Socialism Without Antisemitism

From Karl Marx on down, early socialist movements and many of their successors gave themselves over to virulent antisemitism—with the shining exception of Comte Henri de Saint-Simon and his disciples

In “On the Jewish Question,” published in 1844, Karl Marx famously stood the notion of Jewish emancipation on its head, writing that “Jews have emancipated themselves insofar as Christians have become Jews,” i.e., admirers of Mammon. Far from being ghettoized and excluded, deprived of basic freedoms, and subjected to horrific individual and mass accusations and physical violence for centuries, Marx explained to his followers, the Jews of Europe were in fact historical oppressors bent on conquest. “The everyday Jew devoted himself to endless bartering ... It was still Judaism, practical in its nature, that was victorious,” Marx explained. “Egotism permeated society.”

Jews were not only all-conquering, Marx continued, but also maleficent. “We recognize in Judaism, therefore, a general anti-social element of the present time, an element which through historical development—to which in this harmful respect the Jews have zealously contributed—has been brought to its present high level, at which it must necessarily begin to disintegrate. In the final analysis, the emancipation of the Jews is the emancipation of mankind from Judaism.” Case closed.

Quantities of ink worthy of a Talmudic discussion have been spilled explaining away the explicit content of Marx’s essay. But his private writings make it impossible to assert that Marx was not a carrier of a virulent strain of racist Jew-hatred that has infected some of his followers to this day. In a letter to Engels on July 30, 1862, attacking Ferdinand Lasalle, Marx’s Jewish opponent among socialists, for example, Marx wrote that “It is now quite plain to me—as the shape of his head and the way his hair grows also testify—that he is descended from the negroes who accompanied Moses’ flight from Egypt (unless his mother or paternal grandmother interbred with a nigger).”

But even Marx at his worst did not approach the venomous opinions of his rival, the father of anarchism, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Proudhon expressed his feelings for Jews in his notebooks in an entry dated Dec. 26, 1847, an entry less anti-capitalist than exterminationist: “Jews. Write an article against this race that poisons everything by sticking its nose into everything without ever mixing with any other people. Demand its expulsion from France with the exception of those individuals married to French women. Abolish synagogues and not admit them to any employment. Demand its expulsion. Finally, pursue the abolition of this religion. It’s not without cause that the Christians called them deicides. The Jew is the enemy of humankind. They must be sent back to Asia or be exterminated.”

Rare is the radical movement of the early- to mid-19th century, particularly in France, that did not contain an antisemitic component. An exception to this sorry rule, a socialist movement that not only did not hate the Jews as an article of faith, but one in which Jews occupied leadership positions, managed funds, and offered intellectual guidance, were the utopian socialists inspired by Count Henri de Saint-Simon.

Saint-Simonism was a small movement, and even classifying it as socialist is questionable: There are entire volumes of its founder’s collected works in which the word “socialism” never makes an appearance. Precisely because of the movement’s small size, Jews, of which there were seldom more than a dozen in its ranks, played a disproportionate role in its actions and ideas. More importantly, it was the former Jewish disciples of Saint-Simon who, both while involved in the movement and even more, after their departure from it, did most to realize the founder’s goals.

The ideology of Saint-Simon himself was well and fairly summarized by one of his later critics, Fredrick Engels, in his Socialism, Utopian and Scientific. “In Saint-Simon, there is less a class struggle than “an antagonism between ‘workers’ and ‘idlers.’ The idlers were not merely the old privileged classes, but also all who, without taking any part in production or distribution, lived on their incomes. And the workers were not only the wage-workers, but also the manufacturers, the merchants, the bankers.” The idlers had long since demonstrated that they were no longer capable of intellectual and political leadership, and those roles now fell to “science and industry, both united by a new religious bond, destined to restore that unity of religious ideas which had been lost since the time of the Reformation—a necessarily mystic and rigidly hierarchic ‘new Christianity.’”

