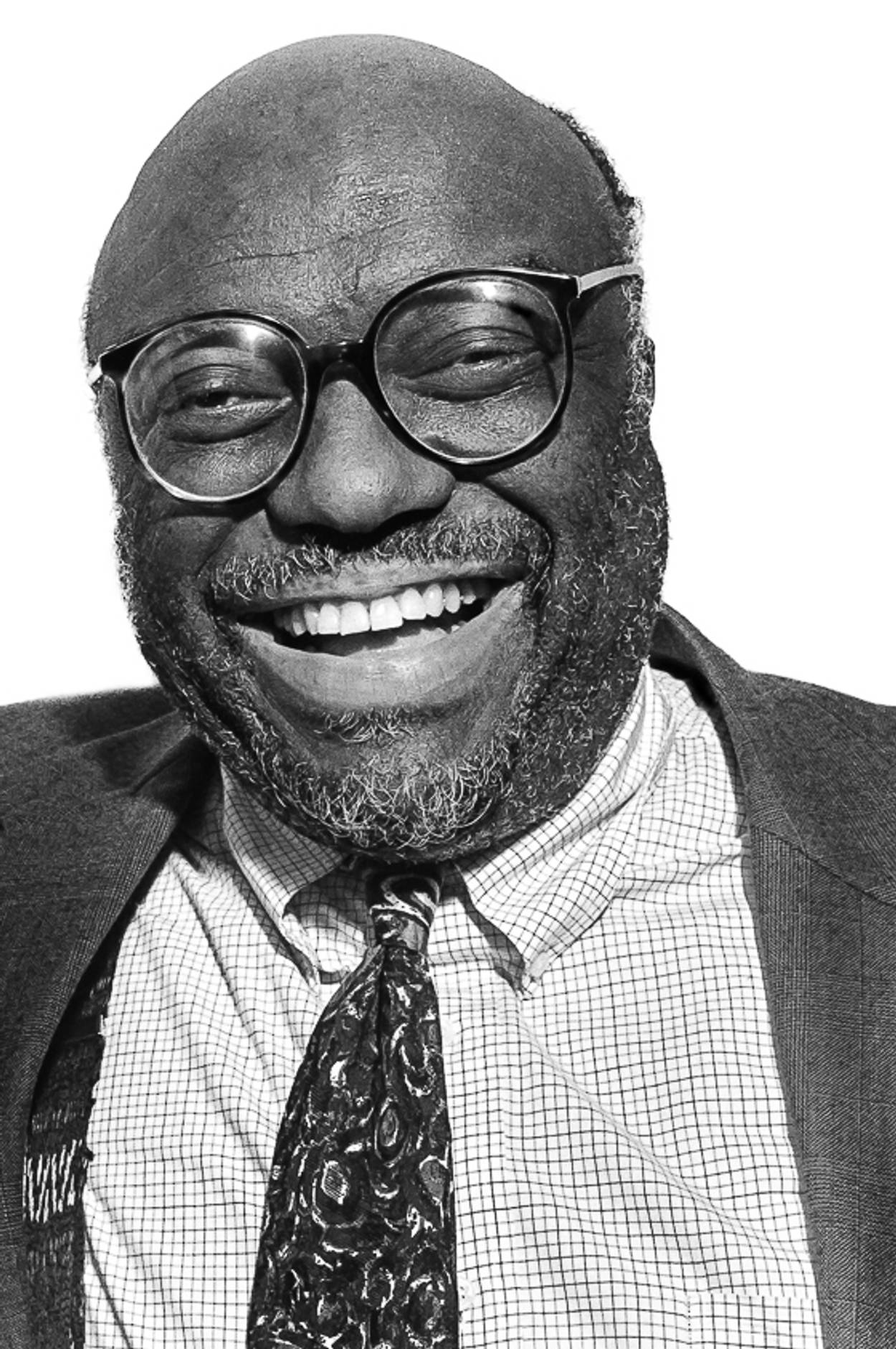

Stanley Crouch (1945–2020)

The great jazz and cultural critic, soloing over changes, sang his enthusiasm for America

In 1993, at one of the periodic highpoints of Black-Jewish acrimony, Delacorte Press commissioned me to put together a reader on Black-and-Jewish themes, and I right away went to Stanley Crouch to ask him to contribute an essay. He gave it some thought and concluded that, between his journalism and his book projects and everything else he had going, he was too busy to take it on.

