In November of 2018, at the National Arts Club in New York City, I attended a screening for the film Sobibor, which was described in the program as “First Russian Oscar Contender About Holocaust” (sic). The screening was part of a promotional campaign to secure a nomination in the best foreign film category, and was presented by the film’s producers, along with the Alexander Pechersky Foundation and the Russian American Foundation. Annexed to the auditorium where the screening was to happen was a small exhibition about Alexander “Sasha” Pechersky and the uprising he led at the Sobibor concentration camp, which was the subject of the film.

Konstantin Khabensky, the film’s star and director, had come to the screening from Russia. A panel of historians and experts was convened. The audience consisted of members of the local Jewish community and the Jewish press, not a few of them Russian-speaking. A group of elderly Russian Jewish war veterans, some in uniform, all decorated with their medals, were seated near the front of the room. Among them was a woman who wore a yellow star button on her blouse to identify her as a Holocaust survivor.

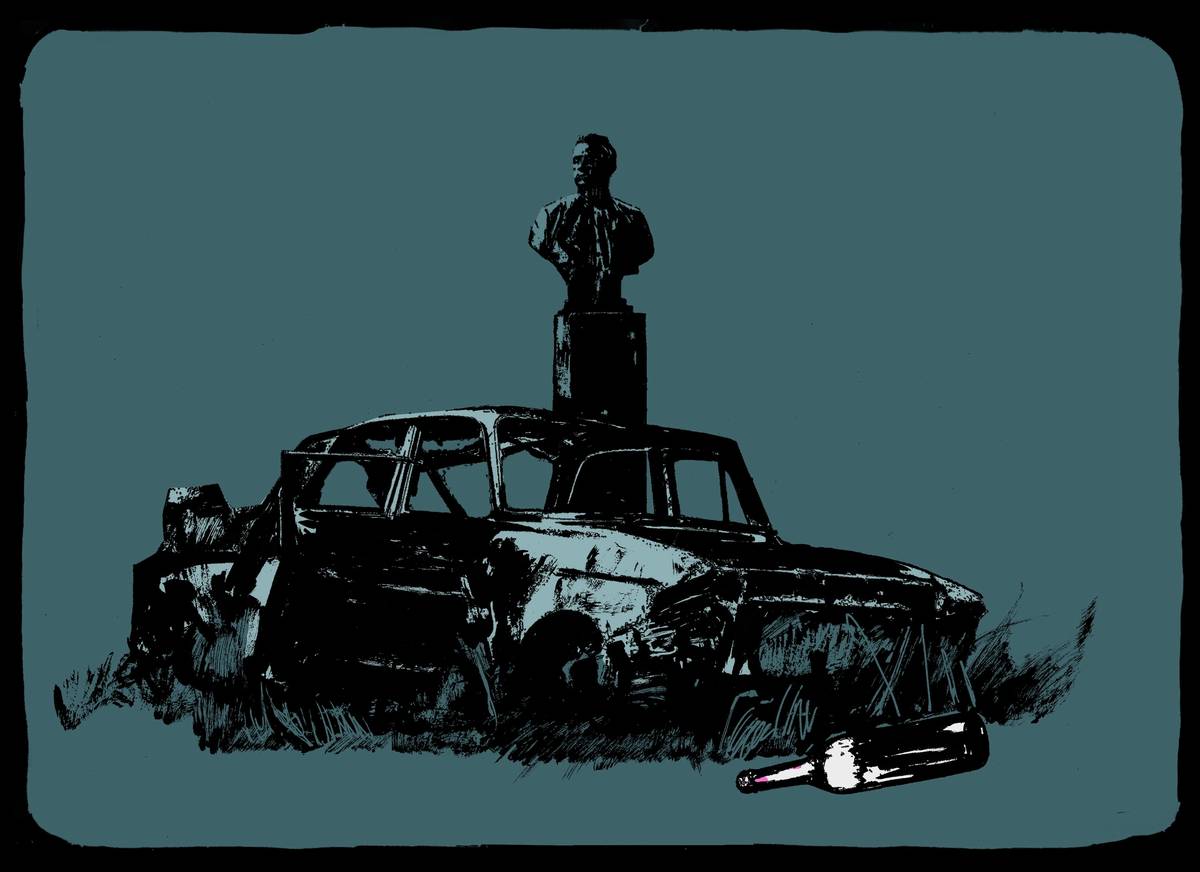

In opening remarks, a scholar of Soviet Holocaust cinema commended the producers for making a Russian film about the Holocaust, a suppressed subject for most of the Soviet period. In fact, any acknowledgment of the unique nature of the tragedy experienced by Soviet Jews in painting, sculpture, poetry, fiction, history, public monuments and other forms of remembrance was practically forbidden. In a nation that suffered so profoundly, with as many as 27 million citizens perishing during the war, the official position was that it was wrong to divide the victims. At sites of mass killings, if there was any commemoration at all, it memorialized “peaceful Soviet citizens” who had died at the hands of “the German occupiers.” Sobibor might therefore be regarded as the Russian equivalent to Schindler’s List.

Films are subjective things and it’s not my intention to engage in criticism of a film released two years ago. Also, the quality of the film is of negligible importance to the larger story of Alexander Pechersky’s life and legacy. But there were many people in the auditorium who were moved to tears by the film, gasped at acts of brutality or laughed at an incident of comeuppance against the Nazis, just like they were watching a regular movie. Unless they’d read the literature about Sobibor and Pechersky, none could have detected the places where the film departed from historical fact, though a partial list would include: Leon Feldhendler (spelled “Felhendler” in recently-discovered archival documents), one of the leaders of the camp underground, wasn’t killed during the revolt; Pechersky didn’t carry the corpse of a young woman named Luka out of the camp in his arms; a Nazi named Frenzel wasn’t shot by Pechersky; there was no crematorium smokestack in Sobibor; and Shlomo Szmajzner, a young Polish prisoner, didn’t, as the end titles assert, hunt down and kill Gustav Wagner, perhaps the camp’s most notoriously brutal SS officer, and 17 other Nazis in Brazil.

Photo of Sobibor from the report of Lieutenant Colonel Semion Volsky, August 1944 Central Archives of the Ministry of Defense, Russia

At the conclusion of the film, one audience member did inquire about historical accuracy, in response to which the gathered historians offered a general defense of the artist’s right to bend documentary truth for the sake of the emotional one. The Holocaust survivor, a small but pugnacious woman in the Russian Jewish mold, rose to praise the film, which she had now watched for the second time, though it caused her pain in every cell in her body. “Never again!” she proclaimed. One of the veterans took the floor and affirmed that the film showed what had happened in his generation and hoped it would serve as a lesson for the future. He proceeded to make some observations about Arab aggression and, after meeting with a mixed response, resumed his seat.

Nobody in the audience subjected the film to the kind of scrutiny it met in the more exacting corners of the Russian Internet. A widely circulated op-ed written by a commentator on Garry Kasparov’s website accused the filmmakers, and by extension the Russian state, of evading the truth about Sobibor and the heroes it pretended to celebrate: Where was the reference to the Soviet citizens who filled the ranks of the camp guards? What of the local population’s complicity with the Nazis? How about the Soviet Union’s merciless attitude toward its own POWs? And might they have spared a word about the tribulations Pechersky experienced after the war on account of both his captivity and his ethnicity?

While it can be easily argued that most of these points fall outside the parameters of the story of Sobibor and the revolt, it could also be argued that if the end titles could include false information about Nazi-hunting in Brazil, they could have included correct information about how Pechersky’s life unfolded after October 1943. But to understand why the film took the form it did, it is necessary to ask a different question, which is why, after so many years of disregard, the story of Pechersky and Sobibor received the financial and political support of the Russian state at all. Russia, like any country, has no shortage of neglected and forgotten heroes. So why Pechersky and why now?

The answer to this question boils down to an ecosystem of Pechersky revivalists—intellectuals and historians—mostly but not exclusively Russian, who have been working over the past decade to nudge Pechersky and Sobibor back into contemporary consciousness. The Russians in particular have delved into newly accessible Soviet archives and debunked myths that have long adhered to Pechersky. Unsurprisingly, all these people don’t share exactly the same view of Pechersky, and there is among them some amount of professional rivalry.

The commonly agreed upon facts of Pechersky’s life include the following: On Oct. 14, 1943, Alexander “Sasha” Pechersky, a Jewish Red Army soldier, led a revolt at the Sobibor death camp, which was located, like all other Nazi German death camps, in Poland. During that revolt, prisoners armed mainly with axes and knives killed 12 SS officers and several guards before overcoming barbed wire fencing and crossing a minefield to reach the surrounding woods. Of some 600 prisoners in Sobibor at the time, approximately half took the opportunity to escape. Fifty-seven survived to the end of the war. Their leader, Pechersky, was one of them.

