Stop Yeshayahu Leibowitz!

By failing to name a street after the controversial philosopher, the city of Jerusalem proved he was right

There’s a street in Jerusalem named after Benjamin Netanyhau’s father and another named after David Ben Gurion. Some streets are named after famous rabbis, others after former mayors. Many have biblical names, and some are named after fruit or animals. One street is even named Stairway to Heaven, which may or may not have something to do with the Led Zeppelin song. But there’s no street in Jerusalem named after the world-famous philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz: Last week, just moments before the city council was slated to vote on whether to honor the late Jerusalemite by attaching his name to a sliver of the city in which he’d lived, the city’s mayor, Nir Barkat, withdrew the proposal, bringing the decade-long effort to commemorate Leibowitz to a fizzle.

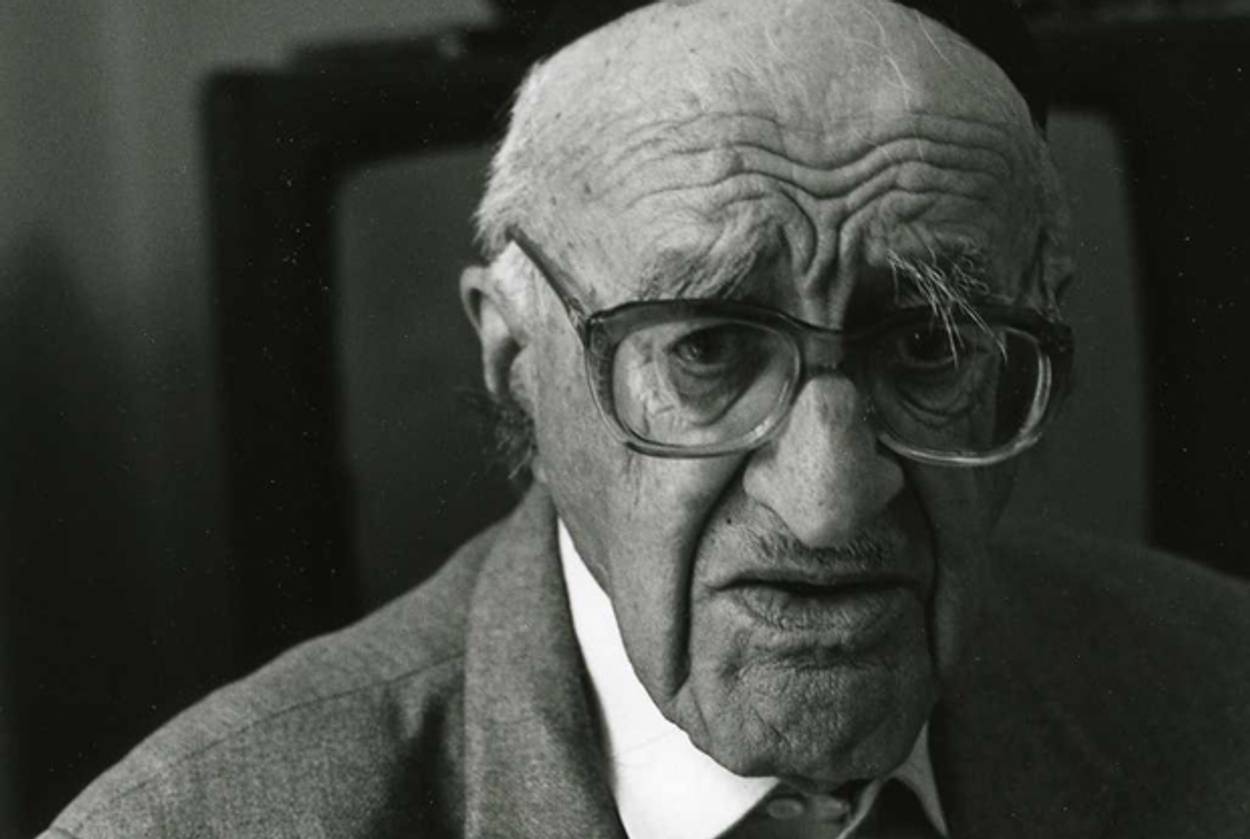

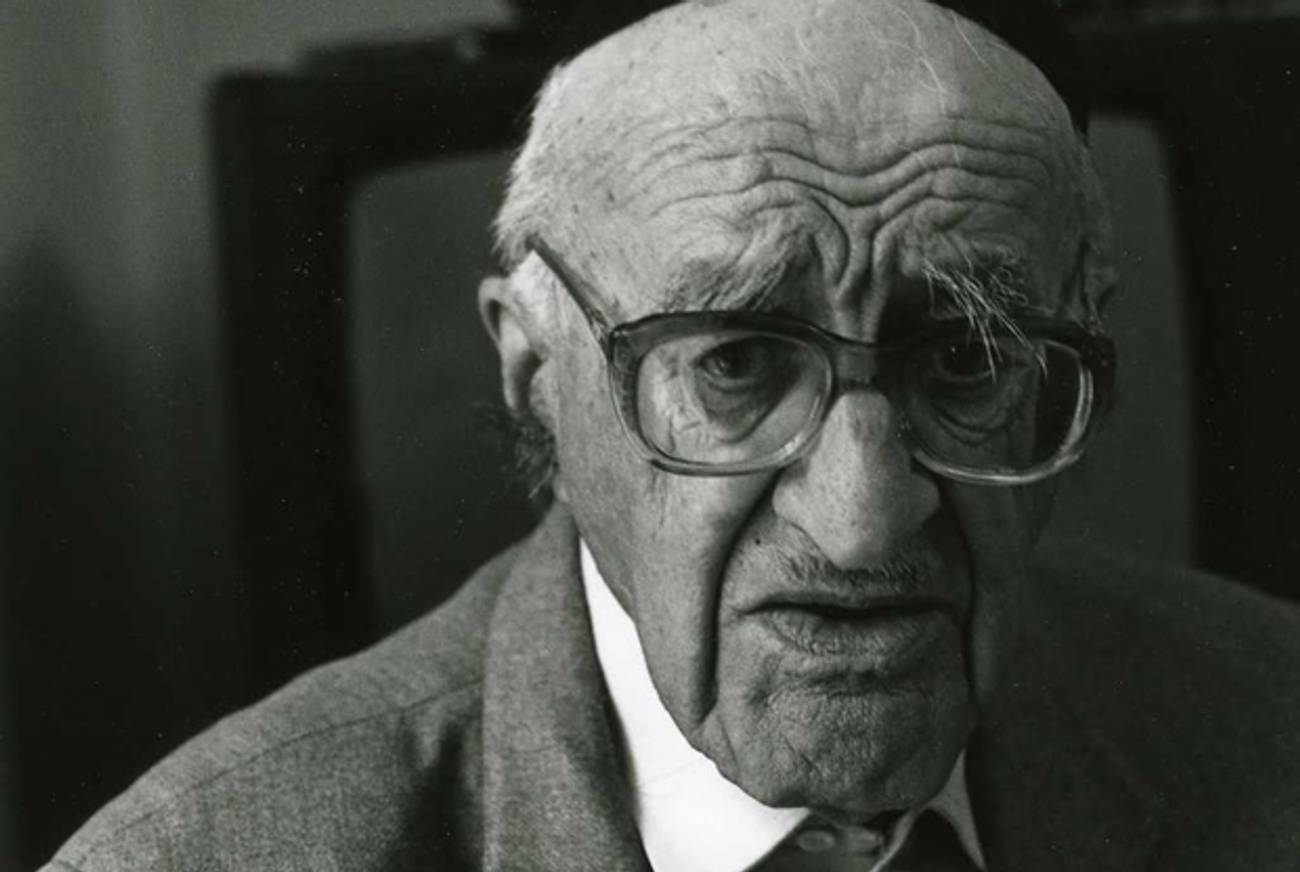

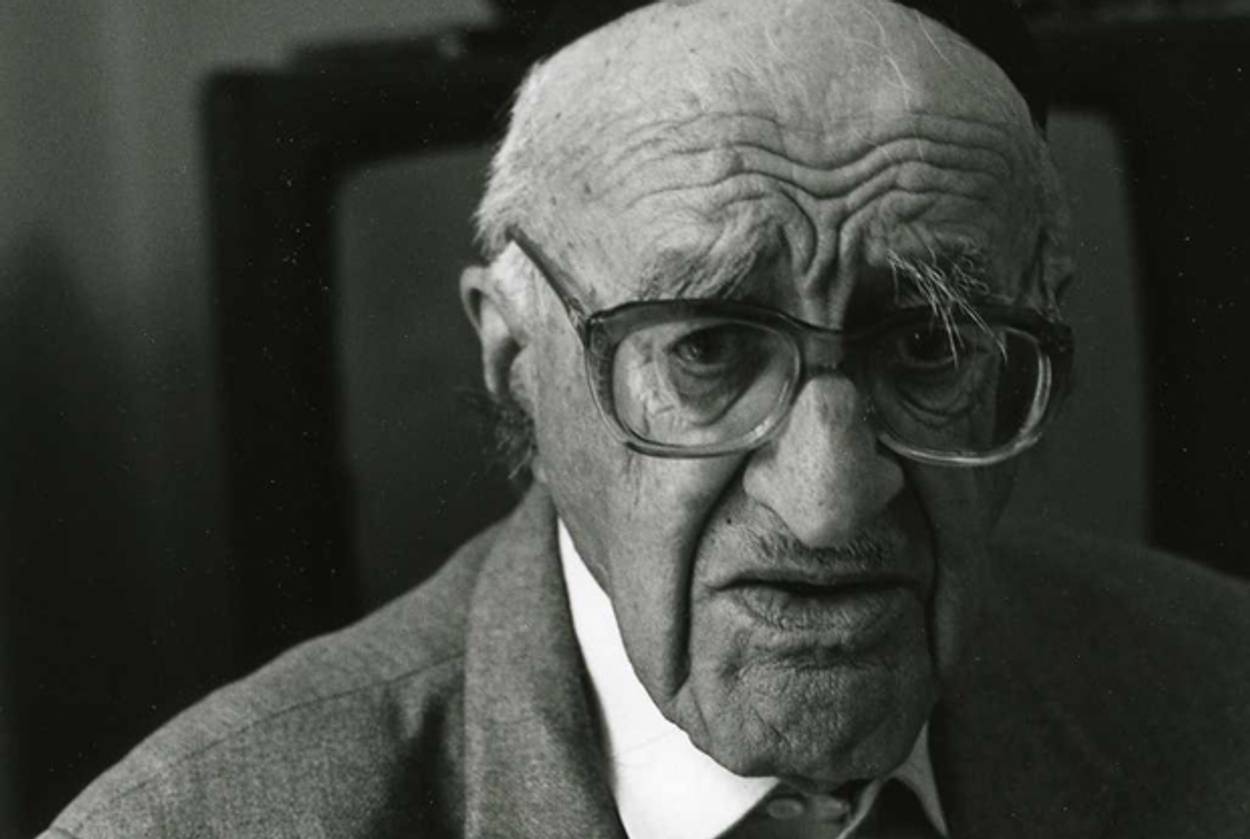

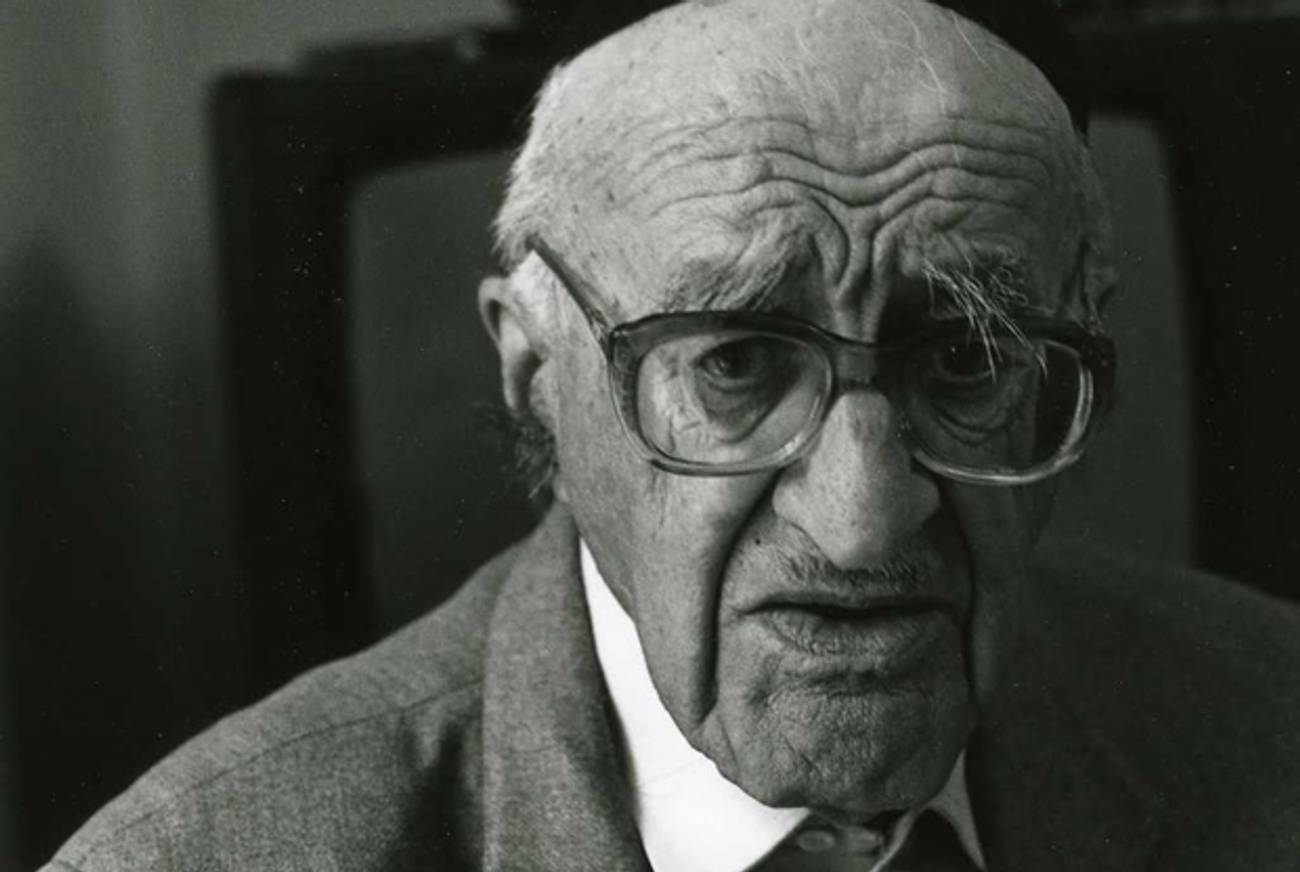

There are many reasons why one might have opposed bestowing upon Leibowitz the high honor of cartographic permanence in Jerusalem: His views on Judaism were controversial, his politics radical, and his tongue swift and sharp. In July of 1967, just a month after the Six Day War, he wrote a public letter decrying the ecstatic triumphalism most Israelis felt in light of their quick and glorious military victory. Tongue firmly in cheek, Leibowitz, then already in his late 60s, suggested that the newly liberated Western Wall be turned into a discotheque, named “The Disco of the Divine Presence.” This, he wrote, would please everyone, “the secularists because it’s a disco, and the religious because it’s named after the Divine Presence.”

The war and its aftermath gave Leibowitz new prominence. He was already known as a chemist and a supremely interesting thinker who believed, riffing on the Rambam and taking Maimonides’ thought to its logical end, that faith was irrelevant and that observing the commandments was the only thing that mattered. For these views and others, he was celebrated and accursed, but he was hardly a household name. This changed with the sudden conquest of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and the settlement project that followed. The occupation, Leibowitz warned then, would bring about a catastrophe. Once Israelis came to understand their ethnic and religious identity as inseparable from the state and its army, he argued, they had embarked on a path not dissimilar from that pursued by the Germans in the 1940s. An Israeli Auschwitz, Leibowitz said, with Palestinians recast as Jews, was “inevitable.”

