Second Avenue Elevated

Looking for tracks to my father’s unobtainable past, in old Jewish New York

My father was a cardiologist. In his top desk drawer he kept a stethoscope, a blood-pressure cuff, and stainless steel calipers with needle-point tips. The calipers were a mapmaker’s tool. Arms apart, they took measure of his patients’ echocardiograms—opaque, ultrasound images of a beating heart in space and time. Sometimes I would try on the floppy armband and pretend to guess my own blood pressure. The hand pump was a bloated racquetball. A few quick squeezes brought the instrument to life, fattening the armband with air while the red needle danced and jiggled with equivocation. Thereafter I had no idea. I could squeeze, inflate, release—just like my father did—but I had no inkling how these actions fit together. It was like shuffling and dealing a deck of cards without the first clue how to play poker.

At 5:30 each morning he left home with a quick shave and a slap of cologne but no shower. Sometimes I would hear his dress shoes on the front paving stones. Sometimes it was the muffled clap of the car door that awoke me. The starter winced—a begging that lasted several seconds until the engine turned over—and a fast shot of gas kept the car from falling back asleep. A strobe of headlights grazed my window shades as the tires reversed themselves over loose gravel. I knew, as my father drove off for the expressway, that his commute time would double or even triple if he left any later. What I never understood was how he could drag himself away so early without first dragging himself under hot water.

His preference was to take baths the night before. He considered it a much more satisfying ritual at the end of his long day—and why not? Where else could a man go to be alone in his own house? Where else could he go to escape the ambient noise of the television, or to avoid talking with his wife?

“I’m taking a baah-th,” he announced on his way upstairs, affecting the voice of an Englishman. Ours was a split-level house. We had no master bathroom, only a second-level bathroom that was next to my brother’s room and down the hall from my own. I heard three cranks of the faucet from inside, followed by the blast of water on porcelain. The water pooled in the tub with a low chugging sound, like that of the washing machine. When my father stepped back into the hallway I instantly popped out to greet him. “Off with the dungarees,” he said. He turned, tugging on his tie, and marched the remaining seven steps up to his bedroom, where he shrugged off his good clothes and scanned his bookshelves for something to read.

From his distant world of the hospital, my father slipped seamlessly into his solitary life back home. His habit of reading was formed in childhood, where he’d fallen under the spell of such books as The Wind in the Willows, There Was a Child Went Forth, and the complete works of Sherlock Holmes. In college he squeezed his pre-med requirements in between classes in history, philosophy, and the “Great Books” curriculum required of all Columbia students. On the toilet, in the leather chair of his bedroom study, or in the steamy, sequestered chamber of the bathtub, he read oversized books on the Celts, the Middle Ages, and World War II. He burrowed into Edmund Wilson’s biographies on the Thirties, Forties, Fifties, and Sixties; into the collected letters of E.B. White. One of his favorite books was Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale, which he read so many times that the soft cover permanently curled away from the other pages.

In the hallway, over the sound of the humming vents, I knocked softly and waited. No answer came, so I tried again—a little bit louder the second time. His mumbled reply I mistook as an invitation to enter.

“Yes?” he asked. His eyes slowly unfastened from the book he was reading. The splayed cover spread across his chest like a tanning reflector.

“Be careful—” I said, and pointed to the bottom edge, which sat dangerously close to the waterline.

His stomach made a small knoll above the surface. Beneath the water, the curve of his belly broke suddenly in a double image, his nakedness a few inches south.

“It’s fine,” he answered, as his eyes drew back to the book. It wasn’t from concern so much as the pull of the next sentence. In a few more seconds he seemed to forget about me. That was it—that was the beginning and end of our exchange. A sad and funny one to think about. A son intrudes on his father in a private moment, but to what end? What type of connection was he hoping for? And the father—he acts as though the sole reason for his son’s visit was to warn him against soaking his book. I mumbled a quick goodbye on my way out, and from beyond the door came the persistent humming of the bathroom vents.

***

History was more than a subject of books for my father. He was constantly invoking the past in his everyday life, as if to color in the lines of the present-day world. When my brother was an infant his lower lip jutted out involuntarily, a mannerism my father likened to Winston Churchill. In imitation he would squint his eyes, turn out a shiny lip, and offer—in a gruffed-up voice—the prime minister’s famous declaration: “We shall neh-vah, surren-dah, hrmph!” It was my father’s version of Churchill’s speech to the House of Commons, in June of 1940, before the Battle of Britain. My father was only 4 years old at the time, so it had been much later that he heard a recording of the actual speech. My own likeness, he claimed, was to Woodrow Wilson, as I had the president’s thin face and square jaw.

My father had another foot forever planted in the past. He’d grown up in New York City in an era when the Yankees were synonymous with baseball, and baseball itself was still synonymous with America. Back then everyone had seemed more connected to one another, either by the neighborhoods they lived in or the programs they all listened to on the radio. In my own suburban childhood north of Chicago, that kind of connection seemed fleeting. People walled themselves off in large houses behind spacious front lawns; they drove cars on even the shortest of errands. It was true that technology made people more accessible in my day—fax machines and computers could hurtle us miles away in a matter of seconds—but I couldn’t say whether that technology made the world feel smaller, or simply the people who used it.

My father used that technology as well. He wore a pager on his hip, carried a portable phone in his car, and got to know computers through work. Yet these were merely instruments to him. I had the impression that my father only turned to them on an as-need basis. He never developed my own generation’s dependence on the latest gadget, or our fixation on the next life-changing invention.

The few television programs that interested him were on Channel 11, Chicago’s public TV station. The anthem for Masterpiece Theatre I easily recognized, its regal trumpets as unmistakable as the British accents or self-flattering dialogue. Occasionally, during dinner, my mother would announce an upcoming performance by Mark Russell, a political comedian who stood on stage and told jokes to a live audience before he strolled over to his piano to play satirical songs. My parents had such a rollicking good time watching these performances that I often joined in as well, even though I was too young to understand what made Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, or Tip O’Neill so funny. Wasn’t it comical enough to see a middle-aged man in a bow-tie standing—rather than sitting—at a blue-painted piano decorated with white stars?

The other time we watched TV together was during the public television’s weeklong fundraising drives. It seemed like every year the station would run some kind of documentary on the Second World War. In our family room my mother sat at one end of the fabric sofa, I at the other. On the screen, Germany’s Afrika Korps was being pushed back by the British Eighth Army. Rommel, the Desert Fox, had retreated from Egypt all the way to Algeria, some 1,750 miles, where he met the British First Army and a division of Americans. In a later image, General Eisenhower was shown riding in a jeep with General Omar Bradley, the two men inspecting U.S. positions in Tunisia.

My father sat cross-legged on the floor, rocking back and forth as he chewed his tongue. He was so close to the TV that the light reflected off his face. His hands anxiously scratched each other. His knuckles were like walnuts; his skin chafed from the bite of his fingernails. “Stop it,” my brother and I both said. His agitation filled the room; it was as if he were receiving reports directly from the front lines. “Phil—” our mother scolded, and he finally glanced up in self-awareness. He pulled his hands apart and stifled them at his sides, only to resume scratching again a few moments later.

***

Most of what we watched on television, my father had actually lived through. He was born in 1936 and grew up at the end of the Depression. To someone who’d never experienced it, the very word “Depression” had a romantic flavor. It evoked images of apple sellers in the streets, of people shining shoes, taking odd jobs, and doing whatever they could to survive. I envisioned a frontier spirit in my father’s day, an attitude reminiscent of America’s earliest settlers. The pictures I saw all seemed to communicate the same message: out of great hardship, its opposite was born. I believed such low points were crucial to our country’s self-examination, like a collective ladder we used in order to elevate ourselves. This was a safe, easy notion for a suburban child to have, particularly one who’d never been part of the climb.

My father had been. He was too young to fight in the Second World War, but he’d been alive to witness the last of the great emancipators. He described a newsreel he’d seen of FDR and Churchill talking, when he was 5 years old. He thought their voices sounded out of the ordinary—“not like people you met on the street,” he said. “It was as if they had bread in their mouths.”

Later, while he was a medical resident, my father served as an officer in the Navy. He was drafted in August of 1961, after the Soviet Union closed off East Berlin, though he didn’t receive his commission until July of 1962, almost one year later. Only a few months afterward he heard rumors that America was going to war. His destroyer, the U.S.S. Buck, had been docked in Seattle that October, during the World’s Fair. Kennedy was scheduled to visit them on a Sunday, but at the last moment he mysteriously called off sick. Everyone became suspicious. On Monday, news broke out about the Cuban Missile Crisis. Just before his destroyer shoved off, my father had called home to tell his mom goodbye. He said he didn’t know when they would talk again.

To me it sounded heroic. My father had been cast in one of the great installments of the Cold War. Experience told otherwise. In the end, their destroyer had only been sent to Treasure Island, in San Francisco Bay, on orders to protect the Golden Gate Bridge from enemy ships. For two weeks my father took day trips into San Francisco, while the bridge remained safely guarded from Fidel Castro and the Soviets. Stories such as these, which I grew up hearing and rehearing, left me feeling cheated by my own birth. I was a late arrival to the 20th century: I’d been relegated to a prosperous and unpolemical age, whereas my father was the product of a glorified past.

It was a past he remained devoted to. His two greatest passions were baseball and the New York City transit lines of his childhood. Surprisingly, he was not a Yankees fan. As a boy he’d been to Yankee Stadium, but his interest in baseball grew out of the first World Series he ever heard on the radio. This was in October of 1945, a couple years after his family had left Manhattan and moved to Forest Hills, Queens. In that series the Detroit Tigers were taking on the Chicago Cubs (our very own Cubs!). At P.S.3 (Public School Three, this stood for), his Phys Ed. teacher, Mr. Dufferin, had the game turned on. “All the boys listened to the series,” my father said, “all the girls were sewing.” That series went the distance—a full seven games—with the Tigers eventually defeating the Cubs, and with my father becoming a lifelong fan. He chose wisely. The Cubs would not make it back to the World Series until 2016, more than 75 years later.

Most nights after dinner he would check out from the rest of us. Rooted to his desk chair, he would pour over enormous baseball encyclopedias with tissue-thin pages. Over his shoulder I saw a cascade of figures and numbers that were hoarded into various alignment. The massive book sat humped in front of him, a sallow light shone from the desk lamp, and he hunched forward like some medieval scribe. On a large legal pad he copied down pages upon pages of these statistics. He never saved the sheets themselves, but he remarkably held on to the information. He knew home run titles, batting averages, pennant winners, win-loss records of pitchers that went back many decades. He enjoyed being tested on all the great players: the Tigers’ Hank Greenberg, “Doc” Cramer, and Hal Newhouser; the Yankees’ Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, and Phil Rizzuto; and from the old Brooklyn Dodgers, Gil Hodges, Duke Snyder, and Jackie Robinson. He was a giant receptacle of facts, which included hometowns, birthdates, and funny stories. My high school homeroom teacher was from Anderson, Indiana, a place my father never failed to remind him was the same hometown of Carl Erskine, a right-handed pitcher for the Brooklyn and then Los Angeles Dodgers.

Casey Stengel, the Yankees manager from 1949 to 1960, was another common reference. Like Yogi Berra, he was famous for his quizzical and often humorous statements. My dad mentioned an interview once in which Stengel was asked whether staying away from alcohol helped baseball players. His answer—only if they could already play. In another story, the manager was said to have approached his left-fielder in the dugout one day, saying he had some “news” that might interest the man. After a moment, Stengel turned casually to his player and said, “Well, one of us has just been traded to Kansas City.”

The stories my father told were more interesting than the straight facts, but he always seemed to care more about the trivia. He begged to be quizzed on dates and figures. Sometimes he would recite these in public or in front of my friends. “What else?” he’d say. “Ask me more.” He became ravenous. Once the data started pouring out, he lost all self-control. My mother rebuked him for showing off. My brother and I both became embarrassed. And still, no matter how annoying he got—or how often we intervened to pull the plug—we all retained a secret pride in him. It was hard, in spite of this overbearing behavior, not to be awed by his immense knowledge.