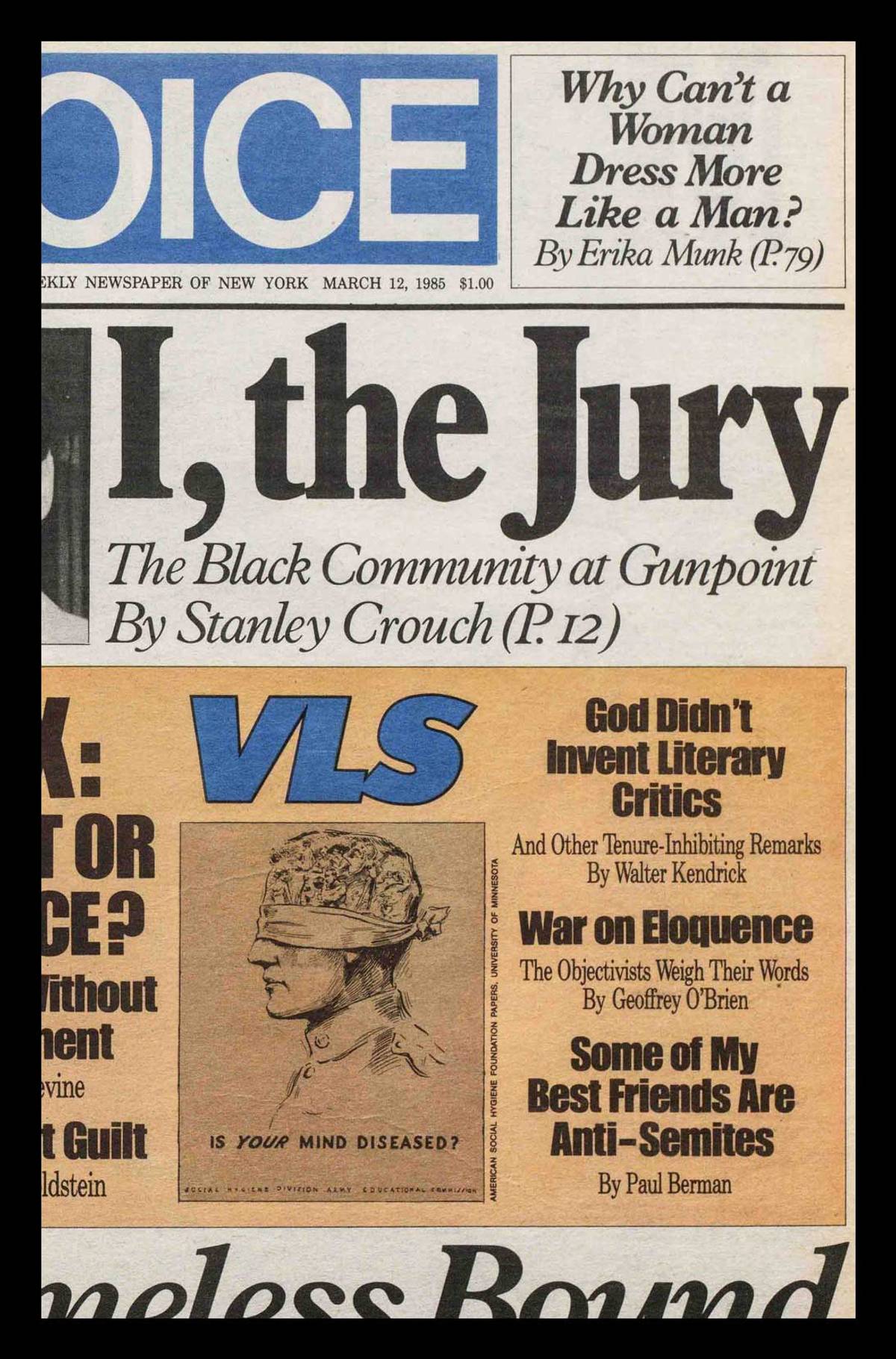

But meanwhile he and I fell into a rambling conversation, which was an old habit of ours from many years of laboring shoulder to shoulder at the Village Voice. And, as had happened many times, the talk wandered from present-day circumstances into the past and thence to our literary and intellectual heroes among the older writers. We got onto Ralph Ellison, about whom Stanley spoke often, always with reverence, and Irving Howe, who figured among my own heroes.

Stanley drew a significant portion of his own concept of how to be Black in America from Ralph Ellison, and how to be a writer and thinker (and the rest of his concept from Ellison’s comrade-in-arms, Albert Murray). And I drew a number of parallel inspirations from Irving Howe. Stanley, though, was less than keen on Howe. He tolerated Howe sufficiently to have contributed an essay to Howe’s magazine, Dissent, back in 1987, on Malcolm X. The opening sentence was aggressively blunt and vivid, in a fine display of the Stanley Crouch panache: “When compared to men like Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, Malcolm X seems no more than a thorned bud standing in the shadow of sequoias.” But it may be that, in Stanley’s eyes, Irving Howe was likewise a thorned bud.

That was because, back in 1963, Howe and Ellison had conducted a magazine debate, and, after 30 years, some of the digs and counterdigs in that debate had not entirely faded away. It was a debate about the place of politics in literature in general, and about its place in the literature of Black America in particular. Howe took the view that politics are appropriate in the novel, and angry protests against oppression are unavoidable for the Black writers of America. He granted that politics is coarsening, which makes for a tension between art and social protest.

He admired Richard Wright and the volcanic tremors of social bitterness in Native Son and Black Boy. He held James Baldwin in awe—“one of the two or three greatest essayists this country has ever produced”—but he expressed reservations about some of the early essays, in which Baldwin criticized Wright. He admired Ralph Ellison. But he considered that Ellison’s Invisible Man lacked the sharp edge of Wright’s anger. And he shook his head in disapproval at Ellison’s enthusiasm for the wider American culture—the American enthusiasm that Ellison and Saul Bellow, the author of The Adventures of Augie March, seemed to share.

And Ellison responded in a fury. Ellison considered that Howe understood nothing of the Black writer’s situation in America. Ellison explained that, if he had an oppressor, it was Irving Howe, who was telling him what to do—Irving Howe, who wanted to consign Black writers to the crudest of themes, in conformity to his own left-wing ideological predisposition. Ellison wrote: “My reply to your essay is in itself a small though necessary action in the Negro struggle for freedom.” And why did Howe speak in the voice of a guilt-stricken white, anyway, as if he were the descendant of slave owners, when Howe was, after all, Jewish—and the Jews “have enough troubles of their own,” as is well known to the Negroes? The authentic self was Ellison’s principle.

The whole thing took a personal turn, such that, by the end, Ellison introduced his concluding remarks by writing, “Dear Irving.” And both writers displayed satisfaction with what they had written. Howe reprinted his opening essay, “Black Boys and Native Sons,” in his essay collection, A World More Attractive, with its title drawn from Trotsky. And Ellison reprinted his reply, “The World and the Jug,” in his own collection, Shadow and Act—which lifted the debate upward from the lower plains of throwaway magazines to the loftier zones of bookshelf immortality.

Stanley Crouch, 30 years later, stood with Ellison, not just as a matter of personal loyalty. Ellison’s responses to Howe amounted to a personal manifesto, and the manifesto had endless meanings for Stanley himself. My own view was mixed. I recognized the legitimacy and power of Ellison’s argument, which is to say that, if I looked closely at the debate, Howe seemed to me to have been unjust to Ellison. Then again, I considered that Ellison had turned Howe’s argument into a cartoon, which was likewise unjust—an observation made very astutely by the critic Darryl Lorenzo Wellington in Dissent some years ago. Really the whole debate was an American reprise of the Russian literary quarrels of the 19th century, with Howe in the role of Chernyshevsky and Ellison in the role of Dostoevsky—a debate that Dostoevsky is deemed to have won, from a classic literary standpoint. But was Chernyshevsky wrong to insist on speaking about social conditions?

