Surrender or Die

A gripping new history of Flavius Josephus portrays a Roman Jewish writer forever wrestling with his identity

The choice between a Jewish life and a life in the world is one that no longer exists for American Jews. When observant Jews can run for vice-president, or star in a popular sitcom, or serve as Secretary of the Treasury, there is no need to undertake the neurotic role-playing of being “a man in the street, a Jew at home.” But for most of Jewish history, things have not been so easy. For a Judean in the 3rd century BCE, entrance to the exciting modern world of gymnasiums and philosophical education came at the price of sacrificing to the Greek gods. So too for Jews in 19th-century Germany, who often felt, in the words of Heinrich Heine, that baptism was the “admission ticket to European culture.”

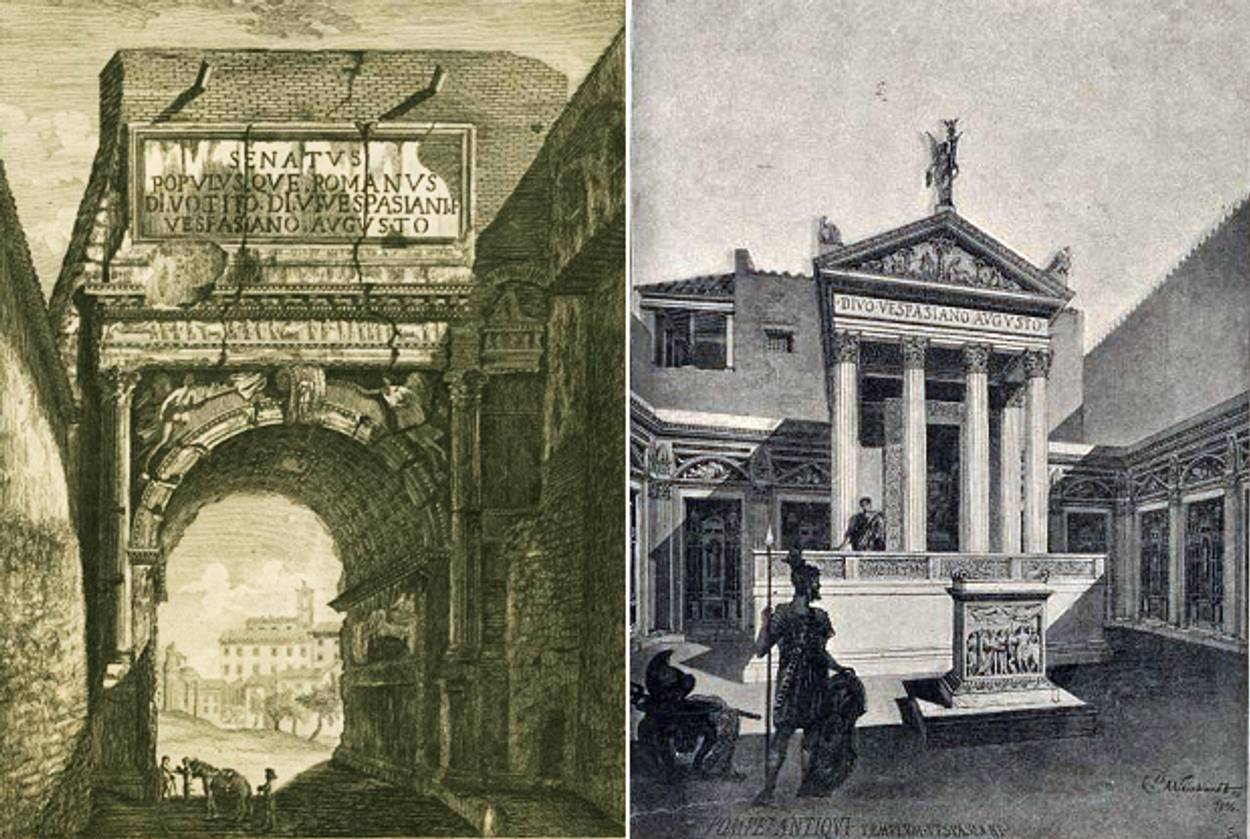

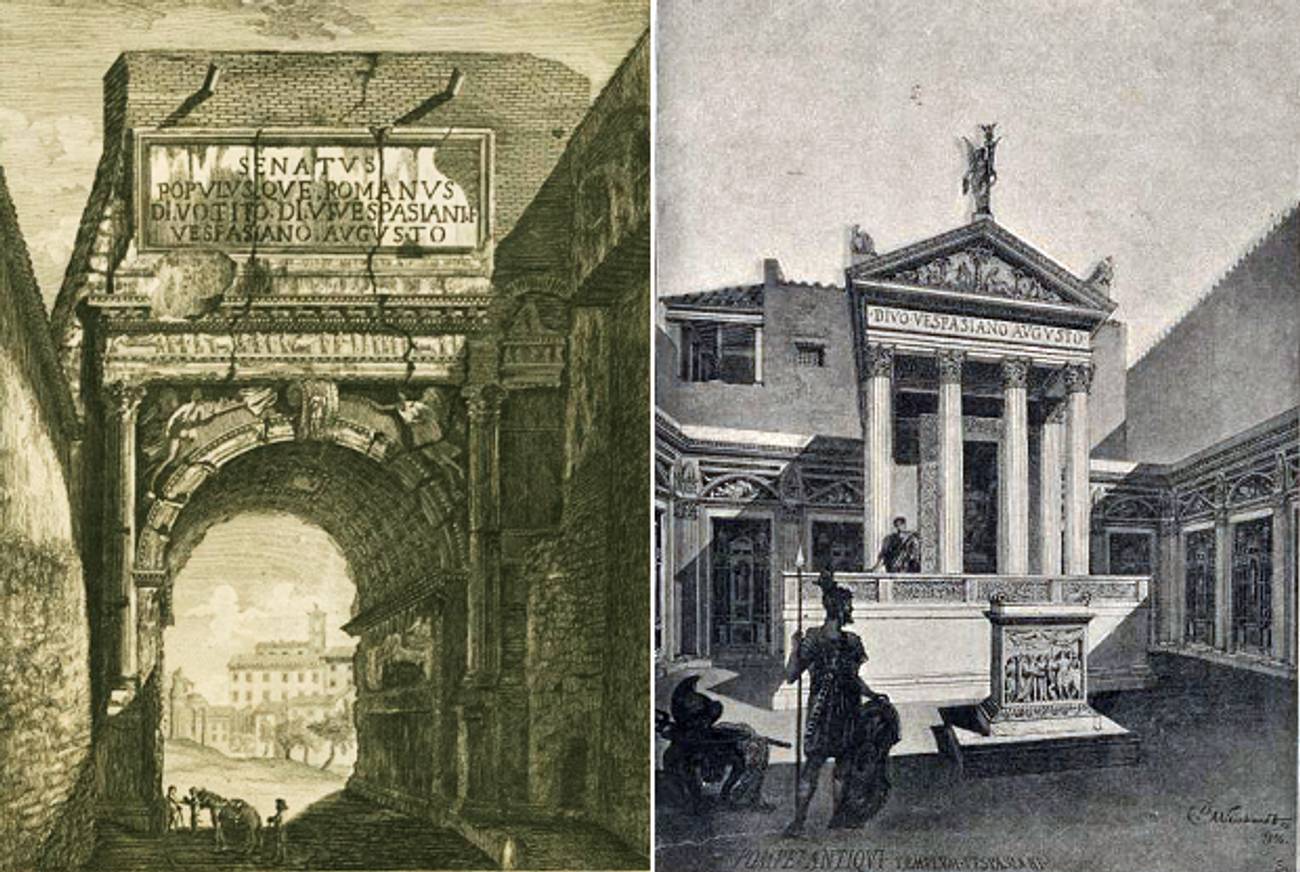

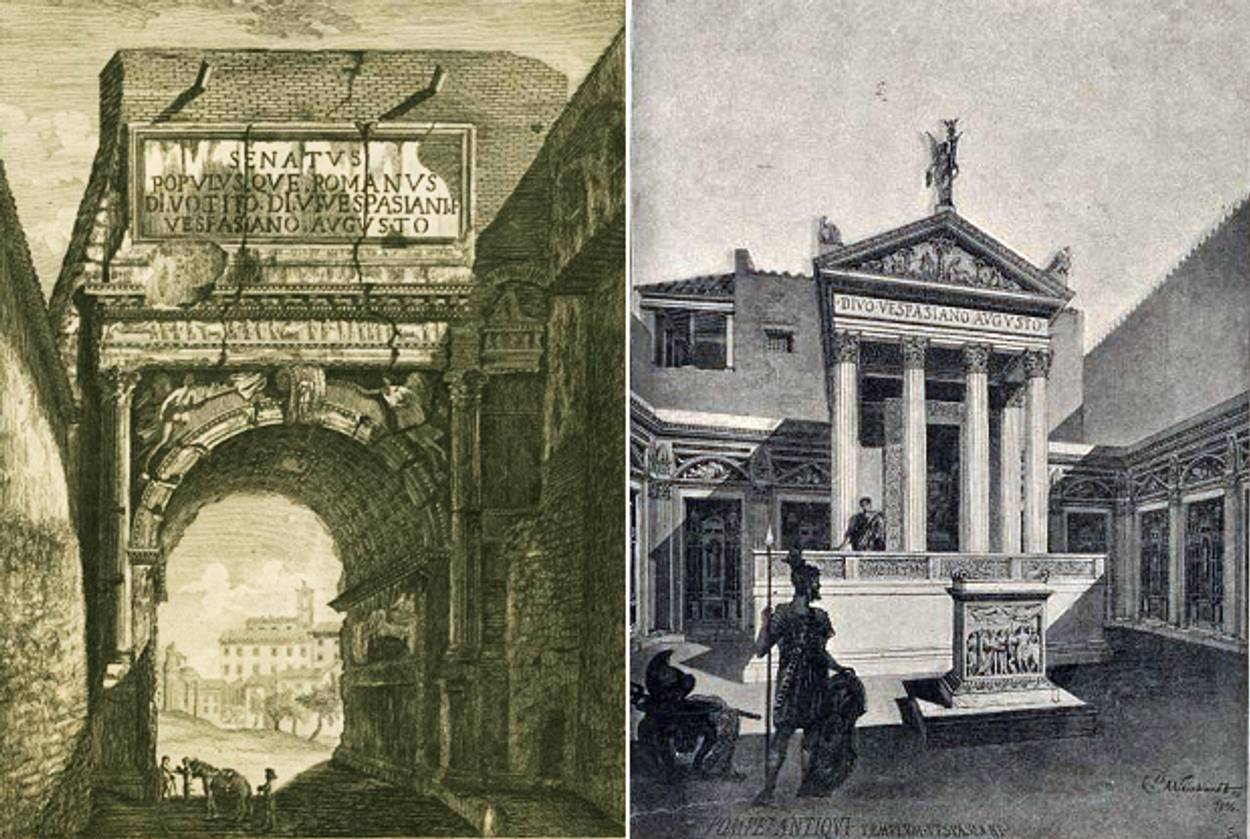

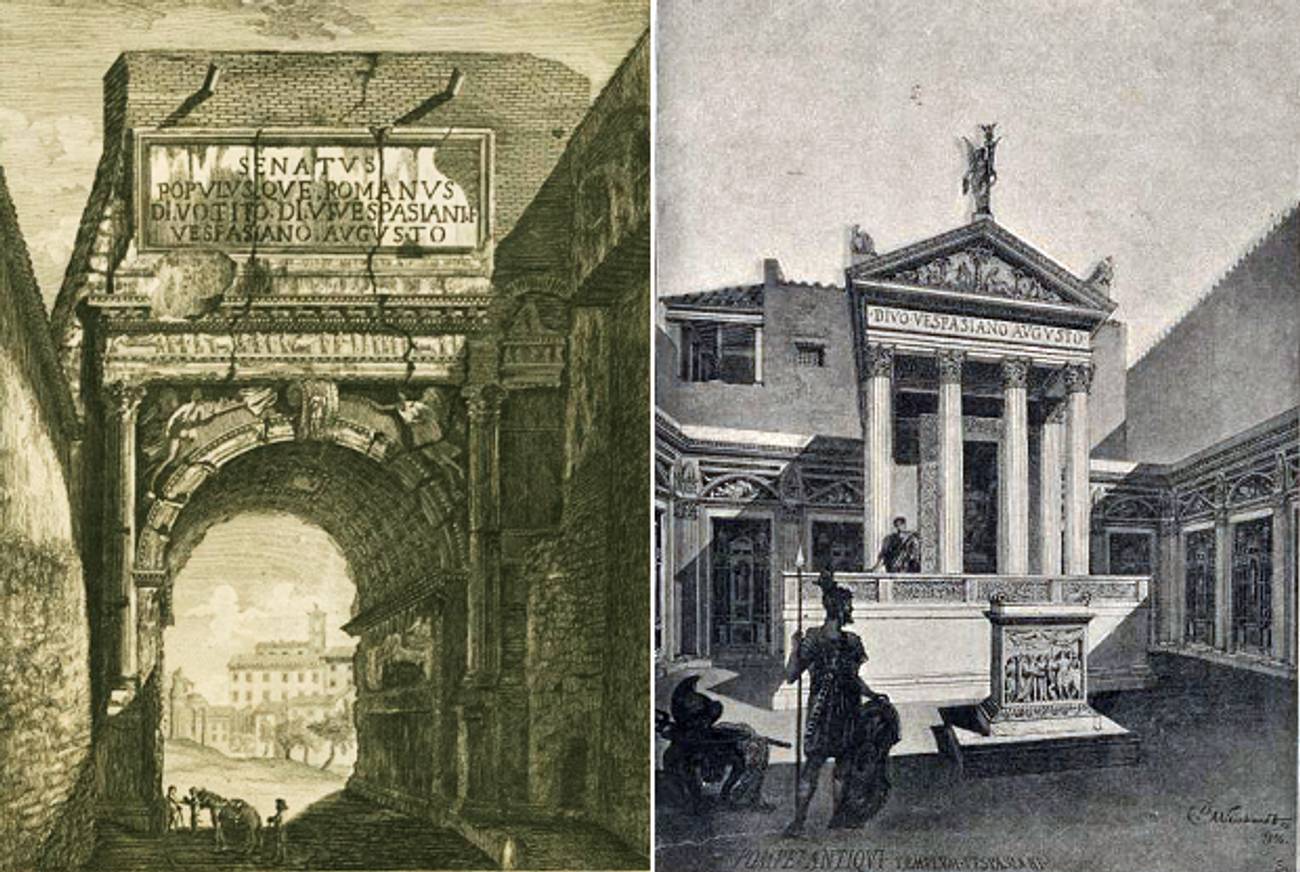

In A Jew Among Romans, the English writer Frederic Raphael examines one of the most famous cases in history of a Jew torn between his identity and his ambition. This is the man who was born Joseph ben Mattithias, but who is remembered as Titus Flavius Josephus, the author of The Jewish War—the only surviving account of the war between Rome and Judea that led to the destruction of the Second Temple and the beginning of the Diaspora. The change in his name itself tells a story: Starting out a member of a distinguished priestly family in Judea, Joseph ended his life in the entourage of the emperor in Rome. Yet the journey that took him there was so ethically dubious that Jews ever since have regarded him with suspicion. Raphael quotes like a refrain the verdict of the Israeli archeologist Yigael Yadin that Josephus was a great historian and a bad Jew; and his own book can be seen as a meditation on what it might mean to be a bad or good Jew, and whether it matters.

