Should We Love Our Country?

Fourth of July ruminations on the nation-state and the state of the nation

This week is the 4th of July, and should we love our country? Richard Blanco was President Barack Obama’s inaugural poet in 2013, and, although I do not claim to be a Richard Blanco fan—his sappiness is not my sappiness—I do admire the title of his new poetry collection, How to Love a Country, for putting the question so directly. And I admire his answer. He presents it in his introductory poem, “Declaration of Inter-Dependence,” which amounts to something of a 4th of July oration. Poetry rests on the principle that rhythm is reason, and Blanco in his “Declaration of Inter-Dependence” jams two rhythms against each other—a calm legal rhythm from Jefferson’s Declaration, and, then again, a propulsive rhythm of quotidian ordinariness—in order to conjure a suitably disjointed reality:

Such has been the patient sufferance …

We’re a mother’s bread, instant potatoes, milk at a checkout line. We’re her three children pleading for bubble gum and their father. We’re the three minutes she steals to page through a tabloid, needing to believe even stars’ lives are as joyful and bruised.

Our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury …

We’re her second job serving an executive absorbed in his Wall Street Journal at a sidewalk café shadowed by skyscrapers. We’re the shadows of the fortune he won and the family he lost. We’re his loss and the lost. We’re a father in a coal town who can’t mine a life anymore because too much and too little has happened, for too long.

—and so on, with austere textual quotations juxtaposed to messy circumstances.

He arrives at this:

We hold these truths to be self-evident…

We’re the cure for hatred caused by despair. We’re the good morning of a bus driver who remembers our name—

And the sappiness does him in. It leads him to look for ways to clear up the rhythmic jumble. But what if the jumble cannot, in fact, be cleared up, and the sacred American texts and the secular American realities are hopelessly in conflict, like a marching band with two sets of drummers?

Jill Lepore, the historian, has published her own version of How to Love a Country, under the title This America: The Case for the Nation, except that, instead of wondering how to love a country poetically, she wonders philosophically and historically. She argues that nation-states are good things, practically speaking, which means that emotions in favor of a nation-state ought to be a good thing, as well. We should love our country. But there is more than one way of doing so.

She quotes Donald Trump (whose presence hovers unnamed and abominated over Richard Blanco’s poems, as well), who claims nationalism for himself. And she responds by saying that, in that case, nationalism is not for her. Patriotism seems to her a better and more affable idea. “Patriotism is animated by love, nationalism by hatred.” Then again, she relents on nationalism after a while, and, with a glance at the American past, she sets about drawing a series of nuanced distinctions: between bad nationalism and good nationalism, which does seem to exist; between illiberal nationalism and liberal nationalism; between the Confederate nationalism of the Civil War and the nationalism of the Union. She mentions the nationalism of Herman Melville, with a suggestion that here was a good nationalism, except that it veered into imperialism and thereby revealed a dangerous propensity for things to morph. She finds herself acknowledging that Yael Tamir of Israel has a point, and maybe the liberal tradition and the national tradition can, in fact, accommodate each other; and, then again, finds herself supposing that Tony Judt had a point, as well, and liberal nationalism ought never to have been invented in the first place. But we are stuck with it. And, in this fashion, by carving one sharp distinction after another, she finally blunts her knife and leaves me wondering if she has said anything at all on the topic of American nationalism. Perhaps she has merely looked for ways not to appear guilty of ideological crime.

