What are you reading? Post a comment and let us know.

Elisa Albert, Fiction Editor

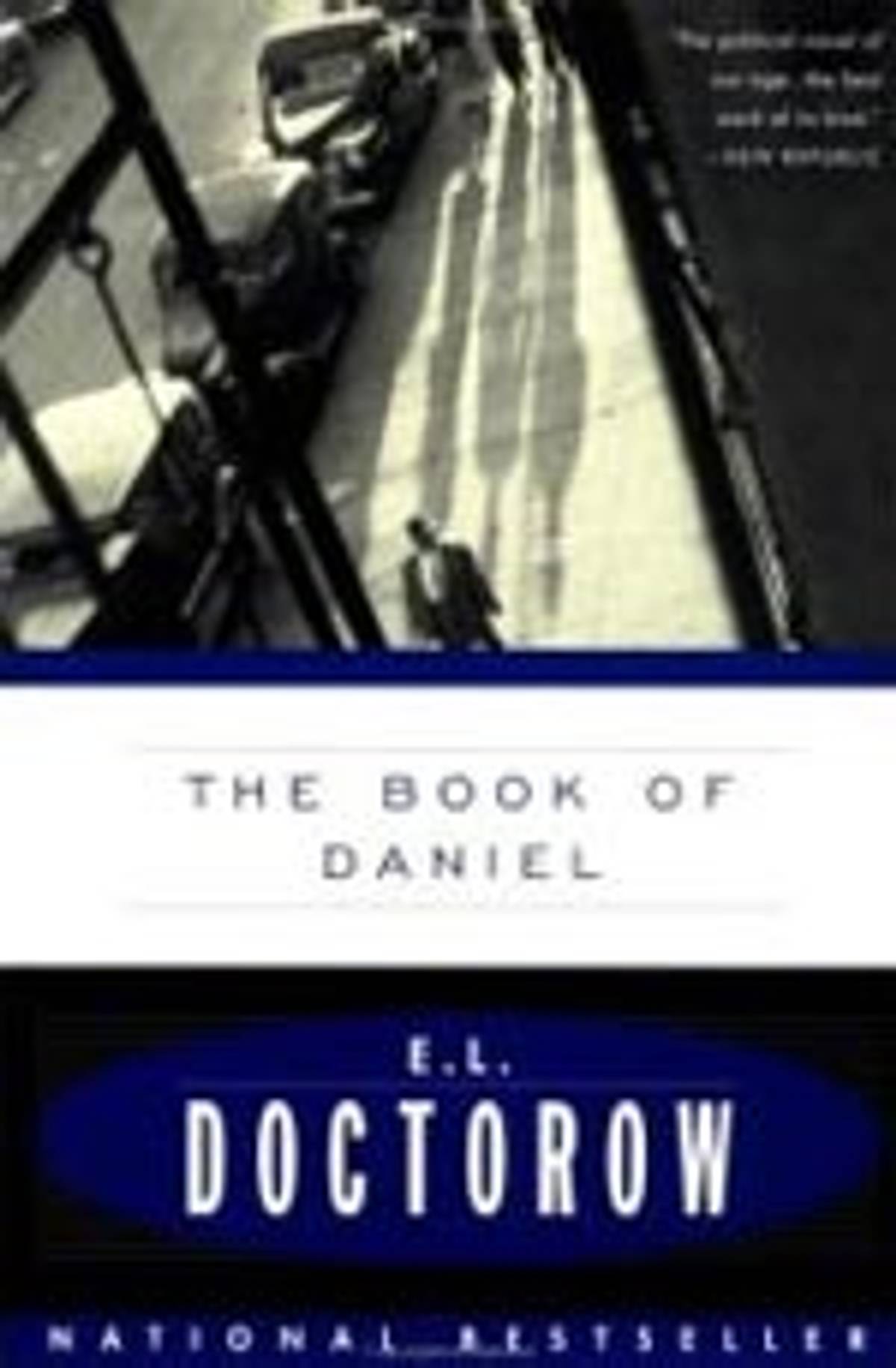

The Book of Daniel by E.L. Doctorow

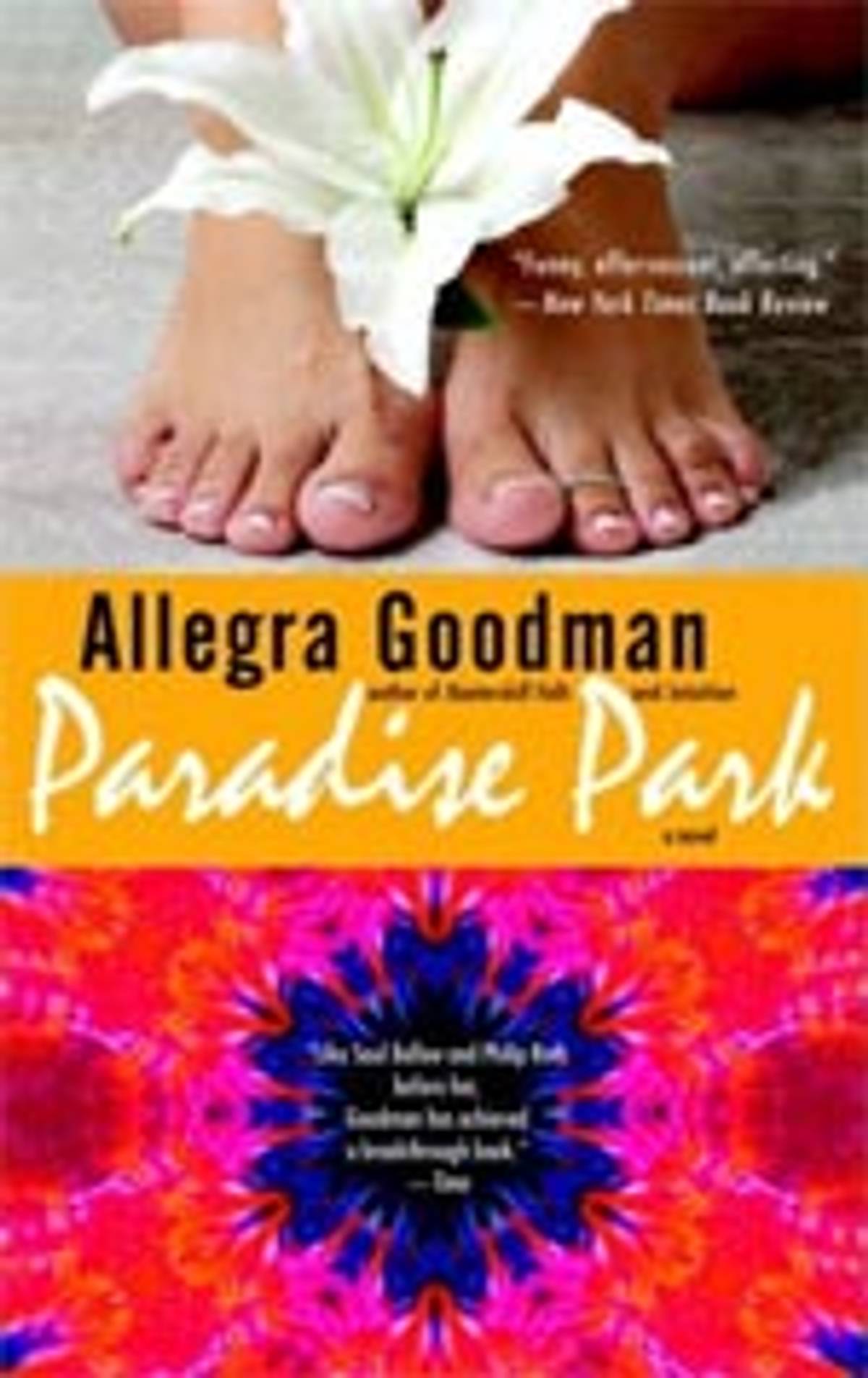

Paradise Park by Allegra Goodman

Hadara Graubart, Staff Writer

Lust in Translation by Pamela Druckerman

Growing Up Rich by Anne Bernays

Eve Grubin, Poetry Editor

Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice by Janet Malcolm

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot

Sara Ivry, Senior Editor

The Far Euphrates by Aryeh Lev Stollman

Sepharad by Antonio Munoz Molina

Lawrence Levi, Senior Editor

Teitlebaum’s Window by Wallace Markfield

In the Freud Archives by Janet Malcolm

Eryn Loeb, Associate Editor

The Red Leather Diary by Lily Koppel

What Are Big Girls Made Of? by Marge Piercy

Joanna Smith Rakoff, Editor in Chief

The Mandelbaum Gate by Muriel Spark

Thieves in the Night by Arthur Koestler

Julie Subrin, Podcast Producer

The Blessing of a Skinned Knee: Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children by Wendy Mogel

Red Cavalry by Isaac Babel

Ellen Umansky, Features Editor

Natasha by David Bezmozgis

The Collected Stories by Grace Paley

Elisa Albert, Fiction Editor

I’m reading: E.L. Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel is a rules-bending, walls-climbing, bets-off rollercoaster of a novel. Part rant, part political battle cry, part investigative odyssey, part lament, it jumps from first person to third person and back again. Daniel is the son of the fictional Paul and Rochelle Isaacson, an alternate-universe Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. He