Practically from the time of the revolt until his death in 1990, Alexander Pechersky devoted himself to trying to inform the world about Sobibor. But for reasons both calculated and circumstantial, the existence of the camp and the facts of the uprising remained largely unknown. Today, there remains considerable disagreement about the facts of Pechersky’s life in part because he was disinclined to write or speak about aspects of his biography not connected to Sobibor, in part due to gaps in the archival record, and in part due to people’s tendency to interpret the existing facts subjectively, in line with their own inclinations and beliefs. In other words, Pechersky has come to mean different things to different people. Was he fundamentally a Soviet, a Russian, a Jewish or a universal hero?

To even approach the question demands that one possess an understanding of what Sobibor was and how it came to be, as well as an adequate grasp of the peculiar and erratic social and political conditions in the Soviet Union during Pechersky’s lifetime, before, during, and after the Second World War, especially as they related to Jews.

Pechersky represents, as well as anyone, the complications and contradictions of the Soviet Jewish character, which remains little understood by people in the West. Of course, ignorance about the predicament of Soviet Jews isn’t as distressing as ignorance about the Holocaust—although the two are related. Recent polls and studies suggest that people, particularly the young, don’t know nearly as much as one would hope. In Moscow, I was told about an apparently well-known example of this: Some girls in provincial Russia, when asked by a television program if they knew what the Holocaust was, confused it with the name of a wallpaper glue.

Before I was 6, growing up in what was then the Soviet Union, I knew that in the forest behind our apartment complex in Riga, where we went cross-country skiing in winter, Germans had shot Jews. I knew what fate awaited my Latvian grandfather and my Lithuanian grandmother had they not left their shtetls before the Germans arrived, and what almost certainly would have become of my father, not quite 6 years old in the summer of 1941, had his family not boarded one of the last trains out of Daugavpils for Russia. For Soviet Jews of my generation, though born decades after the fact, it doesn’t require a big mental leap to imagine how one might have never existed.

Nevertheless, I knew almost nothing about Sobibor. I didn’t know, for instance, that along with Treblinka and Belzec, it had been created as part of Operation Reinhard—named for Reinhard Heydrich, one of the main proponents and architects of the Holocaust. According to Yitzhak Arad—whose book, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, provides the most thorough account of this facet of the Holocaust—these camps were intended for the annihilation of the Jews of the General Government, the eastern part of occupied Poland that the Nazis didn’t annex to Germany. Home to an estimated 2,284,000 Jews, the General Government included the districts of Warsaw, Cracow, Lublin, Lvov, and Radom. The decision to implement the plan was taken at the notorious Wannsee Conference in late January of 1942, and it was meant to be fulfilled by the end of that year.

Even more than Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Operation Reinhard death camps were the apotheosis of the Holocaust. Unlike Auschwitz, which provided slave labor to various German industries, the sole purpose of the Operation Reinhard camps was the rapid murder and plunder of Jewish men, women, and children. (Gypsies were also targeted for extermination, and it is believed that some several thousand were murdered there.) Within hours of arrival at these camps, the people would be dead and anything of value they had with them—including the women’s hair—would have been sorted for shipment to the Reich. A large gasoline engine piped carbon monoxide into as many as six or eight gas chambers, each with a capacity of 50-80 people. The dead were removed by the Sonderkommando, a squad of enslaved Jewish men, who searched the corpses for hidden valuables before depositing them into pits and, later, onto large grills made from railway tracks for cremation.

The death camps were designed not only for maximum efficiency, but also to spare the rank and file SS the distress associated with the mass shootings they had been conducting in the Soviet Union after the German army invaded. Ultimately, not just Polish Jews but Jews from all over Europe were murdered in the Operation Reinhard camps, most significantly from Holland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Germany, France, and the Soviet Union. Himmler issued no written orders about the camps at all. In remarks to high-ranking SS and police officers in 1943, he characterized the “annihilation of the Jewish people” as “an unwritten and never-to-be-written page of glory.”

Of the three Operation Reinhard camps, Sobibor was the most remote and the least known. This remained true after the war, as there were so few survivors. In the preface to his memoir, From the Ashes of Sobibor, Thomas “Toivi” Blatt, who’d been a young teenager in Sobibor, recalled giving an early draft of his manuscript to a “well-known survivor of Auschwitz” and being told that he must have “a tremendous imagination” since the man had “never heard of Sobibor and especially not of Jews revolting.”

Up to his arrival at the camp, there was little in Perchersky’s biography to predict that he would lead a revolt, or become a figure on whom national narratives would be hinged. He was born in 1909 in Kremenchug, Ukraine, in the Pale of Settlement, the third of four children to Aron and Sophia Pechersky. His father was a lawyer and his mother a homemaker. In 1915, during WWI, for reasons that aren’t entirely known, the family relocated to Rostov-on-Don, which at the time was one of Russia’s most cosmopolitan cities. Jews had resided there since the early 19th century, and the city also had a sizable population of Ukrainians, Armenians, and Greeks. Relations between the various ethnicities were generally harmonious, although Rostov experienced the same convulsions as elsewhere in the Russian Empire, with pogroms against the Jews in 1905 and again in 1920. In the Russian popular imagination, Rostov shared a certain kinship with Odessa—both multi-ethnic port towns reputed for their criminal underworlds: Odessa Mama and Rostov Papa.

Pechersky’s family was middle class and traditionally Jewish. At home, his parents spoke Yiddish. Pechersky must have learned the language as a boy but, by the time he was grown, he had forgotten what little he knew. Accounts conflict as to which of his siblings continued to speak the language—all but him, only his sisters, or just his oldest sister, Faina. She was born in 1906, a brother, Boris, nicknamed “Kotya,” was born the following year, and the youngest sister, Zina, was born in 1921. Within the family, Pechersky was known by the diminutive “Shura.” Hardly any of these details are contained in a memoir that Pechersky published in 1945—and subsequently revised—in which he devotes one short paragraph to his life before the war. The only personal detail he offers is about his love for his young daughter, Eleanora—Ella, who was born in 1934.

Ella still lives in Rostov in the three-room apartment she shared with her husband before his death in 2000. Her mind and her memory are clear but she suffers from moderate Parkinson’s and an undiagnosed condition in her legs, which has made walking difficult such that she rarely leaves her apartment. I met her on a Saturday afternoon in mid-December 2018, in the company of her daughter, Natalia Ladichenko, and Natalia’s husband, Mikhail. In the customary Russian fashion, she had taken great pains to host me and was willing to speak candidly to a stranger about her life and the life of her family.

A narrow corridor lined with bookshelves led from the entryway into a dining room with a large table in the center, a cupboard along one wall and framed photographs on the facing wall. One of the photographs was a black-and-white portrait of Ella when she was not quite 40, looking like a period cinema star. She had been a strikingly beautiful woman and, in spite of her ailments, retained the carriage and dignity of her beauty. For our meeting, she had done her hair and makeup and worn a nice skirt and blouse. Around her neck was a gold necklace with an Orthodox cross and in various places around the apartment were Russian Orthodox icons—as well as a few items of Judaica. Since her father’s passing she had become the only living person who could speak with any authority about the years of her childhood and her parents’ life in the time leading up to the war.

Her parents wed in 1933 and likely met when her father was performing some administrative function during his military service and her mother, Lyudmila, was perhaps working as a secretary in the military commissariat in Rostov. Her mother came from a Cossack family and had grown up in Tsimlya, a Cossack settlement on the banks of the Don River halfway between Rostov and Stalingrad. In keeping with Cossack tradition, she had been married off young, at the age of 15, and gave birth to a daughter, Zoya. The marriage didn’t last and Zoya remained in Tsimlya to be raised mostly by her maternal grandparents.

What brought Ella’s parents together was a mutual love of music. Lyudmila played the piano and accompanied herself on guitar. She had an exceptional singing voice, and sang not in the classic Cossack style but in the popular style of the day, the ballads and Gypsy romances performed by the likes of Klaudia Shulzhenko and Izabella Yurieva, two of the most renowned female Soviet singers of the era. In surviving photographs from that period, her parents are a striking couple. Her mother was considered a notable beauty in Rostov and her father had the dark good looks of a Rudolph Valentino.

When Ella was born, the family lived in a two-room 21-square-metercommunal apartment in a large new housing complex. To celebrate Ella’s birth, her father bought a good German piano, which he played frequently and well. Many evenings after work, her parents went to the theater, leaving Ella with a nanny. Their apartment also served as a kind of salon where her parents’ circle of artist friends would convene: Someone would sing, someone would recite verse. Her Uncle Kotya was part of this community, and the two brothers, who were extremely close, pursued these artistic interests together, played chess, and even wed on the same day. Kotya’s wife was named Nadja, also Russian, not Jewish.

Pechersky (right) with his brother Boris and sister Zinaida, Rostov-on-Don, end of the 1920sCourtesy Alexander Pechersky Foundation

For the brothers, the decision to marry outside the faith was insignificant if not laudable. They were products of the first Soviet generation, schooled in its universalism, freed from the yoke of nationality and religion. From their wives’ families, they met with no resistance. But their parents and sisters disapproved—including Zina, who was no older than 12 at the time. To appease them, the brides agreed to accept the Jewish faith, including, apparently, immersion in the mikvah.

