The Great Swamp Monster Confluence of 1971

Tracing the tangled, Jewish origins of three iconic comic book characters

Shlaap. Schglorp. Ploog-plossh. Guush. Schglorp ...

Heavy footsteps. Coming up behind you. Heavy footsteps sinking in the grasping mud, through the soft, wet soil of the swamp. Don’t turn around. You don’t want to see it. Just keep moving. But it’s coming up behind you ...

Such was the clammy terror faced by readers of horror comics in 1971. Within the space of just a few months, the miasma-infested wetlands of their imaginations were invaded by not one, or two, but three different swamp monsters, each set loose on the reading public by a different comics publisher. And just as you can’t tell where one set of roots and vines ends and another begins, such was the case with the origins of the three muck creatures. Their beginnings were all tangled together, imaginative offshoots of the often incestuous dealings within the tightly knit, still relatively small comic book community of the early 1970s.

Perhaps this was because each one of them had at least one creator (a writer, artist, or editor) who, like Chief Rabbi Yehudah Loew of Prague, creator of the first mud monster, the Golem, was Jewish.

Of the horror archetypes of Western popular culture—the vampire, the werewolf, the witch or warlock, the demon, the revenant, the spree killer, the zombie (original Haitian flavor or extra-spicy Romero version)—two can be said to have roots in the Jewish legend of the Golem of Prague: the Frankenstein monster and the swamp monster.

Just as the Golem of Prague was created from elements of the earth, from mud excavated from the Moldova River, so too did Dr. Frankenstein create his creature from elements that would soon otherwise merge with the earth— portions of buried corpses.

The Golem had no will of its own, existing only to follow its rabbi’s commands, but it was considered a benevolent and spiritually pure creature. Nearly all the most prominent swamp monsters share the Golem’s quality of essential benevolence; they are misunderstood antiheroes who incite horror yet ceaselessly strive to regain their lost humanity. They often aid deserving and downtrodden persons they come across, saving them from the depredations of evildoers. Some share the Golem’s mindlessness and benevolent essence. Others retain their human intellects and personalities and are driven by their consciences to aid whichever unfortunates they come across.

