Spirited Away

His masked hero has arrived on the big screen, but it’s Will Eisner’s slice-of-life comics that loom large

Let me begin with a confession: I’m not a fan of The Spirit. Will Eisner’s 1940s-era crimefighter, who last week became the latest comic book icon to make the jump to the big screen, has never particularly moved me; I find him contrived, not quite believable—more a pastiche of a hero than one fully realized on his own terms.

The Spirit’s significance has more to do with what it led to than with what it was. Eisner, who died in 2005 at the age of 87, published the comic from 1940 to 1952 as a Sunday newspaper supplement, which—because he operated as an independent contractor rather than a work-for-hire craftsman—allowed him a degree of creative control and ownership that contemporaries like Bob Kane (the creator of Batman) or Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (who developed Superman) never had. He could be ambitious, trying out odd narrative devices: “The Last Trolley” takes place in its entirety on a late-night streetcar ride, while “The Killer” unfolds (at times literally) through a murderer’s eyes.

The idea was to introduce comics to a more mainstream, adult audience. “I wanted to write better things than superheroes,” Eisner said in a 1997 interview, discussing both the origins of The Spirit and his desire to transcend genre limitations from the start. “Comic books were a ghetto. . . .[The newspapers] wanted a heroic character, a costumed character. They asked me if he’d have a costume. And I put a mask on him and said, ‘Yes, he has a costume!’” On occasion, the Spirit himself became a peripheral character in his own series, as in “The Story of Gerhard Shnobble,” where the crimefighting occurs almost entirely in the background of the main plot, which involves a man’s slow, inexorable passage to suicide.

Yet if all this speaks to the influence of The Spirit—you can do almost anything in a seven-page comic, Eisner seems to be saying, a radical notion in the 1940s—I’ve long had the feeling that he continued to chafe at the conventions of the medium, that he couldn’t quite align his aspirations with what were, after all, irreconcilable restrictions: the need to resolve everything quickly and neatly; the crimefighter template, with its palette of cops and criminals, heroes and femmes fatales; the throwaway nature of comics in general, which even into the 1970s were regarded as a disposable form. It took a quarter century or so for him to come up with a solution: the long-form comic, or graphic novel, which Eisner helped innovate with his 1978 book A Contract with God.

Three decades later, it’s common to claim A Contract with God as the first graphic novel, but like all creation myths, this is not completely true. In the first place, the book is not really a novel, since it doesn’t tell a single story like the literary works Eisner aimed to emulate; it contains four long stories of Depression-era Jewish life. More to the point, as Eisner himself acknowledged in a preface to the 2005 omnibus The Contract of God Trilogy, he was less a pure innovator than part of a continuum, influenced by experimental graphic artists who in the 1930s “produced serious novels told in art without text.” These are the so-called woodcut novels, inspired by expressionism and printmaking and conceived as a response to silent film. It’s hard to call them comics, exactly, although you can see the work of certain comics artists (Eric Drooker; Peter Kuper; even, to an extent, Art Spiegelman) in them. Yet what their existence suggests is that, as Spiegelman puts it, long before A Contract with God, “the idea of a long comic book was in the air . . . There was conversation about it, and there was even an attempt to figure out what it might be.”

What, then, is Eisner’s real legacy, 30 years after A Contract with God? More than anything, it’s that he recognized the potential of the medium, seeing in comics not just disposable juvenile entertainment but a storytelling palette as rich as that of any narrative art. This is what The Spirit, at its best, has to offer, although it came to fruition only once Eisner shifted his focus—in A Contract with God, as well as the dozens of other graphic novels he produced, at the rate of nearly one a year—to the material he knew best: the urban immigrant world from which he had come.

Here, we have the landscape of A Contract with God: a tenement in a neighborhood of tenements, populated equally by the dissatisfied and the dreamers, by the betrayers and those who feel themselves betrayed. The title story revolves around Frimme Hersh, a Hasid who walks away from religion after the death of his daughter, which he deems a violation of the covenant between God and man. That’s an audacious way to start a book, especially a comic; it announces Eisner’s ambition in no uncertain terms. Comics, he wants us to understand, can take on the most elusive subjects: spirituality and religion, death, obligation, and all those messy questions about existence—about who and what we are.

