Is Jewish Control Over the Slave Trade a Nation of Islam Lie or Scholarly Truth?

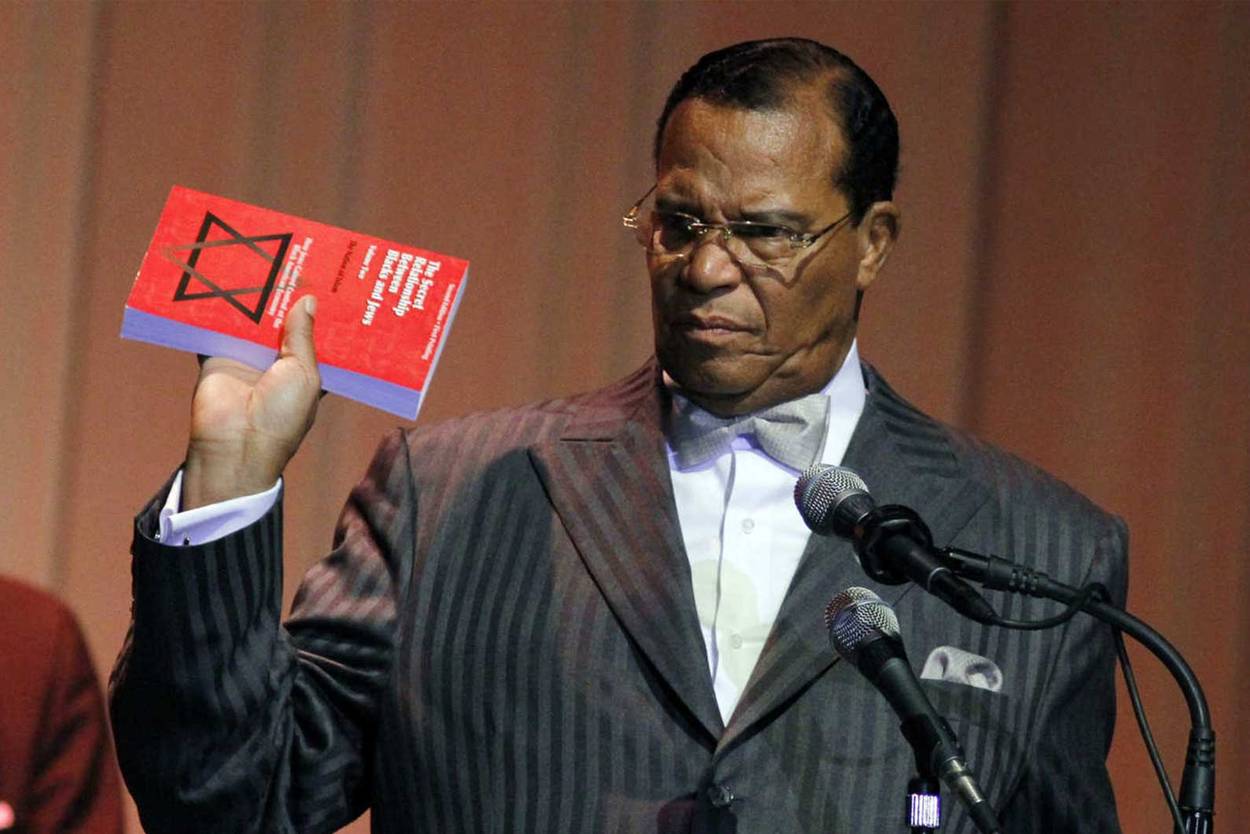

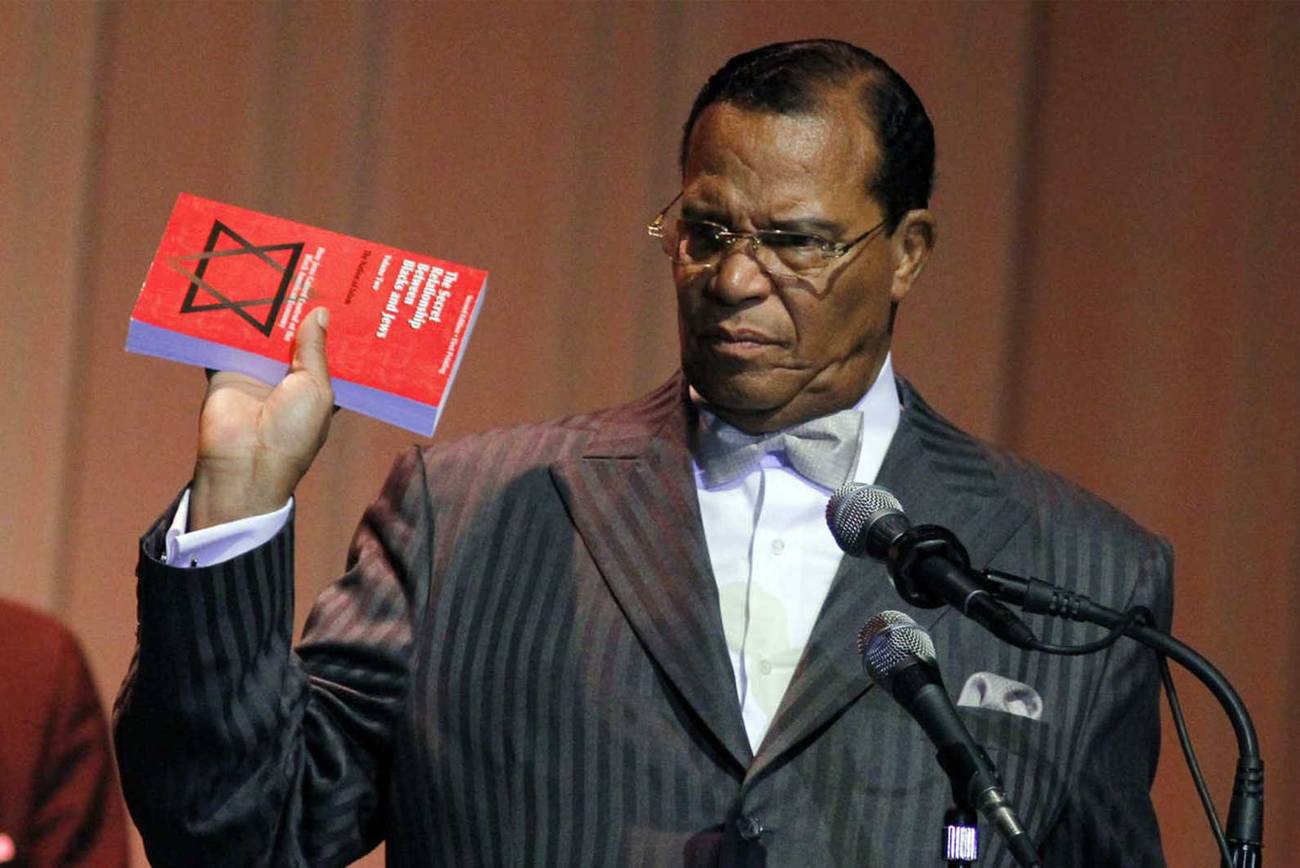

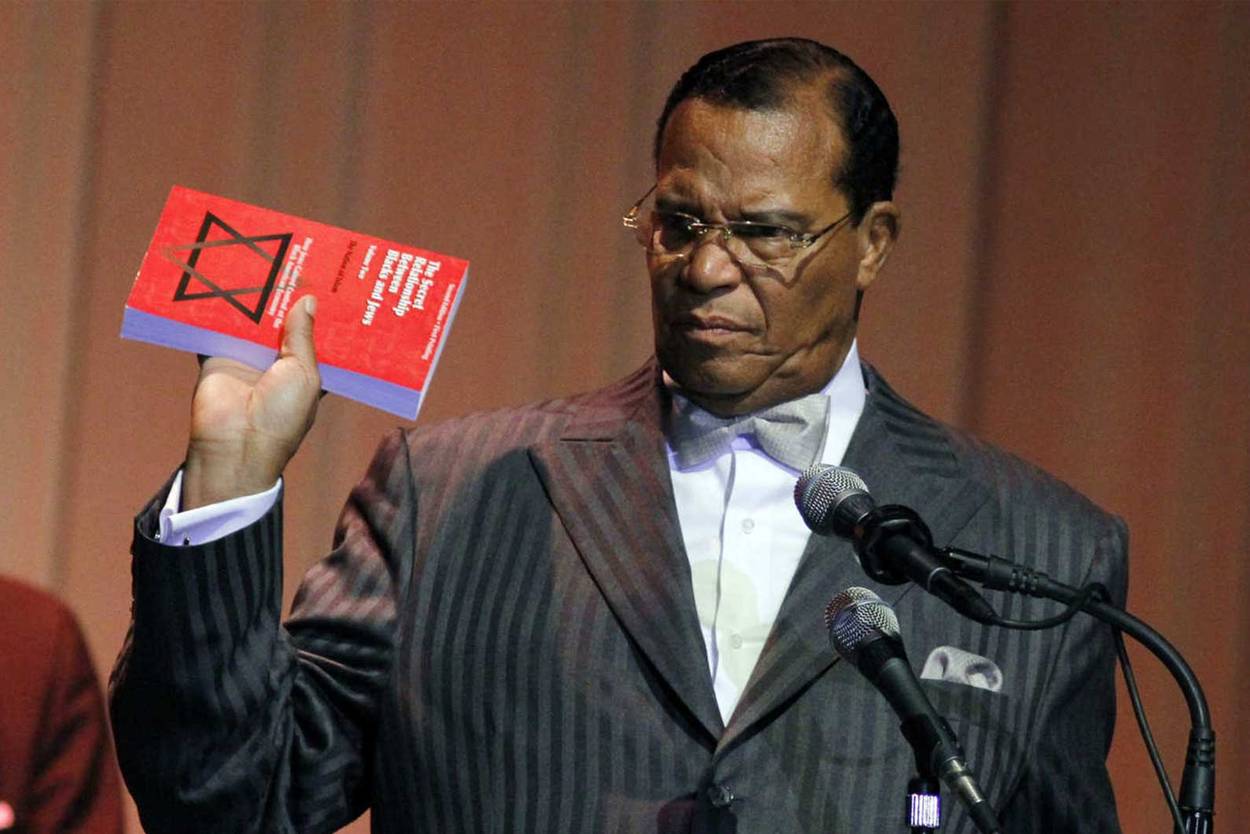

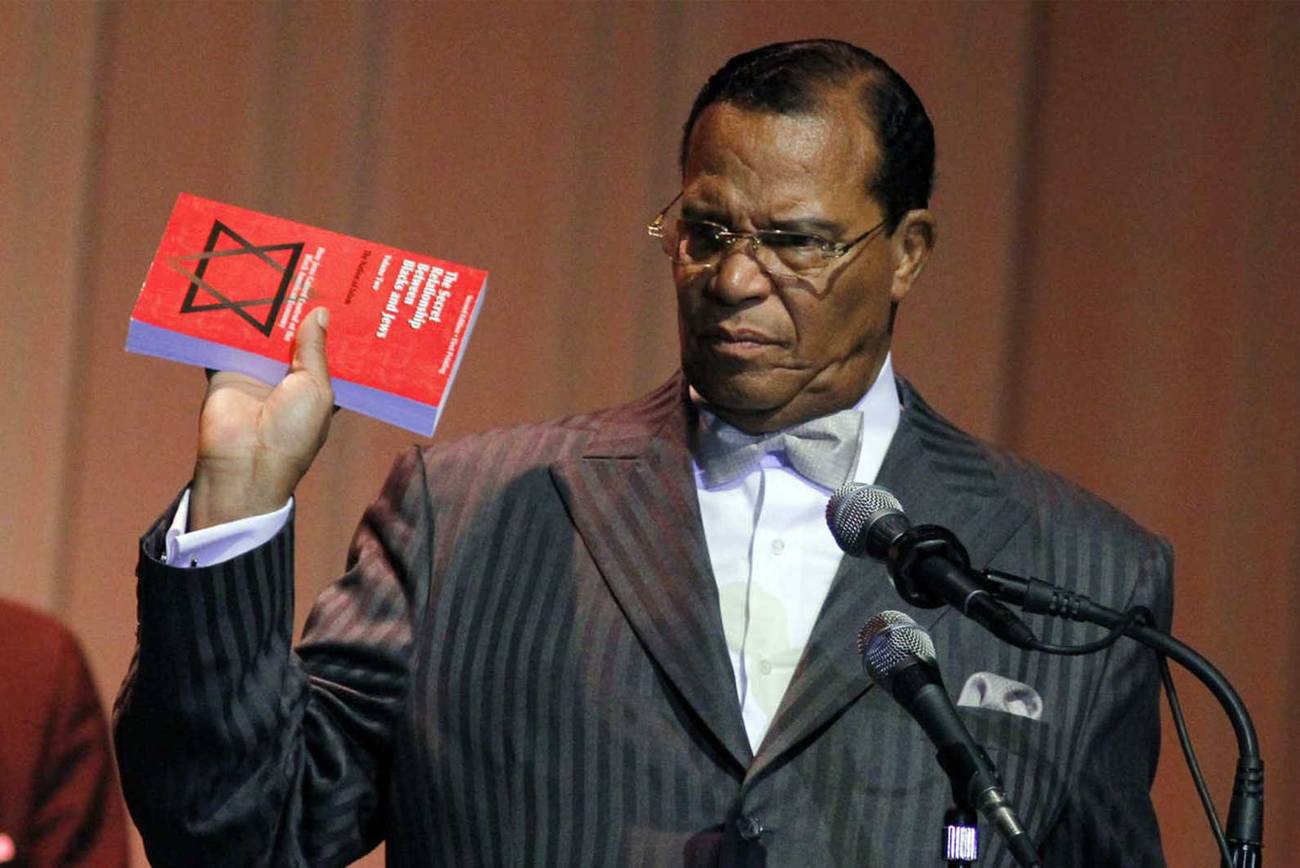

When Louis Farrakhan says, ‘You need to get this book,’ he means an insidious 1991 title whose claims continue to echo today

At a recent rally for the Voting Rights Act in Alabama, Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam spoke of the Jews. Surrounded by a cadre of tall, glowering men with snappy suits, sunglasses, and folded arms, Farrakhan addressed an enthusiastic crowd in terms that would be unsurprisng to anyone familiar with his unique way of stirring up an audience. After asserting, with a benevolent smile, that he is not an anti-Semite, Farrakhan dove into his feelings about Jews: “I just don’t like the way they misuse their power,” he said. “And I have a right to say that, without being labeled anti-Semitic, when I have done nothing to stop a Jewish person from getting an education, setting up a business, or doing whatever a