Serbia’s Holocaust Memorist

Danilo Kiš’s fiction, newly translated, mined the Shoah with a Borgesian sense of mystery

In Danilo Kiš’s short story “The Knife With the Rosewood Handle,” the narrator claims that his tale “has only the misfortune … of being true,” but “to be true in the way its author dreams about, it would have to be told in Romanian, Hungarian, Ukrainian, or Yiddish; or, rather, in a mixture of all these languages,” along with some Russian. The instruction sounds airy, a tad scholarly. But, as we soon find out, this is a murder story: The languages come out of a woman as she is being stabbed to death. She speaks “in Romanian, in Polish, in Ukrainian, in Yiddish, as if her death were only the consequence of some great and fatal misunderstanding rooted in the Babylonian confusion of languages.” They ultimately give way to “Hebrew, the language of being and dying.”

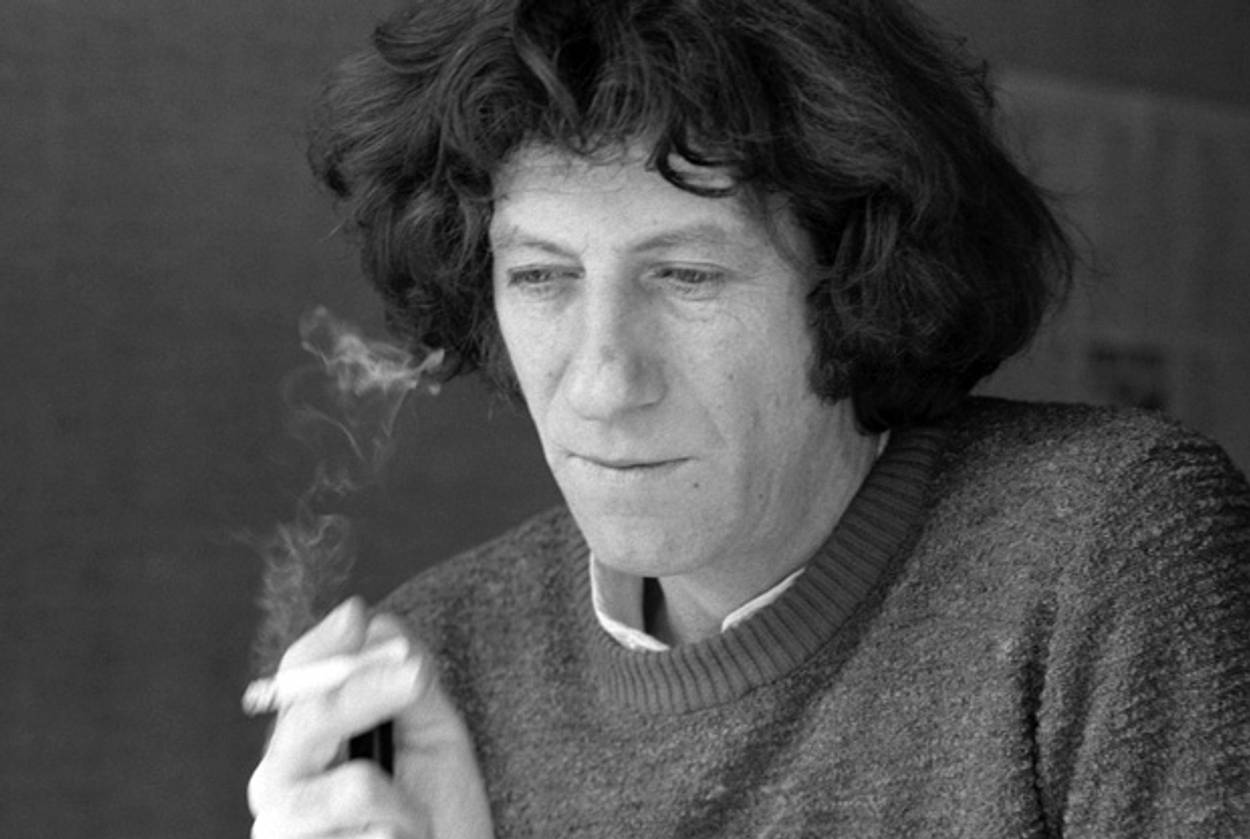

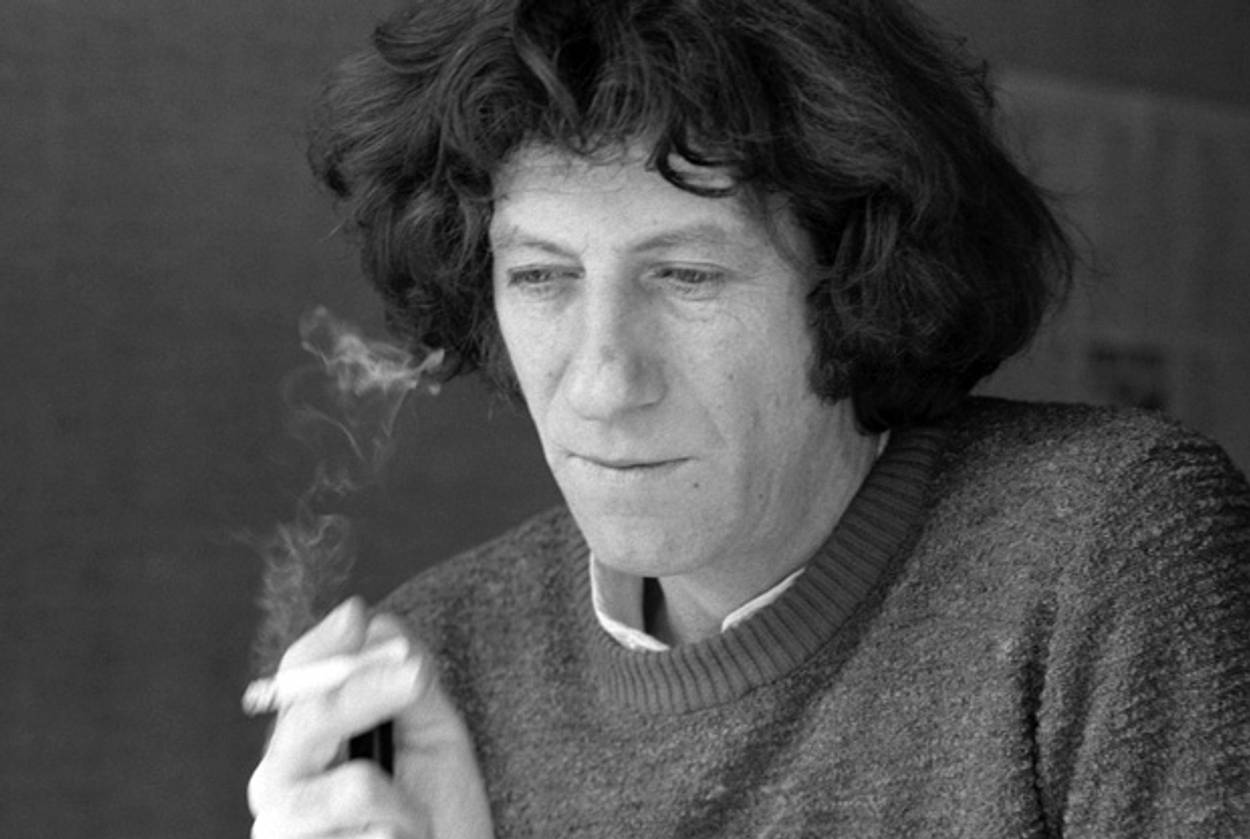

This slyly gruesome scene is a good place to get a sense of the writing of Danilo Kiš, a Serbian born to an Eastern Orthodox mother and a Jewish father who, despite being baptized, identified as Jewish. The light but menacing ironic touch; the Babel (and babble) of tongues; a sudden, violent death somehow made strange; and a metaphysical Jewishness—these were key elements for Kiš, who emerged from the ruins of postwar Yugoslavia to become a major figure in Central European fiction. Mixing a modernist sense of history with Borgesian invention (though, like Leibniz and Newton coming to calculus, Kiš may have arrived at his style independently), Kiš fashioned a distinct polyglot literature, one that presented original responses to the dual terrors of Soviet communism and Nazi fascism.