At the same time, his characters have no choice but to play out their own small dramas, the minor-key struggles of the everyday. This slice-of-life approach is reminiscent of Daniel Fuchs, whose Brooklyn novels of the 1930s—especially Summer in Williamsburg and Homage to Blenholt—also take place in the Jewish tenement, with its strivers and its shnorrers, its sense of community as a comfort but also a burden, where people are always in each other’s business and everyone is looking for a way out. That’s a point driven home by the final image in A Contract with God, in which a young man named Willie (an Eisner stand-in) watches the sunset from a fire escape, turning his back on his mother, who warns that “[t]his year you’re going to have lotsa responsibility around here.”

Eisner’s thematic similarity with Fuchs offers one approach to understanding him—as aligned with, if not exactly part of, the tradition of Jewish immigrant literature. Even so, he remained very much a product of his medium, which was undergoing an evolution of its own. It’s telling that even as Eisner was developing A Contract with God, underground artists like Spiegelman and Harvey Pekar were mining not unrelated territory; the former’s first short “Maus” strip appeared in 1972, as did “Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” which exposed his torment at his mother’s suicide, while the latter’s “American Splendor” series debuted in 1976, raising the slice-of-life aesthetic to high art. These works, of course, were not widely distributed; they caught on by word-of-mouth. Still, it all suggests a certain nascent sensibility, a self-consciousness about comics that was transfiguring the way a lot of people, both in the underground and the mainstream, were thinking.

In 1978, the year A Contract with God came out, Spiegelman published the original Breakdowns, a collection of his shorter, edgier work from the early 1970s, including both “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” and that early “Maus.” (It was republished with additional material in 2008.) “What I needed at the time,” he said in an interview with me early this fall, “was to see it all together . . . to see what it added up to on its own.” As a statement of intention, it’s remarkably of a piece with Eisner’s aspirations for the graphic novel: “My early work in newspaper comics and comic books allowed me to entertain millions of readers weekly, but I always felt there was more to say,” he wrote in The Contract of God Trilogy. “I yearned to do still more with the medium. . . . Call me, if you will, a graphic witness reporting on life, death, heartbreak, and the never-ending struggle to prevail . . . or at least to survive.”

