Q&A With Yosef Begun

The great Soviet dissident and refusenik talks about discovering Hebrew, foiling the KGB, and surviving the ‘banya’

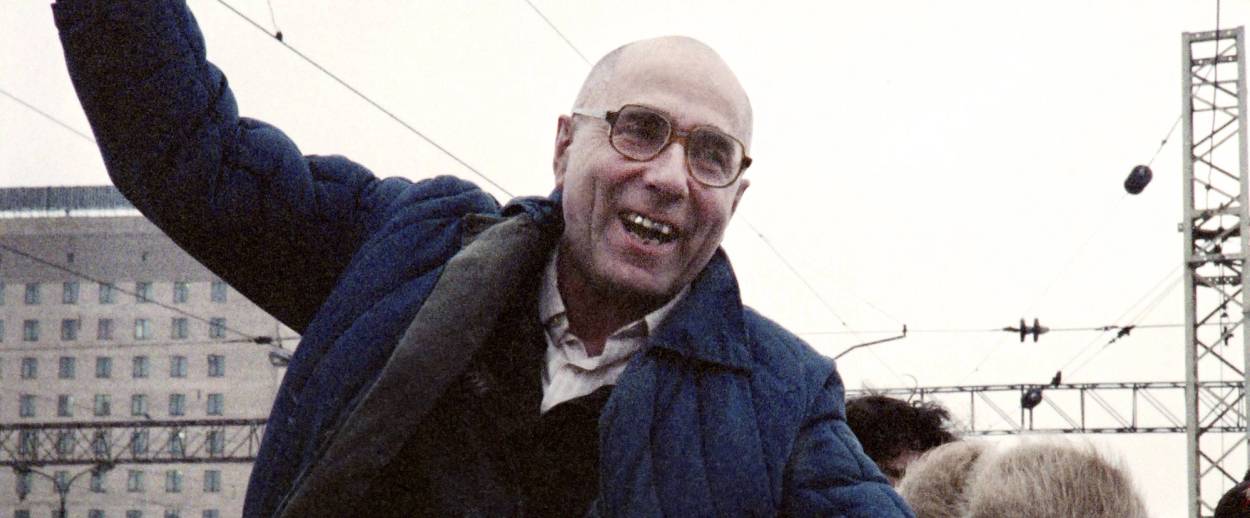

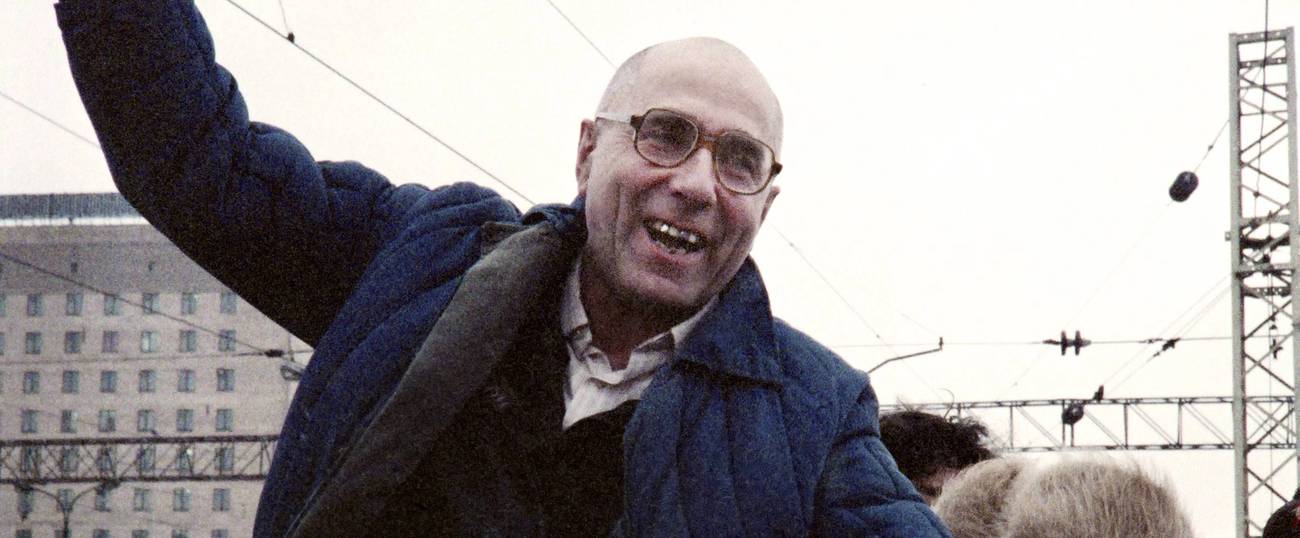

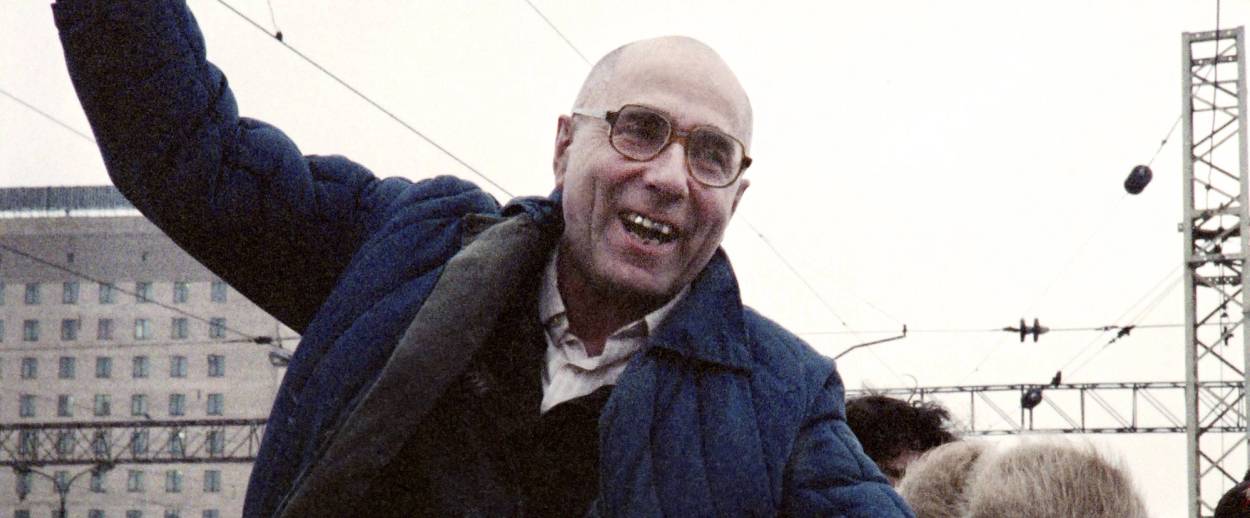

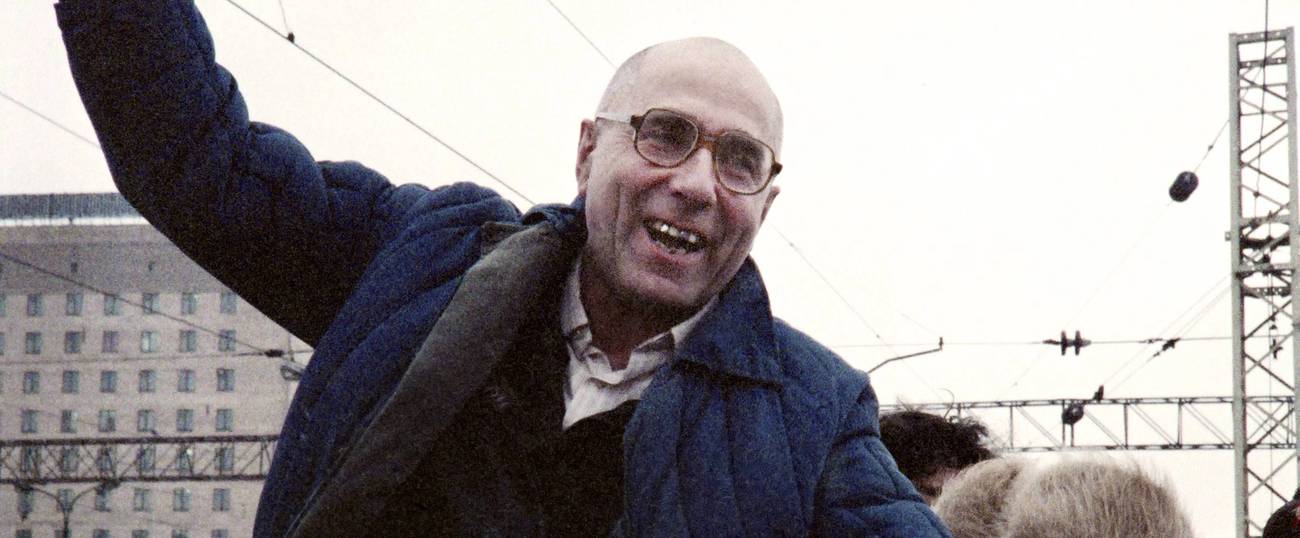

When Elie Wiesel spoke the name “Iosef Biegun” in his speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize on Dec. 10, 1986, it was the first time that most people in Oslo or elsewhere had heard of the 54-year-old Soviet convict then serving a seven-year sentence in the obscurity of Chistopol prison in Kazan, 450 miles east of Moscow, for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” Begun’s two previous convictions were for “parasitism” and being in Moscow without a permit in order to attend a demonstration during the trial of the dissident Yuri Orlov. The sentences for those two crimes had landed him in Siberia but failed to quench his interest in studying and teaching Hebrew and Jewish culture, an occupation that the prosecutor in his case blamed for rousing “nationalistic and emigrational moods among Soviet citizens of Jewish origin, inducing them to leave for Israel.”

In response to their prisoner’s newfound celebrity, Begun’s jailers put him on reduced rations of 900 calories a day. When a small group of protesters, including Begun’s son and his wife, gathered on Arbat Street in Moscow to object to the prisoner’s treatment, they were attacked and beaten by a crowd of 100 plainclothes KGB men and thugs, who also clubbed bystanders and broke camera equipment belonging to foreign journalists.

Begun’s story had an unexpectedly happy ending, though. A week after his wife and son were attacked in the street, he was released from prison, and less than a year later, Begun and his family were allowed to emigrate to Israel. A few months later, on May 3, 1988, Begun met President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office of the White House. There, the president