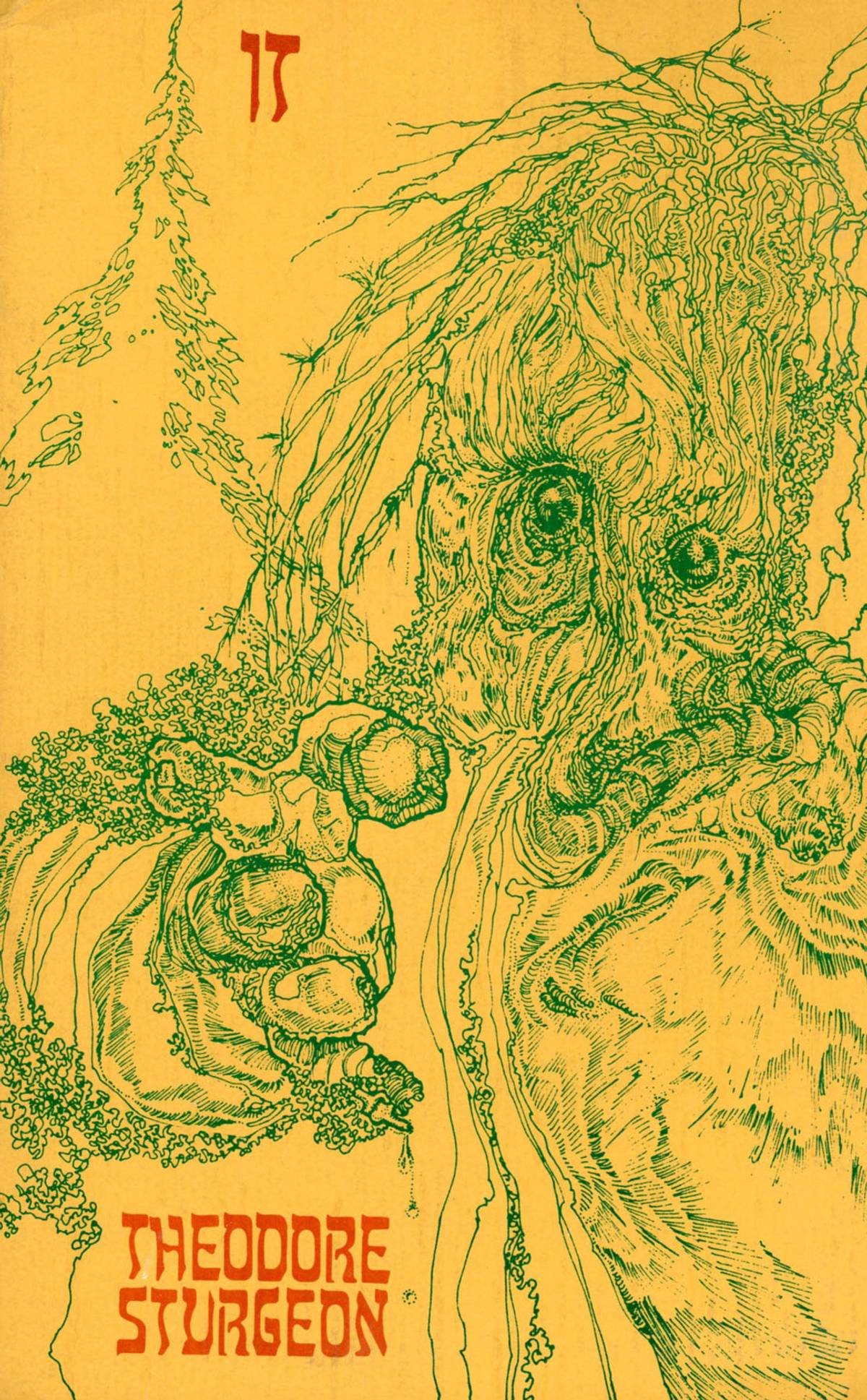

Unlike the other horror archetypes mentioned earlier, who have become imprinted on the nightmares of Western audiences mainly through books, films, or television programs, swamp monsters have invaded our imaginations primarily through the media of pulp fiction magazines and their closely related cousins, comic books. The grand-daddies of all subsequent swamp monsters appeared in the August 1940 issue of the fantasy pulp Unknown—Theodore Sturgeon’s “It”—and the December 1942 issue of air war comic book Air Fighter Comics—Mort Leav’s and Harry Stein’s the Heap.

Theodore Sturgeon was, along with his contemporary, Ray Bradbury, among the first notable prose stylists in the genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. In “It,” Sturgeon conjured a creature made of subterranean molds that, when heated by underground fires, congealed around the skeleton of a dead man and rose to terrorize and stalk a farm family. Interestingly, Sturgeon chose not to portray this creature as evil, but rather amoral and emotionless, driven to acts of hateless destruction by curiosity. The author placed his readers in the mind of the creature as, seeking to understand its surroundings, it conducts simple experiments on the animals and people it comes across, not realizing its efforts result in their deaths.

Sturgeon described his creature this way:

It was never born. It existed ... It was huge. It was lumped and crusted with its own hateful substances, and pieces of it dropped off as it went its way ... It had no mercy, no laughter, no beauty. It had great strength and great intelligence ... And whose dead bones had given it the form of a man?

The story ends (skip this paragraph if you intend to read “It” for the first time) with perhaps the most surprising yet logical denouement for a monster in the annals of horror literature. The creature’s curiosity about flowing water results in its destruction when it accidentally falls into a swift-moving stream. Rather than attempt to right itself and escape, the creature observes its shrinkage with great interest, until so much of it has washed away that it is unable to observe anymore, leaving only the bare bones of a long missing man behind.