and his sister Susan were small children when their parents were arrested, imprisoned, questionably tried, and executed. And “his” book is a perhaps brilliant, perhaps insane attempt to make sense of his family’s fate—a book as full of furious intensity as its subject matter demands. “I suppose you think I can’t do the electrocution,” Daniel writes near the end, before a detailed account of his parents’ deaths. “I know there is a you. . . . YOU: I will show you that I can do the electrocution.” A wild, sometimes alarmingly unhinged ride.

I’m rereading: I barely glanced through Allegra Goodman’s Paradise Park when it came out in 2001. At the time, three hundred-plus pages about some messed-up flower child’s spiritual quest and eventual return to Judaism failed to engage me. Can’t say what led me to pick it up again; Sharon Spiegelman, the novel’s unlikely heroine, would likely appreciate this, given her mystical inclinations. Goodman is wonderful with plot in a way many contemporary literary authors are not; the novel goes places. Sharon’s journey spans twenty-odd years, taking her from a Hawaiian pot-farm to a Buddhist monastery to Crown Heights. It’s an engaging, thought-provoking, charming read. If the story’s resolution seems too pat, and Sharon’s family background a bit too easily skipped over, her narrative remains, simply, a joy. A novel this ambitious, this straight-shooting, and this full of life can, like the penitent soul, be forgiven a multitude of sins.

Hadara Graubart, Staff Writer

