The Freud Rabbit

Sarah Boxer’s whimsical cartoon novel puts a bestiary of human frailty on the psychoanalytic couch

What to make of Sarah Boxer? She’s a reporter, an editor, a critic, and a writer of psychoanalytic comix. OK, psychoanalytic graphic novels, if you prefer. With her squiggly, hand-drawn words and seemingly childish images, she intertwines the whimsical and the profoundly complex. She can be playfully poetic, too, as in her 2016 suggestion in The Atlantic that the best way to conquer those long sentences of Proust’s voluminous In Search of Lost Time is to read them on your cellphone, in bed, on a nightly basis. “Your cellphone screen is like a tiny glass-bottomed boat moving slowly over a vast and glowing ocean of words in the night. There is no shore. There is nothing beyond the words in front of you. It’s a voyage for one in the nighttime. Pure romance.” And pure Boxer.

I don’t know where Sarah Boxer read Freud and his followers, but she clearly knows her stuff. She says in the introduction to In the Floyd Archives (2001) that she “grew up with Freud.” That book she dedicated to her “favorite Freudian”—her father—and it is now being republished with a new sequel, Mother May I?, which, yes, is dedicated to her mother. Boxer tells us more than once that she “does not hate Freud.” She also says he is family. She knows that one does not preclude the other.

Boxer does not hate Freud, but she does have a lot of fun with him, and sometimes at his expense. It was the founder of psychoanalysis, after all, who taught that “the joke will allow us to turn to good account those ridiculous features in our enemy that the presence of opposing obstacles would not let us utter aloud or consciously.” The title In the Floyd Archives was a riff on Janet Malcolm’s In the Freud Archives, which is the scandalous story of how the guardians of Sigmund’s legacy tied themselves in knots to protect the kingdom of psychoanalysis. As is often the case, overprotection is a good way to lose things—or as the king in the King and I puzzled, getting protected out of all one owns. Malcolm’s book was the story of a loony legacy—of foolhardy attempts to keep secret certain facts about Freud, who himself had revealed how humans betray their secrets with their bodies, their language, and their dreams.