of the United States gave the ex-Soviet prisoner the metal solidarity bracelet engraved with Begun’s name that he had kept on his desk throughout his presidency as a reminder of the fate of the individual human beings held captive by what Reagan called “the evil empire.” A little more than a year after that event, on the night of Nov. 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall was torn down. The cruel empire that Begun and only a handful of other brave dissidents dared to defy from within soon disappeared from the face of the earth, mostly.

Any account of the expansion of human freedom in the 20th century must honor Iosef Begun and his compatriots who suffered in Siberia, in provincial prisons, and in psychiatric wards, just as it honors Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. Like them, the refusniks brought down a monstrous system of tyranny without firing a shot. Like them, they harnessed the power of a stubborn humility to face down official defilement of the human.

The Soviet refusnik movement had at its a core only a few hundred or thousand people, including Anatoly and Avital Sharansky, Yosef Mendelevitch, and others, who defied a seemingly all-powerful state in the name of their right to live as Jews, at a time when such a demand seemed fantastical. Their principled stubbornness, and willingness to sacrifice everything for their dream of being able to think and act freely helped bring freedom to hundreds of millions of other people, whose own national identities and cultures were being systematically eliminated in favor of a far-seeing calculus of justice administered by the Communist Party. The demands of justice, the state argued, trumped the petty attachments of individuals to their own thoughts, feelings, aesthetic ideas, histories, faiths, and traditions, which would be eliminated through a peculiarly Soviet combination of bureaucratic tedium, systematic untruth, and social exclusion and terror, carried out under a cloak of pseudo-legality.