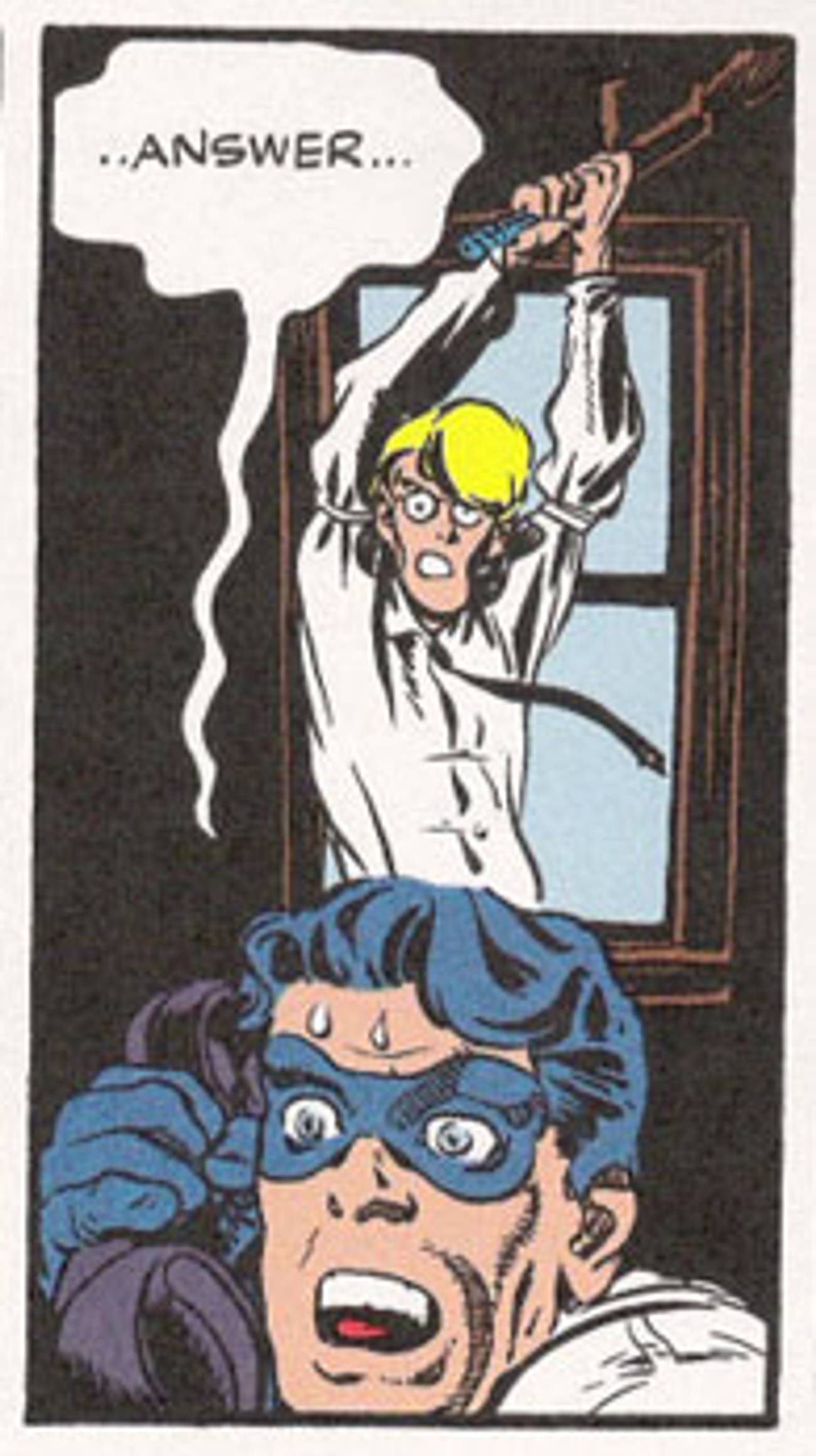

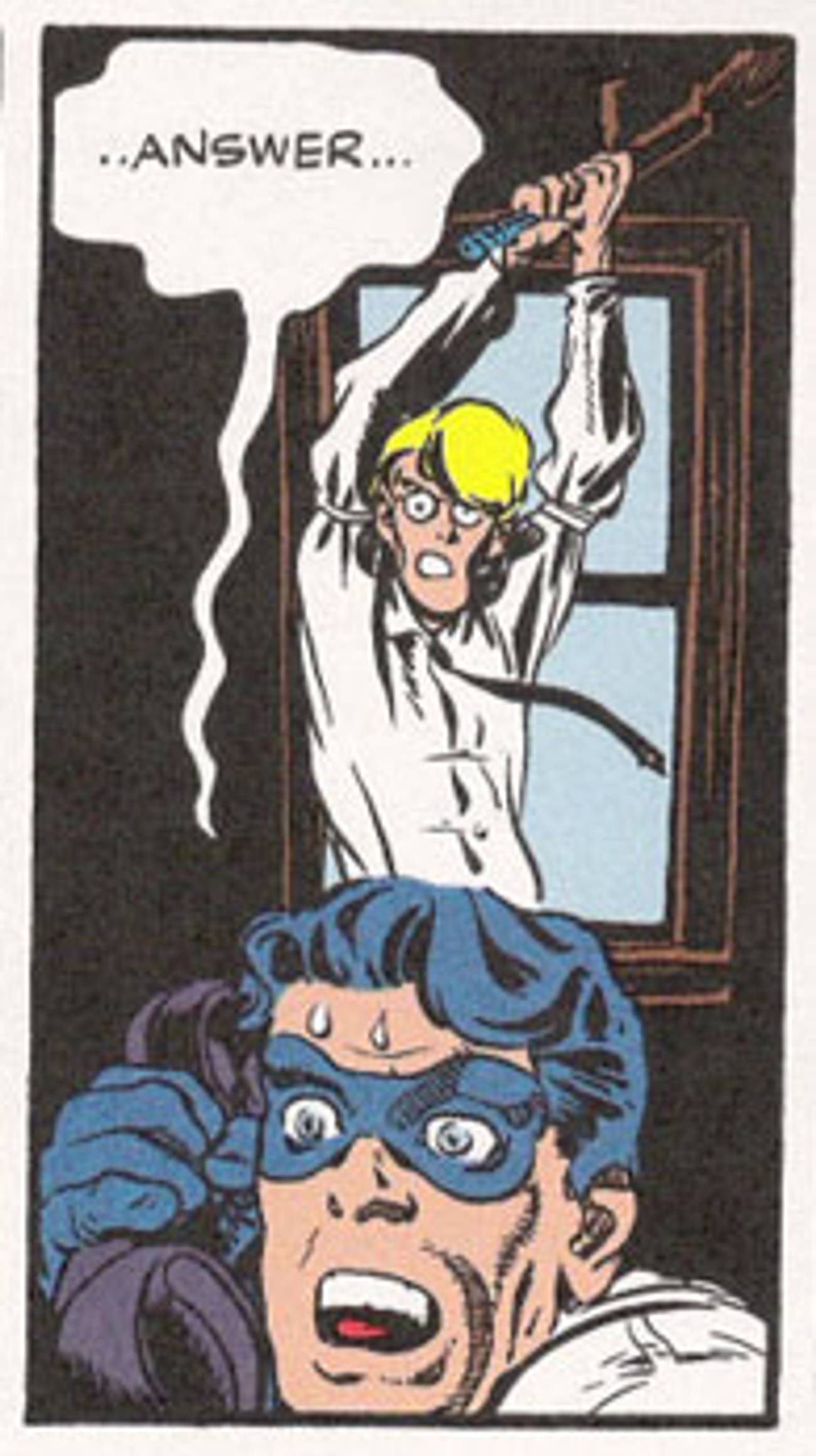

And yet, if such a comment indicates the extent of Eisner’s achievement, it highlights something of his limitations as well. Try as he might, he never quite overcame the comic-book sensibility of the 1940s: a broad-strokes approach to both text and image that often lacked the subtlety necessary to convey complex subjects. His drawing style could be imprecise, sweeping, with melodramatic action sequences that were all on the surface and left no room for sensitivity or depth. His narrative abilities were inconsistent; for every sequence like the one at the beginning of his 1988 book A Life Force, in which a man named Jacob Shtarkah reflects on the meaninglessness of his own existence by ruminating on a cockroach in the alley (“So?? Mister Cockroach,” he asks, not quite rhetorically. “What are you struggling for?? To maybe stay alive a few more days?”), there are other efforts that come off as gimmicks, mawkish, or too easily resolved.

In “The Super”—the third piece in A Contract with God—a simple man is tricked by a conniving schoolgirl who steals his money, and Eisner uses this as the setup for an overblown, if tragic, ending. “A Sunset in Sunshine City,” written in the 1980s and collected in the Will Eisner Reader, opens with a deft evocation of an elderly cafeteria owner’s nearly physical sense of memory but quickly yields to a predictable saga of retirement and aging—the character forgoes his neighborhood to move to Florida, where he ends up spiritually and emotionally lost. Even The Dreamer, a 1986 autobiographical “novella” about the early days of comics, comes to us almost devoid of conflict, with the nuance and uncertainty flattened out. “I’ve got a big future,” Eisner’s alter ego announces late in the story. “I know mine will come true! . . . It’s hard to explain . . . but I know, I know!”

