Susan Sontag Tells All

The newly published second volume of the great critic’s journals reveals her transformation from hedonistic revolutionary to elitist enforcer

It would be hard to find two writers with less in common than Cynthia Ozick and Camille Paglia. Ozick the owl is wise, serious, modernist, and devoted to literature; Paglia the peacock is flashy, provocative, postmodernist, and celebrates pop. Put them in a room together and they would probably have nothing to talk about. Except, perhaps, for one thing: their profoundly ambivalent feelings about Susan Sontag. Both Ozick and Paglia have written essays describing their own private agons with Sontag and everything she represented, especially to other women writers, in the 1960s and 1970s.

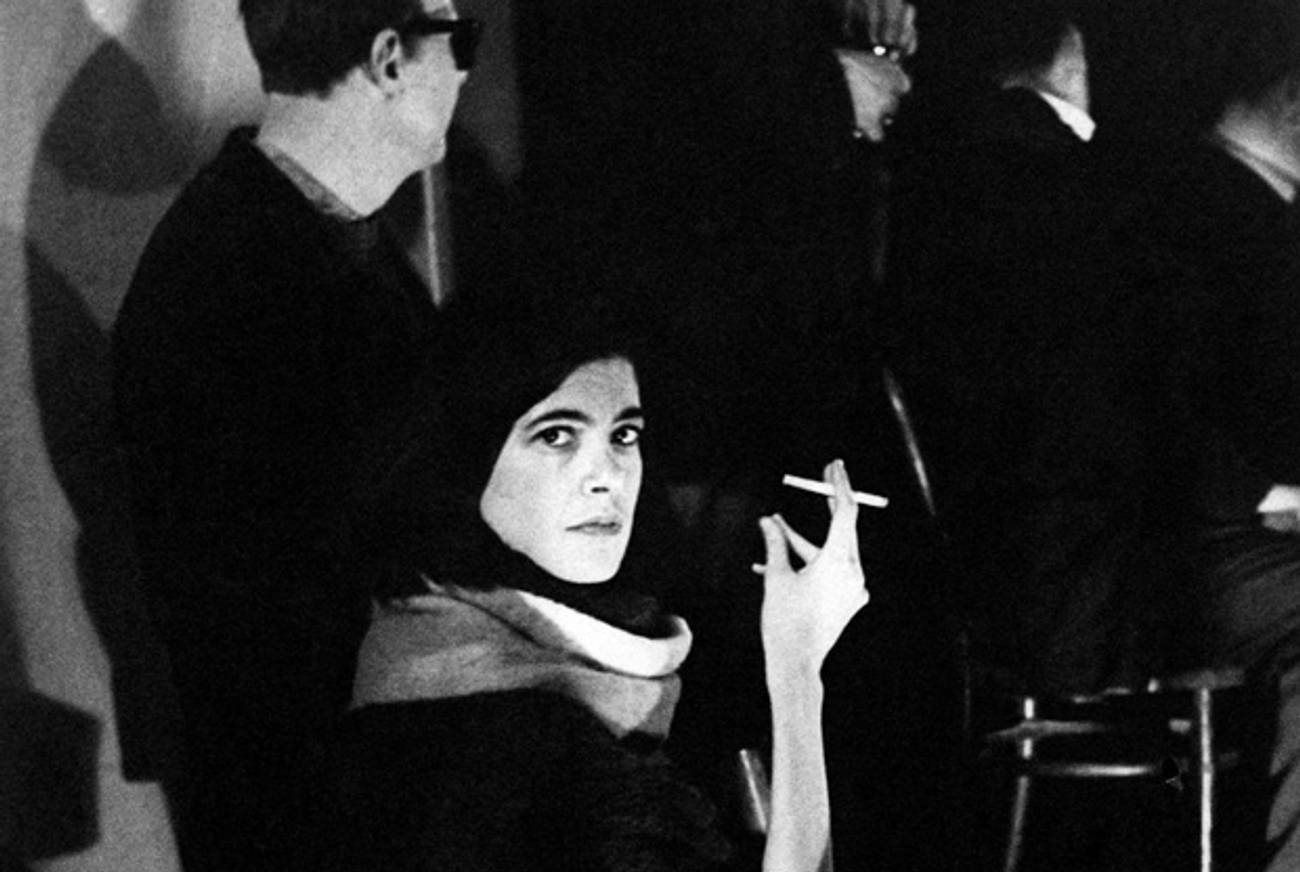

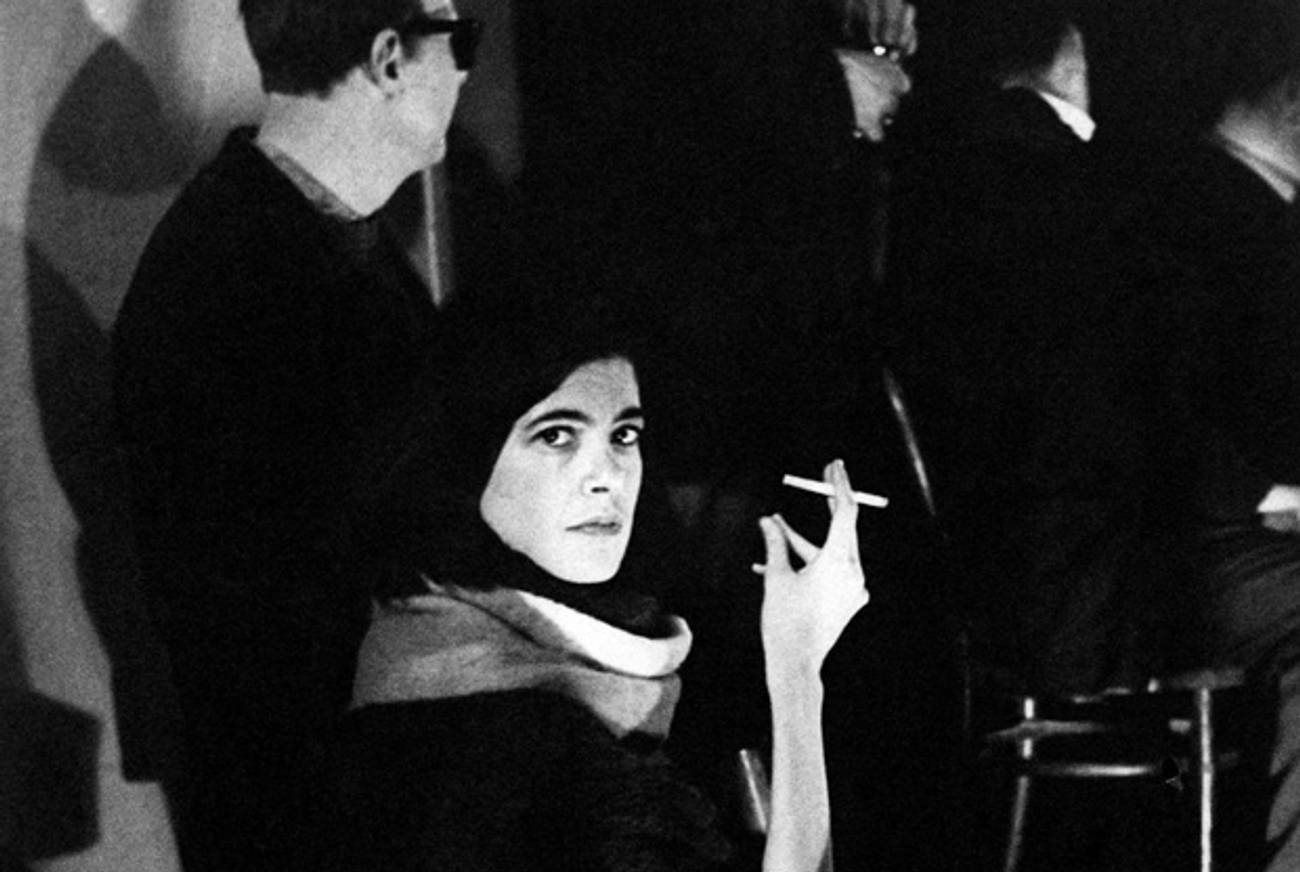

Ozick’s essay “On Discord and Desire” was written in response to Sontag’s death in 2004 (it can be found in her book The Din in the Head), and it begins with a reflection on Sontag’s image, as it appeared on “the back cover of my browning paperback copy of The Benefactor, [Sontag’s] first novel published in 1963, when she was thirty: dark-haired, dark-browed, sublimely perfected in her youth.” The image is an appropriate, even inevitable starting place for a consideration of Sontag, not because her image was her main achievement or primary concern, but because so much of her power as a cultural figure came from what she was seen to represent.