It was an honor and a pleasure to meet Iosef, now Yosef, Begun, who is still quite healthy and vigorous at the age of 87. When we failed to exhaust the subject of his adventures with the KGB in a single meeting in a conference room at the Jewish Community Relations Council in Manhattan, I invited him to meet me the next day at the banya in Brooklyn where I like to relax. His one major complaint about life in Israel, he said, is the impossibility of finding a good banya in that hot, Mediterranean country. He looked quite pleased, and accepted enthusiastically.

The flaw in our plan became apparent when we arrived at the banya. After asking Begun’s age, the banya owner blanched, and refused him admission. After all, he could suffer a heart attack and die right there in the steam room, and destroy his business. In America, he explained, there is such a thing as liability. The health inspectors could close him down.

Begun laughed. I pointed out that the man next to me, begging for his favor, had survived three Soviet prison sentences in Siberia. Who was he, a banya owner on Gravesend Neck Road, to deny an old man, who was also a great hero of the human struggle for freedom, his pleasure? If it wasn’t for this man, and others like him, I pointed out, you wouldn’t be living in America at all.

The banya owner was unmoved. Begun then pointed out that he had been to the banya in Moscow only a few months earlier, and he truly doubted that the banya here in Brooklyn would be anywhere near as hot. At this suggestion, the banya owner began to waver, torn between this proof of Begun’s fitness and the implication that his banya was perhaps not up to Moscow standards.

Eventually, we agreed that I would sign a piece of paper taking responsibility for Begun’s life. It was the least I could do, I thought, considering that through his actions, he had taken responsibility for the lives of millions of Soviet citizens, including members of my own family, and helped bring them to freedom. Plus, I was hungry for my morning tea and fruit. So I signed the paper.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversations, which were conducted in Russian-accented English with a sprinkling of Hebrew and Russian words and phrases, which I have translated back into Ruslish. I have allowed the banya owner a brief interjection in the middle to express his own feelings about the America he found.

***

David Samuels: I am so happy to finally meet you. You look even healthier than Mick Jagger!

Yosef Begun: He is a very healthy person!

So tell me, how did you become interested in learning the Hebrew language? You started studying Hebrew in the Soviet Union even before there was a refusnik movement.

The mass movement began just a little bit after the Six-Day War. But I began as you know in the beginning of the 1960s. “How” is a good question.

As a preschool child 5, 6 years old, I played with my friends in the yard, and sometimes they cried on me “Jew. Jew.”

Jew was just a very bad word. Very. I didn’t know what it meant. I am thinking, “I am like you. So why am I a Jew?” We fought, of course, and I was beaten.

And I came to my mom and I say, “Why I am Jew? Why they don’t like me?” That was the beginning.

There is a big interest now in this question: Who is a Jew?

My answer is, a Jew is a person who was beaten as a child for being a Jew.

When you asked your mother, “Why am I a Jew?” how did she answer?

She told me very simple things. She told me, “You know my son, yes we are Jewish. I am Jewish and your father is Jewish.”

What did your parents do? What were their occupations?

My parents were shtetl Jews. My father was a yeshiva boy before the Revolution. My mother was a Jewish girl who had a very small Jewish education in a heder for 24 girls. They moved to Moscow when Stalin became interested in industrialization, and there were many plants, factories. They came to Moscow in 1929 and my mother began to work in one of these plants. I was born in 1932.

Why did they move to Moscow?

They moved because I think [they were dealing with the] very problem of existence. Because shtetl was a problem with work, with food. My mother fortunately was a very dynamic person. As workers, they had an apartment with four other families. With one toilet, no bathroom, no bath. So, we began to live there, and to go to school.

The refusnik movement helped bring about the collapse of a totalitarian empire, without a single shot being fired. It was a great movement, like the movements led by Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., a movement which freed hundreds of millions of people and brought the planet back from the brink of nuclear war.

Yet today, the story of this great movement led by Russian Jews is nearly forgotten. Part of this forgetting is that that the Soviet Union collapsed, and then Putin created his own version of the Russian historical memory.

In Russia, everything now is return, return, back to Stalin. And they are lying about what was in Russia, including Jewish subjects, in serious books by historians, professors and so on. They say, “Everything was OK with Jews, they were scientists, they were musicians, wow, so many activities, so why are they complaining?”

But it’s all a lie. Because the real story of Jews in the Soviet Union was the attempt of the Soviets to eradicate us completely.

I say about myself that I am a survivor of two Holocausts. One, I am a survivor because my mother lived in Moscow and all our family in the shtetl was killed by the Nazis. Only I and my mother and father survived the war.

But during the spiritual Holocaust of Soviet Jews, I was part of a great movement.

Did your mother light candles at home, did your father say kiddush?

Nothing. Nothing. When I was born, it was 15 years after the Revolution. Maybe in some shtetls, people kept something. But in Moscow, it was a Soviet town. It was completely Russian, and there were very few Jews. Many newcomers in Moscow at the time were peasants from the villages. So anti-Semitism was something very meaningful. Jewish parents were afraid to tell their children anything. What they wanted, maybe for the safety of their children, was to keep them very far from anything Jewish, and to have Russian names.

Fortunately, I was given a Jewish name. But our life was a completely Soviet life. Any steps right or steps left, it was anti-Soviet and that was very, very dangerous. There was terrible fear.

Do you remember, as a child, the Nazi armies approaching Moscow?

Of course, I remember. I was 10, 9 years old. I was in a dacha near Moscow when it happened. I remember children running saying “War, war, war!” You know, like at play. I saw the tanks moved, immediately to the west, some planes, you know, so I remember the beginning of war.

Two or three months after that, my mother’s factory moved to Siberia and I went with my mother, and my older brother.

So that was your first time in Siberia?

It was my first time in Siberia, in Omsk. It was a very difficult time for us. My brother didn’t survive. He died of hunger.