Thanks to The Jewish War and his other Greek-language writings—including the “Vita,” which may count as the earliest surviving autobiography—we know more about Josephus than virtually any person of his age. He was born in 37 CE, in a Judea boiling with political and religious tension. It was the era not just of Jesus, but of the monastic Essenes, a desert sect that looked forward to the end of days, and of bitter theological disputes between Pharisees and Sadducees. Political control of the province was divided between a local king, Roman-appointed officials, and the priestly hierarchy, all of whom pursued their conflicting interests. Raphael’s account of their intrigues is perhaps excessively detailed, but it convincingly gives a sense of a world where survival, not to mention flourishing, required a certain suppleness.

This quality Joseph ben Mattithias clearly possessed. In his late twenties, he was part of a delegation chosen to go to Rome to intercede with the emperor on behalf of some imprisoned Jewish priests. En route, his ship sank in the Adriatic, and Joseph was one of just a few survivors—a foretaste of the ambiguous good luck that would follow him all his life. Once in Rome, he had the chance to experience the culture and material delights of the wider Roman world, whose sophistication would surely have enthralled a provincial. This early visit, Raphael suggests, made him a natural go-between, capable of bridging Roman and Jewish cultures.

This was, however, a dangerous skill to possess at a time when relations between Judea and the Roman Empire were approaching a crisis. By the time Joseph returned to his home country, Judea was in open revolt against Rome, after a series of provocations by local officials had ignited the fury of the young Jewish fundamentalists known as Zealots.

***

Raphael follows Josephus in making clear that the Jewish War was, first of all, a civil war, in which the Zealots forced the more cautious priests and elders into a conflict that the Jews could never win. Meanwhile, freelance warlords roamed the countryside, extorting and looting. Raphael absolutely declines to see the Jewish War as a noble national uprising against foreign rule, or a religious movement to preserve the sanctity of the Temple, as various Jewish historians have seen it. For him, it is a sordid power struggle, driven by fanaticism, which ended in inevitable catastrophe.

This was very much Josephus’ view as well. “Joseph insisted,” Raphael writes, “that the tenets of Judaism in no way required that he and the best people in Jerusalem should sacrifice their lives rather than endure patiently.” It was perhaps in the hope of brokering a peaceful solution that he accepted an appointment as a general in the Jewish army, in charge of the Galilee. During his brief command, he had his hands full keeping the peace among various Jewish factions, who frequently threatened his life. In one episode, he silenced a mob by having its leaders flayed alive, then throwing the bloody bodies into the street—and this was even before the Romans, the nominal enemy, appeared on the scene.

When the Roman army arrived, under the command of the future emperor Vespasian, Joseph lodged his troops in the town of Jotapata, north of Nazareth, hoping that the legions would detour around him and continue on to Jerusalem. But Vespasian, as Raphael makes clear, was in no hurry to win a splendid victory; generals who did tended to fall afoul of the emperor, Nero, whose insane vanity would brook no rivals. So, the Romans laid siege to Jotapata, in a fight Josephus describes in fascinating detail. A key problem for the besieged Jews was water, since there was only one spring inside the city. Cunningly, Joseph “ordered some of the garrison to soak their outer garments and hang them over the battlements until the walls ran with water”—hoping to convince the Romans that men who would waste water in this way could not be too short of it.

Finally, inevitably, the Romans made their assault and breached the walls of the town. Joseph and about 50 other Jews took refuge in a cave, where they were soon discovered. They were left with a terrible choice: Should they surrender to the Romans, who were not known for their mercy to rebels, or take their own lives and die as martyrs? For what happened next we have only Joseph’s own account. First he tried to convince his fellow Jews that they should live, that it would be a sin to commit suicide: “Do you suppose that God is not angry when a man treats His gift with contempt?” he records himself asking.

