In a Birch Forest, With the KGB

Extraordinary photographs of a refusenik picnic in 1974, when Soviet Jews were far from free

Civil rights was part of my background for as long as I can remember. I took personally, the biblical command “Justice, justice you shall pursue,” emphasizing the Hebrew “you” in the singular which, in my view, requires everyone to act. As a student at Harvard Law School, I witnessed great civil libertarians from the classroom to the courtroom in the cause of individual liberty. Upon graduation, I joined them as a lawyer in the military, then, on behalf of the U.S. government, I lectured on civil rights throughout the world. I was also president of the American Civil Liberties Union in Philadelphia. We brought up our children speaking Hebrew and I was president of their Hebrew day school.

All that motivated our responding to the call when, in 1974, the Philadelphia Bar Association organized the first trip of lawyers directly from Philadelphia to the Soviet Union on Aeroflot airlines. It was designed as a friendship trip for lawyers and judges to meet our counterparts in Moscow and Leningrad.

My wife, Shulamith, and I loaded up with jeans, records, books and whatever else would sell in the Soviet Union to support refuseniks, who had been thrown out of work for applying for an exit visa to Israel. We brought Hebrew books which were banned in the USSR. As a professor of constitutional law, I brought my notes, which included a quotation from Lenin that speech against the government should not be permitted.

From our hotel in Moscow, we took whatever we could carry and walked to 15 Gorky Street, the apartment of Vladimir and Masha Slepak, the center of the Soviet Jewry movement in Moscow.

Assembled there were refuseniks eager to seek our help. As a lawyer and law professor, I was asked to bring up their plight with Soviet lawyers and judges at public meetings planned by our tour. One of the most egregious cases dealt with a Jewish doctor named Mikhail Stern accused of poisoning non-Jewish children, a well-known canard dating from the Middle Ages. Among those in the Slepak apartment was Anatoly Sharansky whose prosecution by Soviet authorities was yet to burst upon the international scene.