Even though he was working in a factory?

He also worked, he was ready to go into the army. But he fell on the streets and died. And it was written: dystrophia. Do you know? Dystrophia means not enough food for your existence.

Do you remember when your parents found out what happened to their families in Belarus?

We knew when the war was finished at last. We knew that our relatives, they don’t exist. They were killed. They died, all of them.

Afterwards, military people began to return home and found that their wives and their children didn’t exist either. So we had an idea that everyone was killed.

How much did you know about the Holocaust, as an event specifically targeting Jews?

Well, we lived in a country with totalitarian propaganda. So we knew that the Soviet army made a great victory against Hitler’s army and put them out of our borders and liberated European people. Everywhere that army went, everyone was free. This we knew, and we were very proud.

But the truth about the Holocaust we didn’t know. We knew that all our relatives were killed. We knew that many peaceful Soviet people were killed by Nazis. No word about Jews.

In our shtetl in Minsk, in Belarussia, after the war had passed many years, the relatives who survived decided to do a memorial on the place of the Jewish mass grave with a five-pointed star, not a six-pointed star. A Soviet star. And it was written “here, Nazis killed many Soviet, peaceful people.” No word: “Jews.” And that time it was, everyone accepted that as reality because well, peaceful people were killed also.

But the Jews were killed because they were Jews.

So, you got a degree in radio engineering and statistics, and then you became interested in the Hebrew language. How did that happen?

Well, that’s also a very interesting point. Because it was not simple. Because all of you know the environment around me was anti-Jewish. Non-Jewish. And I was part of that. After my childhood and onward, I made acquaintance with the official discrimination, official anti-Semitism. There were quotas to go to school, which faculty you can be on, what institution. I felt it, but at that time, everyone just accepted it like something normal.

You know that Stalin sent the punished nations [away] and transported all of them. Even those who were soldiers during the war, with the medals and honors and all of that. So what happened with Jews, our personal problems with employment and so on, we accepted like something normal.

I went and had a very prestigious job, I became Ph.D. We were young and we enjoyed life, you know. And I liked the country where I lived. I didn’t know another country. And Russia is a beautiful country, in the sense of nature, and even culture. I liked it. I knew that I am a Jew, and that part was something not so good for me to demonstrate.

So I tried to be like all others. Despite the fact that when you are coming to find a job, they also knew because it was written “Jew” in my internal passport. It was line five on the passport.

In addition to all of this, I was a radio engineer and I worked in a so-called closed institution, a research institution for military purposes, for radar.

My first memory of feeling something else was the youth festival of 1957. Delegations came from different countries of what they called progressive youth. Even from Israel they came. But the Soviets did everything to prevent meetings of Soviet Jews with these delegates. I was afraid to even approach anyone because the entire atmosphere was anti-Jewish, and because I worked in a closed institution.

You could be a traitor who was handing over military secrets.

Of course. We were instructed not to visit places in Moscow where foreign tourists are going. Restaurants and so on. I was afraid even to communicate with Israelis. It was in ’57. I was at the time 25 years old. Then, in the early ’60s, I began to study Hebrew.

Why? How? I am trying to imagine you at that time. You live in a closed society, and everyone is told you must obey, you can’t say anything or we will punish you, so everyone continues to stand in line. But then for some reason one person—and this person is you—he says, “I’m going to step out of line.”

Why you? You had a perfectly good Soviet life.

First of all, it begins inside. It begins in your brain, in your conscience, and so on. I was a Jew. I was embarrassed. I tried to hide my Jewishness, and even when I make some connections with some girl for example, or other young people, I did not tell them that I was a Jew. But then something happened.

What happened? I liked to watch movies.

Huh? Explain that.

I am a movie madman. A fanatic. I like movies. And at that time, after Khrushchev’s policy of the so-called thaw, with the international festival and so on, you had musicians coming, an international exhibition coming from France, and so on. And foreign movies began to screen in the Moscow cinema.

And in these movies, there were episodes of Holocaust. Episodes of Jewish killing. Massacres, in French, or Italian, or Polish movies about the war. About also what happened in Poland, not about Jews but partisans. In France, some very interesting movies, with very famous actors and so on and so on. And sometimes you saw scenes representing the Holocaust, some crowd of Jews being gathered together and put on trains.

I remember one very famous movie called The Shop on the Main Street. A Czechoslovakian movie. It was in ’65. And it was a very famous movie because, well it was really about the Jewish subject completely. And the actress was Polish, Ida Kaminska. A very famous Polish actress, and Jewish.

When I began to watch such episodes of such movies, something moved me, you know? I began to feel some identity with people who were persecuted. I saw these people, Jews. I am a Jew, they are Jewish. If I was there, I would have shared their fate. I began to recognize my identity, my belonging to the Jewish people.

Before that, I was really alone completely. I felt alone in a crowd of people. My friends, my colleagues at work. Millions of Jews lived in such way in Soviet times.

But when I saw those movies, I got some other feelings. I am one of them. I realized that it was a terrible Soviet policy, to completely destroy the Jewish people by depriving us of all knowledge about who you are, about your people, about the history, about your tragedy, your ancient history, your modern history. Israel, it was a terrible country, imperialistic, aggressive and so on. People were afraid to talk about any of this. And then I saw that I was among these people. I had identity. It was mine.

What led you to Hebrew language?

I was an educated person. I lived in a cultural environment in Moscow and so on. So I of course began to ask: What does it mean? I would like to just read. But in Moscow there were no books.

So I came to Soviet Great Library, the Lenin Library, the greatest in the world, they say. But there are no Jewish books available. They had removed them all.

But just at that time, they began to publish some Yiddish books in a Yiddish-language magazine called Sovietshe Hemlen. Sovietska Homeland. I understand that it’s a Soviet magazine of course, but in any case, it’s Jewish, about Jewish books. And I think, OK, I will learn Yiddish, so I could read this magazine.

