The summer after my sophomore year in college, I returned to my hometown of Palo Alto to work as an intern in the sports department at the Peninsula Times Tribune. The PTT was one of several thousand suburban newspapers in existence at that time, perhaps the worst. This would explain why they agreed to let me work for them, though another factor would have been my salary: $60 per week.

I was 20 years old, the proud owner of an exceptionally dull childhood and a brand-new used Mercury Bobcat. Everything was thrilling. Proofreading the box scores? Wowzer! Writing up my own profile for the company newsletter? Awesome! Listening to the sports editor berate me for fetching him decaf (“I’m what now, a faggot?”) An honor!

About a month into my stint, the pop music critic fell ill. I knew this only because one afternoon I spotted the features editor whispering to the city editor, who then shouted to the entire newsroom, “Anybody know anything about Bob Dylan?”

Afternoons were the dead zone at the PTT. There was nobody around, aside from us sports goons and the mushrooms on the copy desk—populations deeply, almost tenderly committed to the avoidance of discretionary labor.

“Bob Dylan!” the city editor bellowed. “We need someone to review Bob Dylan. We need someone to go and review Bob goddamn Dylan!”

After a minute or so, I marched over to the city editor and said, with what I’m sure I considered self-possession, “I can do it.”

“I give up,” he said. “Who the fuck are you?”

“Almond,” I said. “The new guy in sports.”

“Why’reya always standing around?”

“I don’t have a desk,” I said. “I’m the intern.”

The city editor closed his eyes and pressed the heels of his palms into the sockets. This did not strike me as a good sign.

“You know anything about Dylan?” he said, finally.

“Know about him? He’s only my favorite singer in the world.”

Was Bob Dylan my favorite singer on earth?

Technically, no. I had heard of Dylan of course. My parents were late-model hippies, after all. But I’d never really heard his music. This seems absurd to me now, but back then I was not such a music freak. I was a lonely sports intern who had worshipped Styx through high school and whose appreciation of 60s music extended no further than the Beatles. So it was off to the public library, which is where people went to find out about things before God invented the Internet.

I asked the woman at reference if she had any records by this Bob Dylan character. She pointed to a shelf that ran the entire length of the wall. Holy shit, I thought. I checked out the maximum number of LPs (six) and raced home to read the liner notes and memorize the songs.

It was clear to me—based on the volume of his output alone—that Dylan was a rather large cheese in the music biz. And his melodies were often quite lovely. But my first impression of his music—one that will be familiar to other ingrate schmucks who come to Dylan late—was this: What, the guy can’t afford a decongestant?

The show was at the Shoreline Amphitheater, a lovely outdoor venue built atop a landfill in Mountain View. I had two tickets, but no one to go with. So I gave it away instead, to a pretty girl I hoped might sit next to me. Dylan was traveling with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers back then. He was in the midst of the longest slump of his long career, having just released Knocked Out Loaded to general indifference. The Reagan era had boiled him down to mush. In a year or so, he would join the Traveling Wilburys, a supergroup whose ultimate musical significance can be summed up with these two words: Trivial Pursuit.

I didn’t know any of this back then, though. He was just this legendary sinus sufferer I had to review. I found a seat on the grass and scribbled notes as he played and begged the folks next to me for the titles. Did I enjoy the show? Not especially. I was too caught up in the need to write the review, which I imagined would launch my brilliant career.