By 1933, Rostov’s Great Choral Synagogue had been nationalized and by 1935 converted into a hospital for skin and venereal diseases, but the Soldiers’ Synagogue, built by Jewish cantonists in 1872hadn’t yet met with the totalizing judgment of the yevsektsiia, the local Jewish Section of the Communist Party. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, as elsewhere in the Soviet Union, the Rostov yevsektsiia (staffed primarily by Soviet Jews) waged a campaign against Jewish clerics—most famously Yosef-Yitzchak Schneerson, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe—and also against Zionist organizations, leading to the exile or imprisonment of their members. Some of the Zionists were Pechersky’s peers, 14 or 15 years old at the time of their convictions.

According to E.V. Movshovich’s History of the Jews on the Don, on the eve of WWII there remained only one active synagogue in Rostov-on-Don, the Tradesmen’s Synagogue. The Jewish population, which accounted for about 5% of the city’s total of 510,000, as much as doubled to some 50,000 with the arrival of refugees from parts of the western Soviet Union, making Rostov the third-largest Jewish population center in the Russian republic after only Moscow and Leningrad.

At this time, Pechersky held the title of deputy director in the maintenance and supply department (hozaistvo) at the Institute of Finance and Economics, though his actual duties consisted of overseeing the institute’s amateur music and theater programs. He was popular with the students, who would come to visit the apartment. Sometimes they toured their shows.

In April of 1941, Pechersky and his wife sent their daughter to Tsimlya to stay with her grandparents and half-sister, Zoya. They intended to join her that summer for their vacation. However, Pechersky was called up to the Red Army on June 22, the very first day of the German assault on the Soviet Union, and so never made the trip. As it happened, his wife didn’t either.

Sometime in the first weeks after his mobilization, Pechersky received a letter from home with a snapshot of Ella with Zoya and some friends in Tsimlya. He kept that photo with him, hiding it inside his tunic, throughout the entirety of the war.

By September, as the Wehrmacht steamrolled across Soviet territory virtually unimpeded, Pechersky was a quartermaster attached first to battalion headquarters and later the headquarters of the 596th Artillery Regiment of the 19th Army. They were part of the Soviet forces defending the approach to Moscow and, in October of that year, Pechersky was one of nearly 1 million Red Army soldiers caught in the German encirclement known as the Vyazma pocket. Some 250,000 soldiers fell in battle while more than 500,000 were taken prisoner.

For practical and ideological reasons, the Red Army was woefully unprepared for the German onslaught, but Soviet citizens were forbidden from acknowledging this reality. “The much-battered enemy continued his cowardly advance,” read a typically aspirational phrase in the Front newspaper. Though the experience of the encirclement must have been harrowing, Pechersky’s account of it is brief and written in the heroic-generic style of the times. At one point, he and seven other soldiers are chosen by the politruk (political instructor) of the 4th Division to help evacuate their heavily wounded regimental commissar:

Several times we attempted to lay down fire to clear the way for ourselves, but success eluded us. We ran out of ammunition. Mortar shrapnel took the lives of the commissar and one other fighter. We retreated to the forest, taking with us our dead comrades. In the evening, we buried them and laid two helmets on their graves.

Other encounters with the enemy transpired. We expended the few bullets we’d found in dugouts. And though we were tormented by hunger, these few bullets were dearer to us than bread.

Fatigued, our ammunition spent, we were caught in the enemy’s ambush and could not escape. The most terrible thing happened, which one didn’t even want to think about—we were taken prisoner.

Pechersky wrote this version of events in the 1960s, knowing what he couldn’t have known at the time: that no matter how terrible the prospect of being taken prisoner by the Germans seemed, it would prove to be far more terrible and its consequences more lasting than he could have imagined. For that reason, one understands why he wouldn’t want to linger over these events, but simply to show that he and his comrades had fought and kept fighting in the face of insurmountable odds. For three years, from the time Pechersky was taken prisoner until he rejoined the ranks of the Red Army in 1944, he had no contact with his family. He didn’t know of their fates, and for a long time they believed he was dead.

Between September and November 1941, 100,000-150,000 people were evacuated from Rostov by train and on barges along the Don. It is supposed that an additional 50,000-100,000 spontaneous evacuees fled east or south. Among the evacuees were nearly all of the Pechersky family, who ended up in different parts of the Soviet Union: Faina’s family in Tashkent; Kotya’s family in Piatigorsk; and Zina’s family, with Pechersky’s mother, also in the Caucasus. (Because of some undocumented infirmity, possibly to do with his heart, Kotya was not conscripted into the army.) The sole person to remain in Rostov during the German occupation was Lyudmila.

When he was taken prisoner in October 1941, Pechersky became one of millions of Red Army soldiers to meet this fate. In Vyazma alone, nearly 500,000 Red Army soldiers surrendered to the German forces. Ultimately, nearly 5.7 million Soviet soldiers were taken prisoner with more than half, some 3.3 million, dying by the end of the war. (By comparison, 231,000 British and American soldiers were taken prisoner with only 8,300—a little less than 4%—dying in German captivity.) Soviet POWs died of exposure, disease and starvation and were also deliberately killed. Chief among the targets for extermination were “politically and racially intolerable elements” such as commissars, intellectuals and Jews, who, per a July 1941 directive, were to be screened out among the POWs and turned over to the SS.

Pechersky, though captured in the period when such screenings and executions were taking place, wasn’t identified or betrayed as a Jew. It no doubt helped that his appearance wasn’t stereotypically Jewish. The Red Army, like the Soviet Union, was composed of many nationalities, and Pechersky could have passed for one of the other national minorities. His first and last names also were not overtly Jewish. Since he spoke no Yiddish, he didn’t have a distinctive accent. In his documents, his nationality would have been listed, but he might have lost these in the heat of battle or had the foresight to destroy or dispose of them before he was captured. Absent these, the only things that could have given him away were his patronymic, Aronovich, and the fact that he was circumcised. However he accomplished it, he was able to conceal his identity at a time when its discovery would have almost certainly spelled his death.

Somewhere from the time of his capture until the spring of 1942, Pechersky was imprisoned at a POW camp in Smolensk, southwest of Vyazma. The conditions there were abysmal. Prisoners were packed like cattle into drafty barracks where hundreds died daily from cold and hunger and were then thrown into mass graves. During this time, Pechersky contracted typhus and, in his words, “miraculously” managed to both survive and conceal his disease for seven months—as those found to be afflicted were usually shot. In May, he and four other prisoners were caught while trying to escape. Pechersky and his accomplices were sent to a penal company in Borisov, and from there to a forest camp in Minsk. One day in early August, the prisoners were forced from their barracks and made to line up two abreast for selection for work in Germany.

As is his tendency during this part of his story, Pechersky offers scant detail about this episode, even as it is where his path branched off from that of the general group of Soviet POWs and led eventually to the gates of Sobibor. One wonders how quickly he grasped the implications of this scene. Was he among the first to pass before inspection or was he obliged to watch and contemplate as others preceded him? One would like to know what went through his mind, but Pechersky writes only:

Before sending us off, they conducted a medical examination and discovered that I was a Jew.

Nine Jewish POWs, including Pechersky, were identified that day, and were taken under armed guard and interred in what was known as the “Jewish cellar.” Pechersky counted 24 steps down to this underground bunker. It was a single room packed tight with people. There was no light whatsoever. Once a day they were fed a watery soup and 100 grams of bread. When the door was opened to lower the food, the bodies of those who had died during the course of that day were removed.

By the fifth or sixth day enough men had perished that it became possible to lie down on the raw earthen floor. It was here that Pechersky met and befriended Boris Tsibulsky, a strong, coarse but goodhearted teamster, butcher, and miner from Donbass who would play an important role in the Sobibor revolt. They spent 10 days in the cellar before the survivors were released and taken to a brutal labor camp in Shirokaya (Broad) Street, near the Minsk ghetto.

On the face of it, the episode in the “Jewish cellar” fails a basic test of logic. Even Pechersky couldn’t comprehend it: If the Nazis wanted to kill them, it would have been faster and simpler just to shoot them. If they wanted their labor, why starve them and thin their ranks without deriving any benefit? Arkady Vaispapir, who spent 20 days in the “Jewish cellar” and would also end up at Sobibor, offered as explanation that the Nazis, responding to Vycheslav Molotov’s threat that the Soviets would do to German POWs what the Germans did to the Soviet, had ordered an end to the practice of routine shootings and so observed the letter if not the spirit of the law, like in a game played by nasty children.

A grim coincidence unites the time when Pechersky was put into the “Jewish cellar” and events back home in Rostov. On July 24, the Germans retook the city, which they had previously controlled for a week and then lost. In the eight months since they had last occupied Rostov, some Jews had returned, believing that it was safe. When the German forces approached again, the evacuation from the city wasn’t well organized, and there were few places to go since the German army controlled most of the surrounding area. The Jews of Rostov were effectively trapped.