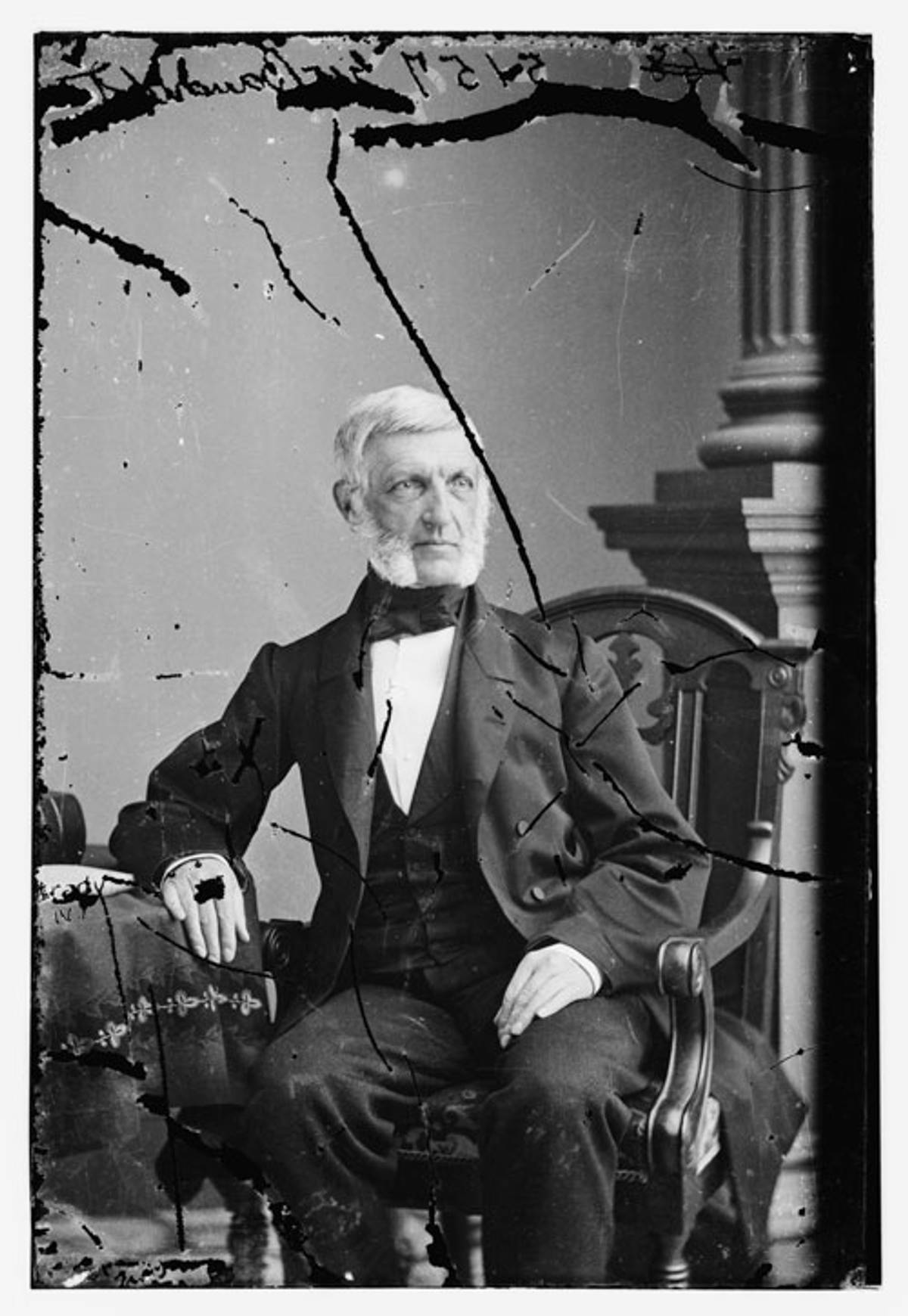

I admire her method of argument, though. It is Richard Blanco’s. It is a piling up of historical texts, in juxtaposition with social realities. One of her historical texts turns out to be a favorite of mine, which fills me with delight. It is by George Bancroft, the historian. Bancroft was the Michelet of America, except that America tends to neglect its literary gods and ancestors, and not even the Library of America includes Bancroft in its library. His masterwork was a History of the United States, the first volume of which came out in 1834, during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, followed by I don’t know how many additional volumes during the next few decades. My own edition, which I bought on the internet—it is a bad habit, I have got to shake it, I’ll go broke—came out in 1858 and includes seven of the volumes, which brings me only to the year 1775 and the Battle of Bunker Hill. I will concede that History of the United States by George Bancroft is not the liveliest multitome immensity ever written.

There is a grandeur in his history, though. Bancroft was a Massachusetts man who attended the lectures of Hegel in Germany. And, as anyone might do who had undergone such an experience, he looked upon all of history as a single forward-rushing development through the eons, subsuming the whole of human activity, not to mention the activity, such as it is, of the rocks and the plants and the animals, leading to (in small caps, in order to emphasize the more than worldly nature of the phenomenon) ꜰʀᴇᴇᴅᴏᴍ. And he saw a glorious role for the United States in all of this, which was a worldwide role. Hegel entertained the same notion about America and its universal destiny. He uttered cryptic remarks in that direction. This makes Jill Lepore a little nervous.

The nationality was created by explorers and immigrants and refugees, who, in streaming hitherward from other parts of the world, mingled their energies, instead of remaining separate from one another.

She quotes from an oration of Bancroft’s from 1854, which was published under the modest title The Necessity, the Reality, and the Promise of the Progress of the Human Race—and what a fine geyser of the 19th-century imagination that turns out to be! Mighty rivers of philosophical truth and beauty flow serenely by, beneath a mountain range of Christian doctrine. The atheist proclivities of modern thought amble past, only to be shot down with a blast of the rifle. The cosmos was Bancroft’s theme. If he was a nationalist, his nationalism was expansive in the extreme, such that even something as large as the United States, having already crept across the continent, appeared almost small, as if seen from the moon.

And yet, tiny as it was, America in his eyes exercised vast and benign influences on world events in every direction—eastward, by rejuvenating the exhausted old nations of Europe; westward, by offering a model of ꜰʀᴇᴇᴅᴏᴍ to the outstretched hands of the still older nations of Asia. Bancroft was the grand philosopher of what has come to be called, in our own time, American exceptionalism, except that, instead of ascribing America’s worldwide liberating role to God in a supernatural fashion (which is how all of the critics and some of the defenders of American exceptionalism picture the doctrine), he took the trouble, in The Necessity, the Reality, etc., as in his History, to postulate nonsupernatural reasons for America’s unique place in world affairs. The chief among those reasons was a matter of the American nationality, or national character.