So Stanley and I were not of the same mind. Still, our conversation led to an inspiration for my Blacks-and-Jews anthology. Cynthia Ozick had written an essay on the friction between Blacks and Jews in which she took a close look at the Ellison-Howe quarrel. She came down on Ellison’s side. Ellison’s knife jab at Howe for failing to take into consideration his own Jewishness was particularly to her taste. I wrote to her and asked if I could reprint her essay in the anthology. We got on the phone. I invited her to write a postscript, too, if she had anything further to say. She was voluble, she did have more to say, and she agreed to do it.

And I went back to Stanley with an alternative idea. He wasn’t going to come up with an essay of his own. But how about if he approached Ellison and offered to conduct a dialogue, the two of them, to be taped and transcribed and edited, on the topic of the long-ago debate with Irving Howe, now that 30 years had passed? And I would go to Howe and do the same: conduct a conversation about the long-ago debate with Ralph Ellison. There was a generational logic to this idea. Howe and Ellison were men of the 1930s and ’40s, who had reacted to the craziness of those years in their respective ways. The year of their debate, 1963, may have been the last moment when the ’30s and ’40s seemed still alive. Then came the high tide of the civil rights revolution and its triumphs and everything that followed.

And Stanley and I were products of the aftermath. When Stanley was a student in California in the later 1960s, he had been a Black nationalist of some kind and a champion of the Black Arts movement. He had been a poetry-writing disciple of Amiri Baraka’s. And then, at the age of 25 or so, he had rebelled against his student rebellion, in favor of principles like Ellison’s and Albert Murray’s, which launched him into his adult career.

My evolution was vaguely parallel, given some obvious differences, and some less-than-obvious ones. I had been a militant of the New Left in college, and had subsequently entertained a few retrospective reservations, which conformed more or less to the liberal leftism that was Howe’s, with its Jewish inflection, too. (Stanley asked me: Why had I never joined the Weather Underground? I said: cowardice. He wanted a serious answer. I should have annoyed him further by asking: Why hadn’t he gone traipsing after Baraka into Maoism and conspiracy theories?—which he had never done.) And with those parallels in mind, I figured that Ellison and Howe, by speaking with, respectively, Stanley and me, would speak, in effect, to each other. Stanley and I would do the same, in effect. And, with Ozick conducting a conversation with herself on the identical theme, a mighty clamor would rise from the pages of my anthology. It would be the Jews and the Blacks of New York (some of them, anyway) at intelligent loggerheads: a Subway Series, maximally articulate, spread across the decades.

Ellison was not doing very well in those days—he would die a year later—and Stanley was skeptical that my proposal would appeal to him. Even so, Stanley himself saw a virtue in the idea. He promised to go to Ellison and make the invitation, just in case. And I went to Irving. Irving was struck by the idea. He asked for a little while to think it over. Finally he agreed. But he needed to work out his thoughts, and, for this purpose, he invited me to his apartment. He wanted to bat around a few ideas, with no tape recorder, as preparation for a later, formal conversation, to be properly taped. Irving lived in a swell apartment near the Metropolitan Museum, which he had been able to buy, I imagine, because of the success of World of Our Fathers. We sat at the dining room table, and he mused over the old debate.

He had come to the conclusion, he told me, that Ralph Ellison was right. This was not because of Ellison’s remarks on Irving himself and his Jewishness, about which he said nothing. It was because Ellison had known something that Irving had failed to see. Ellison had known that, if the Black literary world took up the kind of militant political writing that Irving thought appropriate, the results would be—well, what they turned out to be in the later ’60s and ’70s and after, in his estimation. It would not be a wave of Richard Wrights and acute social critics. It would be a wave of Amiri Barakas and gasbag demagogues—though Irving did not cite anyone by name. And Ellison had wanted to forestall the disaster.

I was surprised. I admired the ruefulness. It was big of him not to bear a grudge over certain of Ellison’s wisecracks (“Howe, appearing suddenly in blackface. ...”), which had brought any number of unfair attacks down on Irving’s head in later years. And yet, as I walked home, it occurred to me that, even so, he was still not really responding to Ellison’s objection. Ellison’s argument was not, after all, a matter of canny cultural prognostication. It was a matter of fidelity to his own artistic genius. I intended to push Irving on this when he and I got back together in two or three weeks, with the tape recorder. Only, the second conversation never took place. Irving was having health difficulties of his own. He had already had a heart attack, and now he was overtaken by another, and he did not survive. The next time I was in his apartment was for the shiva.

Meanwhile, Stanley did as promised and sounded Ellison out. Ellison declined to say anything more on this particular matter. As a result, my anthology, Blacks and Jews: Alliances and Arguments, came out the next year with Cynthia Ozick’s essay and her postscript, but without anything else on the Howe-Ellison debate, and without a contribution by Stanley (though his name came up in Ozick’s postscript). The anthology contained only one example of the multigenerational Black-Jewish conversation that I had wanted to stir up.

I asked Norman Podhoretz for permission to reprint a famous old essay of his, “My Negro Problem—and Ours,” from that same 1963, which recounts how, when he was growing up in working-class Brooklyn, Jewish boys like him were beaten up by Blacks. And I invited Podhoretz to write the kind of postscript that Ozick was writing, to bring his reflections up to date. We got on the phone. Podhoretz reminisced nostalgically about Jimmy Baldwin, from their days together at Commentary, I suppose. And he agreed to write a postscript.

But I also invited a very young and talented writer from the Village Voice, Joe Wood, to contribute his own essay. Young Wood was one of the Black writers whom Stanley, always interested in new talent, had helped usher into the Voice. He was a sensitive essayist with an easy way of speaking in the first person and a frank approach to problems of the American racial situation—an essayist in Baldwin’s style, perhaps. He took his own talent seriously, and in those days was trying to imagine his own proper place in the intellectual tradition of New York.

This became a consistent topic of conversation between him and me at the Voice, in the early ’90s. His thoughts on the New York tradition led to thoughts for my book. He reflected on a memoir from 1951 by Alfred Kazin, A Walker in the City, which conjures what it was like to grow up poor and outer-borough-ish in the Jewish districts of Brownsville, Brooklyn, during the 1920s and ’30s. But Brownsville was no longer Jewish. Jews had moved out, Blacks had moved in, and poverty had remained. Wood proposed to invite Kazin to return to the old neighborhood and stroll together through the streets, the two of them, Black and Jewish from opposite generations, and see what came of it. Kazin didn’t go for it. Wood thought he was frightened. I thought he was busy.