There is nothing here of the later socialist vision of class conflict, in no small part because capitalism had not sufficiently developed in France during Saint-Simon’s lifetime. Saint-Simonism was an elitist revolt: The role of the industrious bourgeois was to improve “the lot of the class that is the most numerous and the most poor (“la classe la plus nombreuse et la plus pauvre”). Saint-Simon was dedicated to rejuvenating and superseding the existing Christianity with a new Christianity, since the former, “for eighteen centuries, has been in a state of almost absolute stagnation in the moral realm.” The practical end of the new religion was “the exploitation of the terrestrial globe.” Since the goal of human philosophy was the “total exploitation of the globe,” Saint-Simon wrote to one of his disciples, it is necessary to “combine all industrial, scientific, and sentimental forces in order to obtain this result as rapidly as possible.”

The evil role of the Jews in society appears nowhere in Saint-Simon’s writings, though he was not perfectly immune to the ambient antisemitism of Catholic France. When reviewing the role of Jews historically, he characterized Judaism as “somber, concentrated, and devoured with the pride inspired in it by its more than earthly nobility and by the humiliation in which it was forced to live.” “Devoured with pride,” however unattractive a characterization, was mild when compared to other figures of the period, both within the socialist movement and without.

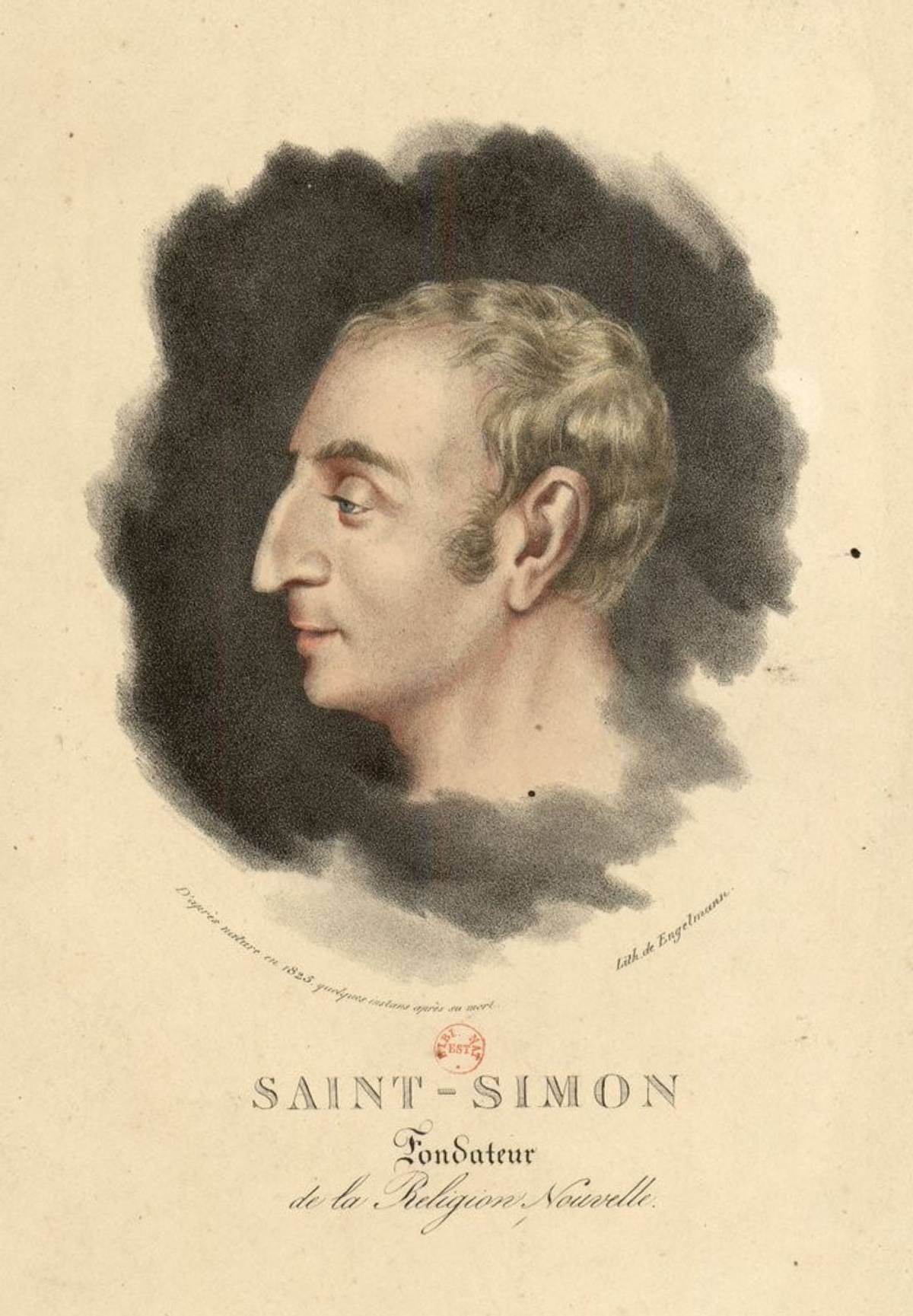

Claude Henri de Rouvroy Comte de Saint-Simon, who developed these ideas, was a member of the nobility with ancestral lands in the north of France. His ancestors included the greatest of all chroniclers of France’s royalty, his cousin Louis de Rouvroy, Duc de Saint-Simon.

The count led an adventurous life, fighting with the French forces in America during the Revolution. Back in France, during the Revolution he was arrested at the time of the Terror (perhaps in error) and was saved by the downfall of Robespierre. During the Directorate that followed Robespierre’s fall he lived the good life, maintaining a salon and, setting the tone for his later years, involving himself in ambitious intellectual and financial schemes. As a biographer put it, “Learning intrigued him as much as finance,” which was amply demonstrated