Lepore makes the argument that other countries are nation-states because first they were a nation, and then they organized a state, whereas the United States is a state-nation. First came the state, and then the American nationality. But Bancroft saw an American nationality or cultural identity that antedated the state. The nationality was a miracle of hybridization. The Revolution and the republic, when they arose, were its result and not its cause. The nationality was created by explorers and immigrants and refugees, who, in streaming hitherward from other parts of the world, mingled their energies, instead of remaining separate from one another. And, in doing so, they created the first truly cosmopolitan or universal culture, or, at least, the first since Roman times. America’s nationality was a “nationality of nations,” as the Jacksonians liked to say. Or, as we moderns might say, it was a flower of the multicultural. And it spoke to the nations, as no other nationality could do.

Lepore offers a marvelous quotation on this theme from Bancroft’s The Necessity, the Reality, etc., but here is a slightly larger excerpt. Bancroft said:

Our land is not more the recipient of the men of all countries than their ideas. Annihilate the past of any one leading nation of the world, and our destiny would have been changed.

In cadences a poet would admire, he let loose:

Italy and Spain, in the persons of COLUMBUS and ISABELLA, joined together for the great discovery that opened America for emigration and commerce; France contributed to its independence; the search for the origin of the language we speak carries us to India; our religion is from Palestine; of the hymns sung in our churches, some were first heard in Italy, some in the deserts of Arabia, some on the banks of the Euphrates; our arts come from Greece, our jurisprudence from Rome; our maritime code from Russia; England taught us the system of representative government; the noble Republic of the United Provinces bequeathed to us, in the world of thought, the great idea of the toleration of all opinions; in the world of action, the prolific principle of the federal union. Our country stands, therefore, more than any other, as the realisation of the unity of the race—

—with “the race” meaning the human race, and its unity leading, as he insisted, to ꜰʀᴇᴇᴅᴏᴍ.

Isn’t that wonderful? Isn’t that a fine expression of our modern liberal idea? It is not an ethnic swagger, it is a multiethnic swagger.

Lepore is not convinced. Bancroft, she says, “wrote the history of the United States as the history of the providential founding of the world’s first modern democracy by the ‘white man,’ after his conquest over ‘savages.’ Bancroft believed that slavery was a national sin and warned that it would doom the Republic; he blamed Africans: ‘negro slavery is not an invention of the white man.’ Bancroft’s universalism was no univeralism at all.”

Actually, he blamed the British, too (in Volume 7 of my 1858 History of the United States). He was catholic in his aspersions. He also had a flair for saying things like this, in The Necessity, the Reality, etc.:

The good time is coming, when humanity will recognize all members of its family as alike entitled to its care; when the heartless jargon of overproduction in the midst of want will end in a better system of distribution; when man will dwell with man as with his brother; when political institutions will rest on a basis of equality and freedom.

To be a champion of multiculturalism and, at the same time, a friend of the working class was not at all impossible. In my reading of him, nothing in his fundamental standpoint should have prevented him from adding that Africa, too, contributed to the United States, as more than obviously it did, and likewise the Indians of America, and not just of India.

Why did he shrink from adding those points, then? What quality was missing in George Bancroft? It was the political courage to stand up to the Southern reactionaries. Northern cowardice was his failing. By the time he delivered his oration on The Necessity, the Reality, etc., he was a Franklin Pierce man, who gazed boldly outward and offered revolutionary solidarity to the embattled European democrats; and, in other respects, lowered his eyes in shame, lest the African Americans or their friends might be watching. Bancroft’s universalism was a universalism, in my opinion. But it was a deformed thing, as if some deranged Southerner had hacked off part of his nose.

Here, then, is our present-day debate about America and its past. Was America a giant falsehood in the past, a universalism that was no universalism at all, as shown by the ways in which Americans of the past, except maybe a handful, failed to conform to the superior understandings of our own enlightened time—a falsehood that cannot really inspire love, except by twisting ourselves in knots? Or was America in the past a giant truth, whose flower has needed a few centuries to blossom, and is not yet in full and fragrant bloom, and may require several more centuries of watering and sunlight—which is the sort of idea that Bancroft might have contemplated as he dozed on his lecture-hall bench, listening to professor Hegel natter on about “Die Knospe verschwindet im Hervorbrechen” and the philosophy of history, and so forth.

Only fanatics look for definitive answers to these questions. Jill Lepore argues with herself by running her eye across the centuries, and Richard Blanco argues with himself by ruminating over his own circumstances, and the arguing is to her credit, and his. Isn’t this how we ought to spend the 4th of July—a moment for drum-and-bugle parades and vexed reflections at the same time, the one affirming the other?

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.