Kiš remains far too unknown in the United States, despite being championed by the likes of Aleksandar Hemon, William Gass, and Philip Roth, who helped to introduce him to the English-speaking world by including him in his influential Writers From the Other Europe series. In 1980, under Roth’s editorship, Penguin published Kiš’s story collection A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, which included “The Knife With the Rosewood Handle.” Since then, amidst a period when major publishers have shown fitful interest in foreign fiction, Kiš’s work has been shepherded by university and independent presses. Several of his books remain untranslated, but this month, Dalkey Archive will publish new translations of two short novels and a story collection—The Attic, Psalm 44, and The Lute and the Scars—that offer an important chance to reassess his work and return him to the front ranks of world literature. What emerges most poignantly is the theme of inheritance, both literary and historical, and of how Kiš hacked through the thicket of memory to find, if not solace, then a tenuous accommodation with the past. In his writings on the Holocaust, Kiš also produced some precocious insights about the nature of remembrance and its potentially malign influence on art.

***

Kiš was born in 1935 in Subotica, a formerly Austro-Hungarian city that had recently become a Yugoslav border town and that featured one of Europe’s grandest synagogues. In 1944, Kiš suffered an early loss when his father died in Auschwitz. He and his remaining family rode out the rest of the war in Hungary (the homeland of his father, whose surname was originally Kon), before resettling in Montenegro. Kiš later graduated from the University of Belgrade and spent many years in Serbia, but he also taught in Hungary and France, where he mixed with a host of survivors and émigré intellectuals. He spent his last decade in Paris and died there of cancer in 1989.

In Yugoslavia, Kiš suffered abuse from the local writers union, whose hardline Stalinist members accused him of plagiarism, a charge that stemmed both from his Jewishness and from his being out of step with the dogmatic school of socialist realism. (He also tended to trumpet his non-Yugoslav influences, providing some ammunition for his nationalist critics.) In his introduction to A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, Joseph Brodsky says that this treatment was enough to send Kiš into a “nervous shock.”

Among the newly translated works published by Dalkeyis Kiš’s first novel, The Attic. Written in 1960 and subtitled “A Satirical Poem,” the book is the story of a young writer living a bohemian life in Belgrade, where he courts a woman he calls Eurydice and lives in an insect-infested apartment. The novel has some witty moments, but it’s a scattershot collage, its varied parts less coherent and appealing than his later work.

The Attic is most interesting for what it reveals about how Kiš evolved as a writer. Like many first novels by young men, the author sings of himself, in the form of his fictional alter ego. But his first-person protagonist does so with a deprecating self-consciousness: “I was completely caught up in myself—that is, caught up in the vital issues of existence.” He then unleashes a long list of these concerns, ranging from “the issue of nourishment” to “the difference between culture and civilization.”

The novel also features some strange (and potentially illusory) journeys to Africa—in which Africans are a little too exoticized for comfort—and ends with the narrator, who sometimes calls himself Orpheus, running a seedy bar with his roommate. This is Kiš in the lab, messing around. Lists, pastiche, cosmic concerns set alongside the trivial—many of the tropes that would later serve Kiš so well are here, though noticeably absent are the death and historical trauma that would become the dark stars at the heart of his oeuvre.

“Haven’t I told you a hundred times that I am writing in order to emancipate myself from my egoism?” asks the novel’s Orpheus. It’s a canny remark—at once bombastic, self-flagellating, and sincere. But the other two newly translated Kiš works—the story collection The Lute and the Scars and the Holocaust novel Psalm 44—show that, if anything, his emancipation led to a new imprisonment, this time in the shadow of totalitarianism and genocide.

