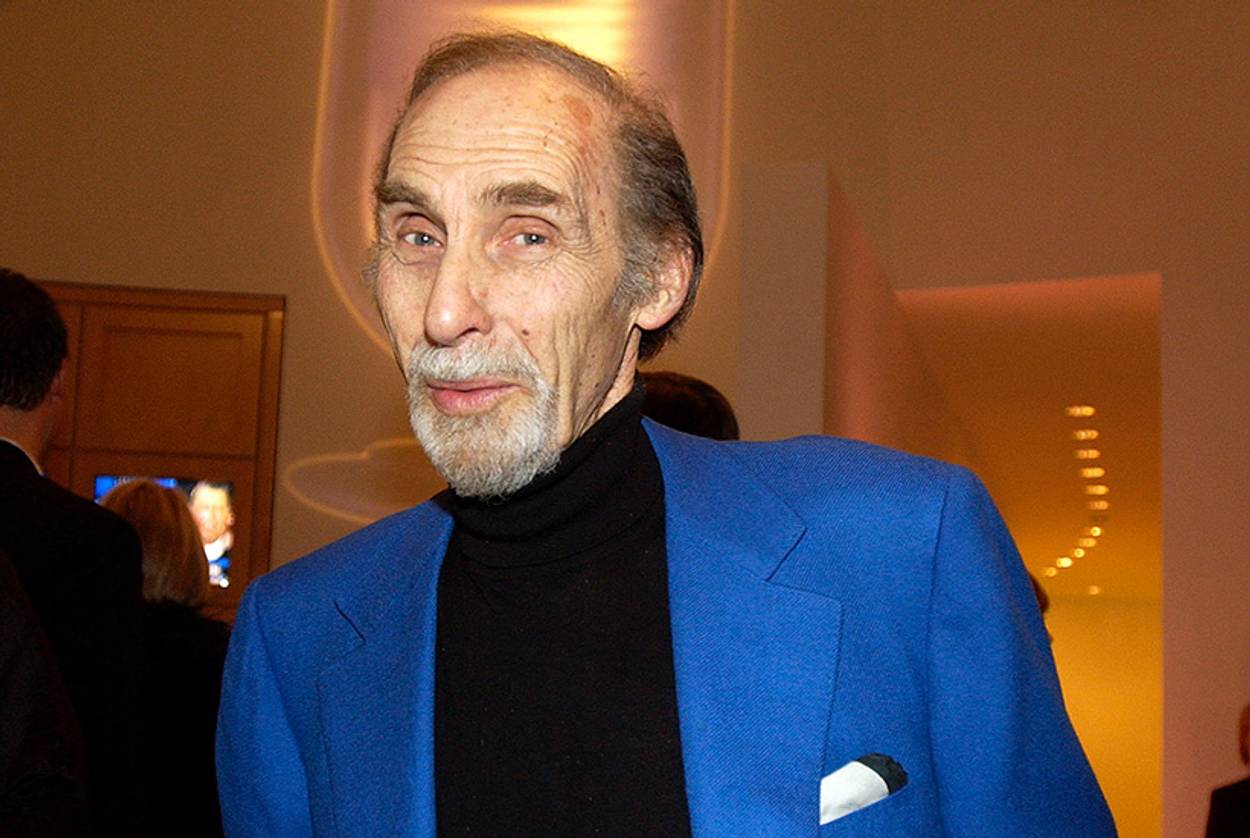

The Deep Jewish Roots of Television’s Caesar

The late, great comedian’s ‘Your Show of Shows’ tried to pass in postwar, assimilationist America

There was nothing conspicuously Jewish about Your Show of Shows. There were no Jewish jokes or Jewish characters, as there were, say, on The Goldbergs (at least the original Goldbergs). Only occasionally did some Yiddish word slip in, and it was always well-camouflaged, either appearing as pidgin-German or tossed off sotto voce in some rapid-fire dialog.

Of all the languages Sid Caesar imitated, Hebrew most certainly wasn’t one. Not once in its four-year run were words like “Jew” and “Jewish” ever uttered. The State of Israel, newly born, went unmentioned. Caesar and his colleagues saved their Jewish material for private moments, far off camera. America never got to hear Caesar’s imitation of a Jewish labor leader riding the subway to a strike. When Carl Reiner interviewed Mel Brooks’ 2000-Year-Old Man, it was strictly at parties, for friends.

But a point predictably omitted from all the tributes to Caesar, who died Wednesday at the age of 91, is the fundamental Jewishness of his work. At its core, nearly everything about Your Show of Shows, the seminal program on which Caesar shined from 1950 to 1954, was Jewish, including its very desire not to look that way.

The personnel, of course, were Jewish. The producer, the Viennese-born Max Liebman, was a Jew. So, too, with one late exception (Tony Webster, an Irish Catholic), were all of its writers. That included its first two, Mel Tolkin (born in the Ukraine) and Lucille Kallen, and extended to Mel Brooks, the Simon brothers (Neil and Danny) and Joe Stein. So, too, were three of its four stars: Caesar himself, along with Carl Reiner and Howard Morris.