I’m reading: Pamela Druckerman’s Lust in Translation is that rare book that feels fun and naughty to read but is also thought provoking and thoroughly researched—and will make you a hit at dinner parties. In her investigation of attitudes toward sexual fidelity across cultures, Druckerman learns that the French are not as cavalier as she expected, that transgressive sexual behavior was a rare freedom under the repressive Soviet regime, and that, according to one Talmudic scholar, a husband should start to worry when his wife’s been alone with another man for “the time it takes a woman to remove a wood chip from her teeth.” (That one raises more questions than it answers.) While she never succeeds in finding the one comprehensive study that will illuminate worldwide sexual behavior, the anecdotal evidence she gathers is plenty provocative.

I’m rereading: Anne Bernays’s 1975 novel Growing Up Rich brings readers into the head of troubled, lonely teenager Sally Stern as she’s forced by tragic circumstances to move from New York City to Brookline, Massachusetts, to live with a family she hardly knows. She discovers that outside the Upper East Side, not all Jews share the view of their ethnicity that she had been raised with: “Presumably if you didn’t mention it, it would go away.” Set in the late 1940s, the book is full of delicious sociological details, such as a ritzy synagogue where yarmulkes are considered gauche, “like wearing the American flag on the seat of your pants to a DAR meeting.” Sally’s blunt insights are familiar—“Jews act differently with non-Jews . . . a slight readjustment of style, a change of emphasis”—and her bitter, scathing perspective is oddly endearing. I wonder why everyone knows The Catcher in the Rye but so few have read this equally captivating book.