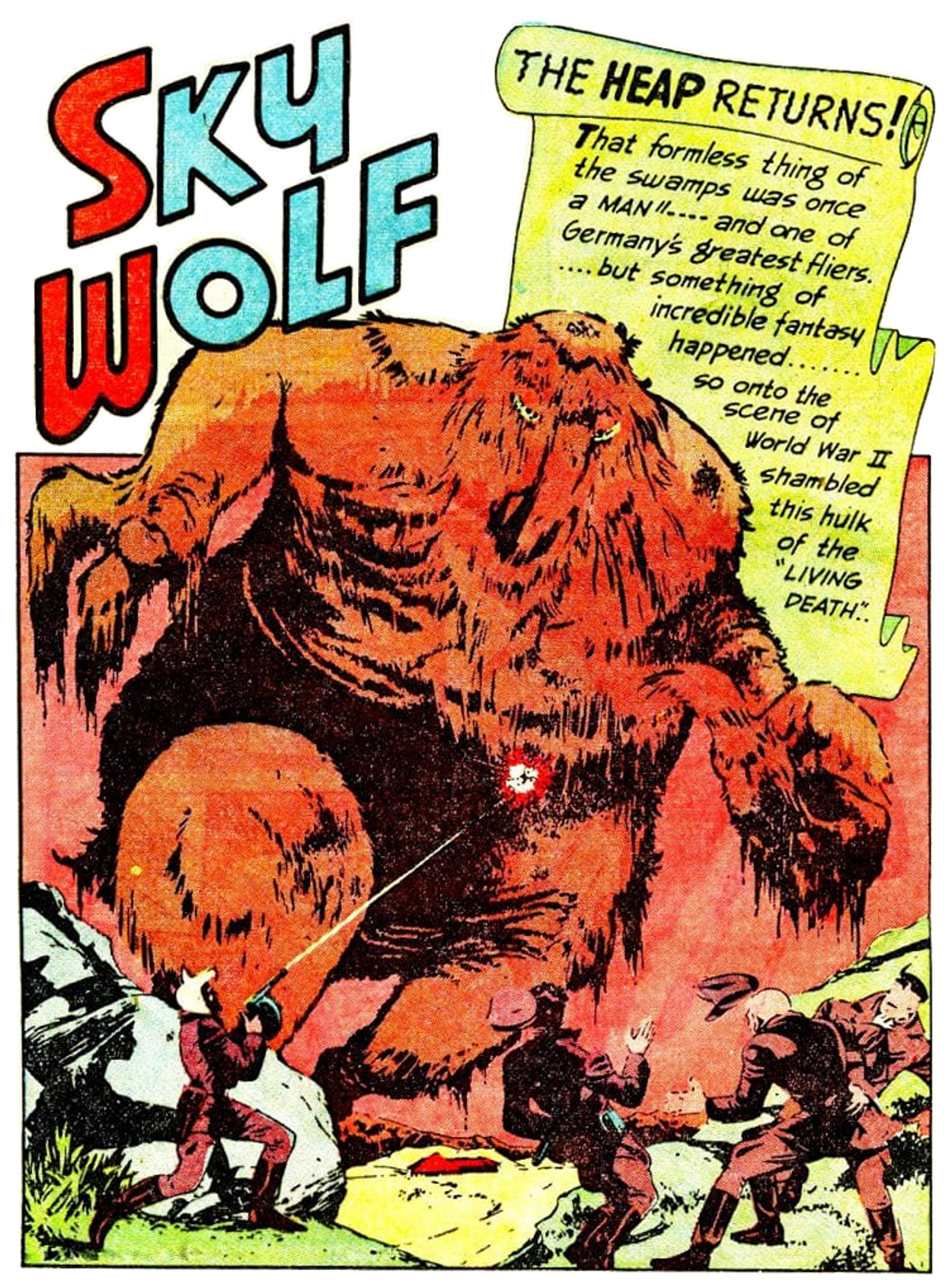

Two years prior to the publication of “It,” former book publisher Alex Hillman jumped into the booming field of comic books. After his first three attempts at putting out a successful comic book failed, Hillman discovered a winning formula with Air Fighters Comics in November 1941. One of the star features of Air Fighters Comics was Sky Wolf, a mercenary pilot who wears a wolf’s head hood over his flying suit and leads a squadron of international flying mercenaries against the Nazis.

A series starring a World War II flying ace and his pals might seem an unlikely venue for the debut of the second of our seminal swamp monsters, but early comic books were often charmingly eclectic that way. A pair of Jewish creators, writer Harry Stein (actual name Harry Smilkstein) and artist Mort Leav, decided it would be a grand idea to have their new character, the Heap, guest star as a villain in the second Sky Wolf story.

Harry Smilkstein/Stein (1911-1994), born in Stamford, Connecticut, to immigrant parents from Latvia and Russia, began his career in commercial art in 1937. He sold pen-and-ink interior illustrations to pulp magazines, but the burgeoning field of comic books offered many opportunities for an enterprising young artist willing to work hard and fast. So in 1939, Harry switched to working for Jerry Iger’s comics studio. Harry met fellow artist Mort Leav at the Iger shop.

Mort Leav (1916-2005), five years younger than Harry, spent much of his teen years admiring the work of classic illustrators such as Milt Caniff, studying works at New York’s art museums, and painting and drawing animals at the zoo. In 1940, he was hired at the Iger Studio, where he and Harry Smilkstein co-created the star character Sky Wolf for Hillman Publications. In their initial story, they introduced Sky Wolf’s primary nemesis, the Nazi pilot Von Tundra. For Sky Wolf’s second appearance, they wanted to top themselves. They came up with the notion of a creature made of vegetation that would menace Sky Wolf and Von Tundra.