As Ozick sees it, when Sontag published her landmark essay collection Against Interpretation in 1966, she fired the first shot in what would become the 1960s revolution in taste and standards. When Sontag declared, “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art,” she issued what sounded to Ozick like a “summons to hedonism” and a “denigration of history.” Sontag’s name became a battle cry, which stood for “fusion rather than separation, it meant impatience with categories, it meant infinite appetite, it meant the end of the distinction between high and low.” And to Ozick, who at the time was laboring away in obscurity in the Bronx, Sontag seemed to speak with all the authority of the Zeitgeist itself: “She was the tone of the times, she was the muse of the age, she was one with her century.” When Ozick looks at that photo of Sontag, she sees the stylish barbarism of the sixties in a single alluring image.

Turning from Ozick’s Sontag to Paglia’s Sontag, however, is a weird, Rashomon-like experience. For in “Sontag, Bloody Sontag,” Paglia’s slashing, self-regarding attack (it can be found in her essay collection Vamps and Tramps), what angers her most about Sontag is precisely her dull, old-fashioned seriousness. Paglia, too, begins by remembering Sontag’s “glamorous dust-jacket photo,” which “imprinted [her] sexual persona as a new kind of woman writer so indelibly on the mind.” But by the time Paglia met her idol, when she arranged for Sontag to speak at Bennington College—an event that turned into a memorable fiasco—she found Sontag a different person from the one she had expected.

