Back in 1983, the comic-book artist and writer Howard Chaykin scripted the following exchange into issue No. 2 of American Flagg!, his series about a chiselled, heroic supercop named Reuben Flagg. A woman sidles up to Flagg and says:

“Can I ask you just two questions?”

“Shoot!”

“Are you really Jewish…?”

“Yes. Second question?”

“Do you want to go to the ladies room with me?”

One semi-tasteful panel later (“Wait’ll I tell Miriam and Roselee about this!”) Flagg’s back to fighting crime, as though the whole bathroom tryst, and the whole revelation that our square-jawed action hero is Jewish, never happened. And this contradicts one of mainstream comics’ most basic rules: every deviation from the norm must be both profound and consequential; if a character is Israeli (say, Marvel Comics’ Sabra), Israeliness should suffuse her every utterance; and if a character is disclosed to be, say, Jewish, the consequences of that disclosure should shape the entire story. Otherwise, why mention it at all? What’s strange about this passage, and American Flagg! as a whole, isn’t that Flagg’s Jewish; it’s that Flagg happens to be Jewish.

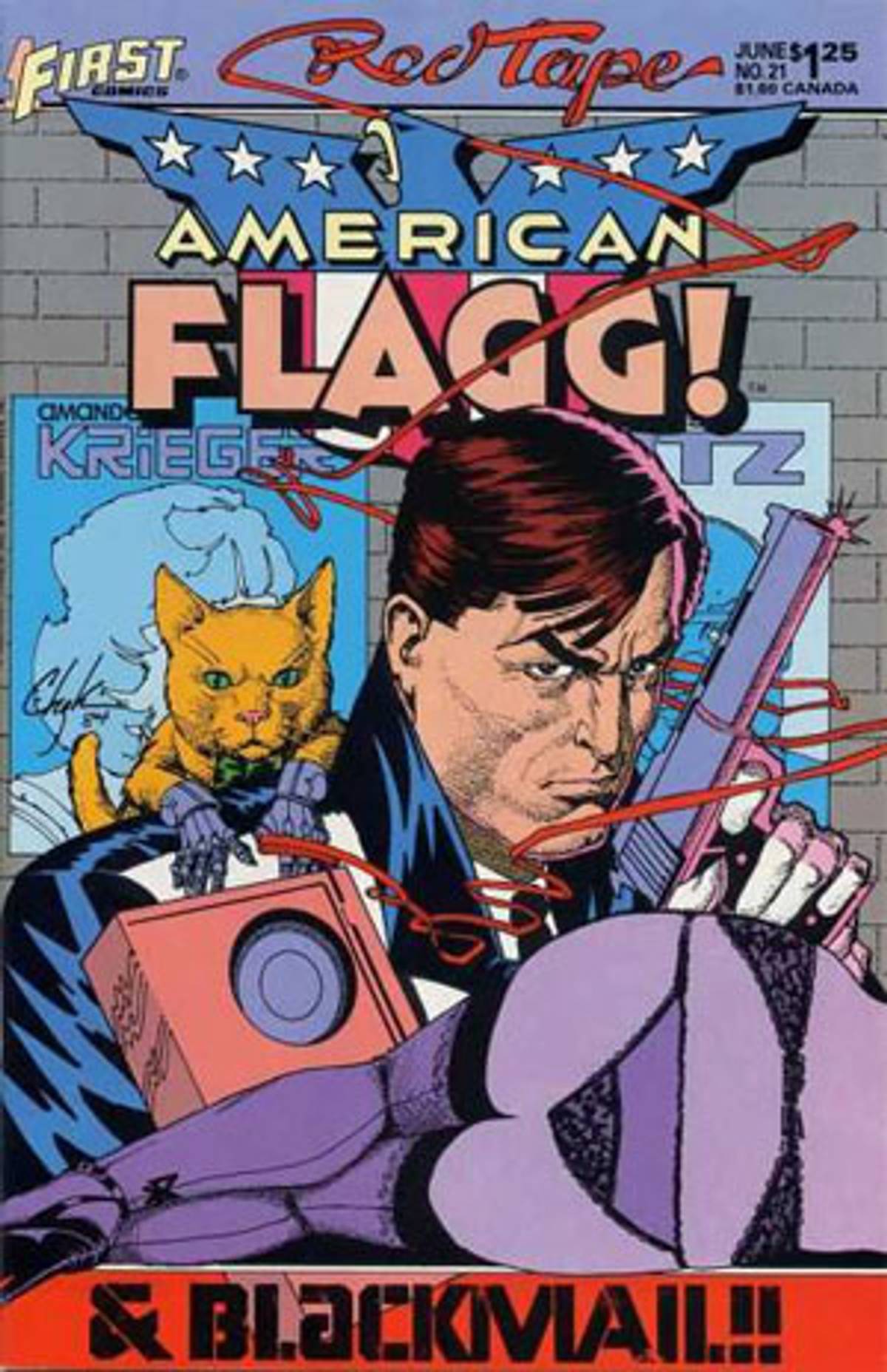

After being out of print for a decade, issues 1 to 14 of American Flagg! were finally reissued last year, in a 25th-anniversary “Definitive Edition” by Dynamic Forces, with an introduction by Michael Chabon. (The series was originally published by now-defunct First Comics.) By marrying the testosterone-fueled visuals of superhero comics to the nagging self-doubt of alternative comics (that is, everything from Krazy Kat to 8-Ball), American Flagg! managed to scale heights of vulgarity and hipness never before seen in mainstream comics.