by the life he lived until his death, as he squandered his fortune, spending much of his final two decades begging friends and relatives for funds. He often combined his love for ideas with his financial need, writing odd scientific texts which he would send off to well-known individuals, including begging letters with his writings. Dismissed by the scientists to whom he addressed his theories, he nevertheless had visions of an even grander role, one that had inspired his putative ancestor Charlemagne: the setting aright of Europe by founding a new political, social, and religious order.

After Napoleon’s defeat, during the Bourbon Restoration, he became an important voice in defense of the nobility’s rivals, the bourgeoisie, publishing tomes of social theory, newspapers whose titles expressed Saint-Simon’s focus, like L’Industrie, Le Politique, L’Organisateur, Du Système Industriel, and Catéchisme des Industriels, and articles criticizing the Catholic Church and the nobility, the main obstacles to France’s progress. In February 1820, he published an article in which he imagined the consequences of the deaths of France’s leading scientists, artists, bankers, industrialists, comparing this to the effect of the deaths of its leading nobles, to the detriment of the latter. The assassination of the Duc du Berry on Feb. 13 of that year led to his arrest as a moral contributor to the crime, though he managed to escape punishment.

In 1823, still living in poverty and reduced to begging for financial assistance, he attempted suicide, but he was discovered by a physician in time to save his life.

Having reached the seeming depths, it was around this time that he was joined by a circle of supporters that would support him politically and financially in his final years and carry on his work after his death in 1825. Significantly, most of these new disciples were Jews, including Olinde Rodrigues, soon to be the managing editor of Le Producteur, a newspaper dedicated to Saint-Simon’s ideas founded immediately upon the master’s death. Yet another Jewish disciple, Léon Halévy, served as Saint-Simon’s secretary and wrote the prospectus for the paper in preparation for its appearance. The movement and its founder’s eternal optimism was expressed by the newspaper’s motto: “The Golden Age, which until now blind tradition situated in the past, is before us.”