Ironically, what infuriated her is that Sontag was not the hedonistic leveler Ozick imagined, and that Paglia herself had admired. “I grew more and more aggravated by her arch indifference to everything she had glorified in Against Interpretation,” Paglia writes. “Sontag’s calculated veering away from popular culture is my gravest charge against her.” She was particularly appalled by Sontag’s declaration, in a Time magazine profile, that she didn’t own a television: “Not having a TV is tantamount to saying, ‘I know nothing of the time or country in which I live,’ ” Paglia scoffs.

The strange thing is that Ozick and Paglia were both right about Susan Sontag. At the beginning of her career, she was a revolutionary and a hedonist and a leveler; by the end, she was an elitist and an enforcer of literary and cultural hierarchies. You can see the transformation neatly encapsulated in the paperback edition of Against Interpretation, which comes with an afterword Sontag wrote in 1996, on the 30th anniversary of the book’s publication. In the title essay, the 31-year-old Sontag inveighs against the mind in Blakean terms: “In a culture whose already classical dilemma is the hypertrophy of the intellect at the expense of energy and sensual capability, interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art. Even more. It is the revenge of the intellect upon the world. To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world—in order to set up a shadow world of ‘meanings.’ ” Instead of meanings, she calls for “transparence,” for “new sensory mixes,” for sheer experience cut loose from the need to interpret, analyze, and moralize: “A work of art encountered as a work of art is an experience, not a statement or an answer to a question. Art is not only about something; it is something.”