And that was the time that I made some acquaintances, some much older people than me. Khrushchev permitted some Jewish singers to make some concerts. Michael Malefshitz came from Vilnius, in the concert hall in Moscow called Tchaikovsky, if you know it. And many Jews of course ran there to hear their music. And my mother went there also.

Did you go to the concert?

Yes, with my mother. Yiddish was her language. But she didn’t teach me. But she was happy to listen to Jewish songs. And I saw many older people. Jewish people who were talking Yiddish.

Now I think, OK, if I learn Yiddish, and I can read this magazine, I can talk with these people.

Did you have the sense that what you were doing was a dangerous or subversive activity?

No. Yiddish was officially permitted. But very soon I realized that it’s impossible to learn it. And then something happened that changed my life completely.

I met a person, among all these old people, one of them, and I began to talk with him, by chance. I told him that I would like to learn Yiddish, but I couldn’t find a textbook or even a grammar. I had learned Dutch, I learned English, but Yiddish I could not learn.

So he asked me, would you like to learn Hebrew? Hebrew—I asked him—what does it mean Hebrew? He said to me, you know it is the language of the Bible. I asked him, What it is Bible?

He tells me. Then he tells Hebrew is the language of State of Israel.

Because of my curiosity I think, OK, I try. It’s interesting, maybe I’ll talk with him about that. So he became my first teacher. I called him my first teacher with capital letters: First Teacher. He was my first teacher of Hebrew, and my first teacher of Yiddish a little bit.

But who was he?

He was an old man. He had been a student at the Volozhin Yeshiva before the Revolution. He lived in a small, poor flat, but he was a very educated man. He told me that he had met Jabotinsky. He was really very interesting.

What was your teacher’s name?

Lev Guryevich.

At your work, anywhere else, did anyone ask you, why do you have this strange hobby? What does it mean?

Nobody knew. It was my secret. I studied with him in a very secret way.

For how long?

It was some period of time. Until the Six-Day War, until the beginning of my approach to Zionism.

So, before the Six-Day War, it was just you and this one man, for many years?

Yes.

Sitting by yourself.

I made my secret visits to his very shabby room where he lived with his neighbors.

Once a month? Once a week?

In the beginning, maybe it was once a week. After then, maybe once a month. But we became friends. We became good friends. And I tell it a lot about him in my book. About his death, about everything. Then in 1968 I joined a half-underground, Zionistic group in Moscow.

How did you come in contact with them?

I told you that I was, in private, secret ways, meeting with my Hebrew teacher. And I worked in this secret institution as a research worker. There, I made some connection to do some additional teaching after my main job for some group of students, to make money. In this factory, there was a group of people who wanted to begin studying in university, and they needed to know some knowledge about math.

So I made some acquaintance with a person who was also a teacher of math. And he was Jewish, and we became friends. And our place of work was a little bit out of Moscow. And we would even come together to Moscow by bus, but we were talking about different things, but not about Jewish subjects. I stressed it because to talk about Jewish subjects was not accepted, and was even dangerous. I was afraid, and everyone was afraid, to talk about such subjects.

Now this guy was also a Ph.D. and so on, and his hobby was Esperanto.

Esperanto?

The Esperanto language. And he was very often inviting me to join his company of people who were interested in Esperanto, learning classical literature in Esperanto, very interesting people come there, and so on. And all the time I would say, “You know I am very busy, no time, it’s family, work.” But we returned home after our lectures, he began again to talk about this and he saw in my pocket a small textbook of Hebrew that my teacher gave me. I called him Mori. You know Mori means my teacher in Hebrew. He made me that book.

Then the man on the bus began to talk with me in Hebrew. And of course, it happens that his Esperanto group was actually a Zionist group.

So of course I came with him to his group of Esperanto Zionists. And from this moment I became a Zionist, and I met people who lived by their hope to go to Israel.

There were number of such groups in Moscow. The leader of this group was David Huftan. We Russians all knew about him. There was some idea to call some kind of street in Jerusalem after him, but for now it’s not decided. It was a real Zionistic group.

And how many people were in the group?

It was not many people. It was such an informal group. We made some picnics in nature, in the forests, with Jewish songs, with guitars. They really lived, like all of the refuseniks started to live for some years when this movement began, with the Jewish holidays, Hebrew language, connections with Israel. And they sent their appeal to go to Israel, were denied, and became refuseniks.

***

We resumed our conversation the next day at the banya on Gravesend Neck Road, stopping to talk with the banya owner.

Banya Owner: When I started here, it was admission $3. In 1980. But I had only one sauna. Outside I made shish kebob, I sold Coca-Cola or Sprite, that’s it that’s what my money was. At the same time, I was a property manager for some real estate.

Because we came from Russia, we were hungry for—not only for work, but for freedom. When you put your mind and your soul in your hands, and bring it to the right place, you can do a lot of things, right? But now what they are doing in United States, I’m sorry.

David Samuels: Yeah, America is a big mess these days, with the division between Trump and anti-Trump.

It’s very bad. They need to kiss this ground before they say something. Schumer and Pelosi didn’t vote for Trump, OK. So what? The American people voted for him. They have to respect our choice. But they don’t respect us. So how they can be in Congress?

The elite of this country has become very arrogant. They believe that it is their right to rule the rest of us.

The colleges are very bad. Very bad! The professors, I would hang them. I would hang all of them! Because it’s crazy to listen, even. And they think that we don’t understand what we are talking about. Why do I have to pay taxes, you pay taxes, and they come, thousands of people, coming across the border daily, and they are getting everything for free?

And this idiot Sanders says we should have socialism now in America.

The last question: Why do people want to come here?

Everyone can listen to bullshit in their own country.

Not for the bullshit! Yes. That’s correct. I am an immigrant. I respect all immigrants. I have a couple of Mexicans, and they work their asses off, and I pay them good money. But good people, let them go through immigration, like I did, and like he [Yosef Begun] did. We were sitting in Italy and Austria, sitting there and waiting until the United States government gave me a piece of paper and I could come here. In a year I got my green card and in five years I got my passport. I respect and I kiss this ground in the morning. And before I go to sleep, I kiss this ground again.