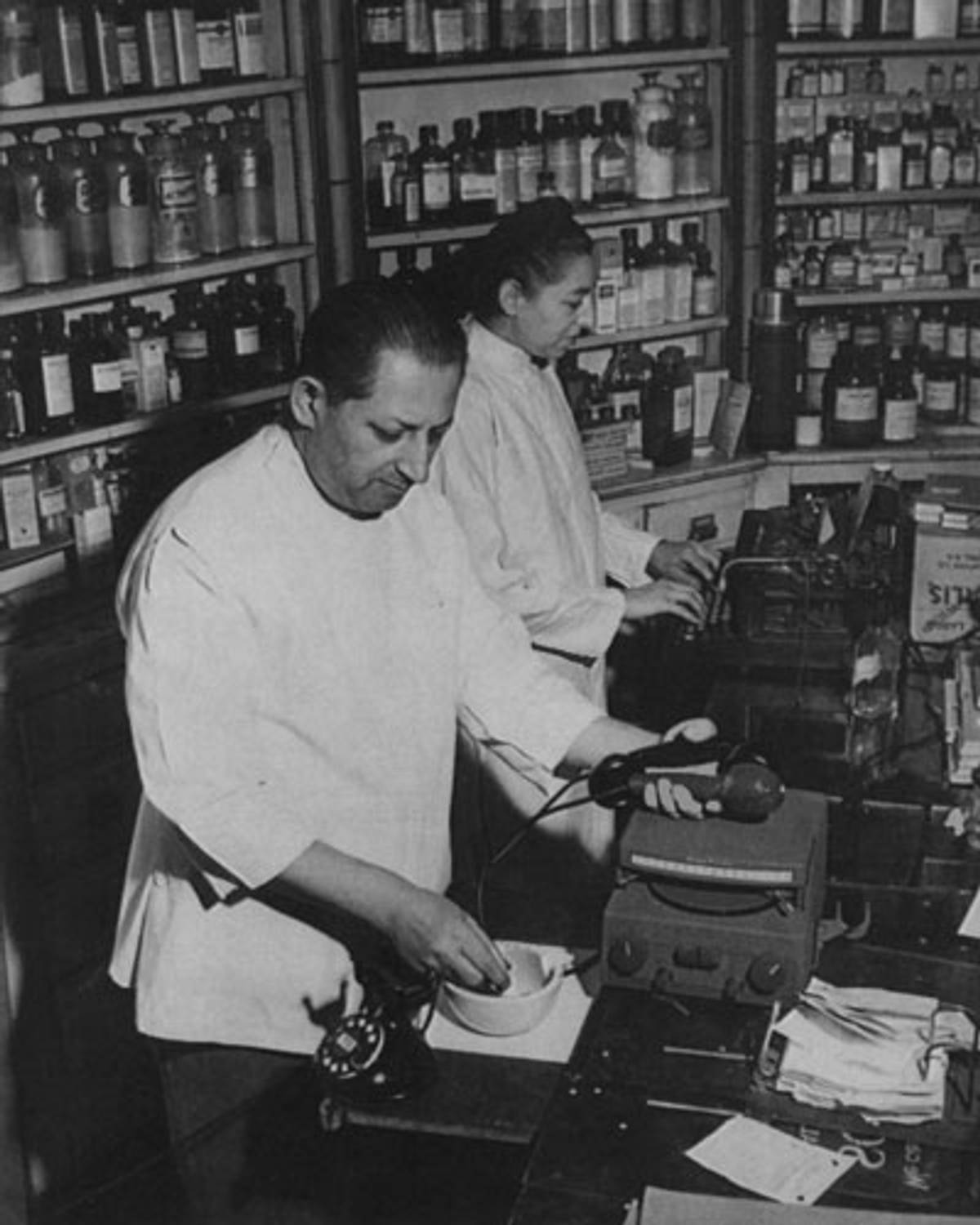

Below the baseball encyclopedias, the bottom shelves of his twin bookcases were lined with such titles as New York in the Thirties; Lost New York; The Manhattan Elevated; Alfred Stieglitz and New York. The tall hardcovers had inch-thick bindings; a single book could stand freely if I nudged the cover open the slightest bit. These books told stories of the subways and elevated trains that had been around in my father’s lifetime. The one he most often referred to was a thin, modest-looking softcover, on the Second Avenue El. The cover photo showed the 50th Street Station facing north. “Pickwick Pharmacy was one block away,” he told me. That was my grandfather’s old drugstore, on 51st Street and 2nd Avenue. My grandfather had bought the pharmacy in 1920, inheriting the name “Pickwick” from the Pickwick Arms Hotel, just down the street. “John O’Hara lived there,” my father said, with great import. I didn’t tell him I’d never heard of the author, let alone read any of his work. But I had heard of another famous writer from the neighborhood. John Steinbeck lived on 51st Street in the early 1940s, though my father himself hadn’t known this at the time. He never suspected, when he saw the film Tortilla Flat advertised at the local movie house, that the author himself lived just down the street.

