Smoke in the Air

In the ‘cosmic and frightening’ Sapir Prize-winning The Ruined House, by Israeli expatriate Ruby Namdar, the secular modern world and the ancient divine mysteries coexist

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

In literature, as in so many other ways, American Jews and Israeli Jews live in separate worlds. American Jewish readers who are dependent on translation to read Hebrew fiction are mainly limited to a few marquee names: Grossman, Oz, Keret. Small presses, including academic and Jewish publishers, make an important contribution by bringing lesser-known Israeli writers into English, such as Gail Hareven and Zeruya Shalev. But the view of Israeli literature from New York bears little resemblance to the view from Tel Aviv. And the same is true the other way around, even though English is more accessible to Israelis than Hebrew is to Americans. The American Jewish canon—Roth, Bellow, Malamud, Ozick—is surprisingly little known in Israel, and more than one Israeli reader has described coming to these books as a revelation.

The Ruined House, the newly translated novel by Ruby Namdar, is the rare book to have a foot in both literary cultures. That is because Namdar, a native Israeli who writes in Hebrew, is also a resident of New York City, where the book is set. When The Ruined House was published in Israel in 2013, it was the first novel written by an expatriate to win the Sapir Prize, Israel’s equivalent of the Pulitzer. Subsequently, the prize rules were changed to prevent any writer outside Israel from winning again—an act of cultural defensiveness that bespeaks a narrow view of what the Hebrew language can do, and who it is for. What the Jewish literary world needs is surely more communication between cultures, rather than less.

That is exactly what Namdar accomplishes in this cosmic and frightening book. A reader who picks up The Ruined House might take it, at first, for a work by an American author. Indeed, in outline it sounds deceptively similar to books like Herzog and The Anatomy Lesson, in which a male Jewish intellectual undergoes a midlife crisis. But in Namdar’s hands, this classic trope is fascinatingly estranged. Indeed, Namdar redefines what it means to tell a Jewish story. Instead of simply a comedy about “Jewish” traits like neurosis, alienation, and over-intellectuality, The Ruined House is a human drama with cosmic dimensions, in which past and present intersect in mysterious, often frightening ways.