Yet in the afterword, the 63-year-old Sontag sounds a Prufrockian note: That is not what she meant, at all. “In writing about what I was discovering,” she now realizes, “I assumed the preeminence of the canonical treasures of the past. The transgressions I was applauding seemed altogether salutary, given what I took to be the unimpaired strength of the old taboos.” But in fact, those taboos were like a house eaten up by termites, ready to collapse at the first push. “What I didn’t understand (I was surely not the right person to understand) was that seriousness itself was in the early stages of losing credibility in the culture at large,” Sontag writes in 1996. “Barbarism is one name for what was taking over. Let’s use Nietzsche’s term: we had entered, really entered, the age of nihilism.”

In fact, a close look at the evolution of Sontag’s writing shows that it did not take her half a lifetime to start regretting, or at least rethinking, Against Interpretation. Take, for instance, the development of her views about Leni Riefenstahl, the director whose films glorifying Nazism are among the greatest works of propaganda ever made. In Against Interpretation, Sontag went out of her way to praise these films on aesthetic terms: “To call Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will and The Olympiad masterpieces is not to gloss over Nazi propaganda with aesthetic lenience. The Nazi propaganda is there. But something else is there, too, which we reject at our loss.” For a Jewish writer publishing in Partisan Review—for decades the Bible of scrupulous anti-totalitarians—this was a carefully chosen heresy. It was meant as a concrete example of Sontag’s elevation of the aesthetic over the ethical, of “sensory mixes” over what she called, contemptuously, the Matthew Arnold school of moral journalism.

It was an unmistakable recantation, then, when Sontag published the essay “Fascinating Fascism,” which is collected in her 1980 volume Under the Sign of Saturn. For in this celebrated piece, she writes thoughtfully and indignantly about the rehabilitation of Riefenstahl. She exposes the way Riefenstahl rewrote her C.V. to minimize her profound Nazi ties and links her late-life photographic portraits of African tribesmen to her earlier fascist glorification of the body and violent struggle. But most of all, Sontag decries the way Western intellectuals and connoisseurs have been complicit in this rehabilitation. The author of “Notes on ‘Camp’ ” blames this moral dereliction on “the sensibility of camp, which is unfettered by the scruples of high seriousness: and the modern sensibility relies on continuing trade-offs between the formalist approach and camp taste.”

More, Sontag detects a subterranean connection between fascism, with its celebration of irrationality and community, and the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s, which valued the same things. Thus “a fair number of young people now prostrating themselves before gurus and submitting to the most grotesquely autocratic discipline are former anti-authoritarians and anti-elitists of the 1960s.” By the end of “Fascinating Fascism,” Sontag concludes that when it comes to culture, quod licit Jovi non licit bovi:

Art that seemed eminently worth defending ten years ago, as a minority or adversary taste, no longer seems defensible today, because the ethical and cultural issues it raises have become serious, even dangerous, in a way they were not then. The hard truth is that what is acceptable in elite culture may not be acceptable in mass culture, that tastes which pose only innocuous ethical issues as the property of a minority become corrupting when they become more established.

Indeed, it’s possible to see this dilemma—the balancing of the claims of ethics with those of aesthetics—surfacing even earlier in Sontag’s career. Her second collection of essays, Styles of Radical Will, appeared in 1969, at the height of the sixties’ turmoil, and probably the best-known piece in it is “What’s Happening in America” (1966). This originally took the form of a response to a Partisan Review symposium, which served Sontag as a chance to issue a wholehearted attack on America, using a kind of irresponsible rhetoric that would become standard-issue on the left in that polarized decade.