It’s unimaginable that Spiegelman or Pekar would ever traffic in such overt sentimentality. Nor, for that matter, would any of the contemporary comics artists (Alison Bechdel, Adrian Tomine, Ben Katchor, Daniel Clowes) who might legitimately be called Eisner’s heirs. Comics are too sophisticated now, too complex: we come to them with an entirely different set of expectations than we could have 30, even 20, years ago.

Yet this is only as it should be, a sign of the cultural shift Eisner helped to bring about. He was a man of his moment, who recognized that comics were capable of storytelling in all its diversity and depth. He was an essential bridge figure, a survivor from the early days of the medium, who lived to see the graphic novel institutionalized in both an aesthetic and a commercial sense. And he never stopped trying to push boundaries, as he had throughout much of his career.

In his final book, The Plot, completed only a month before his death, Eisner tried once again to take comics in a new direction by telling the story of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the fraudulent tract, supposedly outlining a Jewish plan for world domination, that anti-Semites have used for more than a century to justify everything from pogroms to Nazism. Here, as in The Spirit, Eisner butts up against the form’s restrictions; there’s too much exposition, long blocks of text that don’t quite work. A fitting conclusion to a career of more than 60 years, The Plot offers a way of thinking about comics that looks beyond the genre’s limitations even as, in its own way, it falls prey to them.

David L. Ulin is book editor of the Los Angeles Times. He is the author of The Myth of Solid Ground: Earthquakes, Prediction, and the Fault Line Between Reason and Faith, and editor of Another City: Writing from Los Angeles and Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology.