In Cultural Amnesia, Clive James’s eccentric encyclopedia of modern culture, the Australian critic devotes some of his most enthusiastic pages to Tony Curtis. One might not think that Curtis, whose fame rests more on his beauty and his outsize personality than on the quality of his movies, deserves to be ranked as one of the essential figures of the twentieth century, alongside Thomas Mann and Margaret Thatcher. But to James, who saw Curtis’s movies as a teenager in post-war Australia, the actor—with his frank sexiness, his adolescent intensity, his comic zest—seemed to incarnate the glamour of the American century.

The irony, of course, is that to Americans, Curtis looked like anything but an all-American boy. Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda, with their WASP uprightness, were the kind of actors chosen by Hollywood’s Jewish filmmakers to be icons of American heroism. Curtis, on the other hand, was undisguisably ethnic. There may have been Jewish movie stars before Curtis, from Emmanuel Goldenberg (Edward G. Robinson) to Issur Danielovitch (Kirk Douglas). But none of them sounded like Bernie Schwartz, who, even after he changed his name, was unmistakably a Jewish street kid from the East Side of Manhattan. It’s no coincidence that the one line of Curtis’s everybody knows is Yonda lies da castle of my fadda”; a silly phrase given an ethnic mangling, it seems to encpasulate his whole career and persona.

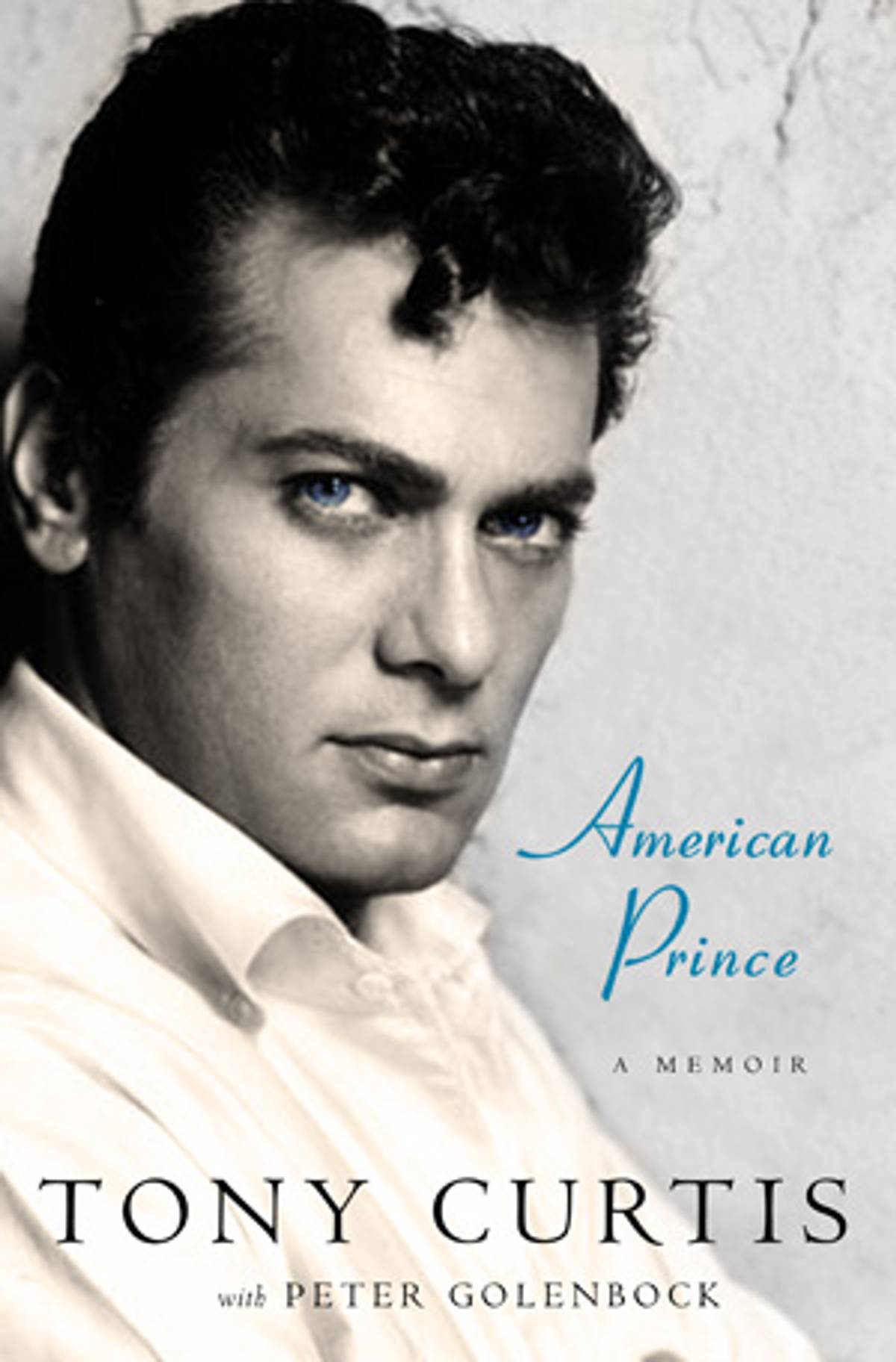

In American Prince, his utterly synthetic, deeply unreliable, yet fascinating new memoir, Curtis does not fail to defend himself against that infamous line. In the first place, Curtis insists, what he really said in Son of Ali Baba—the 1952 film he describes, with admirable directness, as a another sand-and-tits movie”—was Yonder in the valley of the sun is my father’s castle.” More important, his accent was not especially notable in the movie—no more so, at any rate, than in Some Like It Hot or The Defiant Ones or Sweet Smell of Success, to name some of his more enduring films. The line didn’t become notorious, Curtis says, until Debbie Reynolds made fun of it on a talk show: Did you see the new guy in the movies? They call him Tony Curtis, but that’s not his real name. In his new movie he’s a got a hilarious line where he says, ‘Yonder lies the castle of my fodda.’”