Most famously, she declared that “the white race is the cancer of human history; it is the white race and it alone—its ideologies and inventions—which eradicates autonomous civilizations wherever it spreads, which has upset the ecological balance of the planet, which now threatens the very existence of life itself.” Sontag praised the lifestyle experiments she would go on to condemn in “Fascinating Fascism,” sympathizing with “the gifted, visionary minority among the young” and “the complex desires of the best of them: to engage and to ‘drop out’: to be beautiful to look at and touch as well as to be good; to be loving and quiet as well as militant and effective—these desires make sense in our present situation.”

Yet even in Styles of Radical Will, Sontag is clearly wrestling with her own scruples about the limits of the “new sensibility.” This is especially clear in one of the book’s best essays, “The Pornographic Imagination.” In keeping with the program of Against Interpretation, Sontag sets out to argue that pornography should not be too quickly written off as a vulgar or utilitarian genre. The Marquis de Sade and The Story of O, she writes, have their own wisdom; they are experiments in spiritual extremity and have something in common with the ordeals of religion. “The exemplary modern artist,” she writes with aphoristic flair, “is a broker in madness.”

Yet by the end of the essay, she cannot avoid the question of whether the authenticity and spiritual integrity of pornography make it proper reading, or viewing, for the average sensual man, who is not inclined to put it to such elevated or intellectual purposes. Sontag remains evasive, not yet ready to state forthrightly what she will say in “Fascinating Fascism,” but already she recognizes what is at issue: “The question is not whether consciousness or whether knowledge, but the quality of the consciousness and of the knowledge. And that invites consideration of the quality or fineness of the human subject—the most problematic standard of all.”

Sontag writes so exigently and intelligently about pornography that it is easy to miss the basic comedy of “The Pornographic Imagination,” which is the basic paradox of all her most radical and groundbreaking work. After all, this is a writer who praises the liberating power of porn by turning it into a spiritual and intellectual experiment—that is, by draining it of any sensuality, any genuine transgressiveness. “However fierce may be the outrages the artist perpetrates upon his audience, his credentials and spiritual authority ultimately depend on the audience’s sense … of the outrages he commits upon himself,” Sontag writes, thus shifting the grounds of discussion from pleasure to “spiritual authority” and—an even less erotically charged term—“credentials.”

Credentials, in fact, are an important category of Sontag’s thought. The ones that matter to her are not university degrees or professorships—after starting out in academia, she spent her whole career defiantly outside the academic system—but something more profound, if still capable of misuse: seriousness. Indeed, you could learn a lot about Sontag just by following the career of the word “serious” in her work. In “The Aesthetics of Silence,” she notes that a writer who stops writing, such as Rimbaud, thereby earns “a certificate of unchallengeable seriousness”; silence is what happens “whenever thought reaches a certain high, excruciating order of complexity and spiritual seriousness.” In her essay on Elias Canetti, “Mind as Passion,” she praises the way “his work eloquently defends tension, exertion, moral and amoral seriousness.” In the introduction to Reborn, the first volume of Sontag’s diaries, her son David Rieff recounts the story of how her Oxford tutor, the philosopher Stuart Hampshire, once sighed to Sontag: “Oh, you Americans! You’re so serious … just like the Germans.” “He did not mean it as a compliment,” Rieff observes, “but my mother wore it as a badge of honor.”

What makes Against Interpretation Sontag’s most important and powerful book is precisely its unconscious, unresolved ambivalence about seriousness. Ozick, taking Sontag’s words at face value, saw her as launching an assault on seriousness. But if you pay as much attention to the form as to the substance of the book, it is unmistakable that this attack on seriousness was made with every trapping and intention of seriousness. A person who genuinely believes in the senses over the intellect, in erotics over hermeneutics, does not write long, erudite essays in praise of the senses and publish them in Partisan Review. Against Interpretation talks about vices in terms that make them virtues, just as Sontag would later do with pornography.