And so was much of its audience. In its early days, television was largely an East Coast, urban phenomenon. That meant, to a significant extent, New Yorkers, sophisticated New Yorkers, which meant Jews. Saying you watched Your Show of Shows was a way to kvell. Jews elsewhere embraced it as the work of landsmen. When Tolkin, the head writer, wanted to get his wayward troops in line, he knew what to say. “Gentlemen, we’ve got to get something done!” he would declare. “Jews all over America will be watching Saturday night!”

Its themes were Jewish. It was, for instance, forever poking holes in stuffed shirts. In many of its sketches, the pompous look ridiculous or get their comeuppance. Tight-assed, aristocratic Englishmen mumbling unintelligibly were a regular target. So were the kinds of pretentious salons where, were its humor coarser, a Margaret Dumont might have appeared. One classic sketch has Caesar, in tie and tails, disrupting a snooty musical recital—one Miss Rose Weed singing “Lo, Hear the Gentle Lark”—by coming in late, treading noisily, cracking his knuckles, winding his watch, fidgeting on his chair, realigning his nose, writing in his notebook, rattling his brains, and getting his finger caught in a cigarette case.

Many of the show’s most famous, and memorable, sketches revolve around another predominant Jewish theme: food. (Everyone has to eat, so what is it that makes Jews uniquely obsessed with it?) Always underlying these routines is anxiety: that, somehow, one is not going to get enough to eat, or that some waiter is blowing him off, or that the food is taking too long to come, or that, as in one of the best sketches (a lunchtime meeting set in a corporate boardroom) everyone gets his sandwich but Caesar, who sits there in agony, transfixed by someone else’s pickle.

Worst of all is being served something one can’t eat. Two decades before Woody Allen struggled through his “mashed yeast” with Annie Hall off Sunset, Caesar, at the urging of his hectoring wife, attempts to get down flowers served as hors d’oeuvres at a health-food restaurant in New York. What he really craves, of course, is a steak—or just about anything else—at his favorite Italian dive. “Look, Doris, I don’t want to eat here,” he complains. “I mean, let’s not experiment, eh? I’m hungry now. Look, why don’t we go to Pepito’s? We can get those nice spiced snails, you know, and we can get those hot tamales with the red sauce, and then we can have some more snails, and then we can have some pickles with the hot mustard, and then we can have the spiced sausages, you know? After all, why take chances with your stomach?” Then as now, for Jews a meal is a terrible thing to waste.

Your Show of Shows was Jewish in its worldliness—prime evidence of what the Soviets once labeled, in their classic anti-Semitic code, “cosmopolitanism.” It was surely the only show in television history to regularly spoof foreign movies: Italian, French, Japanese, German. Caesar, Reiner, Brooks, and the others would watch them at the Museum of Modern Art, then walk up to the writers’ room a few blocks north to take them apart.

It’s also Jewish in its peculiar sensitivity to Jewish pain. Two of Caesar’s most famous characters were German. It makes sense: It was the one language he and his Jewish co-stars, steeped in mamaloshen, could easily imitate. (And which, for all her talents, the very un-Jewish Imogene Coca could not.) But one of those characters, the buffoonish German professor, was timeless. And the other, the imperious German general (he appears in many sketches; in the most famous, barking out orders to the valet who dresses him, he turns out to be a doorman) was always from WWI, not II. Six or seven years after the Holocaust, it was still “too soon.”

And it was Jewish in its pretentiousness. Max Liebman wanted an elevated show. It’s why he all but banned Yiddish from the program; not for him the low shtick of Milton Berle, who might crown his ditzy secretary “Miss Shugana of 1953.” It’s also why he filled it with stars from the Metropolitan Opera and imported classy guest hosts like Rex Harrison and Basil Rathbone rather than more vulgar types from vaudeville or Tin Pan Alley. An early misadventure with the cartoonist Al Capp, who strayed off script to mention H-bombs—a taboo for a program that frowned on topicality, much less controversy—may have curbed further experiments with edgy Jews.

Much of Your Show of Shows wasn’t comedy at all, but song-and-dance numbers dripping with nostalgia, recalling an America of calliopes and band shells that had little to do with Jews. Its domestic sketches featured Caesar and Coca as Charlie and Doris Hickenlooper, an ethnic-free couple whose last name was lifted from a senator from Iowa. (True, sensitive Jewish viewers might have regarded theirs as television’s first intermarriage. Charlie is the Jewish father, beside himself over his baby’s mild fever, donning a mask and gloves to give him an aspirin, while Doris is the gentile wife, completely unperturbed. “I never saw such carrying-on in my entire life,” she complains.)

In its own half-hearted and endearingly unconvincing way, then, Your Show of Shows tried to pass. In postwar, assimilationist America, what could have been more Jewish?

***

Like this article? Sign up for ourDaily Digestto get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David Margolick, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, is writing a book for Nextbook on Your Show of Shows. He’d appreciate hearing from those with memories or comments on the program: [email protected].

David Margolick, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, is writing a book for Nextbook on Your Show of Shows. He’d appreciate hearing from those with memories or comments on the program: [email protected].