***

Written in 1960, Psalm 44 is not Danilo Kiš’s only Holocaust novel. (Garden, Ashes is about a boy whose father, a deluded genius, former railway worker, and failed businessman, is carted off to a camp. Hourglass is about an assimilated Jewish railroad inspector in wartime Yugoslavia. In both cases, Kiš makes heavy use of railroads—among the most loaded symbols of the war.) But it is his only one about Auschwitz, which claimed the lives of not just his father but also several other family members. And for its time (a generation removed from the Shoah, when the author was still in his twenties), Psalm 44 is a startlingly mature work. Based on a newspaper article about a child allegedly born in Auschwitz, the novel seizes on its maudlin premise without becoming mired in it.

Psalm 44 takes place mostly during one anguished night as Marija, a camp prisoner who has secretly given birth to a boy, plans an escape with her friend Zana. The prose unspools in long, feverish sentences as Marija watches another prisoner, Polja, dying in a nearby bed and wonders whether they are betraying her by fleeing. Waiting for a signal from a generous kapo, Marija tends to her baby in the barracks, where “the rhythmic beaming of the floodlights that entered through a crack in the wall tore again and again, clawlike, at the darkness.” She fixates on physical cues, such as Polja’s “quiet gurgling, which was no longer communication in any earthly language but simply a slight whisper in the tongue of death itself.”

Thankfully, there is no cheap moralizing here about the child as a miracle out of the darkness. He is merely an accident (and, when he cries, a liability), one born out of a clandestine affair between Marija and Jakob, a Jewish doctor who has been pressed into the service of Dr. Nietzsche, the novel’s Mengele doppelganger. The translator’s afterword tells us that Kiš regretted calling his evil doctor Nietszsche; he considered it heavy-handed. Indeed, it is a mistake, but one that doesn’t leave the novel hamstrung. (Other small missteps appear, such as when Dr. Nietzsche uses the term “genocide,” which wasn’t formally defined until 1944 and likely would have been unknown to him. The fault may be the translator’s.)

But Dr. Nietzsche is genuinely menacing and illustrative of the perverse philosophy of Nazi eugenics. One night, he enters Jakob’s room—Marija, post-coital, ducks into the wardrobe—where he resembles a vulture circling his prey. Beginning in a roundabout, oracular manner, he eventually comes out with it: Should the Nazis lose (the Russian guns can be heard in the distance), Dr. Nietzsche wants Jakob to preserve a “collection of skulls” of Jews. Continuing, he instructs Jakob to “endeavor to prevent the destruction of these valuable collectionsthat could wind up being the only remaining evidence of your extinct race.” It’s an apt reflection of the almost science-fictional messianism underlying Nazism: Their barbarisms must be preserved for posterity.

After the war, Marija and Jakob, having survived and reunited, visit Auschwitz. Here is where Kiš shows particular prescience, anticipating the insufficiency of historical remembrance, the way that these manicured sites and their guided tours can appear unintentionally banal. They witness a boy snatch a pair of rusted glasses from a pile, put them on, and yell, “Ich bin Jude!” to the delight of his friends, before chucking the glasses back onto the pile. Later, some tourists approach the morbid curiosities that have become part of the Nazi doctors’ legacy: “a group being led by a docent stopped in front of the cases with the little malformed creatures and listened to the monotone explanation, as professional and as indifferent as could be.”

Secure with his Christian mother in Hungary, Kiš escaped the camps, but he dealt with survivors all his life. In The Lute and the Scars, the story “Jurij Golec” concerns a survivor living in Paris who, after his wife dies, asks the narrator to find him a gun so that he can commit suicide. Golec is unable to reason himself out of this decision: “I started searching for books that would give me strength to keep on living. And I arrived at the tragic conclusion that all the books I had devoured over the decades were of no use to me in that decisive hour.” As with the well-ordered Auschwitz museum, the trappings of civilization provide comfort for those who didn’t have to face the war rather than those who suffered through it.

“Jurij Golec” doubles as a requiem for the author’s friend. The story’s postscript tells us that Golec is “merely one of the names that my unfortunate friend Piotr Rawicz assigned the narrator in his one novel, Blood From the Sky.” A pitiful sadness hangs over this brief note—the use of “merely” and “unfortunate,” even the detail that it was his “one novel.” Like Golec, Rawicz was an Auschwitz survivor who committed suicide after his wife died.