In his final work, Le Nouveau Christianisme, Saint-Simon made clear his messianic role, asserting, doubtless with his Jewish followers in mind, that “[t]he portion of the Jewish people which remained foreign to the spiritual reign of the Messiah will surrender upon seeing the arrival of his temporal reign, and all prophecies will be fulfilled for all the prophecies are true”.

Saint-Simonism grew much faster after the death of its founder, or as Sébastien Charléty, the first great French historian of the movement put it, “The history of the Saint-Simonians begins the day of Saint-Simon’s death.” A note in Saint-Simon’s collected works reports that Olinde Rodrigues “without any question stood in the front ranks. He boldly made this primacy clear at the very grave of Saint-Simon, taking control of the leadership of the school immediately upon the return of the funeral cortege.” This attempted coup within the movement was quickly short-circuited when fellow disciple Prosper Enfantin, who had missed the funeral and had only met Saint-Simon once during his lifetime, took the movement in hand. Olinde, as a true Saint-Simonian, recognizing Enfantin’s superior abilities as a leader of men, willingly surrendered the leading role.

Le Producteur, the final Saint-Simonian journal published in the founder’s lifetime expired in 1826, and the movement then relied on personal contact as a means of expanding. Olinde Rodrigues brought into the movement his brother Eugène, who would publish an important text on Saint-Simonism and religion. The brothers Emile and Isaac Pereire, cousins of the Rodrigueses, who went on to found the great French bank Credit Mobilier, which built the first national railroad in France, also joined the movement. Léon Halévy remained part of the post-Saint-Simon movement, and he was joined by the baptized Jew, Baron d’Eichthal.

The attraction of Saint-Simonism to young French Jews can be explained by the atmosphere of the period that followed the overthrow of Napoleon I. The Bourbon Restoration returned power to the Church and put roadblocks before the advancement of Jews. Olinde Rodrigues, for example, was unable to attend the Ecole Normale Supérieure, from which Jews were banned, instead attending the Polythechnic. In fact, as the historian Frank Manuel has maintained, Olinde Rodrigues, denied the academic path he truly desired by the anti-Jewish restrictions, as were his cousins the Pereires, took one of the few routes available to ambitious Jews under the Restoration by entering the world of finance. Their discontent with this pis aller made a dissident movement like Saint-Simonism attractive.

The Jewish presence in Saint-Simonian circles was at least partially an illusion, though. Yes, the Rodrigueses and the Pereire brothers had origins in the Jewish community in the Iberian peninsula that had settled in France centuries before. But none of them had any ties to the Jewish religion or community. D’Eichthal was baptized, and Halévy, though his father worked at the Jewish Consistory, was resolutely secular and married a non-Jew. What religion they had was the religion of Saint-Simonism, which aimed at erasing old religious ties, at making its believers more just morally, and at seeing to it that “not only will religion dominate the political order but the political order will be in its ensemble a religious institution, for nothing can be conceived outside of God or developed outside of his Law.”

In the largest sense being a Jew or a Christian mattered little for those in the movement. Eugène Rodrigues wrote, in his 1829 Lettres sur la religion et la politique that all former distinctions were a dead letter: “In fact, the disciples of Saint-Simon include former Jews and former Catholics. In principle they are, above all, disciples of Saint-Simon and the old man, whatever he was, has disappeared in them.” It is perhaps in this that Saint-Simonism resembled later revolutionary movements: It is not only the existing religions that had to be changed, but humanity itself.

In the 1830s Jews were a tiny portion of the French population, numbering 73,000 out of a population of almost 33 million. Even so, the centrality of Jews in the Saint-Simonian movement offered a line of attack to its opponents, not least those who offered a competing utopian vision to that of Saint-Simon. However small the number of Jewish Saint-Simonians was (there were never more than a dozen), the fact that those Jews played a prominent role, not only within the utopian movement but also in the growth of French capitalism, made it possible to rhetorically join Saint-Simonism to rising capitalism—to modernity—and present the movement as a Jewish undertaking.