But this argument failed to convince, whereupon Joseph suggested that they take turns killing one another, drawing lots to determine who would kill who. By either a miracle, another stroke of very good luck, or some sordid scheming, Joseph ended up as one of the last two Jews alive—whereupon he decided not to die after all, but to go ahead and surrender to the Romans.

To secure his good treatment, he came up with a brilliant stratagem. He announced to his captor that the God of the Jews had vouchsafed him a prophecy that Vespasian would end up as emperor of Rome. This is the most dramatic, and ethically problematic, moment in Joseph’s whole story, and Raphael, whose works for the screen include Two for the Road (1967) and Stanley Kubrick’s posthumous Eyes Wide Shut (1999), relishes it. “From the moment when he’d crossed the lines,” Raphael observes, Joseph—or, as he would now become, Josephus—had “committed himself to being a performer. No longer a Jew among Jews, he was conditioned by his alien audience: it played with him; he played to it. He was, in a literal and theatrical sense, cast among strangers.”

By making Vespasian such a loaded promise, Josephus turned himself into an indispensable man. Vespasian was not yet openly striving for the purple, but Josephus was telling him something he desperately wanted to hear. At the same time, by listening to the prophecy, Vespasian was more or less committing himself to rebellion against Nero. The emperor and the Jew were locked in a conspiratorial embrace. Fortunately for Josephus, his prophecy came true. Even as Vespasian’s son Titus completed the destruction of the Temple and the conquest of Judea, Vespasian himself marched on Rome and seized the throne.

***

For the rest of his life, Josephus would be an imperial hanger-on in Rome. He took his new names, Titus Flavius, in honor of the new emperor—that is, of the man who had destroyed his country. Yet he spent his time in Rome writing books in defense of Jews and Judaism, if not quite of the Jewish uprising. “Throughout his career,” Raphael writes, “Josephus remained a polemic pamphleteer in defense of Judaism.” His Jewish Antiquities retold the stories of the Hebrew Bible for foreign consumption, while his Against Apion was a passionate tract against a leading anti-Jewish writer.

Josephus remained between the two cultures, no longer trusted by Jews, never fully accepted by Romans. For Raphael, this is what makes him an exemplary Jewish figure. He is the patron saint of the modern Jewish intellectual, the writer or journalist who turns to the page to create the identity he can’t find in life: “For the Jewish intellectual, especially once he repudiates—or no longer has access to—community, the blank page becomes his only inalienable territory.” This is arguable as a matter of historical fact—despite Raphael’s frequent assertions, Josephus is hardly the first Jewish writer, nor would he have had the modern concept of what it means to be an intellectual.

But it is a useful conceit for Raphael’s book, especially its last third, which takes a leisurely tour through subsequent Jewish history, lighting on figures whom Raphael finds Josephan—Spinoza, Freud, Wittgenstein. There is nothing very original in this praise of the alienated Jewish intellectual, or deeply learned in Raphael’s case studies; often this section reads as though a well-stocked mind has simply been emptied out onto the page. (A large number of Raphael’s examples and sources come from books published in the last few years, including Hillel Halkin’s Nextbook biography of Yehuda Halevi.)

Still, there is a certain charm in the free-associative footnotes, which are full of civilized trivia: e.g., “Until very recently, applications for membership of country clubs and golf clubs, in Britain and the United States, routinely demanded that the candidate declare ‘name of father, if changed.’ ” In the end, it is tempting to see Raphael’s study of Josephus less as a historical biography than as a kind of self-portrait, of a Jewish writer forever wrestling with his identity: “Josephus, the exile, the traitor, the witness, the reasonable patriot, the pious Jew, the alienated solitary, the sponsored propagandist, melts into and disappears into his textual persona as if it were an alibi. Words supply his coat of many colors.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.