Numerous celebrities frequented Pickwick Pharmacy. When my father was 5 years old, someone entered the drugstore wearing a sharp suit and fedora, and the entire pharmacy went quiet. Everyone stopped to gawk at the person, and my dad turned to his father to ask who the important-looking man was. My grandfather bent down with some embarrassment and said, “Greta Garbo.” Years later, in his mid-20s, my father would see Anthony Perkins on occasion. He was acquainted with the actor’s family, and one time he innocently asked the man how his mother was doing, only to be laughed at. My father didn’t know the movie Psycho had just been released. Likewise, he had no idea about the old lady Norman Bates had kept hidden in his attic.

His first apartment in the city was at 311 51st Street, less than a half block from Pickwick Pharmacy. “Three hundred and six feet away,” my father stated. He cited the figure as though he’d measured it, door-to-door, on his hands and knees. The number would stick in his head like all the other dates and facts he recited; it became as incontrovertible as the batting averages or win-loss records found in any of his encyclopedias. In 1941, his family moved a few blocks away to East 48th Street between 1st Avenue and the East River. They would stay there another two years before moving again, this time to Forest Hills. That second apartment no longer exists. It was torn down to make way for the United Nations

***

Close to those first two apartments was the Second Avenue elevated, a train for which my father developed a special affinity. On the soft-cover jacket of his book, in the foreground of the picture, a one-story rectangular cabin stood at the edge of the elevated platform. That was the switching tower. It was used to send trains back to Queens. Just beyond the tracks, a blank white billboard framed the top corner of an apartment building. My father recalled how he and his friends would watch from the street as men on raised platforms periodically repainted the sign. “Every couple of months they would change the ad,” he said. “But it was always for Sunkist oranges.” I wondered if this could really be true. The same product—but a different ad—each and every time? But I had no proof against my father’s memory.

As a young boy, my father and his family would take the Second Avenue line to Coney Island. He was very particular in recounting his journey. The El cost 5 cents back then. At Park Row, in lower Manhattan, they changed to the Culver elevated line of the BMT (short for Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit), which crossed over the Brooklyn Bridge. He was too small for the rides at the amusement park (except the merry-go-round), so he and his parents spent most of their time at the beach. They also took the Second Avenue El to see the 1939 World’s Fair, in Flushing Meadow’s Park. For this they rode in the other direction, crossing over the 59th Street Bridge into Queens.

Every few months, my father told me, he and his parents would take the El down to the same delicatessen on the Lower East Side. That was his father’s old neighborhood. My grandfather had lived on Rivington Street, an area that in the early 20th century was teeming with Jews and dotted with synagogues. (Many of those old synagogues remain, though they’re now defunct.) According to my father, the deli wasn’t anything grand. He described a corner entrance with tables along each street-side window, an unswept terrazzo floor, and large salamis strung up above the deli counter. He never ordered corned beef, pastrami, or any of the other delights you might expect. He always ate “the special”—which was nothing more than a large hot dog. I asked him: Why such a fancy name for something so simple? My father had no answer. He ordered two specials with a side of fries and Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray Soda, a celery-flavored soft drink that came in a can.

My father enjoyed the food but not the delicatessen. The restaurant—in fact, the entire neighborhood—made him uncomfortable. At the deli, the female waitress would hurry around shouting the customers’ orders at the top of her lungs. “I didn’t understand why she had to yell so loud,” he said. “She wouldn’t stop.” (Forty years later, that same deli would pass into popular culture, as another woman’s screams were famously depicted there in the movie When Harry Met Sally.)

Afterward, as he and his parents walked the Lower East Side, my dad was put off by the bustling, inhospitable streets. “Sunday was the busiest day,” he said. People with raised voices rushed in all directions, the streets were even more crowded than the deli. He and his parents wandered past stores selling tobacco, housewares, and clothing. Everything about the neighborhood seemed foreign to him. Vendors sold pickles from wooden barrels, store windows were painted with indecipherable letters, and the Jews—with their black clothing, hanging tzitzit, and ringleted hair—looked nothing like the Jews he knew.

“We were different from them,” he told me. “My father had come from there, but he was a quiet man. He dressed neatly and he never rushed.” The ‘there’ he meant was the Lower East Side, but somehow I suspected he was talking about someplace else. I attributed his distaste to the Eastern Europe from which his ancestors had hailed, and the shtetls in which these Jews once lived. That certainly explained my own revulsion. These ghettos were a blemish on our past, and it baffled me why Jews would cross an ocean and resettle in the New World, only to import that same old culture with them. What was the point in speaking a strange tongue and wearing strange clothing that divided you from your fellow countrymen? To see pictures of those neighborhoods reminded me of the atrocities that had befallen so many of their relatives back in Europe. And it seemed, in some dark corner of my mind, an invitation to the same kind of treatment here. The documentaries on TV gave profound glimpses into that mistreatment. I shuddered at the images of rail-thin people who were barely human looking, wearing striped vestments adorned with the Star of David. How frightening to think that this frail condition—their bodies reduced to scarecrows—was actually the lesser of evils awaiting them.

During my father’s childhood, people were certainly aware of Hitler. Everyone talked about the war in Europe, but the real horrors taking place in Germany and Poland were still largely unknown. In reality, and in the worst of anyone’s imagination, such horrors remained unfathomable.

For my father, one of the great casualties of the war, albeit unrelated, was the closing of the Second Avenue elevated. The portion that ran above 59th Street shut down on June 11, 1940, one year after the World’s Fair. “That was the day the Germans entered Paris,” said my father. He’d been 4 years old at the time. “It was the same day that Italy declared war on France,” he added. My father copped Churchill’s voice again. He spoke in a low, bit-off snarl, calling Mussolini a “whipped jackal” who came “frisking at the side of the German Tiger with yelpings of triumph.” The imitation, I thought, sounded vaguely like W.C. Fields. On June 13, 1942, the rest of the Second Avenue El shut down. It was one week after the Battle of Midway, my father informed me.

Many years later, I would finally hear a recording of Churchill’s voice. I remember the audio quality being poor. Through rumpled static he sounded less commanding than what I had expected—certainly not the voice you’d associate with such a hulking figure. And yet it was impossible not to be moved by his words. As Churchill drew toward the end of his speech, I felt stirred by a growing sense of anticipation. The prime minister declared: “We shall fight in the fields, and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills …” My ears perked up. I awaited his exclamatory hrmph!—except … it never came. Had I missed it? I replayed that portion, straining to hear through the background muck, but it wasn’t there. Finally I had to face reality. The exclamation had either been an invention of my father’s, or else he must’ve grafted it from another of Churchill’s speeches.

I never mentioned this to him. It would’ve been wrong to call out the mistake—like contesting a history that wasn’t mine to begin with. My father’s version remained as true to him as any of the dates or events etched in his mind; as real as any of the old photographs from his books. To him, those photographs bore an animation beyond the page, just as Churchill had been an actual living figure in my dad’s lifetime. To me, the images were something out of folklore, while Churchill was no more than a symbol from a bygone era. He was like Eisenhower and Kennedy, names I grew up associating with Chicago expressways and daily traffic reports as much as with great presidents. To this day, the name Midway still evokes a distant, hard-to-reach airport on Chicago’s South Side more than the famous battle it was meant to honor.

Pickwick Pharmacy, the Second Avenue elevated, his father Edward—these were all ghosts to me. I felt no more attachment to a grandfather I’d never met than to the drugstore he’d owned. “You have his hands,” my dad insisted. “I’m telling you—you do.” But he was only half-speaking to me. The rest of his attention lay elsewhere, in a backward glance I could never share with him. His past was as removed from me as his long days at the hospital or his many hours in the bathtub. I both envied and resented him for his connection to history, in the same way a poor man envies and resents the rich, for all their unobtainable possessions. In spite of all the tales I heard about New York City, I couldn’t imagine a pharmacy in place of the sleepy Italian restaurant now occupying his old street corner, or a throng of Jews supplanting the vast swarms of tourists at Katz’s Deli, or the Brooklyn Dodgers ever playing anywhere but in Los Angeles.

Jonathan Liebson teaches writing and literature at The New School and NYU. His most recent work appears in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and The Texas Observer.