Jewish person desires to do.” The remarks were evocative of the sentiments he has shared widely throughout his decades-long career as a public figure—namely, that blacks should not trust Jews.

It’s a position that Farrakhan has articulated for years. Perhaps the most noxious element of Farrakhan’s position, that the Jews are no friends to African Americans, has been locating its point of origin in the idea that Jews were heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade. In 1991, the Nation of Islam, a branch of the Black Nationalist Movement, published a copiously footnoted book intriguingly titled The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews. The Nation of Islam won’t say who wrote the book, though in one sermon, Minister Farrakhan attributes it to an individual by the name of “Alan Hamet.” It is published by “The Historical Research Department of the Nation of Islam,” which has three titles to its credit: The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 1, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 2, and a third book simply titled Jews Selling Blacks. “This is a scholarly work, not put together by nincompoops!” Farrakhan exclaimed about The Secret Relationship during a sermon. The book claimed to provide “irrefutable evidence that the most prominent of the Jewish pilgrim fathers [sic] used kidnapped Black Africans disproportionately more than any other ethnic or religious group in New World history.” Awash in footnotes and quotes from reputable, often Jewish, historians, the book provides such details as lists of slaves, lists of Jews, and their relationship (disproportionate, The Secret Relationship concludes). “The history books appear to have confused the word Jews for the word jewel,” the anonymous author states. “Queen Isabella’s jewels had no part in the finance of Columbus’ expedition, but her Jews did.”

Felicitous quotations aside, do scholars take the work seriously? For years, Eli Faber, professor of history at CUNY and author of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight, has assigned portions of The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews to his graduate class in order to teach them about anti-Semitism. But, he said, this has had some unintended consequences. “Just two weeks ago, my students found those sections convincing,” he told me in an interview in June. “The academic framework of that book is very convincing. ‘If it’s science, it must be good,’ they think. It has all the trappings of that which confers legitimacy: footnotes, citations, sources. If you don’t think very deeply about it, you’re not going to stop and say, hold on. People get very swept up in it.”

***

The Secret Relationship alleges that Jews were over-represented in the slave trade, but it goes about doing so in a funny way. For the author, the fact that Jews participated at all is tantamount to proof that without Jewish money and Jewish traders, the entire industry would have collapsed. For example, the book’s anonymous author cites the fact that in 1774, the Jews of Jamaica owned 310 slaves, which, horrific as it is, is only 4 percent of the total slave population in Jamaica at that time (7,424). A grand total of 12 Jews owned plantations, and yet this doesn’t stop the author from concluding that Jews dominated the trade.