So Wood came up with another idea. He proposed to write about Podhoretz’s “My Negro Problem—and Ours.” Podhoretz’s theme was growing up in Brooklyn in the 1940s under attack from Blacks, and Wood’s theme was growing up in the Bronx in the 1980s, feeling under attack from Norman Podhoretz. The title of his own essay was “The Problem Negro and Other Tales.” It was the best thing he ever wrote, I think (and its best version can be found only in my Blacks and Jews reader, and not in the New York Times Magazine adaptation). But it was his best work only because a dark fate intervened. Joe went for a hike on Mount Rainier and never returned, with no sign of what happened to him—a victim presumably of a terrible hiking mishap, though no one really knows.

Ralph Ellison’s response to Irving Howe gets at the central drama of Stanley Crouch’s career. Stanley acquired a reputation—it has appeared in the obituaries—for being “controversial” or “argumentative,” a “contrarian,” which is to say, a specialist in saying the opposite of what everyone else is saying. And, to be sure, he cultivated a truculent posture, aggressive even in his vocabulary, e.g., his preference sometimes for needling everybody by using the antique-sounding name “Negro,” in favor of “Black” or “Afro-American” or “African American” (though he ended up using all of those terms).

And yet, I have never thought it right to label him a controversialist or a contrarian. The authentic literary controversialists and contrarians are writers who look upon combat as the white page that needs to be filled—writers who entertain their readers by knocking out their opponents, or go on punching because they are militants of one cause or another. But Stanley’s vanity was about poetry, and not prize-fighting, even if people say otherwise. Nor was he an ideologue. He was, instead, an intellectual, in some old-fashioned sense that hardly anyone remembers today. An intellectual is someone who understands systematic ideologies, but does not have one.

What made Stanley a controversialist or contrarian in the eyes of the world was precisely his refusal to march in the ideological parades. Everybody insisted on telling him what to do, and they did it aggressively. So the blows fell upon him, and he gave as good as he got, and he did it in a blustery newspaper style. And because he seemed to be alone in fending off his enemies, he was awarded the various belittling titles of contrarian and so forth, which shows that you can’t win.

The idea that actually governed his writing was not really a doctrine. It was an enthusiasm. Sometimes his enthusiasm was for America, the rough-and-ready civilization—the enthusiasm that was Bellow’s but more particularly was Ellison’s and Murray’s: the enthusiasm for democratic adventures and for the artistic democracy whose supreme achievement is jazz. Stanley’s American enthusiasm was regarded by the ideologues of the left and right as one more sign of his conservatism. But that was their own mistake. Then again, his enthusiasm was for the liveliness of art and the intellect. Or then again, his enthusiasm was an appreciation for aspects of the world that he had known in the Los Angeles of his childhood, back in the 1950s.

Stanley Crouch’s American enthusiasm was regarded by the ideologues on every side as one more sign of his conservatism, but that was their own mistake.

Lynda Richardson, in a profile of him in The New York Times in 1993, quoted him recalling his elementary-school teachers: “These people were on a mission. They had a perfect philosophy: You will learn this. If you came in there and said, ‘I’m from a dysfunctional family and a single-parent household,’ they would say, ‘Boy, I’m going to ask you again, What is 8 times 8?’” As it happened, he himself came from a less than functional family. His father was in jail. It was the teachers who mattered, though. “When I was coming up, there were no excuses except your house burned down and there was a murder in the family. Eight times eight was going to be 64 whether your family was dysfunctional or not. It’s something you needed to know!”

But the anecdote was more than a childhood nostalgia. The masterwork that Stanley eventually wrote, Kansas City Lightning, is a life of Charlie Parker as a boy and very young man, and some of the most interesting pages describe the Kansas City Black community of Parker’s schooldays. This was in the 1930s, which, in Kansas City and everywhere else, was a barbarous era of white cruelty and Black powerlessness. But Stanley was at pains to recount how superb, even so, was the cultural atmosphere in the Black community, and how superb was the education—how confident and serious were the teachers at Lincoln High School, who exposed their students to the best and most contemporary of poetry, which meant Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance.

The music teachers at Lincoln High were more than superb. One of them was a military band conductor who had composed the Tuskegee Institute song. The military band conductor’s student at Lincoln High was Walter Page, the bass player who went on to innovate the particular rhythmic pulse that Count Basie and his orchestra brought to the world. The conductor retired from teaching and was succeeded by another experienced Black musician, whose own student was Charlie Parker. That was some high school! The kids were fanatics of hard work.

Young Parker enjoyed the freedom, thanks to the school and its music program, to experiment playing baritone horn, trumpet, cornet, sousaphone, string bass, and piano, until he settled, at last, on the alto saxophone. His mother bought him a beaten-up secondhand one. To practice was his delight. The neighbors did not share in the pleasure. Crouch’s book quotes Parker in a radio discussion: “The neighbors threatened to ask my mother to move once when I was living out west. They said I was driving them crazy with the horn. I used to put in at least eleven to fifteen hours a day. I did that over a period of three to four years”—which suggests that, in Kansas City, even the tormented neighbors were willing to put up with quite a lot, in the interest of educating the young.

Those pages of Kansas City Lightning seem to me an extension of Stanley’s anecdote about his own teachers and the multiplication table. The pages amount to a portrait of cultural ambition in the Black community—a portrait of civilization, capable of generating the highest of high arts, even under oppressed conditions, socially, politically, and economically: a disciplined culture, devoted to the loftiest of the lofty. Kansas City in the early 20th century: a center of world civilization.

It took Stanley a while to clarify his enthusiasms, given that, during his own student years, the political and cultural fashions wanted nothing to do with memories of the 1930s and ’40s and visions of American grandeur. Still, once he had left California behind for New York and Ellison and Murray, the clarifications seem to have come to him easily. He took to flying the word “Negro” as a banner because the archaic word signified an affinity to the cultural world pre-1965 or thereabouts, before the radical breezes had begun to blow. The pre-1965 Civil Rights Movement seemed to him, in retrospect, a movement dedicated to the wholly admirable cause of “universal humanism.” And the several radicalisms that came into fashion afterward seemed to him a reactionary retreat into prejudice and even racism and, in any case, a retreat from the old intellectual and cultural standards that he had glimpsed as a child and that had proved to be, in the universe of music, a world-changing force.