By Aug. 2, orders were posted around the city requiring all Jews aged 14 and over to present themselves for registration. Included in this number were also the non-Jewish spouses of mixed marriages. The order was to be carried out by Aug. 7. Responsibility for its fulfillment fell upon the elders of the rapidly assembled Jewish administrative committee of Rostov. Synchronous with the action against the Jews, the Germans were killing Soviet POWs in the vicinity of Zmievskaya Balka (Snake Ravine), a part of the city situated between the botanical garden and the zoo. Three hundred of these POWs were forced to dig large pits in the ravine. On Aug. 8, their work completed, they were shot and buried in the pits.

That same day, new orders were directed at the Jews. On the pretext of protecting them from recent attacks perpetrated by non-Jewish inhabitants of Rostov, they were instructed to gather at 8 a.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 11, at six different assembly points for resettlement to an undisclosed location where the Germans could better protect them. They were to bring their documents and, tied to an identification tag with their names and addresses, the keys to their apartments. They were also encouraged to bring their valuables: money, as well as any items they deemed necessary to establish themselves in their new homes.

On the morning of Tuesday, Aug. 11, possibly the very day Pechersky was tossed in the hole with other Jewish POWs, the Jews of Rostov presented themselves at the collection points. They were primarily women, children, and the elderly, since most men of military age had left for the front. Some trucks were provided to take them to their destination. Other people walked in columns of 200-300 or, by some accounts, as many as 2,000. Gas vans with a capacity of 50-60 people—called dushegubki in Russian, (soul-killers)—were also employed to suffocate the victims on the way to the killing field.

The residents around Zmievskaya Balka were told to leave their homes, but some hid and later bore witness to what they heard and saw.

“To achieve the extermination of these millions of men, women and children,” wrote Gitta Sereny in her book about Sobibor and Treblinka, Into that Darkness, “the Nazis committed not only physical but spiritual murder: on those they killed, on those who did the killing, on those who knew the killing was being done, and also, to some extent, for evermore, on all of us, who were alive and thinking beings at that time.” I would add that this applies also to those of us who were not alive at that time but now possess this knowledge, especially those who would have been victims had we been alive then. The knowledge is like a disease that expresses itself when you look at your wife, your young children, your aging parents or, unpredictably, when you stand in a forest, or hear certain kinds of music.

The killings at Zmievskaya Balka were carried out by the Germans with help from Russian police auxiliaries. Jewish adults were made to strip naked before being shot. In most other mass killings, the children were treated like the adults, but it has been reported, perhaps apocryphally, that the children of Rostov were killed by means of smearing a poison on their lips. The poison was described as being yellow in color. The sources I read did not specify what this substance was or if it had a particular smell.

I have never read a description of just how this sickeningly intimate murder was performed. Were the children torn from parents who were then obliged to watch this monstrous procedure as one of their last sights on earth? Or were the children the ones who had to first see their parents, siblings and grandparents shot at the edge of a pit? Did the children resist or were they docile, resigned to their fate by terror, shock and grief? How did the killers decide who qualified as a child? The poison was described as “fast-acting,” but what did that actually mean? Were the children left to expire on the ground and later thrown into the pits or were they thrown immediately into the pits to die there among the corpses? And what does it mean to say children? Because there are no children, only one individual girl or boy followed by another and another.

The registration lists of the Jews of Rostov have never been found, and estimates of the number of Jews killed vary. The figure most historians accept is that some 27,000 people were shot in Zmievskaya Balka, of which 15,000-18,000 were Jews. The killing of the Jews of Rostov unfolded over two days. Those not killed on the first day were made to wait in place to meet their terrible ends. Some Jews reportedly committed suicide first. For days afterward, local residents continued to hear the cries of the dying.

As the spouse of a Jew, Pechersky’s wife was subject to the German order, but she was not among the victims at Zmievskaya Balka. How she avoided this fate isn’t fully known. Ella’s chronology has her mother aboard a boat around this time en route to Tsimlya. Waiting to meet her at the harbour was her elder daughter, Zoya, who was 18 years old at the time. The boat never arrived, because German planes attacked that day, sinking it and killing many of the passengers.

Ella, age 8, was playing outside her grandmother’s house when the planes appeared. She didn’t understand what they represented, even when some men nearby declared that they were not “ours.” The men scattered, and Ella’s grandmother ran out of the house, grabbed Ella and hid with her in the lee of the ravine. They emerged later to find much of the village in flames. It was a small Guernica.

Ella recalls seeing the occupants of a workers’ barracks leap to their deaths as the building burned. Her grandparents’ house was on a rise. Most everything below was destroyed. The only people to survive were those few whose houses were on the rise, and those whose houses were on the banks of the river and who managed to leap into the water. Ella’s step-grandfather was working in town and was never heard from again.

With everything around them burning, Ella and her grandmother fled. As it was late summer, the apple trees in her grandmother’s yard were heavy with fruit. Her grandmother picked some for their journey, handing an apple to Ella, who recalls being confused until her grandmother explained that the heat from the flames had baked the apples on the tree.

For the length of the German occupation, Ella and her grandmother lived in a different Cossack village, at first given a room in a house, later shunted to a pig pen or cow stall when German and Romanian troops were billeted there. Zoya, who survived the bombing at the harbor, found them some months later and moved in with them. They had no word about their mother. They also lived in fear that survivors from Tsimlya might arrive in this village and inform the Germans that Ella was the daughter of a Jew. The dire consequences of this fact were known.

For more than a year, from August of 1942 until the middle of September of 1943, Pechersky remained in the Shirokaya Street camp. The prisoners in Shirokaya were Jewish POWs, select Jewish specialists from the Minsk ghetto, and incorrigible non-Jewish Soviet POWs who had committed crimes or opposed the Nazis. At Shirokaya Street, Pechersky came to know the men whom he would later trust to carry out the most important tasks during the Sobibor uprising: the Red Army soldiers Arkadi Vaispapir, Semion Rosenfeld, and Alexander Shubayev, known as Kali Mali. Also, there was Yehuda Lerner, a young Polish Jew who landed at Shirokaya after multiple escapes from other camps. Most importantly, Pechersky became close with Shloime Leitman, a Warsaw Jew, whose wife and children had been killed in the Minsk ghetto. In Sobibor, Leitman would serve not only as Pechersky’s translator but his most trusted confidante.

Shirokaya Street was run by sadists who killed prisoners for the slightest infraction. During roll call, one guard had the habit of placing his revolver on the shoulder of the lead prisoner in a column and firing down the line, killing the first man out of step with his fellows. When two prisoners staged an escape, the SS selected every fifth man from that work group, forced them to dig a ditch, and shot them in the back of the neck. Boris Tsibulsky survived because he’d been fourth in the count. And in reprisal for a more sophisticated escape plan that involved breaking into the armory and stealing rifles and ammunition, prisoners were set upon by dogs and then tortured to death with boiling and freezing water.

“On the 18th of September, at 4 am, when it was still completely dark, all the Jews were roused from their bunks and ordered to leave the barracks with their bundles in hand,” wrote Pechersky of the morning when he and his fellow prisoners were assembled to be sent away. Among them were people drawn from the Minsk ghetto, women, children, and the elderly. Vaks, the Shirokaya Street Commandant, announced that they were going to Germany to validate their lives with honest labor. Troop trucks came and loaded the women and children. The men were formed into columns and marched toward the train station under armed SS guard. As the prisoners passed the ghetto, the emaciated ghetto residents threw food through the gaps in the barbed wire and called out: “They are taking you to your deaths!”

In a field, still some distance from the station, a line of 25 cattle cars awaited. Seventy people were pressed inside each car. The train traveled for four days, the people inside unable to sit or lie down, provided no food or water or any concession for their personal needs. Standing next to Pechersky was a young mother holding a thin, blond, 3-year-old girl. Pechersky had noticed the girl in the camp in the days leading up to the resettlement. For the duration of the trip he and his compatriots took turns holding her to give her mother some rest. What little food he had Pechersky shared with the girl—some jam, a potato, and water from his flask. She would rest her head on his chest and fall asleep, rocked to the rhythm of the train, and he was put in mind of Ella, his own daughter.

On the evening of the fifth day, the train arrived in a small outpost station. They read a sign that spelled “Sobibor,” and saw a camp ringed by three rows of barbed wire, set within a pine forest. They had never heard of the place, and didn’t suspect that the Nazis would go to the trouble of bringing them all the way to Poland to kill them, as they’d had no compunction about killing many Jews on the territory of the Soviet Union. Their row of cattle cars was switched onto a side track, and that is where they remained for the night.

At 9 o’clock on the morning of Sept. 23, a steam engine pulled their string of cars into the camp.

In the fall of 1943, Sobibor was the sole Operation Reinhard camp still functioning. Belzec had stopped receiving transports in December of 1942, and the commando of Jews tasked with burning the corpses and leveling the camp completed its work in the summer of 1943. They were then shipped to Sobibor. When they realized where they had been taken, they resisted, and a bloodbath ensued. A note found in the clothing of one of the condemned read:

We have worked one year in Belzec. We don’t know where they are transporting us. They say to Germany. In the wagons are dining tables. We have received bread for three days, canned food, and vodka. If this is a lie, you should know that death awaits you, too. Don’t trust the Germans. Take revenge for us.