Faber found during his more recent scholarly research with British Naval Office records that in 18th-century Britain, Jews actually were not heavily invested in the trading part of the slave trade. “Overwhelmingly,” Faber said, “Jewish merchants and shippers were not involved at all; they represent a minuscule portion of owners of ships.” While Jews did own slaves, he found, “their ownership was directly proportionate to their numbers.” Both were about 18 percent. The two companies with slaving ventures had small numbers of Jews among their owners: The Royal Africa Company had none until 1712, and the South Sea Company always had a handful of Jews, though interestingly, “those Jews were more likely than non-Jews to invest heavily,” Faber says.

“The numbers just aren’t there to support the view,” said Faber. “Jews were involved, but to an insignificant degree. That doesn’t absolve them of that guilt, but everyone made money off African slaves: Arabs, Europeans, Africans,” he said. “And there was no attempt to deny it—the Nation of Islam used Jewish sources.”

And indeed, most black intellectuals were never convinced by The Secret Relationship. “You can’t even say that Christians across the board were slave-traders!” said Hilary Shelton, Washington bureau director and senior vice president for Advocacy for the NAACP. “There is not a religion that doesn’t have someone doing some dastardly thing. Did you know that in Ku Klux Klan’s handbook, it states specifically that one must be a devout Catholic?[*] And this is problematic for the relationship between the two communities, which has been so important to us.”

The Secret Relationship emerged from a very specific historical moment in which social forces threatened the previously strong relationship that Blacks and Jews shared, based on the similarity of their persecution and the sympatico nature of the fight for civil rights. This relationship became strained in the second half of the 20th century, as Paul Berman wrote in The New Yorker in 1994, by differences on specific questions of public policy, such as affirmative action. The Jewish liberals opposed it, according to Berman, as a betrayal of the tenets of liberalism, insofar as affirmative action means “people should be viewed primarily as members of groups, not as individuals.” Furthermore, the Black Separatist movement in the late 1960s, through its identification with the Third World, chose to support the Palestinians, which Berman says was felt to be a betrayal by their Jewish friends.

Tensions came to a head in the 1990s, when demagogues like Leonard Jeffries (whose nephew, Shavar, is a candidate for Mayor of Newark, N.J.) and Khalid Abdul Muhammad gave incendiary lectures blaming Jews for the slave trade and the racist depiction of Blacks in Hollywood. Around that time, the Nation of Islam published The Secret Relationship. “They thrived because they were in protest against the Civil Rights Movement,” said Berman of Farrakhan and his ilk. “Black Nationalism raised some legitimate questions about cultural identity, how to present oneself to the rest of the world, how to self-identify and culturally define an autonomous community. But this had nothing to do with civil rights.” Farrakhan’s confusion led people to anti-Semitism, what Berman calls “the mother of all conspiracy theories.” The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews was both a catalyst and a symptom of a particular historical moment: The anti-Semitic content allowed Farrakhan to weave racism against Blacks into a larger Third World context, making it a worldwide phenomenon, with Jews at the helm.

In 1992, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. wrote a bleak op-ed for the New York Times about the spate of “Black Demagogues and Pseudo-Scholars” whose culture had produced The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews. In it, he criticized the book for its troubling assumption, in a critique that many Jews could stand to internalize, namely, that “underlying [The Secret Relationship] is … the tacit conviction that culpability is heritable. For it suggests a doctrine of racial continuity, in which the racial evil of a people is merely manifest (rather than constituted) by their historical misdeeds. The reported misdeeds are thus the signs of an essential nature that is evil.”

Gates concluded in 1992 that the reason for black anti-Semitism is a case of Rochefoucauld’s truism, that “ ‘We can rarely bring ourselves to forgive those who have helped us.’ For sometimes it seems that the trajectory of Black-Jewish relations is a protracted enactment of Rochefoucauld’s paradox.”

But aside from the sociological problems the book generated, it was also factually incorrect. “The Secret Relationship gives a false and distorted picture,” said David Brion Davis, Sterling Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University and author of a trilogy on slavery, the first part of which won the Pulitzer in 1967 and the second of which won the National Book Award in 1976. “Of course, some Jews were involved in the slave trade. Every European Western nation was.” There were also some regions in which the slave trade was more accessible to Jews—Rhode Island, Newport, Holland, to name a few striking examples. “The Dutch Jews weren’t persecuted, so there were quite a few who were involved.”