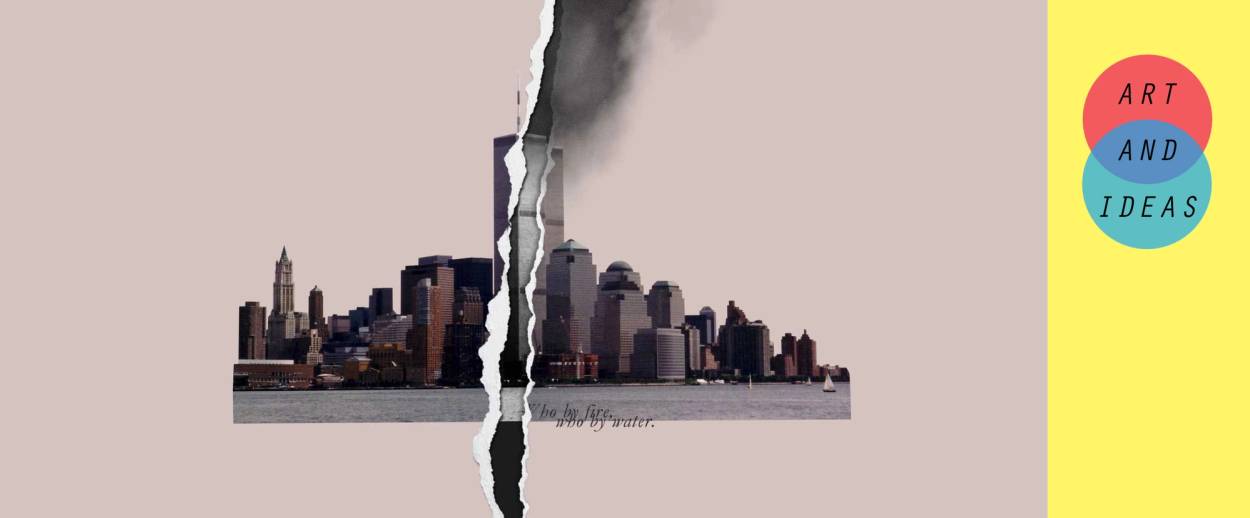

That crossing begins on the novel’s first page, which is dated precisely to Sept. 6, 2000. On that day, Namdar writes, “the gates of heaven were opened above the great city of New York, and behold: all seven celestial spheres were revealed, right above the West 4th Street subway station, layered one on top of another like the rungs of a ladder reaching skyward from the earth.” It is a vision out of Ezekiel, which seems to place us in a mystical dimension that is totally incompatible with the matter-of-fact subway station. And, in fact, no one on the New York street seems to notice the splendor above: “No human eye beheld this nor did anyone grasp the enormity of the moment,” Namdar writes. Already we are plunged into the central paradox of The Ruined House: The secular modern world and the ancient divine mysteries co-exist, but in parallel dimensions that cannot communicate.

Except, for some mysterious reason, they do meet in the person of Namdar’s protagonist, Andrew Cohen. The Ruined House, like those classic books by Bellow and Roth, is an extended tour of the world through the mind of a richly imagined protagonist. We follow Andrew to parties and doctor’s offices, on drives through Westchester and walks through Morningside Heights. The chief pleasure of the book lies in Namdar’s evocation of Andrew’s thoughts and feelings and observations, in a style that ranges from the colloquial to the poetic. More than most novels, The Ruined House lives in the quality of its prose, which renders the achievement of the translator, Hillel Halkin, all the more impressive.

Andrew Cohen is an unlikely choice for a portal between the Jewish past and the Jewish present, since he has no interest in God or Jewishness. Early in the book, a refrain comes to his mind: “Who by fire, who by water: wasn’t that a Leonard Cohen song?” Leonard Cohen got it from the Yom Kippur liturgy, of course, but Andrew Cohen only knows it from Leonard Cohen—a succinct diagnosis of the state of contemporary American Jewry. Andrew actually does attend Yom Kippur services, but he can’t say exactly why he does: “It was neither a rational decision nor the outcome of lengthy debate, but an unthinking, almost absent-minded choice.” In any case, he slips out early to go to the opera.

In other words, Andrew is an American Jewish archetype—a New Yorker and an intellectual, a professor of “comparative culture” at NYU. Yet he is not a Woody Allen-ish intellectual, an anxious nebbish. On the contrary, he belongs to the new breed of worldly academic superstars who are equally comfortable in a seminar or a dinner party. His work, what little we see of it, involves producing clever little analyses of pop culture, couched in academic jargon. For a man of mind, he seems inordinately interested in pampering his body—workouts at the gym followed by elaborate feasts, which he takes pride in cooking himself. He can pursue this epicurean lifestyle because, years ago, he divorced his wife and left his two daughters; he is proud of his “wisdom and courage in having left home, with its ceaseless, cloying clamor of family life, for the personal and aesthetic independence of the marvelous space inhabited by him now.”

As this passage suggests, Andrew Cohen is heading for a fall, and a deserved one. Over the course of 500 pages, which chronicle the year between September 2000 and September 2001, fall he does—losing his looks, his health, his girlfriend, his promised promotion, and his overweening confidence. But this humbling—to borrow the title of Philip Roth’s novel about the hard passage of an aging man—is unlike any story of midlife crisis we’ve read before. That is because Andrew’s transformation is accompanied, if not actually prompted, by visions and visitations that he himself barely understands—visions of the Temple in Jerusalem, of priests and sacrificial bulls, of blood and fire.