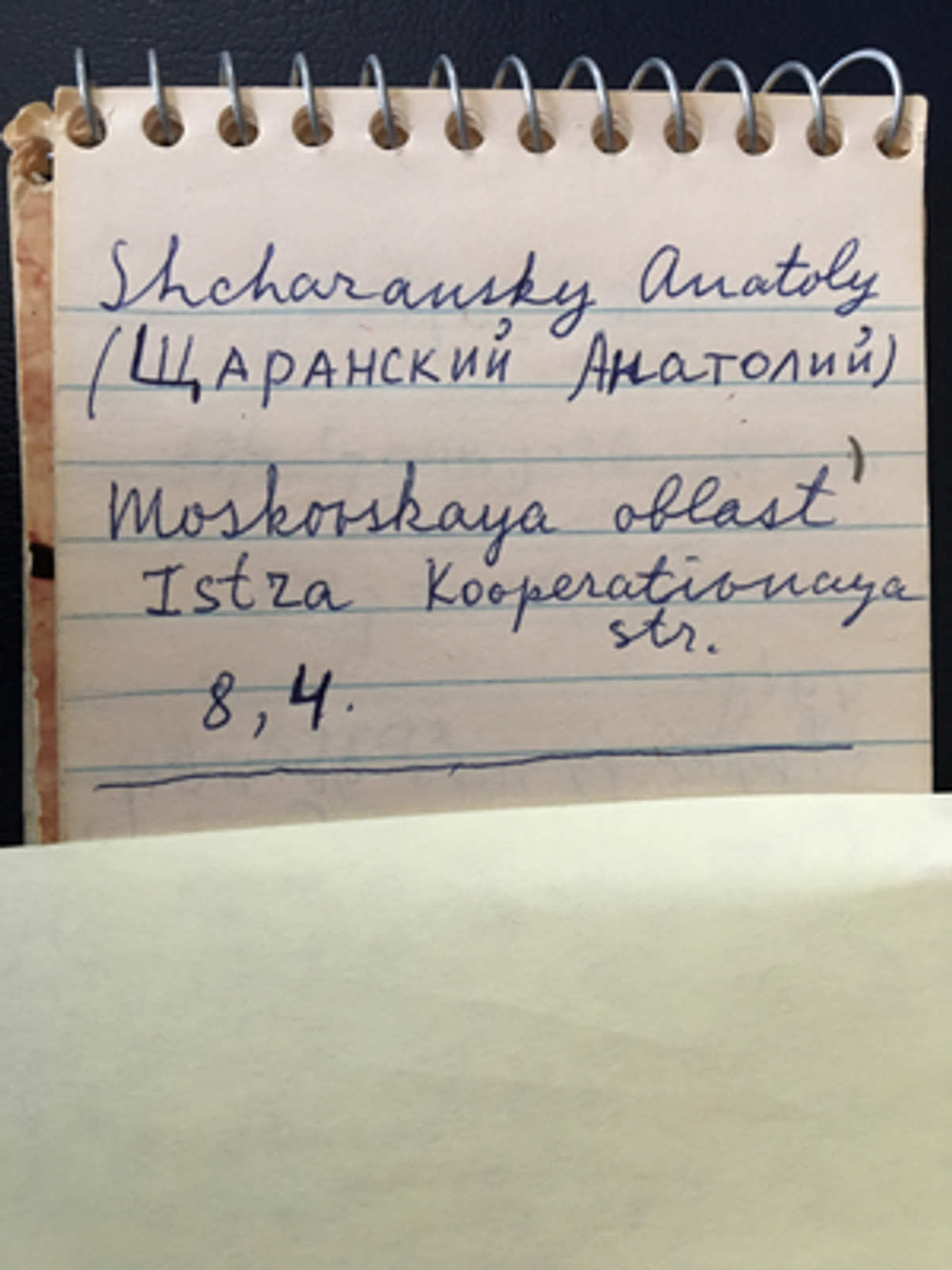

For purposes of recording information and requests of refuseniks, Shulamith brought a pocket-size notebook for me with a dour orangutan on the cover, in the hopes that the Soviet police would decide that whatever was inside wasn’t serious. I wrote notes in Hebrew, which I hoped that the Soviet police would not know. Refuseniks wrote mainly in Russian, which I had learned to read for the purpose of recording their information. Some wrote in English. More than halfway through my notebook appears the name “Shcharansky Anatoly” and his address, which he wrote in Russian and English.

I hardly spoke to Sharansky that evening, since his name was not among those given to us when we were briefed in Philadelphia for our trip. We were told that the most important refuseniks were Vladimir Slepak and Alec Goldfarb, who spoke fluent English and were the main contacts with the Western press. Their reporting on the Soviet Jewry movement was essential to warn the Kremlin that their every violation of human rights, and even Russian law, was reported in detail throughout the world. I was to focus on pending trials and urgent requests of refuseniks.

When Goldfarb was released, he wrote to us from Israel that he was succeeded in the Soviet Jewry movement in Moscow by Dina Beilina and Anatoly Scharansky (his spelling) in contacts with the Western press, and that we should do for them what we did for him, specifically, urge the Western press to publicize their names and other refuseniks in immediate danger of Soviet punishment. Goldfarb added that Scharansky had a wife in Israel, Avital, who was granted an exit visa upon their wedding, while her husband was denied. That initiated decades of joint effort between us, in addition to many others the world over.

***

On our first evening in the Soviet Union, refuseniks at the Slepak apartment emphasized that as an American lawyer and professor of law, my message was bound to be taken seriously by Russian judges. Alexander “Sasha” Luntz, a prominent intellectual and mathematician, was insistent that public denunciation from me would save Dr. Stern from the charge of poisoning Russian children.

Luntz was the son of the Soviet lawyer who brought suit in France and won for the Soviet Union the return of the Romanoff jewels. He was a close friend of Sharansky, and prided himself on being steeped in classic Russian literature and culture. He had the additional distinction of tracing his heritage to Rashi, the 10th-century French-Jewish commentator on the Hebrew Bible.