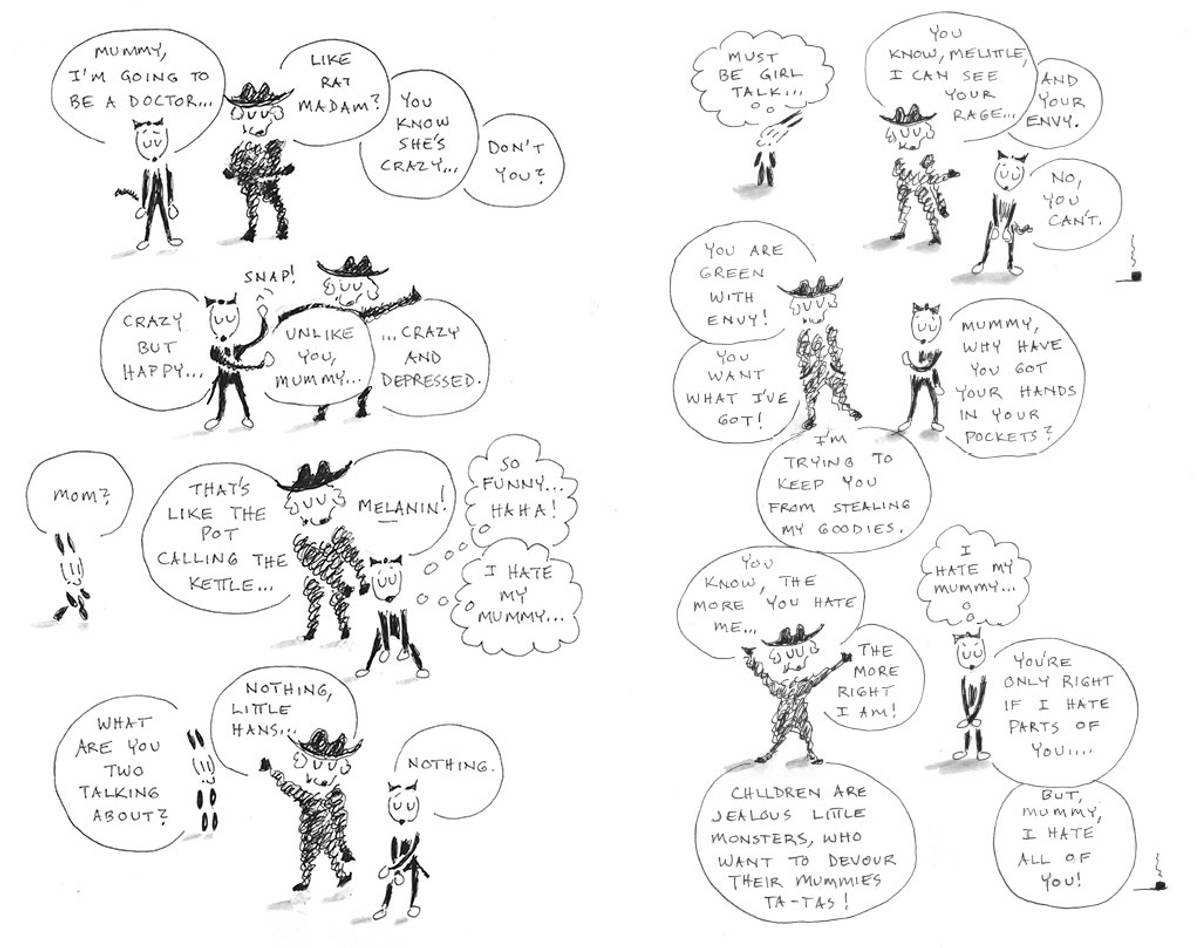

Both In the Floyd Archives and now Mother May I? picture the Freudian world through simple drawings of particular animals, each with its own neurosis. The books are bestiaries of human frailty. Boxer’s Freud is a bird named Floyd, a psychoanalyst who is treating other animals, each of whom is cleverly modeled on a famous case in the psychoanalytic canon. Floyd has sessions with Mr. Bunnyman, who quite sensibly is afraid of large animals (as was Freud’s Little Hans). Mr. Bunnyman is sometimes chased by Mr. Wolfman (another name from a famous case), who has an alter ego named “Lambskin” (viz. the case of Dora). The last animal in the bestiary is Rat Ma’am—who, like Freud’s patient named Rat Man, is always burying things and wondering what can be dug up to be buried again.

Rather than footnotes to help with the parallels, there are little pipes punctuating the drawings, cuing curious readers that they can flip to the back of the book to find references, quotations, even the odd drawing, from psychoanalytic sources.

In the Floyd Archives culminates with a snooze by Dr. Floyd and his patients taking the opportunity to steal away with the object for which they all long (in very different ways). Meanwhile the doctor dreams, and we see sketched out a condensed nightmare of the real Freud’s mistakes. Floyd awakes, though, feeling great. He is free of guilt, and of his patients. Since he is, after all, a bird, Dr. Floyd flies away, confirming his theory as he soars above us all that a dream is the fulfillment of a wish.

Back in 2001, Freud himself had recently been reburied by the psychiatric establishment, for the nth time. Psychopharmacology ruled the roost—Listening to Prozac had been published in 1993, and many thought treating us human animals with chemicals was going to be a lot more efficacious than the convoluted interpretations infamous in Freud-land. Boxer’s new comix, Mother May I?, is subtitled A Post-Floydian Folly because the comix adds some characters (and some lingo) from the Kleinian and “objects relations” school of psychoanalysis that was powerful in Great Britain in the mid-20th century.

Dr. Floyd and his animal patients are back—Mr. Bunnyman is still anxious, Mr. Wolfman is still wrestling with his alter ego, and Rat Ma’am is still wondering what to bury and what to give away. But now they are joined by an aggressive rabbit (Hans Klein), the black sheep Melanin Klein and her hostile daughter Melittle Klein, and the little pig Squiggle-Piggle (named for a game used by the British psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott in treating children). Melanin Klein, like her namesake Melanie, is all about the intense hostility that mothers (or parts of mothers) generate in their children. She sees herself and her theories confirmed, as did the real Melanie, by being detestable (at least in the eyes of her daughter). Somehow the characters find a way to gesture to what Winnicott called a holding environment, a place of affection—though they have to kill a totem figure to get there. Some object relations theorists stressed that parents shouldn’t aspire to being ideal—just good enough to create environments of affection and care so as not produce psychotic children. (We may choose to remember here that this volume is dedicated to the author’s mother.) “The people one deals with in real life,” Boxer notes, “are not the people they are to themselves but rather objects that play a specific role in one’s mind.” In her mind, these weighty psychoanalytic figures can play the roles of cartoon animals.

Sarah Boxer’s drawings are delightful, and she has completely internalized the psychoanalytic worldview that she satirizes. Freud stressed that humor, like dreams, “get around restrictions and open up sources of pleasure that have become inaccessible.” There’s plenty of pleasure to be found in Boxer’s books: She advises us to treat her comix like a dream, but she knows that is no simple matter. Still, we should “go with the flow,” she suggests, even as the patients take over the psychoanalytic asylum (or at least the consulting room). At the end of Mother May I?, Dr. Floyd is indeed dead, killed by one of his beloved (and loveable) patients. Bunnyman has to carry Floyd about—or at least what’s left of him. Boxer knows from Freud that the most powerful authority figure can be a dead one; the one we carry around in our heads. Her psychoanalytic comix are ingeniously playful reminders of how much we carry around, no matter how far we think we’ve moved on from the Freudian fantasyland.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Michael S. Roth, president of Wesleyan University, was the curator of the Library of Congress exhibition Sigmund Freud: Conflict and Culture. His most recent book is Safe Enough Spaces: A Pragmatist’s Approach to Inclusion, Free Speech and Political Correctness on College Campuses.