Stranger Than Pulp Fiction

Crime writer Ed Lacy died 45 years ago. Few knew he was also a New Yorker contributor and communist darling.

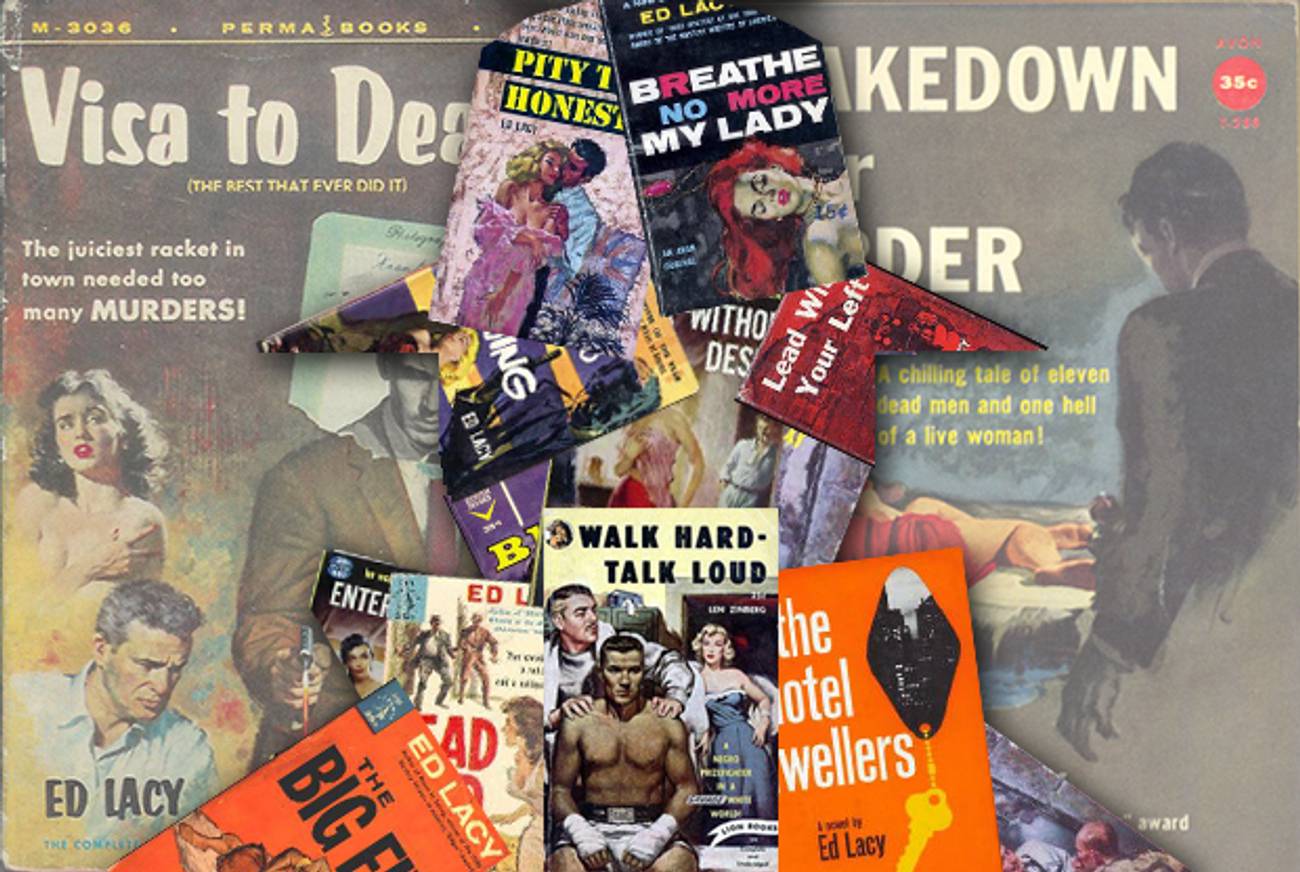

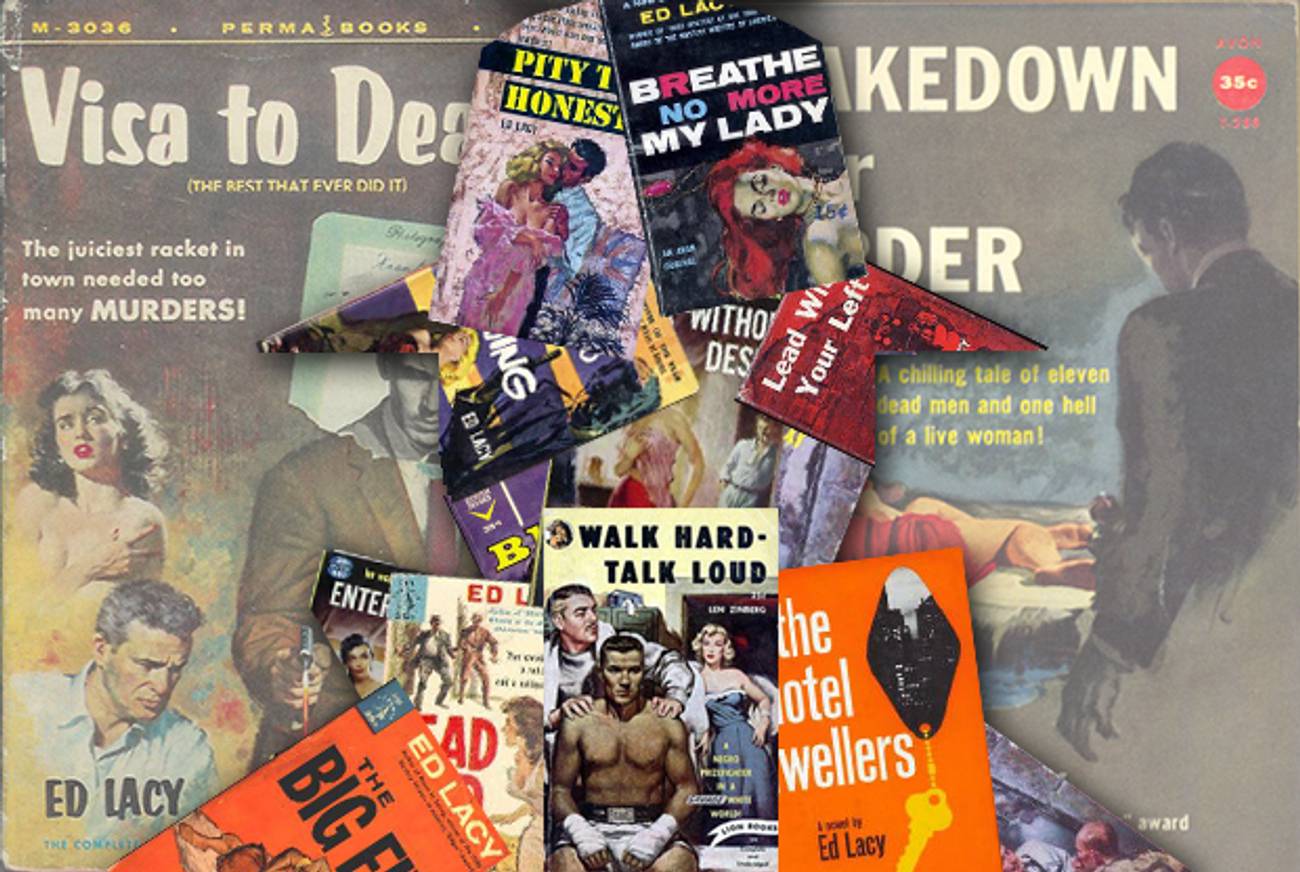

Ed Lacy, who died 45 years ago today, is as synonymous with the mystery paperback boom of the 1950s and 1960s as his contemporary Mickey Spillane. Like Spillane, Lacy was extremely productive (28 novels), successful (he sold 28 million copies, was translated into 12 languages, and received an Edgar Award), and favored big-breasted blondes and gory fisticuffs. Yet he was worlds away from the law-and-order anticommunist Spillane. In fact, Ed Lacy was the pen name of a proletarian writer and lifelong communist named Leonard Zinberg (1911-1968) who, before he became Ed Lacy, was a promising literary writer whose work appeared in The New Yorker, The New Republic (where he placed first in a Soldier’s Competition), and had published two acclaimed novels. The fact that the communist literati and the pulp-fiction king were in fact the same person was a closely guarded secret that very few fans of either man would have guessed at.

A Harlem resident his entire life, Zinberg was deeply interested in the plight of blacks. His first story, “Lynch Him” (1935), dealt with vigilante action against Southern blacks. His first novel, Walk Hard, Talk Loud (1940), about a black prizefighter, earned praise from Ralph Ellison. Drafted in 1943, Zinberg, as a Yank correspondent, continued his attacks on racism, even the anti-Japanese variety. By the