It was just one of many Holocaust-inflected statements he made. Born in Riga in 1903, and having emigrated to Palestine in 1935, Leibowitz had escaped the Nazi horrors, but they nonetheless remained vivid in his mind. Criticizing Israeli judges who permitted the torturing of Arab detainees, he called them “Judeo-Nazis”; in the four decades that have passed since, the coinage lost little of its shock value.

Despite his passion for political bomb-throwing, however, Leibowitz was first and foremost a complex and original thinker. Like his cousin, Isaiah Berlin, he saw positive liberty—the power to fulfill one’s potential, as opposed to negative liberty, which was merely the absence of restraint—as central, and argued that only by observing the mitzvot could a Jew overcome his base nature and assert his true freedom. Also like Berlin, Leibowitz was a deeply humanist thinker, although he often denied it by arguing that it was only Halachah, not universal morals, that mattered to him. Few took the distinction to heart.

As the divide between Israel’s left wing and its right grew deeper, Leibowitz became a prophet of sorts for a generation of liberal Israelis who would embark on pilgrimages to the professor’s modest house in the Rehavia neighborhood of Jerusalem. He would receive them warmly, speaking more softly than he did when thundering about God and war and the settlements. He had once said that a prophet was someone who spoke not of what was going to happen, but of what ought to happen, and to many young Israelis, this was precisely what Leibowitz was doing.

Like every prophet, he approached his earthly travails with a measure of indifference. In 1993, for example, he was nominated for the Israel Prize, the nation’s top honor. Shortly after his nomination was announced, he spoke in a political gathering in Tel Aviv and argued that the Mista’arvim—an elite IDF unit that dressed up like Palestinians, infiltrated villages and towns, and conducted arrests—were Israel’s equivalent of the Hamas. The bereaved father of a Mista’arev killed in action sued Leibowitz for libel, and a call to retract the prize rapidly gained supporters on the right. Leibowitz, on his end, was unfazed. “I didn’t consider the entanglement that will follow after my nomination for the Israel Prize was announced,” he said. “Now I wish not to receive it. I already got my recognition. My honor is intact.”

It was a remarkable conclusion to a remarkable affair, one in which all sides behaved with restraint wildly uncharacteristic of Israel’s tempestuous political climate: Arguments were made, counterarguments were offered in return, and everything was calmly and politely resolved.

And, for a while, it seemed like the most recent controversy involving an attempt to honor Leibowitz by naming a street after him would follow the same pattern. Yosef “Pepe” Alalu, a city council member for the left-wing Meretz party and the driving force behind the naming initiative, got up and said that “naming a street after Yeshayahu Leibowitz doesn’t just honor the man, it honors the city.” On the other end of the political divide was Likud councilman Elisha Peleg, who argued that Leibowitz “hated the IDF and incited against it. He dismissed fundamental Jewish traditions and called for discord within the Jewish people.” The late professor, Peleg concluded, “isn’t worthy of being commemorated in Jerusalem.”

But while reading aloud a list of Leibowitz’s most incendiary comments, all of which contained at least a grain of truth and were intended to provoke arguments both philosophical and practical, Peleg included one he knew would have a profound effect on his listeners: The professor, he reminded his fellow council members, had once called Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the spiritual leader of the Shas party, a “stupid idiot.”

The nature of halachic Judaism or the occupation of the West Bank can be debated endlessly, and even calmly, by intelligent people, but a decades-old insult to Ovadia Yosef? The debate about the late great philosopher and provocateur of Jerusalem was now over. “In light of these harsh quotes” said Eli Simhayoff, the chairman of the Shas faction in the city council, “we are sweepingly voting against (the proposal) and are condemning every word he said against our master.” With Shas and the Torah Judaism, another ultra-Orthodox party, holding nearly half of the council’s seats, the proposal seemed doomed. Rather than risk a public spectacle, Mayor Barkat withdrew the proposal.

It was an ending Leibowitz himself might have enjoyed, and certainly one that wouldn’t have felt foreign to the small and slim scholar with the thick glasses. Having spent considerable time decrying any connection between religion and the state, he was now being censured by clerical servants in senior political posts. Naming a street after a philosopher is one sort of honor, but proving him right may be the highest possible tribute to his memory.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.