Naturally his evolution away from the fads and fashions of the later ’60s left him at odds with what appeared to be the spirit of the age. His unpopularity among the Black political radicals, in particular—Baraka tore into him in verse—attracted the admiration of political conservatives, who assumed that Stanley, the reputed “contrarian,” must surely have been one of them, in his idiosyncratic fashion. But that was not true. In private conversation he could be all over the map, politically speaking, but only because he took pleasure in indulging the playfulness of his own intellect, and he was willing to give pretty much any idea, no matter how outrageous, an amused consideration. I would quote some of those forays into the forbidden and the ridiculous, spoken over lunch at the long-gone Bradley’s on University Place, except that out-of-context absurdities and thought experiments are deemed nowadays to be a criminal offense, and Stanley’s books would be piously removed from the bookstores.

In truth, he never wavered in his reverence for Martin Luther King, the universal humanist. He enjoyed quoting a clever remark of Wynton Marsalis’ about how the mythic and fiery Malcolm of Spike Lee’s cinematic imagination merely follows the example that King had already set. And Stanley was a pragmatist. Affirmative action was for many years the defining issue in regard to the political left and right in America, and Stanley was happy to declare his support for it, though without identifying himself with the left. He looked upon affirmative action as a matter of desirable “social engineering,” in his phrase, without philosophical implications.

I suppose that, musically speaking, he could, in fact, be regarded as conservative, though not because anything programmatic or ideological entered into his judgments.

His greatest hero of all was Duke Ellington, not just as musician but as a champion of Black dignity in America. But his musical appreciation for Ellington was a matter of taste, and not of doctrine. His rejection of the Miles Davis of the “fusion” era—he composed a murderous judgment for The New Republic—followed from the same musical taste. But sometimes his expressions of taste left an impression of being oversystematic. An element of surprise was missing from his criticism. Still, no one who hung out in jazz clubs with him or attended concerts at his side would ever suppose that he was incapable of spontaneous reaction. He took me to see Lee Breuer’s Gospel at Colonus at BAM in 1983, and the timbre and tones of some of the choral voices—the sexiness of the female melismas—made him spasmatic with electricity, as if short-circuiting, there in his box seat, or wherever we were sitting.

One bias that he more or less openly affirmed was for Black musicians in jazz, which was an attitude that might have struck the authentic conservatives, or at least the white conservatives, as odd or upsetting. This was partly a matter of personal affection, I think. It took a schoolteacherly turn, as if he himself were one more music instructor at the Kansas City high school, presiding over a flock of up-and-coming geniuses. I had the impression that he was always promoting one or another young Black musician, whom perhaps he had discovered. He attended a conference that I had helped organize, where a band performed, and, upon seeing who the saxophonist was, couldn’t stop himself from launching into lengthy disquisitions on the young man’s talent and prospects, to which he had evidently given serious thought.

His most famous disciple was, of course, Marsalis, with whom he struck up a relation when Marsalis was still in school. I suppose that Marsalis was, for him, the embodiment of the ideal in jazz—respectful of the history, technically masterful, opulently on pitch, elegant, robust, at home in the blues and yet not at all removed from the classical roots that likewise figure in jazz: a thoughtful musician, averse to crashing the car.

But Stanley’s bias in favor of Black musicians was mostly an aesthetic judgment. He never disputed that white musicians had contributed significantly to the development of jazz—Jimmy Dorsey, for instance, a virtuoso of the sax in the 1930s, whose technique the Black saxophonists studied. And yet, he regarded jazz as ultimately inseparable from the larger Black culture. It was the larger thing he loved, and not just the particular expression of it that bears on jazz—the larger thing that draws on African cultural memories, not only in regard to musical rhythms. The larger thing, in his eyes, was summed up in African American speech. His appreciation of jazz was, after all, a poet’s appreciation, strong on the musical qualities that can be likened to poetic prosody.

Certainly he believed that, at least in his own case, the playing of jazz and the writing of jazz criticism should have in common a lyricism in the African American vein, marked by identifiable colors and complex rhythmic swells. Music and writing were a single thing, in that respect. This was a Village Voice idea. Political writers at the Voice wanted to sound sober, but rock critics wanted to sound stoned. Or it was an idea that went back to the Beats—the idea of “bop prosody,” which was Allen Ginsberg’s phrase for Jack Kerouac: Charlie Parker’s influence on American literature. Stanley Crouch was a blues prosodist. Maybe his break with Amiri Baraka, the ex-Beat, was never as total as both of them imagined.

His writing was governed, in any case, by an exploration of tones and turns of phrase and prose rhythms in a distinctly African American vein, or perhaps several such veins. He was a master of throwing in the extra phrase. The drawl was his trope. The result was poetry, though it had to do the work of prose. And, as with many poets who write prose, essays by Stanley Crouch were sometimes a little too thick with sounds and drawled images and exotic metaphors. I think that, when he sat down to write, the demands of prose-poetry occupied three-quarters of his attention, and the demands of “telling a story,” as the jazz musicians say, occupied only what was left; and the narrative momentum sometimes lagged behind.

At the Village Voice, his editors were Robert Christgau (for his music pieces) and Ellen Willis (for some of his other pieces), rock critics both, who understood what he was about and knew how to give his copy a sympathetic consideration, never forcing their own ideas on him, but pushing him to clarify and accelerate his drafts. But too much ambition went into some of those pieces. The demands that he put on himself were sometimes more than he could meet.

He struggled with particular difficulty at other publications, where the editors were less likely to sympathize with his artistic goals. The essay on Malcolm X that he wrote for Dissent ran into a resistance from the editors there (or so I heard), whose pressure on him led to results in print that were doubtless easier to read, therefore more Dissent-like, than his original draft, but were probably less wildly colorful than whatever he had turned in—one more reason, possibly, for his demurrals on Irving Howe.

He struggled in other ways. His unpopularity in certain circles in the 1980s, his undeserved reputation as a reactionary, the anger he had to face from some of his Black readers and colleagues, above all—this was certainly difficult for him. His denunciations of Malcolm or Farrakhan in those years led, as he told me, to death threats, which must have been frightening in itself, but must also have been depressing, considering that whoever was sending those threats was probably the very reader he most wanted to address. The white radicals who disdained him as a conservative, the conservatives who admired him as a conservative, the flat-headed readers who failed to see that a Stanley Crouch newspaper column was sometimes a growly trombone solo, to be appreciated as such—everyone must have gotten him down at moments, not that he let it show. At least the Voice editors stood by him, which was wonderful.