late 1940s, Zinberg’s future as a major novelist seemed assured—until the blacklist era. A communist since the 1930s whose name appeared on the lists of at least three organizations deemed subversive by the attorney general, Zinberg was also vulnerable because he was married to a black woman who worked for the radical Jewish newspaper Die Freiheit. Zinberg wanted to both dodge the blacklist (he was so secretive about his identity that not even his literary agents knew that Lacy was a pen name) while at the same time continuing his attacks on racism.

Enter Ed Lacy, who debuted in 1950, arguably the height of the domestic Cold War, with the story “Curiosity Is Expensive” in the macho adventure magazine Man to Man. The story concerns a narrator who, lusting after his brother’s wife, hires a private investigator to research her past. The detective discovers that the woman in question once participated in a Depression-era robbery; she reveals that she did so because of an abusive boyfriend and economic deprivation. Even though the crime is 20 years old, the police arrest her, and her marriage falls apart. The story ends with the brother Al startling the narrator with such hate that he concludes that his life is in jeopardy. Read in light of Zinberg’s political background and the year, 1950, the story can be seen as a critique of the House Un-American Activities Committee’s investigation into the Depression-era politics of unfriendly witnesses. But it ends like a blacklistee’s fantasy: The victim fights back, psychologically damaging the instigator.