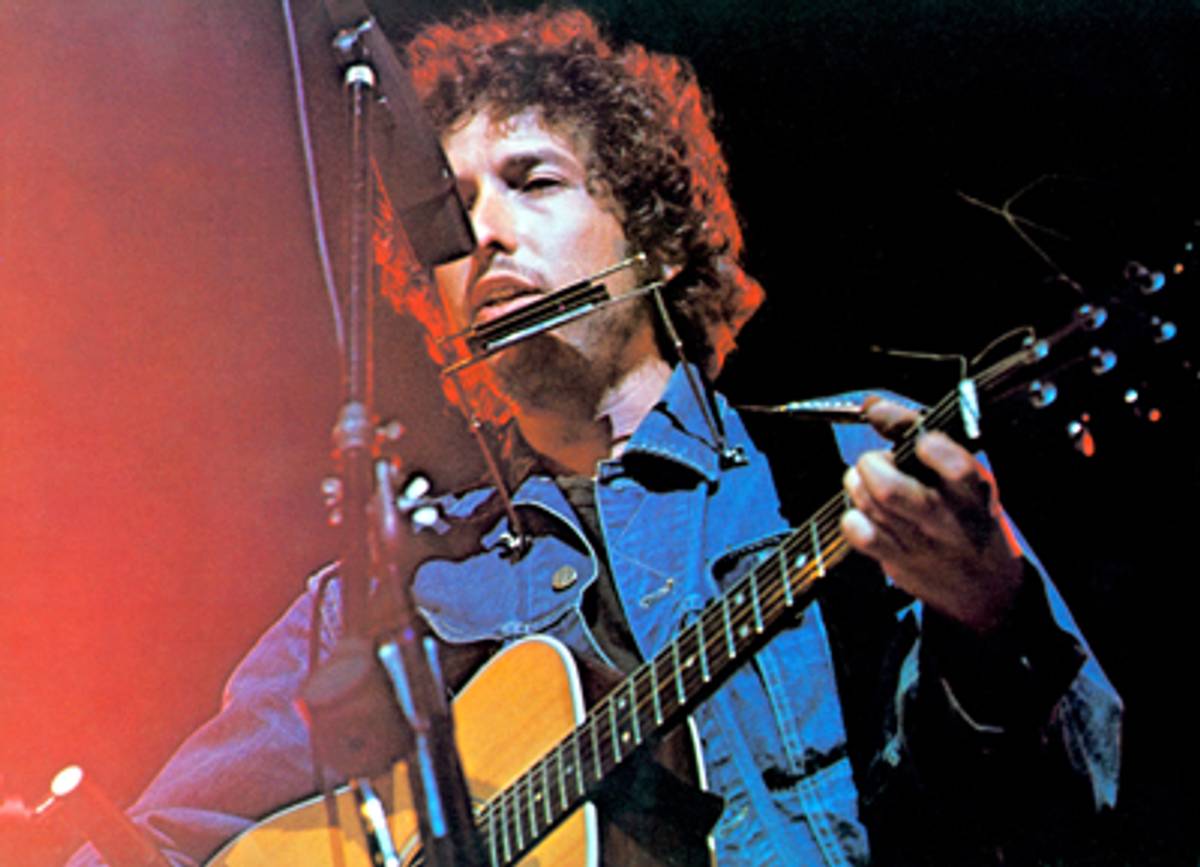

There was one moment, though, that managed to penetrate my cloud of anxiety. An hour into the show, Dylan dismissed his backing band (the Heartbreakers), so he could perform an acoustic set, just him and his guitar. The first song he played was “Masters of War.” No sooner did he begin than we heard a dull roar overhead. It grew louder as Dylan sang:

Come you masters of war

You that build all the guns

You that build the death planes

And just then—I mean, even as the words were coming out of his mouth—a C-24 transport plane banked over the amphitheater, its massive belly passing no more than a few hundred feet above where we were sitting. The crowd let out a collective gasp.

It was clear to me now that I had somewhat underestimated Dylan. I still didn’t quite get why so many people worshipped his music. But I now understood—with something of a jolt—why people worshipped him. Dylan had some very powerful mojo.

You’ll be relieved to know that the Freak Archives do not contain an extant copy of the subsequent review. It was everything you’d expect from a 19-year-old sports intern. There was no appreciable criticism of his music, more a string of adjectives and song titles, several of them wrong. (I referred to “Ballad of a Thin Man” as “Mr. Jones.” Nice.)

But the experience was exhilarating, nonetheless. It was enough to convince me that perhaps sports reporting wasn’t my only option, that, in fact, music criticism might be more my thing.

My transformation from sports geek to music geek didn’t happen overnight. It was gradual, just like my conversion to Dylanism. I quit the soccer team and became a DJ at the college radio station. A couple of years later, I graduated and took a job as a features reporter in El Paso. One day, not long after I arrived, my editor asked me if I’d ever reviewed concerts before.

“Are you kidding?” I said. “I reviewed Dylan back in ’86.” Then I told her the story about the plane swooping over the amphitheater, which—along with the fact that my editor had no other real options—landed me a job as the paper’s music critic.

I certainly owed Dylan big time for this. But I still wasn’t what I’d call a fan. I had a few of his albums. Still, the hardcore obsessives, the dudes who parse his lyrics as if they were written on a Dead Sea Scroll, struck me as sad. I frankly still didn’t get what they were so worked up about.

* * *

A decade later, I found myself on Folly Beach, outside Charleston, South Carolina. I was ostensibly visiting my uncle Pete, who was filming a documentary on Reconstruction. But really, I was in full retreat from my life, which I’d mucked up pretty thoroughly.

I was supposed to be in Greensboro, North Carolina, having fled newspapers for an MFA in creative writing. But grad school wasn’t going so well. Everybody there seemed to hate me, especially my professors. What’s more, I hated them. I didn’t want to go back.

Pete said he understood. I didn’t have to stay there. There was no law. Then he slipped me a copy of the Dylan record he was listening to at that time, Saved. As Dylan fanatics will happily inform you, Saved is the second of his three born-again Christian records. In other words, obscure and not well regarded.

But Pete had always been something of a guru to me, so I placed my trust in him and popped the cassette into my car stereo anyway, and listened to it all the way back to Greensboro, in a state of swelling rapture.