Or did he have other troubles, not related to his writing? In the later ’80s, he seemed to me to be going through a bad period, too often on the cusp of anger, though I have no idea why. He enraged one of the women editors at the Voice by giving her hugs that were ostensibly friendly, but were, in fact, visibly angry, therefore frightening. He was the same with me at the Voice, and I am sure with many other people. Repeatedly he threw an affectionate arm around my neck and gave me a disagreeable squeeze or choke that was mildly alarming. Oh, no, I would say to myself: Here comes Stanley Crouch. And I was someone he liked. Laurie Stone, the feminist critic, was someone else he liked, and she must surely have come away with observations about this sort of thing. He roughed up the very gentle editor of the letters column, who, having published a letter that enraged him, was someone he did not like. He was the fifth-grade bully. Eventually he lost control.

One of the young Black writers at the Voice in the late ’80s, whose name I am glad to have forgotten, established himself as the single most annoying person in the newsroom—a nerdy character who looked like an accounting intern but was, in reality, the paladin of hip-hop, known around the office for medieval mentalities. I watched a quietly controlled but furious Nat Hentoff explain to the young paladin that Jewish doctors in Chicago were not, in fact, infecting Black babies with AIDS, which the young man absorbed with the sullen grimace of a student being berated by a detested teacher.

One afternoon I found a seat at one of the free desks to toil over a printout, only to discover that sitting at the next desk was the young man, staring straight ahead and listening to the boxy earphones clapped on his head. And from the tiny speakers poured a skinny torrent of herky-jerk resentfulness, together with the screaming hysteria of somebody or other, whom I imagined to be Louis Farrakhan, ranting in German. I wondered if the young man turned up the racket especially for me. Possibly he was in a trance, unaware of me. I did my best to be equally unaware of him, but the Nuremburg Rally was a lot to block out.

Stanley’s spirit of tolerance was more limited. The newsroom was open at night for deadline-chasing writers to come in and use a computer—there were never enough of them—or to work the Xerox machines. On one evening, with the office almost empty, I presided over the Xerox, and Stanley glided silently about, and somewhere else was the annoying guy. There was a commotion, and I became aware that, out of my sight, Stanley had clobbered the guy. No one deserves to be clobbered. Still, if an exception had to be made, that is the guy I would have recommended. I thought nothing of it. But it turned out that, of course, the hip-hop hero went to the higher-ups with a reasonable complaint about getting violently assaulted in their own newsroom. And Stanley was fired.

It was criminal to fire Stanley Crouch. His was the most ebullient voice in the whole of New York journalism. He was a living temple to freedom of thought. He was the bravest cultural writer in America. His writings had done nothing but bring glory to the Village Voice. He had screwed up in his office behavior, but in no other way. Why not ban him from the office, and leave it at that? He could have dropped off his prose-poetry with a receptionist, or he could have sent it by mail, and done his editings with Bob or Ellen over the phone. Why not fire the other guy? But the higher-ups had taken offense, and Stanley was gone. In this way, the Farrakhan types, who had failed to intimidate him with their death threats, enjoyed a success, after all, and his career was badly damaged.

He moved along to the Daily News and other publications, and I suppose he was all right. He wrote a few essays for The New Republic in the Leon Wieseltier era, during the years when Albert Murray was likewise writing for that magazine. But, although he went back to contributing to the Voice after a while, he never again had a home for his writings as comfortable as the one he used to have. He won a major fellowship, and Wynton Marsalis held a party in his honor, which was a touching event—Stanley looking quietly pleased, and Marsalis ablaze with pride for his beloved teacher.

Fame was his. The Daily News gave him an authentic following in working-class Black New York, as the Voice could never have done. He was on TV. People saluted him on the sidewalk. His view of clothing was competitive, and he picked his suits to out-compete. Exquisite fabrics hung from his regal frame at parties. He was a burly Henry VIII with a bulbous bald head like Lenin’s. Tina Brown took him up. But he was all along more fragile than he seemed, and it must have been a blow to discover that, at a difficult moment, the Village Voice, which had always stood by him, did not stand by him.

I do not know when he began working on the Charlie Parker biography, but I remember that, early in the 1980s, the biography already occupied more of his conversation than anything else he was doing. He and I strolled through the Village after work, and Parker himself seemed to be strolling at our side, alive and cantankerous. And, sure enough, over there, on the other side of Ninth Street, was Parker’s daughter! His step-daughter, that is—visible, and then lost in the crowd before I could see which face Stanley was pointing at.

The decades went by, though, and I concluded, as many of his friends and editors must have done, that Stanley was made for the quick sprints and Olympic pole-vaulting of cultural journalism, and not for the long distance of books. That was another mistake, however. He talked for nearly as many years about his novel, Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome, and then, sure enough, in 2000 the novel appeared, a white whale of a thing, with its ambition advertised by a triple dedication to Albert Murray, Ralph Ellison, and Saul Bellow, “mentors all.”

Bellow blurbed it, too: “What one feels in reading Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome is an immediate relief from the burden of ideology”—though, if you give the blurb any thought, it makes the novel’s virtues sound like those of a tract. John Updike’s review in The New Yorker was murderous. Updike made the book appear to be a soup of romantic sentimentality, spiced with little essays in the Crouch style, and, then again, watered down with excesses of loquacity. Stanley insisted to me that I read the book, but each time I have opened it the narrative momentum has failed to catch me up—though I have never doubted that Updike was correct in detecting a variety of mini-essays, some of which must surely be brilliant.

By 2006, when Ellen Willis died, the slide into his own ill health had already begun, such that, at her funeral, the freaked-out look in his eyes made clear that funerals had become, for him, something more than a moment to mourn the passing of someone else. He was having tax troubles, too. I ran into him regularly during the next years, sometimes at literary events, or on the sidewalk in Brooklyn, after he had moved out of the Village. I ran into him at the Upper East Side parties of our mutual friend, Barbara Probst Solomon, where he looked prosperous, stately, jocular, quietly assessing each new guest, the “Hanging Judge” at play. But sometimes he was haggard.