On Aug. 2, 1943, the prisoners at Treblinka had risen up in a fashion not dissimilar from the one the prisoners of Sobibor would later employ. Near the end of the workday, they attacked the SS and guards, set some of the buildings on fire, and hundreds of prisoners escaped into the woods. The camp ceased its operations about two weeks later with a final transport from Bialystok.

By this time, Operation Reinhard had achieved its aims and nearly all the Jews in the General Government had been killed. In March of 1943, Himmler had given the order to shutter the camps. Auschwitz-Birkenau was fully operational and could receive Jews from all over Europe. And after the German army’s defeat at Stalingrad and the Red Army’s grinding advance toward Poland, there arose a more pressing need to hide the traces of the atrocities committed in the Reinhard camps.

The prisoners inside Sobibor did not and could not know all of these details, but they deduced that their usefulness was waning and that the Nazis would not hesitate to eliminate them. The fiendish irony was that their survival depended on a steady supply of other Jews for the Nazis to murder. Richard Glazar, who survived Treblinka, recalled his and his fellow prisoners’ reaction when they were informed in the spring of 1943 that new transports would be arriving after a significant lull. “Do you know what we did? We shouted, ‘Hurrah, hurrah.’ It seems impossible now. Every time I think of it I die a small death; but it’s the truth.”

There were two different protocols at the Operation Reinhard camps for the arriving transports: deception and terror. Jews from Western Europe—Holland, Czechoslovakia, France, Austria, and Germany—usually arrived in coaches, and the passengers were greeted in a courteous manner. The Jews of the Bahnhofkommando (platform workers) would help the passengers from the carriages and provide them with claim tickets for their luggage. Eastern European Jews arrived in cattle cars and were met with shouts, beatings, and brutality from the moment the cattle car doors opened. The reason for this was that Eastern and Western European Jews were regarded as coming from different worlds—one impoverished and backward, the other wealthy and civilized—a bias often shared by the Jews themselves.

As a transport from the east, Pechersky and his group would have been greeted with a display of brutality. However, whereas few if any people were selected from an arriving transport and everyone else driven swiftly through a set of predetermined stations, this time the SS asked for “carpenters and joiners without families” to step forward. Some 80 men did, including Pechersky and some of the prisoners from Shirokaya Street. They were taken to a neighboring section of the camp, which was separated from the unloading platform by a barbed wire fence. Everyone else from the transport was marched through a set of gates and disappeared from view.

It is important to note that accounts of what happened over the next several weeks are not uniform and sometimes conflict. Those who survived recall events differently and, over time, people’s recollections have either wavered or calcified into a certainty. To read or listen to the different accounts is to encounter a range of contradictions, small and large. For instance, it remains unverified why the Nazis needed these 80 men and why they would have admitted scores of Red Army soldiers into the camp.

Like the other Operation Reinhard camps, Sobibor was organized into three sections: Camp I, where transports were received and where the various workshops and prisoner barracks were located; Camp II, the undressing yard for the condemned, the barracks where the women’s hair was cut, the Lazarett where weak or disabled Jews were taken to be shot, and all the warehouses and sorting rooms for the belongings of the murdered; Camp III—connected to Camp II by “the tube” or the Himmelfahrtstrasse (the Road to Heaven) a narrow path some 250 meters in length—housed the gas chambers, the burial pits, the “roasts” for burning the bodies, and the barracks for the Jewish prisoners employed there. At the time of Pechersky’s arrival, the Nazis were also constructing Camp IV for storing and repairing captured Soviet munitions, and the Jewish POWs were assigned to do the hard physical labor of clearing the forest and building the barracks.

One possible reason why such an unusually large number of men was chosen from Pechersky’s transport was because the Nazis had recently foiled an escape plot attributed to 72 Dutch prisoners. All the Dutchmen were killed, and their places on the work crew needed to be filled. However, this same reason—the foiled plot by Dutch prisoners—was offered by Thomas Blatt for why he was selected when his transport arrived in April of 1943.

After Pechersky and his comrades were separated from the rest of the transport, they were taken to a barracks where, after such a long and arduous trip, many men climbed onto the bunks and fell asleep. Pechersky and some others, including Shloime Leitman, elected to go outside. It was a warm autumn day and they spread themselves out on some logs. They were soon approached by a Sobibor prisoner, a man in his early 30s.

Why the prisoner gravitated specifically to Pechersky is unclear. One account claims that it was discernible from Pechersky’s uniform that he was an officer and that the other soldiers deferred to him—though it is doubtful that after two years in POW camps Pechersky’s uniform would have borne any marks to identify him as an officer. It may simply have been that Pechersky had an impressive physical presence and a personal charisma. At 34, he was also about a decade older than most of the other POWs and so wielded the authority of age and experience.

The man who approached Pechersky was Leon Feldhendler a Polish Jew who had been in Sobibor for nearly a year and who led the camp’s underground organization. In Pechersky and the Soviet POWs, he saw potential allies who could provide what the underground lacked, a cadre of men with military experience. Speaking in Yiddish, with Leitman translating, Feldhendler told them the truth about Sobibor. Indicating the black smoke that rose in a far corner of the camp, Feldhendler said: “Those are the bodies of the people who were with you on the train.”

That night, as Pechersky tried to come to terms with the knowledge of what confronted all new arrivals, he was tormented by thoughts of the little girl from the train.

A kind of mythology has attached itself to Pechersky’s time in Sobibor, founded on a number of extraordinary scenes and exchanges. Few of the people who witnessed them lived to see the end of the war, but Pechersky was consistent in recounting them and, as all who knew him affirmed, he was not a man to aggrandize himself.

I. The story of the marching song:

On their first workday in Sobibor, Pechersky and the Soviet POWs are ordered by SS Sergeant Frenzel, who was in charge of Camp I, to sing a Russian song as they march to work. Provocatively if not recklessly, Pechersky instructs his men to sing the martial hymn “If Tomorrow War Comes.”

If tomorrow war comes

If the cruel foe attacks

If the dark force descends down upon us.

Then all like one man

All the Soviet folk

Will rise up in defence of our homeland.

This way, in formation, singing in full voice for the whole camp to hear, they set off.

II. The story of the stump:

Two days later, Pechersky is among 40 prisoners chosen to chop logs and remove stumps from Camp IV. Working beside him is a strapping, bespectacled, Dutch youth. Or merely a tall thin one. The scene plays out variously in different tellings. The youth is weak and barely manages to lift his axe. Or he stops momentarily to wipe his glasses and is immediately struck by the whip of Sgt. Frenzel, who was posted that morning to Camp IV. The young man’s glasses fall and break so he can no longer see. He tries to carry on as Frenzel repeatedly whips him. Pechersky, standing nearby, is disgusted by the sight and momentarily rests his axe, drawing Frenzel’s ire. Frenzel commands him to approach. By some means—either in broken Russian (unlikely), or in as much German as Pechersky could comprehend (more likely), or with a kapo named Pożycki acting as translator (most likely)—Frenzel communicates to Pechersky that he will give him five minutes to split a large stump. If he succeeds, Frenzel will reward him with a pack of cigarettes; if he fails, 25 lashes. The Nazi consults his wristwatch and orders Pechersky to begin.

The stump is large, hard, and full of knots; Pechersky lays into it with all his might. His hands and back ache. But he manages to split the stump with 30 seconds to spare. Keeping his promise, Frenzel extends a pack of cigarettes.

“Thank you, but I don’t smoke,” Pechersky declines.

Expecting a beating, Pechersky nevertheless returns to his place in the work gang and resumes chopping. Frenzel walks off and returns some minutes later with half a loaf of bread and a lump of margarine.

“Russian soldier, take,” Frenzel commands.

Despite his hunger, Pechersky knows the bread has been taken from Jews whom the Nazis have killed, and before his eyes it appears as if the bread is soaked in their blood.

“Thank you,” Pechersky says, “but the rations I receive here satisfy me.”

Frenzel storms off, leaving the gang under the supervision of Kapo Porzyczki. By evening word of the encounter has spread throughout the camp.

III. The story of the crying child:

The very next day, Pechersky and his comrades are again sent to work in Camp IV. A new transport has arrived and the distance between the gas chambers and the site of Pechersky’s work party is not very great. A barbed wire fence woven with pine branches separates them, making it impossible to see what is happening on the other side. At first there is silence but it is shattered by the cries and screams of women and children. Pechersky hears distinctly the voice of a small child calling out for its mother. The voices are then drowned out by the maniacal honking of hundreds of geese, which the Nazis keep for this purpose and to supply their tables. Pechersky feels himself paralyzed with horror and helplessness. Leitman and Tsibulsky are beside him, deeply shaken by what they’ve heard.