Eve Grubin, Poetry Editor

I’m reading: Janet Malcolm’s Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice, a precise, elegant, and intellectually honest account of the lives of the poet and literary figure Gertrude Stein and her companion, Alice B. Toklas. Malcolm focuses on the time the two spent in France during World War II: How did two elderly Jewish lesbians living in Europe survive Hitler? She suggests in the beginning of the book that these women seemed indifferent to the plight of Jews during the Holocaust, identified themselves as elite, gentile European intellectuals rather than as the Jewish American expatriates that they were, and were professionally ambitious at all moral costs. (This internalized anti-Semitism and lack of care for fellow Jews reminds me of Simone Weil.) As always, Malcolm seems to be setting out to expose the dark emptiness beneath the glittery, pretentious surface of untouchable literary personalities.

I’m rereading: George Eliot’s last novel, Daniel Deronda, explores the tensions between English society and morality through the prism of Judaism and Zionism. While Eliot’s intellectual peers and the literary giants of her day were famously anti-Semitic, one finds in Daniel Deronda a deep respect for Orthodox Judaism and religious Jews (who play central roles in the novel), a critique of anti-Semitism, and an explanation of Zionism. (Reform Judaism, peripherally present, is rejected in the novel.) There’s a Shabbat meal that feels quite detailed and authentic, and the title character, an upper-class gentleman who discovers that his biological mother was Jewish, represents a morality that emanates from his faith.

Sara Ivry, Senior Editor

I’m reading: In a perversion of the adage to avoid judging a book by its cover, I have for some time found myself drawn to Aryeh Lev Stollman’s The Far Euphrates, with its titular suggestion of a distant desert land. As it turns out, it’s set not in Iraq but in Canada, and its plot concerns Alexander, a daydreaming boy who, in the years after World War II, grows into a young man among a tight-knit group that includes Holocaust survivors from Strasbourg. A rabbi’s only child, he’s viewed with circumspection by his unwell, emotionally removed mother, and as the prized hope of this tiny coterie, who’ve cobbled together emotional refuge from the collective wreckage of grief and disappointment. Employing a prose style that reminds me of both Death in Venice and Swann’s Way, Stollman deftly creates the intimate world of a child who discovers vulnerability and perseverance all around him.

I’m rereading: When I started reading Antonio Munoz Molina’s novel Sepharad by the ocean last summer, I thought it was as close as I would get to time travel. An unnamed narrator escorts the reader through a book that is part fiction, part history, and without traditional plot—an episodic voyage that often wades into stream of consciousness. The narrator drops in on European locales and real personalities (Kafka’s lover Milena Jesenska, for example) who endured the myriad tortures—genocide, fascism, exile—of recent history. Munoz Molina seeks to catapult the reader into a state of existential uncertainty: “When I travel I feel as if I were weightless, as if I had become invisible, that I am no one and can be anyone, and this lightness of spirit is evident in the movements of my body; I walk more quickly, with more assurance, free of the burden of my being.” This is not typical beach reading, certainly, but it transported me across the deep blue.

Lawrence Levi, Senior Editor

I’m reading: I’m halfway through Teitlebaum’s Window, Wallace Markfield’s uproarious 1970 novel set in Depression-era Brighton Beach, and I don’t want it to end. The protagonist is Simon Sloan, whom we meet as a child, “all rosy and redolent of matzo and milk,” and follow (so far) into adolescence. While his short-fused father and self-pitying mother bicker (“in Jewish,” Simon says), he seeks refuge with the Battle Aces, a tiny gang of smart alecks. Between movies, they torment patrons at Hebrew National and “squeeze tits” on Ocean Parkway; there’s a tour-de-force chapter-long circle jerk “on the Oriental rug” in one of their living rooms. Simon’s journal entries describe secret pride in his schoolwork, a burgeoning existential crisis, and a clash with his French-class crush, Clare Dushler: “You know what your main and basic trouble is? You’re not serious,” she declares. He replies, “Sure I’m not serious, how can I be serious, I’m Jewish.” That could easily be Markfield talking.