The most virulent version of this line of attack was the multivolume Les Juifs, rois de l’époque (The Jews, Kings of the Epoch) by Alphonse Toussenel, a disciple of Charles Fourier. Fourier’s form of communalism might have been based on visions of love and community, but this didn’t prevent Toussenel from laying the blueprint for the French antisemitic propaganda of both the left and the right in the decades that followed. After praising the Jews for “having produced more brilliant individuals than any other race,” he went on, explaining that “The universal repulsion the Jew has so long inspired was nothing but the just punishment for his implacable pride, and our scorn the legitimate reprisal for the hatred he seemed to bear towards the rest of humanity.”

For Toussenel, “In France the Jew rules and governs. Where do we find written the proofs of this royalty? Everywhere. Everywhere, in all our instructions, in the events of the day, in all the external and internal political decisions, in the votes in the chambers, in the sentences of judges, even in the king’s speeches.” In fact, he asserted, “the Jew possesses all the privileges that were once the prerogative of the monarchy.” The Saint-Simonians benefited from this royal privilege, since “the Jew” has granted Emile Pereire and Prosper Enfantin lucrative posts and enormous profits. “The Jew, exclusive possessor of the administration of transports throughout the kingdom, will soon have more employees than the state.”

This malicious babble goes on for hundreds of pages, dealing with the most varied element of the French political system and society, ending with a call for “The People” to echo his cry: “Death to parasitism! War on the Jews.”

The Blanquist movement, the most intransigent of fighters against the established order, became a center for the expansion of Toussenel’s ideas. Gustave Tridon, a Blanquist and former member of the Paris Commune, published Du Molochisme juif, a book that openly proclaimed hatred of the Jews and their supposed misdeeds, which included human sacrifice. Despite Tridon’s revolutionary socialist politics, he focuses not on Jewish capitalism but on the Jewish religion. “The God of the Semites,” Tridon wrote, “incarnates the destructive principle, honored by Destruction, the god of pride and jealousy, the wicked and deceitful god, enemy of life and nature.” Tridon was followed in his Jew-hatred by other disciples of Blanqui, a man who hated Saint-Simonsm but never wrote a word attacking the Jews.

Much of the antisemitism of the late 19th century in France was based largely on anti-capitalism, which doesn’t mean it was socialist. Some of it was what a French fascist and collaborator called “national anti-capitalism.” The dislocations of French society, the abandonment of the countryside, the growth of large-scale industry, the power of banks, the corruption of the Third Republic, all were put on the backs of the Jews, giving both left-wing and right-wing critics of the dominant capitalist order a common rhetoric of hate.

No one dedicated as much of his life to antisemitism as Edouard Drumont, editor of the newspaper La Libre Parole and author of volumes with titles like “Confessions of an Anti-Semite. “His “masterpiece” was the summation of French antisemitism, La France Juive—a compendium of over a thousand pages of the horrors of the Jewish presence in France, indeed, on Earth. Originally published in 1886, it went through 140 printings in its first two years of publication.

Drumont dedicates a section of his screed to Saint-Simonism, which he surprisingly describes as “one of the most interesting attempts of the human spirit.” Casting aside the role of its founder who, as we said, traced his lineage back to Charlemagne, Drumont describes the movement as “an attempt by the Jew to escape his prison, which was no longer anything but a moral ghetto to become what Heinrich Heine called a “liberated Jew.” Without going over to Christianity, the Jew got around the difficulty by founding a new religion.” Jewish as it was in Drumont’s eyes, Saint-Simonism “was the negation of the Judaism we see at work and which we can call “Freemason Judaism.”