“Jurij Golec” reflects the twin strands of influence and remembrance that run through Kiš’s work. Few writers have dealt so directly with their forebears as Kiš, who often made them his stories’ protagonists. He titled one of his novels Hourglass, which Aleksandar Hemon, in his introduction to a 2003 edition of Garden, Ashes, argues is an homage to Bruno Schulz’s Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. He’s likely partly correct, as a letter from his father that Kiš used in Hourglass also mentions that he’s considering writing “a bourgeois horror novel,” which he might title Hourglass.

Each of the stories in The Tomb of Boris Davidovich is dedicated to a different writer. The title story from The Lute and the Scars contains a postscript offering that it was written “under the influence of Truman Capote.” (Upon his death, Kiš left behind extensive notes about his work, including proposed tables of contents for future story collections.) “The Debt” is about a dying Ivo Andric, attempting to settle last accounts. The story is told mostly in the form of a list of brief statements that form an ersatz will—e.g., “To Ana Matkovsek, who taught me the language of flowers and herbs: two crowns.”

***

Kiš’s reverence isn’t mere name-checking. It’s rather a more obvious manifestation of his intimate relationship with the culture and history (as well as the familial legacy) on which he continually drew. And yet, the question of influence becomes thornier when considering Borges, the writer whom Kiš may most resemble. In his introduction to The Lute and the Scars, Adam Thirlwell quotes from some of Kiš’s writings on Borges, in which he praises the Argentine’s use of “documents” as “the surest way to make a story seem both convincing and true.” Poems, newspapers, books, and the like are always cropping up in Kiš’s work. But Thirlwell also mentions that Borges wasn’t translated into Serbo-Croatian until the 1970s, by which time Kiš had been publishing for a dozen or more years. And even early in his career Kiš displayed some Borgesian tics. In The Attic, for example, the author includes a chunk of dialogue, in French, from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain—the sort of technique that calls to mind Borges’ repurposing of Don Quixote.

Later in his career, when he began to publicly acknowledge Borges as a supreme figure in the history of the short story, Kiš claimed that A Tomb for Boris Davidovich was his response to A Short History of Infamy, Borges’ compendium of tales about criminals. What Kiš seemed to find in Borges, then, was an artist of similar temperament, whose example spurred Kiš to amplify some of his own tendencies.

Yet there are some important differences between the two. Both used the instrumentation of “false documents”—discovered texts, police reports, remarks from real historical personages—to further a sense of verisimilitude. Kiš also used these materials to state in fiction what could not be said in life. In Hourglass, Kiš includes a wartime letter from his father, complaining about problems with relatives and other petty matters. Ported to the realm of fiction, the letter takes on the haunting effect of its surrounding context; it resonates with the knowledge that last words are rarely planned.

And whereas Borges, a lifelong librarian, emphasized the mystery and magic of found texts, Kiš drew from a world in which they could be dangerous. In the marvelous story “The Poet,” a pensioner is arrested for posting a poem critical of Tito. (It’s just after the end of the war.) Rain has destroyed the poem, so the pensioner is forced to recreate the poem from memory. Except he can’t remember it, so his interrogators make him write a new poem, rewriting it again and again, continually “improving” it until they are satisfied. The story combines the absurdism of communist totalitarianism (Brodsky’s jailers also asked him who gave him the authority to write poetry) with the fascist mania for evidence and precision. It also literalizes the philosophical notion of art as a vehicle for personal liberation.

“The documents we use speak the terrible language of facts,” Kiš writes in “The Knife With the Rosewood Handle,” “and in them the word ‘soul’ has the sound of sacrilege.” Kiš came of age in a time when documents could send someone—a father, say—to his death. To make them the heart of his fiction was both a capitulation and an act of reclamation. He may have had in mind the original Psalm 44, which asks why God abandoned his people, who kept the “covenant,” that ultimate document of faith.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jacob Silverman is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and book critic. He is also a contributing editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Jacob Silverman is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and book critic. He is also a contributing editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review.