For it turns out that the Temple—in Hebrew the beit hamikdash, the Sacred or Sanctified House—is the “ruined house” of Namdar’s title. And while “Cohen” is just a Jewish name today, Namdar remembers—and wants us to remember—that it originally meant “priest,” and designated the caste of Jewish priests who officiated in the Temple. Andrew Cohen bears that legacy somewhere deep inside—in his DNA, or his soul, or his Jungian unconscious. When he sees flashes of ancient Jewish life, he is peering into the collective past—and the joke, and the tragedy, is that he has absolutely no idea what he is seeing.

Andrew’s story thus proceeds on two tracks, mirroring the many dualisms of Jewish life: modern and ancient, secular and religious, New York and Jerusalem. On the surface, his ordeals can be explained as simply the indignities of age. His relationship with Ann Lee, a former student half his age, starts to wilt as Andrew grows uninterested in sex, and then incapable of it. He finds himself gaining weight, unable to keep up his exercise regimen. He has graphic nightmares in which he is castrated, his loss of potency made concrete. Even cuisine loses its appeal: “He dug his fork into a quail, detaching a piece of gray, fibrous meat and putting it cautiously in his mouth. It was thick and cartilaginous, revolting.”

But the more the reader knows about Judaism, and particularly about traditional Jewish rituals and taboos, the more pointed and meaningful Andrew’s aversions seem. One night he wakes up next to Ann Lee to find she has begun to menstruate. His body and the sheets are bloody, and he reacts with unreasoning, inexplicable horror: “He felt a new surge of fury, disgust, and panic. He had to wash himself, to scrub his polluted flesh with soap and scalding hot water. The voice of reason, echoing in the empty chamber of his mind, was hollow and unconvincing. Why on earth should he feel this way? What had happened, for goodness’ sake? She had gotten her period, that was all.”

Andrew does not know that sex with a menstruating woman is taboo according to Jewish law, yet somehow his subconscious has retrieved this knowledge—from a previous incarnation, perhaps?—and he can’t help reacting accordingly. Similar episodes of disgust and pollution visit Andrew when he has a nocturnal emission—another source of ritual impurity according to Jewish law—and when he contemplates cooking a piece of non-kosher meat. Indeed, his predilection for cooking meat itself comes to seem like an atavistic impulse, a return to his priestly ancestors’ role of tending to the Temple sacrifices.

Namdar does not make these parallels fully explicit, but he helps the reader along by inserting, at intervals throughout the novel, the story of an ancient High Priest performing the atonement rituals in the Temple on Yom Kippur. These pages are arranged like pages of Talmud, with a narrative at the center flanked by the Biblical and Talmudic passages from which Namdar takes his details. This High Priest, the reader comes to understand, may be Andrew Cohen’s distant ancestor. They inhabit utterly different worlds, yet the two men are somehow connected. This is exactly the kind of primal connection to Jewishness that so many American Jews feel the lack of; yet when Andrew experiences it, it is terrifying and suffocating.

One of the best extended sequences in the book follows Andrew through Manhattan on an August day, as he feels increasingly disturbed by the smell of smoke in the air. Finally, he can barely breathe, yet he can’t find the source of the smoke—nothing seems to be on fire. For the reader, however, this invisible smoke seems like a double visitation, from the future and the past. It is August 2001, just weeks before the Sept. 11 attacks: is Andrew inhaling the smoke that is about to cover downtown Manhattan? At the same time, it is the 8th of Av—each section of the novel is headed with both the English and the Hebrew date—which is the day before the anniversary of the burning of the Temple. Is he remembering the smoke from the ruined house, which covered Jerusalem 2,000 years before?

Namdar allows both suggestions to linger. Each moment of history—not just the past but those still to come—is somehow simultaneously present in Cohen’s life, and in our own. Jewishness, The Ruined House intimates, is a matter of waking up to this historical connection, with all its splendor and horror. The originality and power of this idea, along with Namdar’s fertile power of observation and evocation, make The Ruined House a new kind of Jewish novel, which everyone interested in Jewish literature should read.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.