The phone calls came a few times a year. These were no longer like our random Village Voice conversations in the ’80s, devoted intermittently to the physiques and braininess of our female colleagues, but were, instead, hourlong shared ruminations on politics, or music, or Jewish or Israeli themes, topics of interest to him, or on my own writings, about which he had stylistic observations to make, or on the progress of his books, or on the indignities that we put-upon writers have to endure, requiring mutual reassurances, which both of us were happy to give and receive—until the calls ceased coming. We seemed no longer to run into each other, either. And just at that moment, in 2013, the Parker biography, appeared, at last, after a gestation of some 30 years—the biography in its first volume, at least.

Now, here is something I cannot explain. To write well requires a robust physical strength, which might sound implausible but is nonetheless true. I would have imagined that Stanley’s health problems, whatever they were, might have sapped the power from his pages. But not at all. He seemed to have arrived, instead, at a degree of control of his own several gifts. He had learned the art of compression, and the discipline of controlling the garrulousness, and the art of painting on large canvases and tiny canvases at the same time, perhaps not consistently. But intensity was always his main idea, more than suave perfection.

The prologue to Kansas City Lightning is three short italicized paragraphs, and, in a feat of poetic compression, those three paragraphs contain the whole book. Or perhaps they contain the major part of Stanley’s vision, artfully reduced to the stanzas of a prose-sonnet:

In West Africa, a man dances atop stilts rising more than nine feet in the air. His bold turns, leaps, and spins suggest the power of human beings to master the subtle-to-savage disruptions of rhythm and event that define experience.

In New York, on a bandstand at the Savoy Ballroom, Harlem’s “home of happy feet,” alto saxophonist Charlie Parker plays for the Thursday night courtship ritual of the “kitchen mechanics”—the female domestics on their night off, dressed in homespun Cinderella finery. The shine of their skin, in all of its various tones, is muted by beige powder; rouge colors their lips; their hair is done up in gleaming black scrolls. They wear their dresses, solid or print, as close as sheathes; the heels on their pumps seem made of springs; they wear flowers behind ears heated by the talk of their lovers, their husbands, and the wolf packs of pimps anxious to recruit them for the bedroom mechanics of sexual theater for hire.

With the Jay McShann orchestra shouting behind him, Parker—a great ballroom dancer himself, whose high-arched feet force him to move from his heels—choreographs his improvised melodies through the saxophone. Feinting, running, pivoting, crooning, he is inspired by the dancers and inspires them in turn, instigating them to fresh steps.

The first paragraph, about the stilt-dancer in West Africa, conjures the goal of art, which is to master experience. And it attributes the particular notion of art that was Parker’s to African origins. The second paragraph, about Thursday nights at the Savoy, conjures a reality of African American life in the 1930s and ’40s, which is proletarian, desirous, happy, and beset by the degradations of poverty. Or, by implication, the second paragraph conjures the larger reality of African America in those decades—hardworking, oppressed, and yet autonomous and stylish.

The third paragraph conjures the ultimate theme of Crouch’s book, which is Parker’s art: the melodic improvisations, and the dialectic between his artful improvisations and his Black and proletarian public. Or the third paragraph conjures something larger, which is a Romantic concept of art, as if drawn from Victor Hugo and his notion of artist-prophets, or drawn from Emerson and his “Representative Men”—a concept of the artist as hero, alone on the windy heath. But there is no reason to invoke Hugo and Emerson. The third paragraph reprises Albert Murray’s entirely Romantic idea: the blues as heroism.

The book consists of detailed reports on Parker and his progress in love and life and music, alternating with portraits of the development of jazz, the new art form, alternating with portraits of the larger cultural scene in the 1930s and early ’40s, as viewed from the African American world of Kansas City and beyond. The larger scene is, of course, dismaying. The brawny, industrial America of the majority population in those years is an ugly and bigoted place, from the standpoint of the African Americans.

It is the America of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and its lasting influence on Hollywood, the America of minstrel shows and mockery of Blacks—the America that, by 1939, was still flocking to a grotesque movie like Gone With the Wind, even while buying the bestselling record of Coleman Hawkins’ pure jazz version of “Body and Soul.” This is the ambiguous and monstrous America that you see in Richard Wright’s books, except that, in Black Boy, the autobiographical hero wrestles his way to strength and achievement with the very peculiar help of the mostly white Communist Party in Chicago, even if the Communists turn out to be dangerous lunatics.

In Crouch’s book, the Black community likewise wrestles its way to strength and achievement. But it does so on the basis of its own power and creativity, with scarcely any role for whites, except as figures in a distant landscape. You see this in the history of jazz that he recounts—from New Orleans in the 1890s, to Chicago 20 years later, and thence to Kansas City in the 1920s and ’30s and to scenes that he pictures in close-up: the Reno Club and its jam sessions on Twelfth Street and Cherry, where young musicians who got up their courage could test their talent, at the risk of public derision and humiliation.

He reports white musicians dropping by at the Reno, from time to time—Benny Goodman, notably, who, in 1935, made his way to the bandstand, where he was welcome to play, and was demolished, musically speaking, by the normally reticent and scholarly alto saxophonist Buster Smith, the composer of “One O’Clock Jump.” But an occasional visit by someone like Benny Goodman did not make the Reno any less of a Black scene.

The next year was Charlie Parker’s moment, at age 16, to get up his courage. Crouch gives us young Parker’s internal experience, making his way to the Reno bandstand with the broken sax that his mother had bought for him, held together by tape:

The instrument seemed heavier, the reed almost the size of a tongue depresssor, the buttons on the keys slippery. He could feel his every breath, almost the flow of his blood, the indifferent presence of his nervous system. It was warmer on the bandstand, the lights and the shadows more intense. Everyone seemed to be staring at him, looking at no one else. What tune would they call? Would he know it? He knew he would know it. Would they give him any mercy? He didn’t need any mercy. He’d listened to them plenty. He was sweating. Everybody was relaxed except him. They were smiling. Were they laughing at him already? His stomach was fluttering. It was hot up there. What tune would they call? He knew better than to suggest something. You didn’t do that, not unless they asked. Why would they ask him? All he could do was wait, every sound in the club, every color, every smell more vivid than he had ever known. It was a long, long wait. Then they called the tune and he was in the middle of everything, the piano vamping in the song, the bass humming out the harmony, the drums setting a pulsation of metal and skin. He knew it! He knew the key, too. Charlie could hardly hold himself back. This evening he would get it right. This was it. Now was the time.