But look at what’s happened in America in these last 25 years. You have these huge technology companies that are each worth hundreds of billions of dollars. The individuals who own those companies are worth tens of billions of dollars. They pay no taxes, they keep their money outside the United States, and they’re the ones who are pumping this propaganda into everyone’s head. Social justice, anti-Trump, pro-Trump, it doesn’t matter. The point of everything is to preserve the fortunes of the oligarchs.

You know what exactly the sickness is. It’s wrong. I just was in Florida, I spoke to a guy, he was working as a mechanic in a big factory, I think Chrysler in Detroit, and he came to Florida, he retired and everything. And my wife and I, we listen to Fox News, and we invited them to visit for tea, coffee, whatever. He asks me, why are you watching this Fox? I say I’m sorry, I put on ESPN, forget about it. They are brainwashed so much that they don’t listen, they do not analyze.

Everyone can choose their own propaganda. But freedom is something you have to cultivate in your own mind.

Yes. You have to work at it. I grew up in this area, Sheepshead Bay, Manhattan Beach, that’s where my business started as a property manager. I have 17 buildings, 128 apartments. In Manhattan I have about five, six buildings. 150 Broadway. You can’t imagine. I was coming in a black tie to check the building. Thanks to Michael Newman [the property owner], let him rest in peace.

He tells me, you have to learn English. You came to the United States, you have to learn English. What do I have to do? He says, take a dictionary, take a newspaper, and he brings me the New York Post. I read it quietly. I read, then I don’t understand one two words, and I find translation and I have to explain him in English what this means. I was a good student to him.

God Bless America.

When we celebrate with my friends, we sit down, first we toast, God Bless America, and then the rest—Happy birthday, Mazel tov and everything else.

Yosef Begun: America is the best country. Am I right?

Banya Owner: Yes. A thousand times, a million times. It’s just that people don’t appreciate that now, they don’t understand.

At that point, the banya owner left the conversation.

David Samuels: So, tell me about the Esperanto club in Moscow. Did they meet in an apartment?

Yosef Begun: An apartment yes, it was in an apartment. It was, north of Moscow. I don’t remember if it was communal apartment or maybe private apartment, I don’t remember exactly.

And so now you are no longer alone. You are part of a little world of people.

They all lived with a dream to go to Israel. It was their idea. Main idea. And because they could not go there, they began to do everything, to be, to live and be Jewish here, in Soviet Union, despite the fact that there were no means to be Jewish.

First of all, Jews were separated from each other. It was an atomized society. There was no place where Jews could meet.

Where would you go, besides the apartment?

Sometimes we would go to some forest, like a group of tourists, find a place, sit down, and talk, and everything in an open way in that place. And when you find company and feel that it’s your company, it’s a very good time for you.

It was something very unusual. This was real Jewish community. There were many groups like mine. And sometimes we met, but everyone just kept their own company and celebrated holidays together. And when you enter to this company, it couldn’t be such a great conspiracy.

People of authority in socialism were completely quiet toward Jews because it’s a time of social detente. So Jews became more courageous. But of course we couldn’t demonstrate on the streets and the parks, because the KGB was watching.

When was the first time the KGB came to you and said, we know you’re involved in these activities, be careful, stop it.

I remember it was 1972, and it was [around the time of the] first visit of the president of America to the Soviet Union.

Nixon came to Brezhnev. And of course the authorities became strict, you know. I lived on the first floor, so the I would see their car. KGB car. A black Volga. I understood that Nixon was coming so they were watching and looking at us. If you went out of your home, you immediately saw that they began to follow you.

There was such a procedure that you had to take trash from your home and go two blocks to throw it. They were following you. So they followed me to the trash. So it was just: Play with the KGB.

But you know what? This visit of Nixon was very interesting because you know what happened? It was my first time arrested. Not real arrest, but I was taken and put in prison. They were very afraid of some demonstration, so they cleaned Moscow. For us Jews, we were in delicate situation, because we had support from abroad, and they knew it. So they noticed us in a more delicate way.

The day Nixon came, they came to my home, 6 o’clock in the morning, I was sleeping. Ah well, you want to follow us? We will bring you to the police station, they would like to talk with you. Something like this. I lived with my mother at the time, she said, “Why? What’s happened? What? He didn’t do anything. Why you are taking him?” “OK Mama, be quiet, I will be back in an hour maybe.”

They didn’t even bring me to the police station. We drove out of Moscow and I saw 50 kilometers, 70 kilometers, 100 kilometers, some small town near Moscow. And they come to the prison, small prison in a small town. And I was brought there, myself and another two people. They picked up people from our group and brought us to this prison, and we were there for 10 days.

When we got out, when they said, OK you are free, not free, just go out yourself because car was waiting for us, for everyone a special car. And I asked them, give me papers that you kept me here. I am a working man. I will be fired because I did not go to my workplace. They said, no, we have no papers for you.

So they brought me home, but the next day I went to my local police station and I said, “OK. I was taken by people from the KGB. Give me something for my job for my boss.” He said, “I didn’t do anything.” Very rude policeman, you know he said, “No, get out of here.” It was my first experience like that.

This was repeated several times. The separation and arrest after Nixon. They practice this. I lost my job. It was very difficult. But I had to do it.

And that was when I decided that I am Hebrew teacher. My students pay me. Two, one rubles for a lesson, and during the month I have 100 rubles and this money was small but solid. So I am not a parasite. I have an occupation and an income from that.

And I wrote them a letter. Either you can give me my professional job—I am electronic engineer and I prefer working; I am sure that you need such a worker. Or you can just accept my working as Hebrew teacher, and recognize that as my profession.

Was this stubbornness a natural part of your character? Or did it develop this way over time?

When you begin to play with them, you get less afraid of them. Because I knew that I am right. Then what they were doing was not legal, not according to the law, not according to the constitution. They were above the Russian people and the law. The Russians are led by people, not law.