These are as close as Drumont ever got to writing positive words about any Jews of any kind, but he quickly regained control of himself. It is an odd trait of Drumont’s that he differentiates between Ashkenaz and Sephardic Jews, writing of how the “martyrdom” of the Jews of the South “aggrandized” them, while the “public humiliations” suffered by German Jews “plunged [them] into degradation.” Though he asserts that the movement’s “dominant elements” were what he considered the essential negative Jewish traits, “material pleasures, the satisfaction of the here and now, the love of comfort, [and] the cult of money,” he admits that Saint-Simonism “opened up onto grand visions of the future; excluding no one … all the children of the human family were invited to magnificent feasts.”

It is one of the great ironies of the Saint-Simonist movement that Drumont, a man elected to the Chamber of Deputies on an antisemitic ticket; who most loudly proclaimed the guilt of Dreyfus; who held the Jews responsible for almost everything, from the flooding of the Seine to an accidental fire at a charity event, should have, in that final phrase so well summed up the Saint-Simonian vision.

In Enfantin’s hands, the Saint-Simonian movement went further than its founder could have imagined into the realm of a new religion. Saint-Simon’s Jewish disciples were divided in their opinion of this deviation. Olinde had been an early supporter of the shift from a philosophy to a religion, combining this with stressing the role of the stock exchange in assisting the poor. His brother Eugène was a religious seeker, and the depth of his religious view of Saint-Simonism was well described by a 19th-century French historian of the movement: “He loved a young girl and contemplated marrying her until Enfantin opposed it, declaring that the new priests had to dedicate themselves to the new apostolate instead of involving themselves in family ties. The young enthusiast submitted, bid love adieu, and until his final moments [he died in 1830] imposed absolute chastity upon himself.”

Free love was added by Enfantin to the movement’s precepts, as was the search for a female Messiah who would serve alongside him—which this was the final straw for Rodrigues, who was overseeing the finances of the movement, and in 1832 had arranged for loans for which the members would all be responsible for repaying. Though this complicated his departure, he left the movement after Enfantin decreed that only women could assert the paternity of their children.

Halévy left over the deification of Saint-Simon and the exaggerated role of Enfantin, writing an ode in which he sought to rescue the true teachings of the master from the hands of those who wanted to turn the idea into a religion. He wrote: “Others came whose culpable zeal/Abused a grave and a venerable name!/He’s no longer a mortal!/He, the scourge of error, who smashed its word/here he is, a new god, placed like an idol/on an absurd altar.”

The banker’s dream that was Saint-Simonism was most fully realized by Emile and Isaac Pereire, who would go on to become rivals of the Rothschilds’ as Frances major bankers. Yet there was a major difference between the two families. Though they were cutthroat competitors with the Rothschilds, the Pereires claimed not to be interested solely in personal enrichment. Their financial dealings were also a continuation of the progressive ideals of the Saint-Simonians.

According to the historian of Saint-Simonism Frank Manuel, the family’s business ventures “were the fulfilment of a religious mission. God was using their Credit Mobilier as an instrument through which the earth was made to prosper. … The credit system, the canals, the railroads would bring happiness to mankind, and they were the creative agents in this development.”

The Pereires left the movement at around the same time as Halévy and the Rodrigues brothers, leaving just two Jews in key roles: Dr. Simon, the movement’s physicians, and the Baron d’Eichthal, who, according to a 19th-century writer, “studied the Bible at length in order to renew the tradition connecting Judaism and Saint-Simonism.” He even went so far as to lead a delegation of (non-Jewish) disciples to temple on Rosh Hashana, dressed in Saint-Simonian garb, notably the famous shirt that closed in the back, thus requiring the assistance of a brother in order to wear it.

Yet even while the movement was undergoing schism after schism under his leadership, at no point did Enfantin turn on the Jews. As he wrote, “The God of Moses is the same as that of Christ, and of me.”

Mitchell Abidor is a writer and translator who has published over a dozen books on French radical history.