“We must get away from here,” Tsibulsky says. “The forest is only two hundred meters. The Nazis are distracted. We can cut through the wire and kill the guards with our axes.”

“We might succeed,” responds Pechersky, “but the Nazis will slaughter the others in reprisal. If we go, all must go. Some will survive to tell the tale.”

“You’re right,” agrees Tsibulsky. “But we mustn’t delay. Winter is coming and the snow will show our tracks.”

A mere three weeks elapsed from Pechersky’s arrival until the uprising. In that span Pechersky was able to establish trust in a fraught, stratified, and dangerous environment and formulate and implement an ambitious and intricately choreographed plan. On his seventh day in the camp, he accepted Leon Feldhendler’s invitation, and both he and Shloime Leitman joined the camp’s underground committee, which consisted of the heads of the various workshops—shoemaking, tailoring, metalworking and carpentry. Because the heads of the workshops had some latitude about whom they wished to employ, by Oct. 8 both Pechersky and Leitman were installed in the carpentry workshop for their protection.

The planning for the revolt was done in nighttime meetings at the carpentry workshop and in the evenings in the women’s barracks where prisoners were permitted to socialize. At Feldhendler’s suggestion, Pechersky found himself a “girlfriend” to serve as cover so he and Feldhendler could meet without attracting too much attention. An 18-year-old girl who went by the name Luka agreed to the arrangement. Because she spoke neither Russian nor Yiddish, Pechersky, Feldhendler and Leitman could speak in front of her without her understanding. Over time, a genuine affection developed between Pechersky and Luka, and they took to meeting on their own, though Pechersky always insisted that relations between them were chaste. In his memoirs Pechersky offers long and lucid dialogues between them, even as the language barrier would have made that impossible. But by some means they communicated, presumably because Pechersky would have picked up some German during his time in the POW camps or there is the possibility that he had studied the language in school.

Luka was from Hamburg; her father was a communist. After the Nazis assumed power, they hunted her father and tortured Luka to make her reveal his whereabouts. She was only 8 at the time, but she kept his secret, and her father subsequently fled to Holland. The family followed and lived in peace until the Nazis invaded. Her father fled farther east but Luka, her mother, and two brothers were rounded up and sent to Sobibor. Her brothers were killed while she and her mother were selected for work.

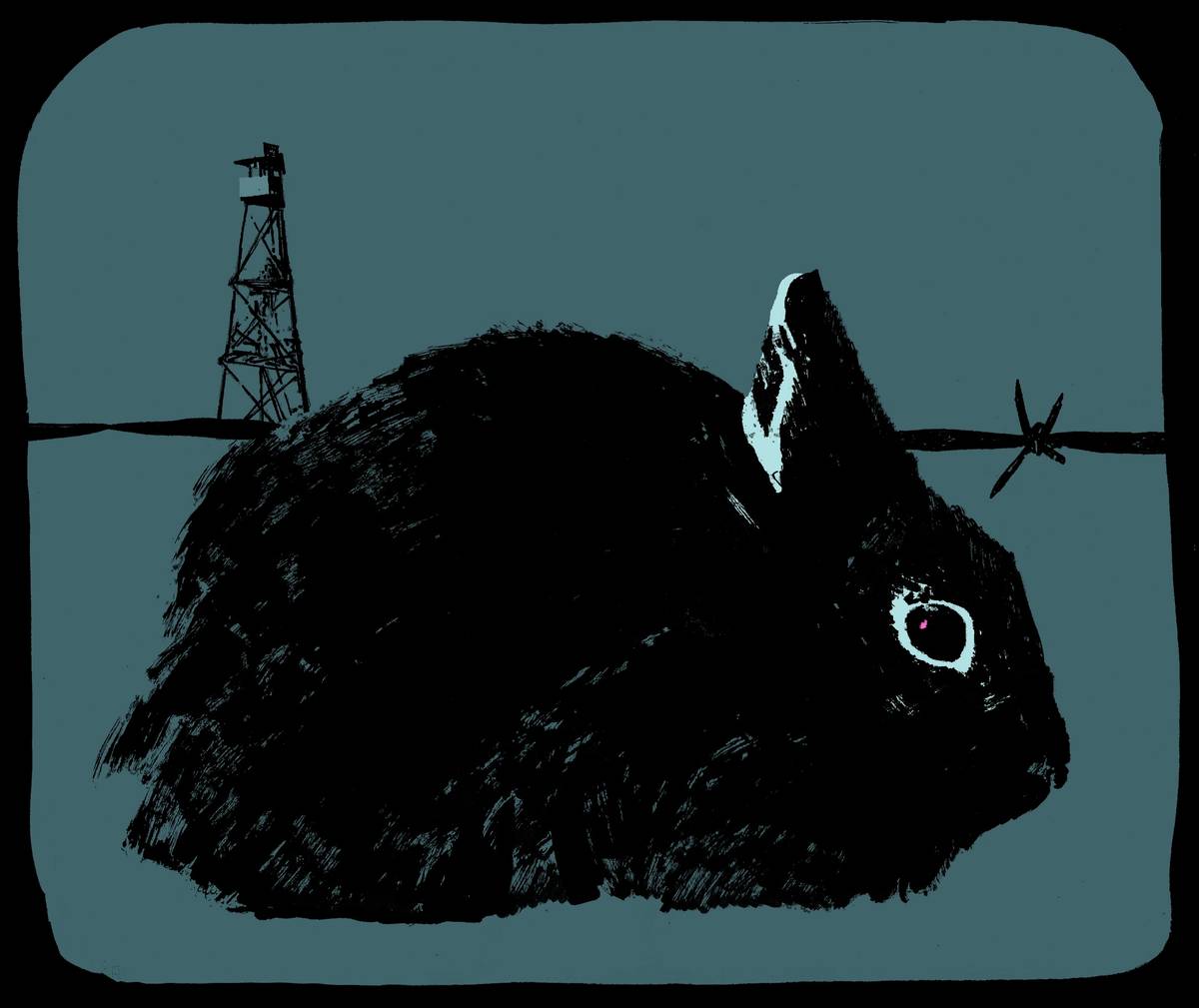

Luka’s job was to tend the rabbits the Nazis raised for slaughter, their hutches in close proximity to Camp III such that she could hear and even glimpse what went on there through gaps in the pine branches. One imagines her with the dumb innocent rabbits, the sounds of horror in the background, representing their shared fate.

Pechersky, Leitman, and Feldhendler contemplated two different plans: digging a tunnel from the camp to the forest or luring SS officers to the workshops and killing them. Pechersky dismissed the idea of the tunnel because it seemed improbable that several hundred prisoners could crawl through a narrow tunnel in a calm and orderly fashion over the course of one night.

The idea of luring and killing the SS officers, while more treacherous, looked to stand a better chance of success. There were only about 20 SS officers at the camp at any one time. If most of them could be eliminated, the auxiliary guards—drawn primarily from Ukrainian Soviet POWs, numbering from 100-200, and not necessarily loyal to the Germans—would be left to their own devices and might not stop the prisoners from fleeing. And if the killings were undertaken near the end of the workday, the prisoners might be able to melt into the forest as darkness fell, making pursuit unlikely until morning.

Pechersky’s terms for the revolt were that he would personally select the assassins from the ranks of the men who had come with him from Minsk, and that the final word would be his. On Oct. 7, over a game of chess, Pechersky and Feldhendler agreed to this plan.

Pechersky projected confidence but he was skeptical that the plan would work. At best, he thought they would be able to kill some of the SS and a few prisoners might make it to the woods. But he shared these doubts only with Shloime Leitman.

In the week leading up to the revolt, the main challenges were keeping the plan secret—they agreed that no one but the members of the committee would know of it until the appointed day—and establishing exactly how much ammunition the Nazis entrusted to the guards on duty. The answer was five rounds.

On the morning of the 14th, Pechersky called in each of the men he’d designated to serve as assassins and gave them their orders. Organized into teams of two, and equipped with short whetted axes, the assassins took to their posts at around 3 p.m., an hour before their targets were to arrive. Some of the men were informed of their targets, some were not. Military discipline was observed, and nobody questioned Pechersky’s orders. On the contrary, recalling the day in an interview with Claude Lanzmann, Yehuda Lerner, only 17 years old at the time and having never killed before, regarded the assignment as “a big honor” and went “willingly and with a light heart.”

In many ways, Pechersky and the plotters were lucky. By happenstance, Franz Reichleitner, the commandant of Sobibor, and Gustav Wagner, probably the most vicious and savvy of all the SS men, were on leave at the time. “Nearly all of us state with certainty,” recalled survivor Moshe Bahir, “that if [Wagner] had stayed in the camp until the end, the revolt would not have broken out, or would have failed from the outset.”

The plan was largely predicated on the Nazis’ covetousness and greed; their renowned Teutonic punctuality; and their conviction that the Jews posed no threat. To effect the plan, young boys, called putzers, who did small jobs for the Nazis and had considerable freedom to roam the camp, were enlisted to entice the SS to visit the workshops at appointed times. Waiting for them amidst the actual tradesmen were the assassins. Until the killing started, the tradesmen didn’t know what was afoot.