Dylan’s lyrics were those of an evangelical looneybird—he talked lots about the blood of the lamb—but the music was lush, insistent, and absolutely heartfelt. He threw his pinched and whining voice right out there, against bubbling organ riffs and a full gospel choir. The title track hit me hardest. It was a rousing anthem built for tent revivals. Dylan’s words spoke to my precise spiritual condition:

Nobody to rescue me

Nobody would dare

I was going down for the last time

But by His mercy I’ve been spared

Much has been made of Dylan’s starring role as the Judas of Modern Jewry. How he leaves Hibbing, Minnesota as an obedient Zimmerman and washes up on the shores of Greenwich Village, with a bogus Woody Guthrie accent and a new name inspired by a Welsh poet. How he gets himself washed in the blood of Christ, then tacks back to Judaism. It would be a fool’s errand to argue against his spiritual confusion.

But I could give a rat’s ass about another man’s faith, as measured against his imagination and candor. Which is the very reason Saved hit me so hard. What Dylan was saying, what he was saying (as I understood things) to me was this: There is no shame in true belief. You must soldier on in the face of doubt, for doubt is not just the proof of your faith, but a joyous cause.

He was talking about his shiny new savior, and that was kind of creepy. Sure. But the larger lesson was one of mercy. I needed to forgive myself, not my enemies. There was no other way to survive the days, with only my suckass prose for company.

More years went by. I moved up north and set about writing short stories. The big money sector—that was my grand idea. I wasn’t ready to start proselytizing for Dylan, but I amassed a decent collection of his records, and his songs continued to come to me, as necessary.

I indulged in a frantic live version of “Maggie’s Farm” upon my liberation from a particular dismal literary agent. I binged on “Man of Constant Sorrow” during the first of my annual winter depressions, trudging the dirty snow to the rhythm of his plucked and descending minor triad. Upon the implosion of the modern electoral system—I refer here to what the historians still call the 2000 Presidential Election—I listened to “Everything Is Broken” 271 times in a row. (I can no longer suffer the song without an accompanying surge of nausea.)

These were but infatuations, with their zippy mood and velocity. But Dylan had big things in store for me. Yes, he did. Five years on, deep into my thirties, I found myself still alone, crashing into the wrong women, or treating the right ones as if they’d been leased. The writing had finally gotten on track a little, but this hadn’t made me any happier, or any more pleasant to be around.

One day I was sitting around, marinating in self-pity, when the phone rang. The voice on the line was my old friend Tom, a devoted sadsack who, oddly, looked remarkably like Dylan from certain angles.

“You know what’s great?” he said to me.

There was no introduction necessary. I knew his voice well enough, though his tone was frighteningly placid.

“No,” I muttered. “Tell me.”

“Listening to Bob Dylan with your daughter,” he said.

In the background, I could hear the gentle chords of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” Then an image came to me, quite clearly, of Tom lying in his basement with his baby daughter sprawled on his belly. He sounded at peace, in a way I’d never known him to be, Tom with his disappointed brow, his soft complaints.

Is this what family life might be like?

I had always assumed (without quite realizing I was making this assumption) that a family of my own would return me to the wordless, loveless feud that marked my own upbringing. But here was Tom—every bit my equal as a commitment-phobic depressive—suggesting that the finding of a wife, the spawning of a child, might in fact produce scenes such as the beatific one inside my head.

And it wasn’t just Tom. Dylan was saying the same thing, even though his lyrics were about ditching a lover and walking off into the sunset, because, the thing is, as I sat in my empty apartment imagining the warm embrace of Tom and his daughter, I realized that this wasn’t just another kiss-off tune, but that Dylan was himself in despair, aware of his failure before the great task of love, dreading the solitude that awaits him and—just beneath his tone of casual dismissal—desperate for absolution:

And it ain’t no use in turning on your light, babe

I’m on the dark side of the road

Still I wish there was something you would do or say

To try and make me change my mind and stay

We never did too much talking anyway

So don’t think twice, it’s all right

And I, too, was on the dark side of the road, listening to that bittersweet song of my own heart, and Dylan was saying: Take a look around, bub. Is this really the way you want to lead your life?

I will spare you the long version of what ensued, which involves a lot of air travel and therapy. The short version is that I now have a daughter of my own, along with a dim basement where we listen to Dylan through the broiling summer afternoons.

* * *

Do I read a bit too much into Dylan? Probably. He provokes this sort of exegetical excess. He doesn’t mean to, exactly. Not in the same way the authors of the Bible do. Those guys—they wanted to play God. They wanted to instruct people morally. With Dylan, it’s more a case of chronic self-examination, which seems to run in his blood. He also writes very beautiful melodies, the kind that seep into the tender parts.

I am not suggesting that Bob Dylan has magical powers. His gift is for pop music, not prophecy. His songs cannot cure the ill, or redeem the damned. They merely provide us an occasion to heal ourselves. They unlock the transformative aspects of belief within us. That’s what Dylan has done for me since I discovered him 20 years ago. He may not be much of a cantor, but he’s a helluva rebbe.