The two great comic-book monoliths of the past 25 years—Allan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns—were inspired by Chaykin’s innovations in plotting, layout, and subject matter, although they didn’t manage to catch Chaykin’s subtler innovations in both tone and the depiction of city life. Chaykin’s best work is characterized by dialogue that reads like Mickey Spillane crossed with Noël Coward, and a cacophonous vision of urban identity that includes Martians, Brazilians, Russians, the undead, white humans, black humans, gay humans, vampires, demons, trannies, robots, and a leading man who always looks like William Holden, and almost always just happens to be Jewish.

American Flagg! is riddled with such incidentals and incidents—there just happens to be a talking cat named Raul; Ranger Flagg’s new deputy just happens to be an animatronic robot named Luther whose face looks like Reggie from Archie Comics; no one in Flagg’s world really notices or cares. Flagg—we learn in passing that his parents were Russian-Jewish “bohemians” (his middle name is Mikhail), and that he was born in Earth’s colony on Mars—just happens to bring home the luscious Dr. Titania Weiss on New Year’s Eve, only to discover she’s wearing an enormous swastika pendant under her blouse. In an X-Men comic, such a revelation would launch a solemn, main-theme-clarifying, highly rhetorical exchange between the characters. Instead, Weiss asks cheerfully, “Why mix politics and sex?” and Flagg, after hesitating a moment, turns around, rips the pendant off her neck (“Ow! That’s one way to deal with it! All right!”), and sleeps with her anyway. One cutaway panel later, we’re treated to the following half-naked exchange:

“I’m sorry.”

“For what? It was incredible. You’re an animal.”

“That was just anger, fired by self-loathing.”

And then they’re interrupted by the talking cat.

The Weiss incident has some carryover—in the next issue the cat asks Flagg why he’s been so weird the past few days, and he answers, “Let’s just say I’m not used to finding National Socialists in my bed and leave it at that”—but not enough to qualify it as a plot thread. And again, we haven’t actually seen Flagg “acting weird”; the cat just happens to mention it. This is what makes American Flagg! so difficult to read: although there is a central, action-based plotline—something about weather satellites, militias, a corporate takeover of America—it receives no more airtime than the Titania Weisses, the talking cats, or the recipe for Flagg’s spaghetti frittata.

In Chabon’s perceptive introduction to the reissue, he writes that, whereas Moore and Miller simply described 21st-century dystopias, “Chaykin went and built one.” Chabon is referring to Flagg!’s panel layouts, animated sound effects, crawls, and background visual noise. But this sense of overwhelming, unfocused detail may not be so much postmodern as simply urban. Speaking of Flagg!’s follow-up, Time², Chaykin, who grew up poor in Brooklyn, said: “I lived in a neighborhood that was Italian, Jewish, Puerto Rican, and black. You’d walk down the street and the radios were blasting from open apartment windows. It was like turning the dial of the radio. That was the inspiration for the way the dialogue reads, breaking out and opening up from different perspectives. You heard Symphony Sid on WJZ, you’d hear the Yiddish radio station, you’d hear the Latino stuff, you’d hear Daddy Divine, I loved that.”

More focused than Flagg! both in scale and scope, Time² allows us to see the logic of Flagg!’s take on Jewish identity more clearly. Whereas Flagg! casts its net from Brazil to Chicago to Mars, the two-issue Time² takes place entirely within a five-block radius, an interdimensional nexus populated by humans, robots who look like humans, and undead who look like humans. It’s an idealized, clangorous vision of bebop-era Times Square, complete with its own jazz clubs, anti-defamation leagues, and jive-talking hustlers. Its chief villain is a broker of demons named Aunt Rose daSilva who looks like Bella Abzug and is also—you guessed it—Jewish. In this case, religious and ethnic identity are more grounded in the narrative—daSilva operates out of what seems to be the Carnegie Deli, her two kids are named Dani and Azrael, her approach is always signalled by ominous—and beautiful—tendrils of Hebrew. But you still have to ask: if she’s Jewish, why does her name just happen to be daSilva?

And in such a stupid question, I think you get to the core of Chaykin’s specifically urban vision of race, religion, and ethnicity. It’s a vision conditioned by growing up in a city so multicultural that not only does difference cease to be an event; it ceases to be legible. Demons who look like humans, Jewish witches with Italian last names, robots who are actually black men, trannies who are actually vampires (who are actually porn stars)—all coexisting in a single city where a shared morphology allows everyone to pass without sacrificing their own convictions or sense of identity. In such a city—Time²‘s New York, or American Flagg!’s Plexmall—villains are always marked by a casual, offhanded racism that seems more about leveraging power, or scoring verbal points, than any actual conviction. They’re not actually racists; they just happen to talk that way.

And thus Reuben Flagg, Chaykin’s offhandedly, incidentally Jewish hero reveals the limitations of “inclusivity” in mainstream comics. Because the vision that experiences difference—cultural, racial, religious—as an event is a vision that’s fundamentally provincial. In interviews, Chaykin likes to paraphrase the comic-book artist Gil Kane: “One of the problems with comics is that they mistake gravity for enormity. I felt I could do more important, serious work by being funny than by striking adolescent misrepresentations of adulthood.”