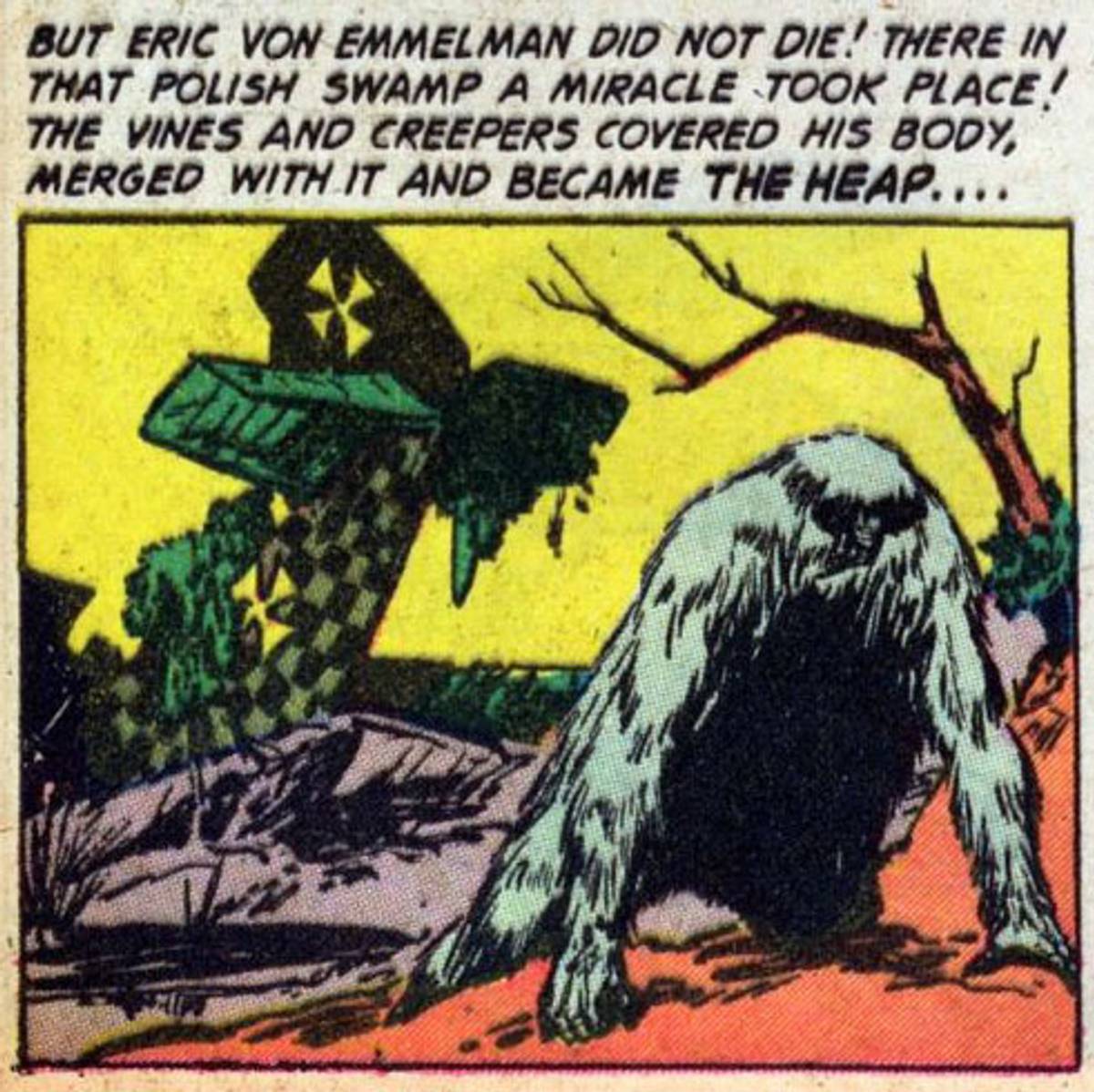

In an interview with longtime comics professional and fan Roy Thomas (of whom more will be said), Mort, when asked if the Heap had been inspired by Theodore Sturgeon’s “It” from two years previous, said he had never heard of Sturgeon. No such interview question was ever posed to Harry Smilkstein, so we’ll never know if he had read “It” before the brainstorming session at the Iger studio that resulted in the Heap. They managed to tie their new swamp monster into the ethos of Air Fighters Comics (later to be retitled Airboy Comics) by having the Heap begin its life as a World War I German flying ace named Baron Von Emmelman. Von Emmelman is shot down in a dogfight over a Polish swamp. His plane crashes in the muck and his badly injured body is thrown clear. However, so strong is his will to survive that he lingers on in the swamp long enough for its vegetation to merge with his body and revive him.