Attracted to the possibilities of noir, the Left thought they found their model proletarian writer in Raymond Chandler. But Chandler, a sturdy anticommunist, mocked their attempts; Philip Marlowe “has the social conscience of a horse,” he stated. In Lacy, they got what they hoped Chandler was and then some.

***

Lacy’s first attempts to address racism in his private-eye stories were labored. African Americans did not figure as clients or criminals but merely as downcast individuals that the protagonist passed on the street. A white cop’s black partner enters the novel Lead With Your Left only to tell the Italian-American not to be bothered by anti-immigrant slurs and then quickly leaves the story. It wasn’t until the Edgar Award-winning Room to Swing (1957) that Lacy seamlessly inserted antiracism into the genre through his black private eye, Toussaint Marcus Moore, a decorated war veteran and college-educated detective.

Toussaint, named by his father after the black revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, is in the vein of Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe. He smokes a pipe and is handy with his fist and wisecracks. But his skin color brings him into situations that the white private eyes never experience. A simple meal in a restaurant incurs the wrath of a white cop who “educates” Moore about segregation, while the white liberals in town are not violently repressive but are no less condescending:

“I always try to give you people a helping hand, so very frankly I was pleased when I learned you were a Negro.” The smile again, on the patronizing side this time.

Okay, whites can sure say the jerkiest things and I’d met her type before.

So then I knew they were going to bat “that boy” around, as one Negro writer calls this parlor game. I mean there’s a certain type of white who loves to get going on the Negro “question” or “problem,” in fact feels he must break out into a discussion whenever he’s around Negroes. I suppose talking about it is better than the attitude of most ofays who try to forget we’re alive. But it had been a long long time since I’d been in this type of bull session.

In his second Moore novel, Moment of Untruth (1964), the private detective goes to Mexico to solve a murder and ends up exposing an admired bullfighter for cowardice. Told there are “no color problems” in Mexico, Moore is treated as a white American but with an ironic twist: White Americans in Mexico are hatefully regarded as chauvinists, and Moore is no exception. Moore’s exposure of the bullfighter Cuzo results in Cuzo committing suicide. Although still hating him at novel’s end, Moore feels a racial solidarity with the bullfighter, who, as a pure Indian, was at the bottom of the Mexican racial hierarchy:

I knew he was a slave and only generations removed from slavery … he faced some of the same racism as I did in America. … I had a terrible feeling that I am an Uncle Tom doing the white folks a favor by knocking off Cuzo. I felt like I was betraying my color.

By the 1960s, Lacy would move away from the lone-wolf private eye encountering racism everywhere and into more localized novels with black police officers. In Harlem Underground (1965), Lacy introduced Lee Hayes, a rookie black cop and civil rights sympathizer. Hayes is assigned to go undercover in Harlem’s garment district to trap the Purple Eye killer. The killer seeks to pit blacks against Jews in order to revive Hitlerism. This theme of fomenting a race war between Jews and blacks was explored further with In Black and Whitey (1968). This time it is not an angry lone killer trying to revive Nazism, but a white police officer masquerading as a Jew. Even though Kahn is outed by a Jewish civil rights organizer, Lacy does not consider Jews immune to fascism. (As Anne, the organizer says, “One of Hitler’s worst beasts was named Rosenberg.”) After black-Jewish relations have calmed, the liberal establishment covers up Kahn’s real background and announces the peaceful resolution through the “all-American team of Negro-Jewish-Italian” cooperation. Once again, melting-pot liberalism is revealed as corrupt and ineffectual.

In the 1950s, the Communist Party line regarding race was that whites were inherently racist while minorities were not—hence white writers could not write about them in a nonracist manner. The life-long communist Lacy violated this dictum by having blacks capable of anti-Semitism and Mexicans constructing their own racial hierarchy. In his final novel, The Napalm Trumpet (1968), Zinberg even moved away from defending the Soviet Union toward a more ambivalent view of the Cold War by portraying the KGB as murderous as the CIA. But none of these sins was serious enough to attract the interest of the party’s censors.

Lacy also went against a key component of proletarian writing in his adherence to the aesthetic of noir. Proletarian novels always concluded on an inspirational note with the previously apolitical protagonist becoming radicalized and fighting the good fight. (Zinberg followed this dictum with his own contribution to the genre, Hold With the Hares [1948], where the Jewish sell-out Steve joins the cause, smuggling out a fugitive communist friend and starting a new life as a radical journalist.) Yet when Zinberg became Lacy, he apparently also found an aesthetic that appealed to him more. After years of apprehending criminals who commit crimes because they are starving, a disgusted Toussaint Moore leaves the PI business to become a mailman.

The larger irony of Zinberg’s own masquerade is that the Communist Party never figured it out. Otherwise, he might have suffered the fate of blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, who was pilloried by the CPUSA for “white chauvinism” because he wrote that a character was “dressed in his Sunday best.” But the party never denounced the mystery writer. Like Lacy’s readers, they apparently assumed that he was black.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ron Capshaw is a writer living in Midlothian, Va.

Ron Capshaw is a writer living in Midlothian, Va.