I’m rereading: The true story of Janet Malcolm’s In the Freud Archives is just as gripping and gasp-inducing the second time around. First published in 1984, it’s about a ferocious Oedipal struggle over Freud’s legacy. In the late 1970s the Sigmund Freud Archives’ founding director, K.R. Eissler, handpicked as his successor (with the approval of Freud’s daughter Anna) a brash, young Sanskrit scholar named Jeffrey Masson—a self-proclaimed “intellectual gigolo” who, after gaining access to restricted letters, became determined to prove the spuriousness of Freud’s main theories. That Eissler, perhaps the most revered psychoanalyst of his era, could be seduced by Masson (“Even my own secretary warned me about him,” Eissler says) is one of the book’s many mysteries. The NYRB Classics edition features an afterword, written by Malcolm in 1996, describing Masson’s subsequent libel lawsuit against her and the book’s publisher; it lasted ten years.

Eryn Loeb, Associate Editor

I’m reading: For five years beginning in 1929, Florence Wolfson was a faithful diarist, penning nearly two thousand entries without ever skipping a day. In 2003, writer Lily Koppel found Florence’s crumbling diary in a Manhattan dumpster. Bewitched by its strangely familiar contents, she pored over brittle pages that recounted the young woman’s longings, literary aspirations—which involved hosting a salon attended by the likes of Delmore Schwartz—and her burgeoning sexuality. The Red Leather Diary reconstructs Florence’s biography through these original entries and Koppel’s own interviews with Wolfson, now in her nineties. Florence’s voice, steeped in the legendary New York of the 1930s, would be compelling enough on its own, but it’s intensified by her bittersweet reunion with her old diary, and the reminder that there are treasures hidden among the city’s castoffs.

I’m rereading: Marge Piercy’s poem “Maggid” is a staple of my family’s Seder, and this year it sent me searching my shelves for her 1997 collection What Are Big Girls Made Of? What the book lacks in subtlety, it makes up for in fierceness. Classically feminist poems that take on sexual harassment and torturous beauty standards are offset by more restrained meditations on love and aging: The sensual, climactic “The Art of Blessing the Day” finds Piercy reflecting on “the discipline of blessings,” and “Coming Up on September” captures the ambivalence that accompanies the passage of time. In the new year, she writes, “I will find there both ripeness and rot, / what I have done and undone, / what I must let go with the waning days / and what I must take in.”

Joanna Smith Rakoff, Editor in Chief

I’m reading: With the sixtieth anniversary on my mind, I’m turning to a couple of rarely read British novels that examine earlier, but no less turbulent, periods in Israel’s history, while laying bare the anti-Semitism of Britain’s upper classes. Published in 1965, on the heels of her bestsellers The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and Girls of Slender Means, Muriel Spark’s odd, elliptical The Mandelbaum Gate awed critics but baffled fans. Set in Jerusalem, in 1961, during the Eichmann trial, the novel follows Freddy Hamilton, a mid-level British diplomat, and Barbara Vaughan, the prim, Bible-quoting schoolteacher for whom he falls (never mind that she’s in Jerusalem to meet up with her fiancé, an archaeologist unearthing the Dead Sea Scrolls in Jordan). The trouble is that Vaughan—like Spark herself—is half-Jewish and, thus, prohibited from crossing the titular gate into Jordan. It’s not giving too much away to say that she does so anyway and Spark’s melancholic, character-driven tale turns into an espionage novel, complete with costumed escapes and desert hideaways. Thrilling stuff, sure, but there’s more at play: difficult questions of ethnicity, identity, and faith.