The first two kills were committed by Shubaev in the tailor shop. Afterward, he reported to Pechersky and presented him with one of the Nazis’ revolvers. Tsibulsky was sent to the sorting sheds of Camp II and killed four SS men. Yehuda Lerner and Arkady Vaispapir, the only team of assassins to both survive the war, killed two SS in the tailor shop.

The first man to visit the workshop was Siegfried Graetschus, commander of the Sobibor “Ukrainian” guards. In Vaispapir’s telling, he snuck up behind him and struck the first blow; in Lerner’s telling, he did it. Either way, Graetschus was killed. Moments after the workers cleaned up the blood and concealed Graetschus’ body, another Nazi entered—either by chance or by appointment. Looking about, he spied a hand poking out from under a pile of coats. When he went to investigate, Vaispapir and Lerner pounced.

Shloime Leitman lured an SS man into a barrack under the pretense of needing his direction for the work being done inside and killed him with his axe.

Aside from his role as commander over the uprising as a whole, Pechersky also assigned for himself and Semion Rosenfeld the task of killing Karl Frenzel. Frenzel was expected to come to the carpentry workshop to see about some cupboards, but he never did. “I prepared myself thoroughly for this task,” Rosenfeld recounted years later. “But the scoundrel did not come. Until today I am sorry for that.”

As time ticked down and with no sign of Frenzel, Pechersky sent for Luka. They met in the carpentry workshop and he informed her about the revolt and instructed her to go to her barracks and change into men’s clothing, as these would be better suited for running and surviving in the woods. Luka left and returned not long after bearing a shirt she insisted Pechersky put on. It was her father’s shirt and she assured him that it would protect him and bring him luck. Pechersky, not inclined toward superstition, at first demurred but ultimately relented. Before Luka ran off to alert her mother, Pechersky told her that when she heard the bugle sound for roll call, to find him and be by his side.

It was known that much of the perimeter around the camp was mined—to keep prisoners in and partisans out. Pechersky had hoped that once most of the SS had been eliminated, the prisoners might be able to be led out the front gates, where there were no mines. But things didn’t go according to plan. Some prisoners spontaneously killed an SS man in the garage. Then SS officerErichBauerreturnedunexpectedlyandorderedtwoJewishboystounloadatruck, whereupona guard discovered the dead bodyandBaueropened fire.

Pechersky ordered the bugle to be blown ahead of schedule. When the prisoners assembled, they sensed something was astir and became unruly. Shots rang out, and the remaining SS then opened fire. Prisoners who had secured arms fired back. Any semblance of order dissolved and people ran for the fences and tried by any means to get through the wire as the guards in the watchtowers unloaded with their machine guns.

Pechersky made his way to the part of the camp that housed the SS officers because he rightly surmised that the area around there would not be mined. At one point, he spotted Karl Frenzel shooting at prisoners with a submachine gun. Pechersky took aim with his revolver and fired two shots, but none found its target. He then ran for the woods.

Unlike in Treblinka, where the underground organization found a means to communicate with the Sondercommando in Camp III and include them in the uprising, no such contact was possible in Sobibor. All those prisoners, who’d been forced to dispose of the corpses of the murdered, remained at the camp and were killed. Among the prisoners who made it to the woods, a significant number were Soviet POWs, including some of Pechersky’s most trusted comrades—Boris Tsibulsky, Alexander “Kali Mali” Shubaev, and Arakady Vaispapir.

Pechersky did not see Feldhendler, but others reported to him that he had survived the escape and was headed with a group of Polish Jews in the direction of Chelm, a nearby town. But Pechersky also received the devastating news that Shloime Leitman had been wounded during the revolt and, though he made it as far as the forest, was so badly injured that he asked his comrades to shoot him. They said they would try to take him to the partisans, but Pechersky never heard from him again. To this day, Luka’s fate remains unknown.

There was no time to dwell on any of this, as the escapees needed to get as far away from the camp as they could before day broke. As part of the plan, a Jewish electrician had cut the telephone line and sabotaged the electrical generator to hinder the Germans’ ability to communicate. Not until 8 p.m. was Frenzel able to call for help; reinforcements didn’t reach Sobibor until later that night. But by morning 400-500 soldiers, police officers and SS were actively engaged in pursuing the fleeing prisoners. They blocked the crossings of the Bug river east of Sobibor, which, in many places, represented the border between Poland and Belarus. Luftwaffe planes were also assigned to the manhunt. Within the first few days of this pursuit, it is estimated that 100 of the 300 prisoners who made it to the forest were captured and subsequently killed. For the Nazis, it was important to capture and kill all the escaped Jews not only to fulfill their genocidal mission but also to preserve its secrecy.

Pechersky’s objective was to cross the Bug and link up with Soviet partisans. On the first day after the revolt, he found himself leading a group of some 60 people, a mix of his Red Army POWs and Jewish prisoners from different countries. But it was clear to him, as it was to some others, that it would be difficult if not impossible for such a large group to avoid detection. Further, the Polish Jews knew the language and the territory and could fend for themselves, whereas he and his men were Red Army soldiers who wished to return to their country and resume the fight against the fascists.

On Oct. 16, Pechersky writes that with everyone’s consent he and his Soviet POWs split off from the others and headed east toward the Bug. The Polish prisoners remembered it differently. And as much as they revered him and knew that they owed their lives to him, bitterness lingered over the way he left. Shlomo Alster, a Polish Jew who had been in this group, recalled it this way:

Sasha’s people left us and went away. We remained without a leader. What could we do? Without arms and without a man to lead us. Together with us were French, Dutch, and Czechoslovakian Jews. They could not find their way without knowing the language and the surroundings. Like us, they also divided themselves into small groups. They went out to the road, which was full of SS men, and all of them were caught alive. Also the local people caught them one by one and brought them to Sobibor, where they were liquidated.

The subject of the local people’s attitude toward the Sobibor escapees is a painful one. Many Polish partisan units wouldn’t accept Jews, and some, including detachmentsof the Armia Krajowa (The Home Army), actively killed them. There is also the ghoulish fact that local people dug up the earth where the Operation Reinhard camps had stood and picked through the ash and bones in search of Jewish gold. To stop this, the Nazis established small farms on the territories of each of the camps and settled a Ukrainian guard and his family there.

Pechersky, 1944-1945Courtesy Alexander Pechersky Foundation

“On the whole, with some exceptions,’ writes Yitzhak Arad, “the local population did not aid the escapees. Anti-Semitism, greediness, the fear of German terror and punishment were all contributing factors. Yet it should also be noted that those who did succeed in remaining alive until the liberation were in part saved by the aid extended to them by the local population at critical junctures after their escapes from the camps.”

One of those who was aided was Pechersky. On the night of Oct. 19, he and the Soviet POWs found a place to cross the Bug that was pointed out to them by locals. Two days later, Tsibulsky became very ill with pneumonia and the others were forced to leave him in a villager’s hut.

On Oct. 22 a week after the revolt, in the region of Brest, Pechersky and his men encountered a group of Soviet partisans. Some of Pechersky’s comrades were taken into this group while others, including Pechersky, were accepted into a different one.

“Of my existence and actions among the partisans is a separate chapter, which I might return to someday,” Pechersky wrote, but he never did. He also never wrote about what happened to him after the front caught up to his partisan unit except to say that he rejoined the Red Army, fought, was wounded in August of 1944, and spent four months in hospital before returning home to Rostov. These omissions are not surprising, given the stigmatized status of POWs in the Soviet Union after the war.

But to close out the chapter that marked him for life, it should be said that Pechersky was exceptionally fortunate. By the harsh calculus of the times, he should not have survived. Of the 450,000-600,000 Jews brought to Belzec, only two are confirmed to have survived; of the nearly 850,000-880,000 brought to Treblinka, about 50 survived; of the 170,000 Jews brought to Sobibor 57 survived. For Pechersky to have cumulatively survived all of the perils of war, followed by his years in penal camps, then at Sobibor and his escape, then a year as a partisan and then service in a very dangerous battalion in the Red Army is extraordinary. To be a Soviet citizen, let alone a Soviet Jew, and to have lost not a single close relative during the war is also exceedingly rare. The losses Pechersky did sustain were of the people who were dearest to him during the war, and whom he mourned for the rest of his life: Shloime Leitman, Boris Tsibulsky, Luka, and Alexander “Kali Mali” Shubayev, who is presumed to have been killed while fighting with the partisans.

In 2006, on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the massacre in Kyiv’s Babi Yar, Leonid Terushkin, an archivist at the Russian Holocaust Center, attended the memorial ceremony. While in Kyiv, Terushkin made contact with Arkady Vaispapir, who lived in the city. In 2008, based on his interactions with Vaispapir, another surviving Soviet POW, Aleksei Vaitsen, and the material available to him at the time, Terushkin and two co-authors, Semyon Vilensky and Gregory Gorbovitzky, published the first scholarly book on Sobibor in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Around this time, the lawyer and Holocaust expert Lev Simkin came across the Soviet trial records of 12 Sobibor guards, including lengthy transcripts of the testimony of Alexander Pechersky. His book on Pechersky appeared in Russia in 2013 and was reissued in 2019. More recently, another exploration of Pechersky’s life was written in English by the Dutch historian Selma Leydesdorff, whose paternal grandparents were killed in Sobibor.