As the Heap, Von Emmelman retains only figments of his memories and ability to think. He is a shaggy Yeti-like creature, roughly man-shaped but nearly as broad as he is tall, and strong enough to lift an automobile. He initially has visible eyes and a mouth with large fangs, but eventually his artists will draw him with those features mostly covered by his hairlike vegetation, and his nose will in turn grow into a prominent, carrotlike appendage. Other aspects of the Heap’s appearance would also change; he starts out white, then becomes brown, then white again, and back to brown. Finally he is colored a sort of pea soup green. His size also changes from story to story, being drawn anywhere from the height of an ordinary man to 8 feet tall. This variability was undoubtedly due to the rapid turnover in the feature’s artists, with both the draft and munitions industries pulling young men away from the comics industry. Harry and Mort only collaborated on the initial appearance of their character, and the Heap’s feature would only attain artistic stability come the late 1940s.

Writers and artists fiddled constantly with the Heap’s origin above and within the dismal Polish swamp. At one point, Von Emmelman’s transformation into the Heap is shown to be guided by Roman deity Ceres, goddess of grain, who uses the Heap as a vegetative champion to foil the schemes of Mars, god of war, who ceaselessly tries to foment conflict among men. In a later story, the Heap’s creator is switched to Mother Nature, and the Heap is granted the ability to control other forms of vegetation (similar to abilities that would later be mastered by DC’s Swamp Thing). Initially, Von Emmelman’s defeat by the enemy pilot is portrayed as a chance occurrence. In a later retcon, his downing is shown to be the result of treachery—a fellow German pilot sabotages the guns of Von Emmelman’s plane.

Taken as a whole, the Heap’s stories are oddball, highly imaginative, and weirdly charming. Near the end of his run, the Heap was mostly facing off against supernatural antagonists, including a giant prehistoric lizard, a man transformed into a walking hunk of lava, a witch, and a voracious, fast-growing, man-eating vine. Comics professionals like Stan Lee and Sol Brodsky who were in the early years of their careers during Airboy’s run fondly remembered the Heap in decades to come, as did fans like Roy Thomas who purchased the Heap’s adventures as a young reader. And therein hinges the strange saga of the Great Swamp Monster Confluence of 1971.

Some sort of murky miasma must have polluted the air of Manhattan during the end of 1970 and beginning of 1971. Images of swamp creatures were infesting everyone’s thoughts, it seemed.

Sol Brodsky (1923-1984) was among those so afflicted. Born and raised in Brooklyn, a dozen years younger than Harry Smilkstein and seven years younger than Mort Leav, he entered the booming comic book industry not long after they did; his earliest job with a comic book company was sweeping floors at the office of MLJ Magazine, publishers of Archie Comics. The early 1960s found Sol doing freelance artwork for editor Stan Lee at Marvel Comics, where he provided art for several early issues of The Fantastic Four. In 1964 he became Marvel’s production manager, Stan’s “right-hand man.” The following year, Sol met young Roy Thomas. Roy, then 24, had been a vital part of early comic book fandom and had only a week before started a position under Mort Weisinger, senior editor at DC Comics. However, Roy felt uncomfortable working under Weisinger and wrote a letter to Stan Lee, who offered Roy a Marvel writing test, which resulted in Stan hiring Roy as his editorial assistant.

Sol and Roy became good friends, joining each other for daily lunches at a diner near the Marvel office. Other members of the Marvel bullpen joined in, and the lunches came to encompass poker games played for nickel stakes. The poker games soon shifted to monthly affairs at Roy’s Manhattan apartment.