Davis has been writing about slavery for over 60 years. An emotional writer, he wrote feelingly in the New York Review of Books in 1994 about the slave trade and the Jews, arguing that the historical record itself is infused with the kind of inaccuracies found in The Secret Relationship. He writes:

Much of the historical evidence regarding alleged Jewish or New Christian involvement in the slave system was biased by deliberate Spanish efforts to blame Jewish refugees for fostering Dutch commercial expansion at the expense of Spain. Given this long history of conspiratorial fantasy and collective scapegoating, a selective search for Jewish slave traders becomes inherently anti-Semitic unless one keeps in view the larger context and the very marginal place of Jews in the history of the overall system. It is easy enough to point to a few Jewish slave traders in Amsterdam, Bordeaux, or Newport, Rhode Island. But far from suggesting that Jews constituted a major force behind the exploitation of Africa, closer investigation shows that these were highly exceptional merchants, far outnumbered by thousands of Catholics and Protestants who flocked to share in the great bonanza.

Davis continues:

To keep matters in perspective, we should note that in the American South, in 1830, there were only 120 Jews among the 45,000 slaveholders owning twenty or more slaves and only twenty Jews among the 12,000 slaveholders owning fifty or more slaves. Even if each member of this Jewish slaveholding elite had owned 714 slaves—a ridiculously high figure in the American South—the total number would only equal the 100,000 slaves owned by Black and colored planters in St. Domingue in 1789, on the eve of the Haitian Revolution.

Furthermore, to count Jews is to ask the wrong question. Rather, Davis argues, the more important thing to keep in mind is that “Jews found the threshold of liberation from second-class status or worse, in a region dependent on Black slavery.”

At 60, Davis converted to Judaism, after being married to a Jewish woman for 16 years. “Judaism has contradictory aspects when it comes to slavery,” he said. “There’s a distinction between Jewish and Gentile slaves. There’s also a sense of having been slaves, and having been liberated, which was crucial for the Abolition movement. But of course, defenders of slavery also drew on the Torah,” he said.

Another historian, Jonathan Schorsch of Columbia University, has also written about the slave trade—most recently in his 2009 book Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World and in an article published in the journal Jewish Social Studies. Schorsch sees even the facts surrounding Jewish involvement as being contentious. “There seem to have been a handful of Jewish firms, proportionate to their population. A lot of things that don’t make anyone feel good.” About The Secret Relationship, Schorsch said, “The claim in the narrow sense is just. Why are they harsher toward Jews? Is it because they are afraid to antagonize Christians? Jews did their share of persecuting and discriminating, of being persecuted and discriminated. Neither Blacks nor Jews are as perfect as one would wish. Did Black Nationalists want to puncture Jewish pride? There are real stakes here—government funding and so forth. Then there’s the victim game—who’s the biggest victim? It makes some Jews very uncomfortable.”

Schorsch is critical of one of the positions he has encountered in his research, in which Jewish historians argue that Jews were excluded from the slave trade due to persecution from Christians. Jews were not allowed to own land, the argument goes, disabling their participation in the big slave industries. But for Schorsch, this position makes a crucial analytic error, namely, “Such a defense assumes that power is a kind of zero-sum game in which only those ‘on top’ possess it, leaving everyone else without,” he writes. “But power’s circulation throughout society must be continuously negotiated by all of the involved parties, not just those on top.

“There’s a tension in Jewish historiography,” Schorsch continues. Historians wish to represent Jews as “not just martyrs and victims, but agents and actors—there’s their place in business, their settlement in the New World. These are Jewish triumphs. But for Blacks, of course, these are not triumphs but problems.”

***

Farrakhan’s continued tirades aside, the historical moment that produced The Secret Relationship seems, at least according Paul Berman, squarely behind us. “That sort of crackpot conspiracy theory has receded to the margins,” Berman said. “Blacks have been politically mobilized to the mainstream. It’s thrilling to learn that in the past two elections, Black voter participation surpassed that of whites. There is no political expression of the crackpot wing.”

“So the innate rationality of the Black community won out over the crackpot claims?” I asked.

“Yes,” Berman said. “I have a feeling we’re in a different era. Don’t you?”

Correction, Aug. 22, 2013: We regret that due to an editing error, this piece initially misnamed one of the founding members of the NAACP. She is Mary White Ovington, not Atherton, and she was Unitarian, not Jewish, though a number of other founders of the NAACP were Jewish.

correctionEditor’s note:, September 14, 2020: The article failed to note that the Catholic Church was a prime target of the KKK.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.