So because of this, I became more and more brave.

You understood that you had power.

Yes, you are right. Because for them, you know, when I became so important, dissident—to them, Jew—my point was culture. Language. My point was Jewish identity. They destroyed it. I tried to recover it. But for the Soviet Union, it’s an empire. It’s many, many, many nations that they treated this way. They very cruelly destroyed all these nationalistic movements, so that the people became Soviet people

And how did you learn that history? It obviously wasn’t in any book.

I began to realize it much more later, when I became real participant in the movement. But before when I was just alone, I did not think a lot about this. I just would like to become Jewish, to know more about myself, about my people, my history and so on. It was very important to me.

Just take the Holocaust, for example. As a Jew, I understood that it could be my fate, too.

As it became clear that the Soviet state was going to be in a war with these dissidents and refuseniks, was your focus on changing the Soviet Union? Protecting Jews? Or was it: I want to get out of here and go to Israel?

We Moscovites, we knew what was forbidden. So, you begin with your discomfort with staying in a society where this is forbidden, that is forbidden. You can’t go out of the country, you can’t read this, you can’t listen to such-and-such music, you can’t read this book.

A big part of society, especially intelligent people, they understood what country they live in. I understood. And they of course they hate regime. But they were afraid to do something. They lived inside and they listened to Voice of America and sometimes in the kitchen you talk with your family or with your friends. Some of the people were afraid to read samizdat, because it could be very bad if you were caught.

And there were people who were maybe more intelligent and maybe feel it most strongly. They became the so-called dissidents. And I was with them first time, and we were distributing chapters of the novels of Solzhenitsyn and some other stories by other writers. And it was very interesting work. We distributed, hand to hand, copies of those books.

After that, I became more interested in the Jewish subject, so I became just a Jewish activist, after the Six-Day War.

When would you say that leaving the country became your goal?

When I realized my Jewish mission for myself, personally. I was a little bit more advanced maybe, than many others.

Each may be interested just to leave country. Because to live here was very unpleasant, yes. But for me it began more and more to become an interest to join myself to the culture, to all these treasures of the spiritual Jewish inheritance.

Inheritance. It’s funny, every human being is different, and extraordinary people are especially different from each other. But when I talked to [Natan] Sharansky, you can hear Zionism, Zionism, Israel. The Jewish stuff, in the sense of religion and culture, came from his wife. When he came to Israel, he understood that there was actually a broader cultural base than just Zionist nationalism. For you, it almost seems like the reverse.

I didn’t know a lot about Zionism itself. It was also closed from history for us.

Did you read Exodus in samizdat?

I read Exodus, yeah, of course. You know what I read, I read Exodus. But Hebrew study was an interest in itself. You understand that it’s not one new language.

I’m so curious coming from a Soviet mind, and you open the Bible, and you read about a big flood, or Abraham sacrificing Isaac. How did you even understand what is in this book? What are these stories? Are they beautiful? Are they crazy? Is this a children’s book?

It’s very simple because you know, Russian education wasn’t so bad. They did try to educate the people. First of all, we knew the history of Russia. We know how Russia became Christian. So we knew, if there is a nation, they have history. They have culture. They have myths, yes? So, this was a book of the history and myths of the Jewish people.

Right. That makes sense.

Now, the first thing an authoritarian state tries to do is to cultivate informers in any movement that might threaten state power. And the second is to make the movement paranoid about informers, because that way you could split them very easily. Was that something that was a major drama in those times: Is this person an informer, is this person an informer?

First of all, our network was not so close. We kept it open. For example, we claimed that we are Hebrew teachers. We asked the authorities to accept our profession. We demanded literature for Hebrew, because it’s our native language and so on. So it was very open and public. We didn’t want to overthrow the government.

Let us leave the country. Otherwise, we learn our language. That’s it. No anti-Soviet propaganda.

We of course understood that among us there are the people who are telling them everything. That was especially clear when Sharansky was arrested. These people appeared and said he said that, he said that, what Sharansky did. These included people who were in a very good position among our society. People loved them. One of them was a doctor, a physician, who treated our people. And he was very helpful to many people, and people loved him. He happened to be KGB.

But Sharansky connected with foreigners, engaged in correspondence, and other officially illegal acts. Most of our activities were done in an open way. And the authorities knew everything about us.

You just accepted that they knew everything.

Yes. They knew everything, and we knew this.

There were of course some specific things, for example, if you wanted to write some letter to draw some appeal and to send it maybe to an American senator or some such operation. And of course you wanted to send it, but not to be taken by KGB. So this work we made it more secretly.

In my book there is a story that’s interesting. Maybe you have heard, there was such, in ’76, it was called Symposium of Jewish Culture. Professor Benjamin Fine. He was a charming, very smart guy. There were some other people and they joined us in this movement and actions. The idea was to gather people who were really interested in the state of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union, and just discuss this question. Perspectives on the state of Jewish culture.

I assume for the government, culture is the one thing they can’t protect against, right? Sharansky is a bad guy.

Yeah, yeah. He is spy.

But you just want to study the Hebrew language and Jewish culture.

Exactly.

So we prepared this symposium in a very open way. First of all, we would publish such a paper. We invited the chief rabbi of Moscow—“chief rabbi of Moscow”—academic specialists in culture, and such scientists from literature and the traditions of nations, and we said that we would like to discuss meaning of culture and state of Jewish culture of this moment and paint a picture for the future.

The KGB was very, very excited about this event. They immediately began to do search, they came to apartments and took hundreds and hundreds of books and manuscripts, everything connected to any Jewish subject. I have in my book a long list of confiscated items. For example, among them, a book titled Pogrom in Bialystok in 1907.

The KGB people came to apartments, they didn’t know English or any other language, so they said, “Oh, Magen David. Let’s confiscate.”

Right.