Only, disaster! Charlie did not get it right. Jo Jones, the drummer, drove him off the bandstand by ringing on his cymbal—which shows one more time that a career like Charlie Parker’s was not a miracle of nature. Charlie Parker was not, in Crouch’s words, “an innocent into whom the cosmos poured its knowledge while never bothering his consciousness with explanations,” though Parker liked to pretend that he was. Nor is jazz itself a miracle of spontaneity, not in Crouch’s presentation. Jazz is the illusion of spontaneity, which is something else entirely—an art that drapes itself like a robe over a science, requiring intensive study and a theoretical command.

But Crouch’s book consists, as well, of the rhythms and tones of his own voice on the page—the sounds of the English language, dispersed, like the voices of the individual players in the Duke Ellington orchestra, into separate and distinct sonorities. The passage I have just quoted, with Crouch conjuring young Parker’s thoughts on the bandstand, observes a simple discipline, light on the ornamentation. In other passages, though, he drawls his pace by throwing in an extra word or two and occasional riffs of folksy philosophical commentary, serving a rhythmic function.

Buster Smith learns how to please an audience as a neophyte musician in Texas:

Buster was finding out, as all bluesmen had to, that the audible route to success was through creating subtlety and fire in the tones and timbres of Negro American speech and rhythm and song. You had to be able to soothe the people or insinuate them into reverie; you had to be able to make them rise up, stomp, kick, spin, and caress; you had to remind them that the sandpaper facts of human life could be smoothed over if met in the close quarters of courtship or celebration, where the sun going down at the arrival of evening promised recognition of something far inside the soul and right under of the skin. None of the sweet, sentimental music white folks listened to was for them. They needed stuff played that was as tough as they knew the world to be, and that was as compassionate as they wished it would become. The kinds of voices they heard in their daily lives had to rise out of the horns; the intervals they liked had to be rolled or trilled or boogied out of the piano; the backbeats they liked to set their dance steps to were expected of the drummers. And, working in his little trio with pianist Voddie White and drummer Jesse Dee, Buster Smith met the demands of Dallas.

In still other passages, Crouch leaves the paraphrasing behind, and he quotes directly the language of one or another individual in Parker’s world. He was able to locate Parker’s high school girlfriend and first wife, Rebecca Ruffin, half a century after high school and some three decades after Parker’s death, in 1955. He lets her speak in her own voice, this time with a few departures from standard English, in tones that are hers, and not his. The graduation ceremonies at Lincoln High have concluded:

“After graduation, we went downstairs in the gymnasium, the junior/senior reception,” Rebecca recalled. “We ballroomed all over the floor. He could really dance. I was surprised. Charlie Parker could surprise. You couldn’t be sure what he knowed and what he didn’t know. If he was interested, he would study. If there was information, Charlie would get it. I don’t know where he learned, but there he was at the reception dancing just as good as he wanted. He danced on his heels. Oh, he was so proper. He really did grow up ... The band was playing, and we were just out there on almost every dance, turning this way and turning that.

“It was a perfect evening. We were so in love. Cupid had shot us good.”

Here, then, is a prose that, from one passage to another, shifts keys dramatically, and yet effortlessly, as if going from the bright standard tones of the key of C (in the description of young Parker on the bandstand) to a slightly warmer B flat (in the description of Buster Smith pleasing his Texas audiences) to the heartbreak key of D flat, the “Body and Soul” key, in which Cupid shoots us good. Where did Crouch learn to make those shifts in key? The skill was intuitive.

Still, it is interesting to note that, in the acknowledgements section of Kansas City Lightning, he once again cites Bellow, together with Ellison and Murray. Bellow’s place on that list might seem a little odd, given that Bellow is sometimes thought to have displayed a less than acute sensitivity to African American themes in his novels and elsewhere (even if he also wrote a brilliant review of Invisible Man in Commentary). But Crouch’s view was admiring.

I can imagine that, from Bellow, he might have derived some of his gusto for big-city portraiture, which, in Kansas City Lightning, leads him to write with a tender appreciation for the Tom Pendergast machine in Kansas City and the William Thompson machine in Chicago—the big-city machines that allowed the jazz clubs to flourish. But there is something else. Bellow was not a writer on music, but he was a master of shifting musical keys in his prose.

Bellow knew how to shift from a standard American English to a lofty English elevated by the grandeurs of world literature, to a Chicago street lingo, to the subculture of gangster language, to the shadow of another language entirely, which is a subterranean Yiddish. And he knew how to weave those several keys or dictions into a verbal richness that was not just poetically interesting but suggested the richness of society, with its levels of social class that are also levels of emotion. Crouch’s English naturally draws on a different set of subcultures and idioms. But the shifting of keys is similar. The shifting of keys is Crouch’s hidden theme, or one of them.

His main theme, however, is himself. He is a theatrical writer, and his goal as often as not is to get you to watch him perform. No one is going to suppose that, even at his finest, his individual performances, considered as contributions to American literature, reached the level of his literary heroes. Still, his ambition matched theirs. He considered himself one of the greats, even if he wasn’t, except in flashes. But he was a serious man, and there was always something thrilling in watching him make the effort. The reliable solidity of his instinct was part of it—his instinctively heroic concept of the African American story and its place in American democracy, and his concept of jazz at the center of the story. But at the deepest level his ambition was a matter of verbal tone.

He explains in Kansas City Lightning that, in the 1930s, the jazz musicians considered themselves an elite, which obviously they were. They were a group of musicians who had conceived of music in a new and brilliant and difficult way that other musicians did not understand and could not play. But they were an elite who also measured their superiority in a fiercely individualist manner. Each musician within the elite wanted to demonstrate that not only could he meet the technical demands of the most challenging jazz, which few musicians could do, but he could produce a sound on his own instrument that resembled no one else’s—a golden sound, or a smoky one, or gritty, or overintense, or laid-back, or something, which, because it was true to the individual musician, nobody else would be able to duplicate. An elite of technically superior hyper-individualists: That was the idea. That was Stanley Crouch’s idea, as well. He wanted his voice on the page to sound like no one else’s among the American writers—and, sure enough, his voice, confident and melodious, sounded like no one else’s.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.