I’m rereading: More difficult, however, are the ethical conundrums at the heart of Arthur Koestler’s fierce, brilliantly observed 1946 novel Thieves in the Night, which chronicles the establishment, in the late 1930s, of a kibbutz on land purchased from the mukhtar of an Arab village. Like Barbara Vaughan, Koestler’s hero, Joseph, is a bookish, half-Jewish Briton, which makes him an anomaly among his fellow settlers, the “phlegmatic and sturdy Sabras”—farmers’ sons “haunted by no memories”—and the new immigrants from Europe, whose “faces were darker, narrower, keener; already, they bore the stigma of things to forget.” As Britain turns away shipload after shipload of refugees and the younger generation of local Arabs grows increasingly radicalized—gorily murdering Joseph’s closest friend—quiet, apolitical Joseph finds himself drawn to a radical offshoot of the Haganah, regarded as “fascist” by the pacifist members of his commune. Joseph is a character of tremendous complexity, but Koestler inhabits his secondary characters—from the kind mukhtar and his dimwitted son to a host of British officials and a gung ho American journalist—with equally perfect pitch.

Julie Subrin, Podcast Producer

I’m reading: I am now “with child,” and in the few months I have left before all hell breaks loose, I’d like to read Wendy Mogel’s The Blessing of a Skinned Knee: Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children. The book, published in 2001, is a best seller regularly foisted upon new mothers, and the title is, admittedly, cloying. But from what I can tell, Mogel does not engage in psychobabble, or Bible-babble. She worked for fifteen years as a child psychologist, and before writing the book spent several years immersed in Talmud and Torah study. Her ultimate advice, it seems, is pretty straightforward: Don’t coddle your children. Your job is not to cultivate happiness, but rather, in her words, “honesty, tenacity, flexibility, optimism, and compassion.” In the near future, I’ll probably be more focused on cultivating a good night’s sleep, but I wouldn’t mind getting a head start on the bigger stuff.

I’m rereading: The writing in Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry stories, written after he served with the Red Army in 1920, is sneaky. Things unfold quietly, with turns of violence so sudden you have to read the story again to see what you missed the first time. In “Crossing the Zbrucz,” he begins with a lush landscape along the curves of a misty river, and then tosses in this little grenade: “An orange sun is rolling across the sky like a severed head.” In the same story, it’s not until the middle of the night that the narrator, a soldier billeted in a ransacked Jewish home, realizes he’s been sleeping next to an old man eviscerated by Polish forces. Again, no warning, and no explicit judgment. Babel forces you, over and over, to fend for yourself—to read vigilantly, only then discovering the pathos buried underneath.

Ellen Umansky, Features Editor

I’m reading: I still remember being floored by David Bezmozgis’s short story “Tapka” when I first read it in The New Yorker years ago. It’s a wonderfully dark, unsentimental tale of how a young Latvian immigrant becomes complicit in the near-murder of his neighbor’s beloved dog. Somehow, though, I’d never read Bezmozgis’s story collection, Natasha, in full. It follows the Bermans—Roman, Bella, and their only child, Mark—as they struggle to adapt to post-Soviet life in Toronto. “This was 1983, and as Russian Jews, recent immigrants, and political refugees, we were still a cause,” Bezmozgis writes in “Roman Berman, Massage Therapist,” a story that expertly illuminates the humiliations (some minor, some major) that recent arrivals endured. Bezmozgis has a keen sense of story that short fiction can often lack, and his spare prose is attuned to the ironies and moral dilemmas of everyday life—qualities that also characterize the rich accounts he’s written for Nextbook.

I’m rereading: I first read Grace Paley’s stories in college, and they so struck me that I feel some trepidation in returning to them—what if they don’t measure up to my memories? Paley, the daughter of Ukrainian immigrants, captures the stories and rhythms of the world in which she grew up in lean, Yiddish-inflected prose, at turns lyrical, surprising, and wholly her own. “I was popular in certain circles,” is how the inimitable narrator of “Goodbye and Good Luck” introduces herself. “I wasn’t no thinner then, only more stationary in the flesh.” The elliptical stories Paley wrote from the ’50s to the ’80s—available in one volume, The Collected Stories—don’t shy away from larger disappointments (marriages are always unraveling, politicians are constantly disappointing), but one is left with a feeling of possibility, in storytelling and beyond. “Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life,” she writes.