So great is the disconnect in Against Interpretation between what Sontag is saying and the way she is saying it, and the people she is saying it to, that this disconnect itself represents its lasting source of interest. The ideas and attitudes Sontag advances in her early work now seem utterly period—they couldn’t even keep her interest for long—and the same is true of many of the works she writes about: No one today could feel as reverent toward Godard and Antonioni as Sontag was in 1966. What matters about Sontag now—and this is an evolution typical of many or most critics—is not what she said, but why she said it; not the work, but the person who produced it, and for whom it served certain psychic purposes. Page by page, Sontag’s work has mostly lost its power to thrill. What survives, as Ozick and Paglia intuited, is her image, and the tortuous connections between that image and the woman who projected it.

***

For that story, the key texts are Sontag’s journals, which contain a human drama more fascinating than anything in her essays or her fiction. The first act of that drama was told in Reborn, the first published volume of the journals, which covered the years 1947 to 1962. Now the publication of the second volume, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1963-1980, takes us through the years of Sontag’s greatest celebrity and accomplishment. When the book opens, she is 31 years old and the author of a single, not particularly well-received novel, The Benefactor. By the time it closes, she has published Against Interpretation, Styles of Radical Will, On Photography, Illness as Metaphor, and other books; directed several films; and become famous on two continents. Here is how Sontag sums up her career standing in 1978:

In every era, there are three teams of writers. The first team: those who have become known, gain “stature,” become reference points for their contemporaries writing in the same language. (e.g. Emil Staiger, Edmund Wilson, V.S. Pritchett). The second team: international—those who become reference points for their contemporaries throughout Europe, the Americas, Japan, etc. (e.g. Benjamin). The third team: those who become reference points for successive generations in many languages (e.g. Kafka). I’m already on the first team, on the verge of being admitted to the second—want only to play on the third.

This entry is noteworthy not only for the guilelessness of its ambition—there is something very American about the notion of literature as a series of farm teams, leading up to the major leagues—but because it is one of the few occasions in the journals where Sontag thinks in such self-conscious terms about her “standing.” For the truth is that Sontag spends very little time, in the diaries as edited by David Rieff at any rate, worrying about her career, or about what the public thinks of her. She is far too intent on her own inner experience, on the creation of her self, to care about her image—something that might have surprised Paglia or Ozick, for whom that image seemed so carefully cultivated. And the utter sincerity of the diaries, the sense that Sontag is always able to speak honestly to and about herself, is what makes them such compelling documents. The contrast with the recently published diaries of Alfred Kazin is striking: Where Kazin is always exhorting and dramatizing himself, Sontag seems genuinely to explore and challenge herself.

The first volume of Sontag’s diaries is more dramatic than the second, because they cover a more dramatic and formative period in her life. Reborn tells the story of a brilliant, enormously ambitious and self-conscious adolescent, who at the age of 15 sets down a hundred-item reading list for herself, and collects obscure vocabulary words (“effete, noctambulous, perfervid”), and vows to live on a large scale: “I intend to do everything … to have one way of evaluating experience—does it cause me pleasure or pain, and I shall be very cautious about rejecting the painful—I shall anticipate pleasure everywhere and find it, too, for it is everywhere!”

The first act of Reborn shows Sontag just about to find herself, thanks to the independence she enjoyed at Berkeley, where she started college, and above all to the lesbian community she experienced for the first time there and in San Francisco. For while she was always hesitant to make it part of her public identity as a writer, the diaries show that Sontag knew she was a lesbian from earliest adolescence, if not before. An important part of the “everything” she wanted to do was sexual, and you can feel the excitement and release in her descriptions of her first sexual encounters: “I have always been full of lust—as I am now—but I have always been placing conceptual obstacles in my own path.”