You could chalk her ridicule up to my New York accent,” writes Curtis (as channeled by Peter Golenbock), but when she mentioned the issue of my real name on television, I began to wonder if there was something anti-Semitic going on there.” And while immersed in American Prince, this roiling stew of Curtis’s grievances and boasts, the charge of anti-Semitism does seem plausible. Everybody changes their name in Hollywood, after all—Janet Leigh, Curtis’s first wife, was born Jeannette Morrison—so why should Bernie Schwartz’s fake name be especially noteworthy? And why should a Jewish accent be considered more inherently anachronistic than, say, the plummy English of Laurence Olivier, with whom Schwartz played a famously suggestive scene in Spartacus?

The answer, Curtis has no doubt, is that Hollywood in the 1950s was a closed caste, which had no place for a Jew—at least, for a Jew like him. Curtis, born in 1925, had grown up in one of those very poor, very troubled immigrant Jewish families whose miseries you can read about in the fiction of Delmore Schwartz and Daniel Fuchs, or the memoirs of Alfred Kazin. His mother was frustrated, vindictive, and unstable—later in life, Curtis writes, she would be diagnosed with schizophrenia—while his father, a tailor, struggled to stay afloat during the Depression. The family would sometimes have to squat in the tailor shop; on one traumatic occasion, when Curtis was 10 years old, his parents deposited him and his younger brother in an orphanage for two weeks. As a young boy, he writes, he was constantly bullied—by gentiles for being a Jew and by other Jews for being poor. The worst blow came when Curtis was 13 years old, when his younger brother, Julie, was killed by a truck at First Avenue and 78th Street. His parents sent Curtis to the hospital, alone, to identify Julie’s body.

No wonder Curtis dropped out of high school and joined the Navy when he was just sixteen years old, forging his mother’s signature on the parental consent form. And no wonder that, when he came back to New York at war’s end—never having seen combat—he immediately found another kind of escape in acting. His first professional job involved touring the Catskills in a a play about anti-Semitism and the Jewish experience in America,” whose bathetic title—This Too Shall Pass—Philip Roth would have been proud to have come up with. Curtis also worked briefly in the Yiddish theater in Chicago, where he kept himself entertained in schlocky roles by ad-libbing lines like I would rather be in the movies!”

Soon enough he was, thanks to a Universal talent scout named Bob Goldstein. And here begin the reader’s doubts about the anti-Semitism that, according to Curtis, froze him out of Hollywood’s A-List. Bob Goldstein discovered Curtis; Jack Warner befriended him on the plane to L.A. (one of the many moments where Curtis’s story conforms a little too perfectly to Hollywood archetype); Abner Biberman was his studio-assigned acting coach; Lew Wasserman and Swifty Lazar were the agents who made his career; Billy Wilder gave him his best part. All of these men, of course, were Jewish, as were the moguls who built the studio system in the first place, and many of the producers, directors, and writers who still ran that system when Curtis was signed as a contract player in 1948.

Curtis never remarks on this obvious fact, which rather undermines his insistence that being a Jew was a strike against you in Hollywood—as it was in most places.” Yet American Prince makes it possible to understand why Curtis could believe this. He was not looking at the whole ecosystem of Hollywood—he regrets, late in the book, taking so little interest in writing or directing, which might have sustained his career after he outgrew leading-man parts. He was only concerned about the intricate status hierarchy of Hollywood’s stars, and in that hierarchy, it is true, WASPs held the highest places. Curtis writes feelingly about ancient snubs from stars like Debbie Reynolds and Henry Fonda and Ray Milland: to him, a New York Jewish drop-out, such people seemed like prom kings and queens. Even late in life, when Curtis was rich and famous, he was hugely insecure about his Jewishness. He married his third wife, a model named Penny Allen, because she was the shiksa goddess of my dreams. Heaven knows, when I was a kid I couldn’t have imagined even talking to a girl who looked like Penny Allen.”

This insecurity, American Prince makes clear despite itself, helped to turn Curtis into a titanic narcissist. His need for approval is insatiable, leading him to pursue every woman he meets and accept every role he is offered, no matter how terrible the picture. His treatment of his parents, children, and especially wives is frankly appalling. Of course, it is impossible to say how much of Curtis’s unassuagable neediness can be chalked up to his Jewishness and how much to his other psychic traumas, or simply to the typical actor’s neuroses.

Yet Curtis doesn’t fully appreciate how much his on-screen allure owed to his being Jewish. Like Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, and James Dean, who arrived in Hollywood at the same time he did, Curtis was a new kind of Hollywood leading man, whose appeal flowed from his neurotic intensity and exotic, almost feminine beauty—a whole different type from the Jimmy Stewarts and Cary Grants of the past. And it was Curtis’s Jewishness—including the wounds that resulted from it—that allowed him to fit this new image of American masculinity so perfectly. To the teenaged Clive James, watching Son of Ali Baba in Sydney, even Yonda lies da castle of my fadda” sounded quintessentially American: Nothing mattered except the enchanting way that the tormented phonemes seemed to give an extra zing to the American demotic.”

Adam Kirsch is the author of Benjamin Disraeli, a new biography in Nextbook’s Jewish Encounters series.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.