But the most consequential event for the revival of Pechersky’s memory took place in 2011, when a man named Ilya Vasiliev attended a poetry reading in a literary café in St. Petersburg. Vasiliev was 40 years old at the time, a political scientist by training, well-connected in both Israel and Russia, and engaged in promoting memorial projects about two Soviet Jews—Shmarya Yehuda Leib Medalia, a rabbi, and Meer Akselrod, a painter. The poem being recited was called “Luka,” inspired by a small exhibit the poet, Mark Geylickman, had stumbled upon at a Moscow synagogue.

Prior to that evening, Vasiliev knew virtually nothing of Pechersky and Sobibor but be was intrigued by what he heard. The poet introduced him to the woman who had organized the exhibit at the synagogue. She in turn introduced him to two friends of Pechersky’s who lived in Israel and who tasked him with raising Pechersky’s profile to the level of a global hero, on par with Raoul Wallenberg.

Vasiliev would go on to author a book from which the screenplay for Sobibor was adapted, and he was also a producer on the film. I met him in late December 2018 at Mosfilm, the iconic Moscow film studio, where the producers of Sobibor had their offices. The day before he had been in Rome, where he’d flown with Khabensky to attend an audience with Pope Francis and present the Holy Father with a DVD of the film.

Vasiliev is tall and sturdily built, with a shaved head and eyeglasses. He is self-assured, quick to disparage the flaws of his adversaries, but also open to debate, capable of irony, and transparent about what he is trying to accomplish. Though he has a solid grasp of Pechersky’s biographical details, he doesn’t consider himself a historian. His talent is for encapsulating the essence of an idea and framing it in a way that is comprehensible and practicable. His worldview also inclines toward the conservative, which makes him well-suited to operating within the current Russian and Israeli political systems.

As this pertains to Pechersky, he grasped very early a few basic concepts. The first was that in order to propagate anything on a mass scale in Russia one needed the support of the government. Those who had written about Pechersky before had anti-Putin political leanings and criticized the Russian regime for neglecting Pechersky, thus guaranteeing that their efforts would never reach a mass audience. The other thing Vasiliev realized was that Pechersky’s story aligned perfectly with the Soviet/Russian narrative of WWII: weak, helpless Western European countries who surrendered to Hitler had to be rescued by the Red Army. The same thing occurred in Sobibor, where defenseless, impotent citizens of Western European countries needed Soviet citizens to arrive, quickly take stock of the situation and triumph. (If one ignores a fistful of quibbles, this account is basically correct.)

This patriotic Russian narrative functioned as a sword and a shield for Russia against European countries who found it now suited them to draw an equivalency between Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union. This equivalency didn’t wash in Russia and, for obvious reasons, it didn’t wash in Israel either. In this way, the Sobibor and Pechersky story offered a useful tool for Russia and Israel against revisionist foes and created a politically useful bridge between them. When Netanyahu visited Moscow in 2018, he and Putin toured the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center specifically to view an exhibit about Sobibor and Pechersky and make statements of mutual purpose.

Vasiliev’s strategy for enshrining Pechersky’s memory rested on three pillars. One was to gain official recognition for Pechersky in various countries in the form of awards, street names, monuments, and other tangible manifestations of honor: Both a train and an airplane now bear his name, as well as several streets in Russia and in other countries whose citizens were murdered at Sobibor. In 2016, Pechersky’s granddaughter traveled to the Kremlin to receive a posthumous award for bravery directly from Vladimir Putin.

The second pillar was to seek out and collect all the documents related to Pechersky and establish a definitive archive. And the last was to produce, or encourage others to produce, books and films about Pechersky so that his story would reach the widest possible audience. With the assistance of backers in Israel, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Poland, and America, Vasiliev created a foundation, The Alexander Pechersky Fund, to administer these activities in different countries. When we spoke, the fund was a modest enterprise with a rudimentary website and three employees, Vasiliev being one of them, albeit unpaid.

Until he and his comrades crossed the Bug river, Pechersky’s life had been essentially unhampered by politics. Before the war, he’d been a loyal Soviet citizen, absent any counterrevolutionary tendencies. He hadn’t fallen victim to the repressions that devastated others at that time—not as a religious Jew, or a Zionist, or a kulak, or a communist of the wrong deviation who had fallen afoul of, or was arbitrarily swept up by, Stalinist paranoia. At the front, in the POW camps, and in Sobibor he’d been treated the same as everyone else.

But once he crossed the Bug into Belarus he acquired the status and stain of a Soviet POW. Pechersky and POWs like him were looked down upon and treated poorly because they served as a shameful living reminder of the fecklessness of the Red Army’s—and by extension Stalin’s—response to the German assault in the first stages of the war. Those who died in captivity were easy to disregard, but those who survived were treated as unreliable, or worse. So it’s safe to assume that when Pechersky and his comrades first encountered Soviet partisans they weren’t necessarily welcomed with open arms: An account exists, in fact, that the first partisans they met stripped them of their weapons and cast them aside.

Once Pechersky and his Jewish POWs were accepted into the partisan ranks, they were divided up among different units. Pechersky served as a saboteur, attacking rail lines. In late April of 1944, the front reached them and his outfit was absorbed into the Red Army. However, as a former POW, Pechersky was assigned to a reserve regiment for about two months, before being sent to an NKVD filtering camp where POWs were screened to establish how they’d survived in occupied territory. Pechersky held the rank of lieutenant, as the army had automatically promoted all quartermasters to officer class not long into the war.

Though in nearly all the accounts of his wartime service Pechersky is described in terms that create the impression that he was a seasoned combat officer, this was far from the truth. (One might suppose that his ability to organize and lead the uprising in spite of his negligible military training would make his accomplishment seem more rather than less impressive). As an officer, Pechersky fell under even greater suspicion, since it was known that the Nazis treated officers more harshly, routinely executing them. Rather than being decorated for his heroism in Sobibor, he was assigned to a shturmbat, a storm battalion, a formation consisting of officers such as himself deployed in the most dangerous missions. This phase of Pechersky’s war record is also often misrepresented, with Pechersky said to have served instead in a shtrafbat, a penal battalion made up of inmates from the gulag and soldiers who had committed crimes while in uniform. In practice, these two battalions were very similar, their members known as smertniki, the walking dead, condemned to “cleanse their guilt with their blood.”

Legend has it that, before he was sent to the front, Pechersky was permitted to travel to Moscow to give testimony about Sobibor to the Jewish Antifascist Committee. The committee included the writers Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman, who were leading the effort to collect documents and testimony for a compendium called The Black Book about what we now call the Holocaust. In my English edition of The Black Book, Sobibor is spelled Sobibur and is identified as “the button factory” for the fraudulent claim the Nazis apparently circulated to placate the Jews being sent there. (I have not come across this detail in any other source.) Pechersky is mentioned but, for some reason, incorrectly identified as “the political instructor Sasha, of Rostov.” There are also some flaws in the description of the killing process. However, the only people who could have corroborated it were the SS and the Ukrainian guards, but nobody would hear from them until the criminal trials of the 1960s and ’70s.

Pechersky’s military and hospital records indicate that his battalion participated in Operation Bagration, a massive and highly successful Soviet push to recapture large swaths of Belarus, Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia. On Aug. 20, 1944, Pechersky was in combat in the area of Bauska, Latvia, and was seriously wounded by mortar shrapnel to his right thigh. He was hospitalized for four months, and after more than three years as a soldier, POW, death camp inmate and partisan, his war was over.

Since the other Jewish POWs he was with weren’t officers, they were taken into the ordinary ranks of the Red Army, where they also fought with distinction. Semion Rosenfeld went as far as Berlin, where he carved the words, Baranovici, Sobibor, Berlin into the walls of the Reichstag.

Rostov was liberated by the Red Army for the second time on Feb. 14, 1943. After the ice broke up on the Don, Ella and Zoya boarded an old barge with many others and sailed south. The trip took several days. For food, men caught fish; for water, they drank from the Don.

Ella was a child of 9 when the two sisters returned to Rostov. They made their way to her old apartment and found that it was still standing and that their mother was alive. One can imagine this scene of intense gratitude and affection, which was repeated millions of times across the country, except when it was not.

As joyous as it must have been to discover her mother alive, Ella would have also learned that her father had fallen at the front. A funerary notice was sent by the army in late 1941 or early 1942, around the time Pechersky was caught in the encirclement, informing the family that he’d died a hero’s death. Not until letters arrived from Pechersky in 1944 did they receive any information to the contrary. By that time, the rest of Pechersky’s family was resettled in Rostov.