Then all at once, and with not a word of explanation in the journals, Sontag swerves off this path and gets married, at the age of just 17, to Philip Rieff, her teacher at the University of Chicago, where she transferred for her sophomore year. The ensuing years-long gap in the diaries is a dire signal, suggesting that marriage switched off Sontag’s inner life entirely. When the journals resume, it is with a desperate cynicism about marriage that speaks volumes: “Whoever invented marriage was an ingenious tormentor. It is an institution committed to the dulling of the feelings. The whole point of marriage is repetition,” Sontag writes in 1956. Even worse, she imagines showing her journals one day to her great-grandchildren: “To be presented to my great grandchildren, on my golden wedding anniversary. ‘Great Grandma, you had feelings?’ ‘Yeh. It was a disease I acquired in adolescence. But I got over it.’ ”

There is nothing in the journals (as published) about the details of Sontag’s marriage to Philip Rieff, but details are hardly necessary. Without Sontag casting aspersions on Rieff’s character, the reader can tell that she has made a horrible mistake, that she should never have entered into this marriage; and the journals only resume when Sontag starts to admit this to herself. This is a sign of how keeping a diary, for Sontag, was not a matter of recording the details of everyday life. The reader of her journals never learns, for example, just how she managed to make a living writing long essays on Barthes and Artaud. Rather, as she writes, “in this journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself. The journal is a vehicle for my sense of selfhood. It represents me as emotionally and spiritually independent. Therefore (alas) it does not simply record my actual, daily life but rather—in many cases—offers an alternative to it.”

The title Reborn was aptly chosen for the first volume of diaries by David Rieff—the son of Sontag and Philip Rieff, whose feelings about editing and publishing his mother’s intimate confessions can only be imagined. For starting in the late 1950s, when Sontag left husband and son in the United States while she went to study at Oxford, she deliberately and ruthlessly gave herself a new birth—essentially, by resuming the life she had glimpsed as a teenager and then given up. We follow Sontag in France, having love affairs with women, reading and thinking and beginning to write, with some of the sense of guilty liberation that she herself must have experienced. This was emphatically a woman’s liberation, and Reborn deserves to become a classic feminist document, for the way it shows Sontag painfully unlearning the stereotypical role of wife and helpmeet. “I’m not a good person. Say this 20 times a day. I’m not a good person. Sorry, that’s the way it is,” she adjures herself in 1961.

For Sontag, duty and desire clashed in an especially intricate fashion, as she shows in a diary entry from 1960: “The will. My hypostasizing the will as a separate faculty cuts into my commitment to the truth. To the extent to which I respect my will (when my will and my understanding conflict) I deny my mind. And they have so often been in conflict. This is the basic posture of my life, my fundamental Kantianism.” There is a paradox in the way Sontag uses Kant’s ideas and vocabulary. According to Kant, reason instructs us about what is good, and the will must be disciplined to carry out the edicts of reason. What Sontag means, however, is just the reverse: For her, the will to do “good”—to be a good wife and mother, by sacrificing her own ambitions—was what had to be resisted. It was her reason that instructed her to do “wrong,” by abandoning her marriage to follow her own path.

The sense that she had to reason herself into defying her own “will” is absolutely central to Sontag’s early work, especially Against Interpretation. Read in the light of the diaries, it becomes clear why Sontag argued in such intellectualized and dutiful terms against the intellect and duty. She commands the world to an “erotics of art” just as she commanded herself to be faithful to her own erotic nature; she apotheosizes experience at a time when she was in search of all the experiences she had missed. But she does all this in terms that make eroticism a discipline and experience an obligation, in language as rigorously argumentative as she could make it. As she puts it in 1965, in As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh, she was “becoming inhuman (committing the inhuman act) in order to become humane.” Following the will could only become acceptable to Sontag if the will were commanded by reason, just as Kant had it: She was a hedonist according to the categorical imperative.