We were invited to attend a picnic by the Slepaks, Goldfarb, and Sasha Luntz, our new-found refusenik friends, to celebrate the holiday of Sukkot, which commemorates 40 years of wandering in the desert by the Children of Israel after their exodus from slavery in Egypt.

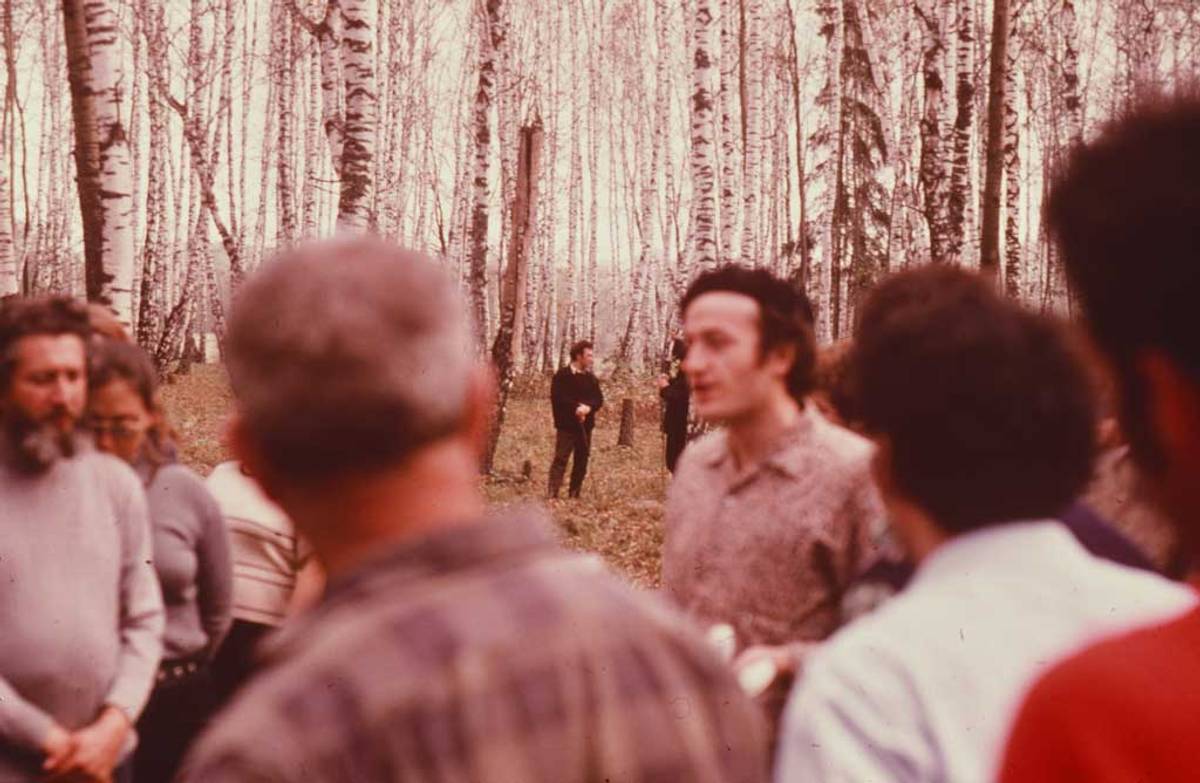

By Metro, bus, and a mile hike over streams and rough fields, we came to a birch forest where about 75 to 100 people had assembled. A makeshift table of logs was set up and spread with holiday treats. Men and boys played soccer in a clearing in the woods and children romped with abandon. We were greeted with hugs and kisses.

My photographs of the picnic in the birch forest appear in the slideshow below.

Soon all gathered for the holiday prayer. I was handed a small Israeli siddur, or prayer book, by Luntz and asked to chant the Kiddush, the traditional Hebrew prayer, for the holiday of Sukkot. Only after we returned home and my photos were developed, did we notice that in two of my pictures, Anatoly Sharansky was included. You can see him wearing a cap and gray sweater.