We began these activities in April of ’76, and we set a day for the symposium: 25th of December. Many people began to write papers, reports for the symposium. And there were written 50 reports. I wrote about the importance of culture for the existence of national minorities, and so on. And KGB tried to take all of those reports. They followed people, they got into apartments, confiscate, confiscate, confiscate.

Then they arrested 17 people, including me. They brought me to the police station. I was sitting there a full day. They finished the accusation, they said, OK. And I was told, tomorrow if you go out of your home tomorrow, you will be taken again.

So I stayed at home the next three days, and the symposium was planned for four days. It was home arrest for the main organizers. 17 people. So the symposium was shut down.

Then began 1977, a new year. That year was very, very not good for dissidents and for Jews. I was arrested in March. The Helsinki group was shut down, and people were arrested. It was clear that the KGB began to squeeze this movement, using greater resources and more force. So I think, maybe our symposium was more important than I thought.

Right.

So we decided in a very, very secret way, with professor Fine and me, we had to go to the American Embassy and bring them reports of the symposium to send this abroad.

This operation was in such a way. I was given copies of half these documents. And we had to meet with Fine near the American Embassy, and he would have the other half. I was given these docs, in a very secret way. To go to the American Embassy, not to be caught with it. And the next day I had to meet Fine, and we would bring in the report together.

And from that moment, when I took these docs, I realized that I [was being] followed by the KGB. It was strange for me because everything was made in a very secret way. It was just Courage Day [a state holiday geared to children], and there were some children’s event, and many people came with their children. And in that moment, at one of these events, one fellow gave me a bag, he said I should not open it.

I took his bag. I was in a crowd of people, with teachers, and my son. But when I left the school, I immediately saw people following me. I tried to shake them off, but it was impossible. They followed me exactly a meter behind.

When I realized that I was being followed by these people, I understood that they could take me any moment, and take the reports. So I thought of some plan. I would leave it in some place which was not suspicious for the KGB, in the apartment of my friend.

So I came to her home. Like one friend come to another friend. And see her, nu, OK. Can you keep this pile of papers until tomorrow? OK you can leave it.

I left it there, went out of her home, and after then, they began to follow me.

Did you leave her home with the bag?

I went out of her home with my bag, but I left the documents with her, and I put some of her books instead. And when I went out of there, they were following me. They were in a group. Not one, but three, four or more people. And they did not even give me two meters of space.

Now when I went maybe 100, 200 meters, I realized, they are gone. I said, Woah. I don’t know what’s happened, but I am free. I checked, I checked, I checked, but they were not after me anymore.

So I went to another friend’s to sleep, not go home. Because I was afraid that they could wake me at my home, they could take me. But tomorrow I have to go to the American Embassy. I slept, and in the morning time I came to this home where I left the documents, it was not far from the American Embassy. No one followed me. There, I took my docs and put them in my portfolio, and went back outside.

And when I moved to maybe 15 meters out of this building, I realized that all these guys were following me again. But it was time. I had to go to the Embassy. And right there I went to meet Fine, 100 meters out of the Embassy, in Red Square. And I came there, and Fine was there.

And I told him, they are following me. And he said OK, OK, give me your portfolio. I gave him my portfolio with documents. So we went together and a big crowd of these people followed us. And I realize that some of them are following him, and some were following me, and now they have united behind us.

Now, when we met with Fine in this square before, he, Fine, had some previous talk with some American person from the Embassy, and he came to the place to meet us. So when we went to the Embassy, to the entrance, we were three. Fine, me, and the American guy.

When we were very close to Embassy, one of the KGB guys who were following us went in front of us. And he went up to the entrance of the American Embassy, said some words to the Soviet guard there, and they closed way for us.

And this American guy said, What’s happened? They are my friends. And one of them says, “They are no friends, they are criminals.” In English to the American. Two black cars immediately came, and we began to cry, “Why are you taking us?”

They brought us to the trucks, took us to some police station. Of course, they took the reports.

So the operation of the KGB very successful. They followed us, they stopped us, and they took what they wanted. They prevented our entrance to the Embassy. It was my first actual arrest.

Now I ask you: How do they know what was inside my portfolio? If you follow my story, they knew from the very moment whether I had the papers inside or not. It is a puzzle, right?

What’s your answer to the puzzle?

The answer to the puzzle is an isotope. They have a very special receiver which receives radio waves.

You know these people that followed me, they included some guys with a portfolio. I didn’t pay attention especially, but the man with the portfolio was very close to me all the time. In his portfolio was the receiver. The receiver told him that something containing the isotope was inside my portfolio or not.

So among the typists who produced such materials for you, someone was working for them, and they put the isotope onto the paper.

It’s one hypothesis. But who knows. It’s a puzzle.

Who was the courier who brought you your half of the manuscript.

OK, I could say his name, a refusenik Nagila Prestin. He gave me this portion. But he got it from maybe some other people.

Just to finish my special story: This is a story that was published in samizdat. It is a story about Lithuania. In Lithuania, there were also there were some dissidents, who were of course nationalistic. And they distributed a big amount of educational material for people. And the KGB was very concerned about this because it was printed on a machine. Like at a publishing house. And they tried to understand how to find this machine. Some place, some home, some apartment. They looked, they looked, but they couldn’t find.

Now, they knew that to publish such a big amount of material, you needed a lot of paper of a certain kind. A big block of paper. This paper was sent to Lithuania from some factory. So they took the paper, and they put in the same isotopes.

That’s great. Now we will trace your paper and see where the printing press is. Because you will store the paper next to the printing press.

Yes. They used a helicopter. A helicopter traced all of the republic for the radio signature of the isotope, and they found the printing press and this large block of paper in a small hut in the forest. So they came there, and confiscated the paper and the printing press.

I imagine that they fed some similar type of paper into our system, and let us type everything up, so they could trace it.

That’s a great story. And now we have to go to the steam room. Because otherwise I’ll feel guilty thinking of you, a hero of the human struggle for freedom, who spent so many years in the cold in Siberia, living in Israel without access to a decent banya.

***

Happy New Year from Tablet magazine. You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.