirge called Israel’s Lament, written by the president of the Hebrew Academy, Mr. Hyman Hurwitz, was recited in the great synagogue on St. James Square in Aldgate. Who translated the dirge into English? Was it none other than our poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge?”

Lilach Naishtat Bornstein is a visiting scholar in the department of comparative literature at Harvard University and a Lecturer at the Kibbutzim College of Education. She is the author of The Song of Songs and Poetics of the Romantic Fragment, Who’s Afraid of Christabel? A Story of a Reading Group, Their Jew: Right and Wrong in Holocaust Testimonies, among other books. Her current project is a digital platform (ColHEBridge) to analyze Coleridge’s translations from Hebrew.