Suddenly, the mood changed. A hush fell over the crowd and all frivolity stopped. The soccer game ended, and children ran to the nearest adult. We were stunned. What was happening?

The answer was immediate: The KGB had arrived, albeit disguised as peasants, wearing rough boots and carrying huge sticks. They pounded the ground, pretending to search for mushrooms.

Of course, their purpose was to instill fear. On previous occasions they had severely beaten refuseniks and at least one in our group that day still hobbled from a broken leg previously inflicted by KGB thugs.

Immediately, the siddur was taken from me and handed to Eliahu Essas, a student expelled from the Moscow synagogue yeshiva when he applied for an exit visa to Israel. He chanted the prayer in Hebrew with translation into Russian to prevent the accusation that he was making an unlawful speech.

I moved away quickly and raised my camera as inconspicuously as possible to take a picture of the menacing KGB, but I was stopped by the refuseniks who were terrified that we would all be arrested and beaten in the process. So, I aimed my camera to give the impression that I was focusing on Essas, not the KGB several meters away. In reality, I did the opposite, with the KGB in focus in the background.

Essas finished chanting the Kiddush. The picnic was over.

We left, walking past hostile stares, singing Hebrew songs proudly, bolstered by the bravery of our fellow Jews and fortified by the words of the biblical prophet Micah, “V-ain machreed,” “And none shall make them afraid.”

Three years later, in the frigid December of 1977, I returned to Moscow on behalf of Anatoly Sharansky, who had been imprisoned on the charge of espionage for the United States, a crime punishable by death. President Jimmy Carter denounced the charge as patently false. Academics who knew Sharansky rallied support for him.

I persuaded Temple Law School Dean and recognized international law scholar Peter Liacouras to come with me to Russia to aid Sharansky and specifically to persuade the prosecutors that the imprisonment of Sharansky violated Soviet law as well as international law.

In Moscow, we arranged to meet with officials of the Moscow Bar who were in effect officials of the KGB. In addition to legal arguments, we offered to establish a summer program in Moscow on the model of Temple Law School programs in other countries financed from the United States. This whetted the Russians’ appetite for American cash, but we conditioned our offer on Sharansky’s release. We cited the Russian Criminal Code which we brought with us from the Temple Law Library, to prove that his imprisonment violated the law of the USSR. We stressed that the Temple Law faculty would not tolerate such injustice!

Their snickering response was, “in a few months none will remember the name Sharansky!”

Anatoly Sharansky was released from the Soviet Union by walking across a bridge in Berlin from the Russian to the American zone. Ordered by the Russians to walk straight across the bridge in Berlin to the American forces on the other side, he walked in a zigzag pattern to freedom.

Sharansky soon came to Washington to meet President Ronald Reagan. Shulamith and I, together with Alexander “Sasha” Luntz, recently liberated Soviet Jewish refusenik who was staying at our house, went to the nation’s capital to meet Sharansky before he saw President Reagan. I started to remind Sharansky who we were, as it was many years since we last met in Moscow. He stopped us at once and said that he saw us every day of his imprisonment because a photograph of Shulamith and me together with his wife, Avital, was taken by our son, Gidon, in Jerusalem, and smuggled into his cell in Moscow. Because of the photo, Anatoly told us, he greeted us every day.

***

On this day, Feb. 11, in 1986, Natan Sharansky arrived in Israel for the first time. The Power of Protest: The Movement to Free Soviet Jews, highlighting stories of everyday Americans who performed extraordinary acts of bravery to help Soviet Jews, is on view at the National Museum of American Jewish History through March 15. Natan Sharansky, his daughter Rachel, Malcolm Hoenlein, and Elan Carr will discuss “How the Soviet Jewry movement can influence and inspire the movement to combat anti-Semitism” on March 15 at the National Museum of American Jewish History, the day of Sharansky’s arrest by the KGB.

Burton Caine is professor of law at Temple University and former president of the Philadelphia chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Burton Caine is professor of law at Temple University and former president of the Philadelphia chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.