Which is really to say that she was not much of a hedonist. “Not to give up on the new sensibility (Nietzsche, Wittgenstein; Cage; McLuhan) though the old one lies waiting, at hand, like the clothes in my closet each morning when I get up,” she warns herself. One of the rare comic moments in As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh comes when Sontag is in Tangiers, hanging out with Paul Bowles, and has a revelation about the counterculture. To her, the counterculture was a grand intellectual and aesthetic experiment, a matter of “new sensory mixes.” But she now realizes that a large part of what struck her as its strangeness is owed simply to the fact that its adherents were stoned all the time:

This is what the beat generation is about—from Kerouac to the Living Theatre: all the “attitudes” are easy—they’re not gestures of revolt—but natural products of the drugged state-of-mind. But anyone who is with them (or reads them) who isn’t stoned naturally interprets them as people with the same mind you have—only insisting on different things. You don’t realize they’re somewhere else.

One can imagine Sontag getting stoned only in the same spirit that Walter Benjamin tried drugs, in order to experiment with consciousness. Similarly, it becomes clear in the journals that Sontag supported the sexual revolution not because she was at ease with eroticism, but precisely because she was not. “I am so very much more cool, loose, adventurous in work than in love,” she admits to herself. Much of the second volume of her journals is given over to agonized reflections on failed love affairs, in which she reproaches herself mockingly for her sexual incompetence: “Why can’t (don’t) I say: I’m going to be a sexual champion? Ha!” Similarly, the Sontag who clued in the Partisan Review readership to the excitement of “happenings” can be found writing: “I feel inauthentic at a party: Protestant-Jewish demand for unremitting ‘seriousness.’ ”

It was not easy to be so serious. Sontag writes movingly and very candidly about the way her great intelligence made life and relationships difficult for her, starting from early childhood: “Always (?) this feeling of being ‘too much’ for them—a creature from another planet—so I would try to scale myself down to their size, so that I could be apprehendable by (lovable by) them.” Many entries, clearly inspired by sessions with a therapist, show Sontag tunneling down to her early childhood, trying to understand how her father’s early death and her difficult relationship with her mother have conditioned her adult life.

But for Sontag, intelligence and seriousness were far too integral to her sense of self to be wished away. She is always prepared to double down on seriousness: “Seriousness is really a virtue for me, one of the few which (I) accept existentially and will emotionally. I love being gay and forgetful, but this only has meaning against the background imperative of seriousness,” she writes in 1958, in Reborn.

And in the second volume of journals, she circles around, but never quite reaches, a revelation about “seriousness” that explains many of the flaws of her criticism. Though Sontag announced at the age of 5 that she was going to win the Nobel Prize, by the 1960s she was worrying, “My mind isn’t good enough, isn’t really first rate. … I’m not mad enough, not obsessed enough.” (Ironically, Sontag in this vein sounds exactly like Lionel Trilling in his journals—although conscientious old Trilling was Sontag’s foil in Against Interpretation.) But it was not insufficient madness or obsession that limited Sontag’s work as a critic.

Rather, it is precisely her reverent—or, more precisely, her acquisitive—attitude toward seriousness that makes her essays so solemnly, ostentatiously intelligent. “I make an ‘idol’ of virtue, goodness, sanctity. I corrupt what goodness I have by lusting after it,” she writes in 1970. The same could be said of her worship of seriousness: A person who is instinctively sure that she is serious does not spend so much time proving it. Irony and wit, qualities signally absent from Sontag’s work, are only possible when seriousness is the premise of one’s self-conception, rather than the result that must be achieved.

This explains why so much of what has been written about Sontag after her death paints her as a rather ludicrous figure. In Terry Castle’s barbed elegy “Desperately Seeking Susan,” or in Sigrid Nunez’s short book Sempre Susan, Sontag often comes across as hugely self-centered and inadvertently comic—and the best way to be inadvertently comic is to always insist on being, and looking, serious. If Sontag’s inner life, as revealed in the diaries, is a moving drama, to other people she evidently seemed more like Dr. Johnson—a figure of massive egotism and unconscious eccentricity. It’s too bad that she had no Boswell following her around day after day to put her fully on paper; but even if she had, an outsider could have known only part of the truth about her. The more important parts are to be found in her essays, her novels, and—above all—in her diaries.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.