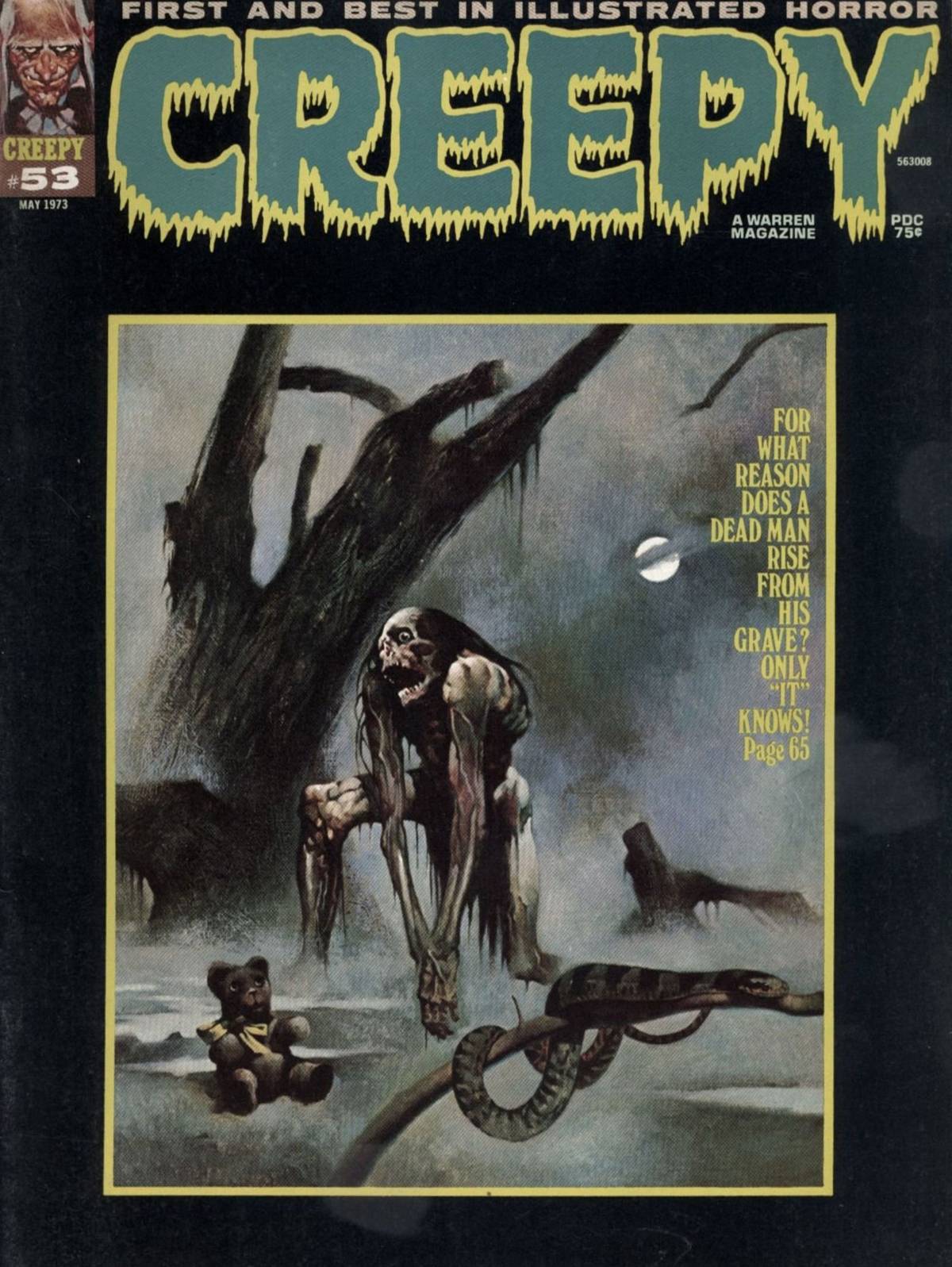

In 1970, Sol revisited his earlier ambition to start his own comic book company. He teamed with comics entrepreneur Israel Waldman to form Skywald Publications (its name combining the last part of Sol’s surname with the first part of Israel’s). James Warren had met with great success with the black-and-white horror magazines Creepy (started in 1964), Eerie (followed in 1966), and Vampirella (rounded out the Warren lineup in 1969). The three magazines initially employed many of the EC Comics artists and writers who had been driven from the horror comics business by the establishment of the Comics Code Authority in 1954, in response to the threat of government censorship of reading materials aimed at kids. Putting out black-and-white magazines allowed Warren to avoid the Comics Code Authority’s prohibition on horror, since its oversight did not extend to magazines. Sol and Israel decided to compete with Warren magazines by publishing their own trio of black-and-white horror magazines, starting with Nightmare (beginning December 1970) and followed shortly thereafter by Psycho (beginning January 1971) and Scream (beginning August 1973).

Roy retained his close friendship with Sol, despite the fact that Sol had started a business in direct competition with his former and Roy’s current employer. They continued meeting for lunches. Roy has recounted that Sol often picked his brain for ideas for new stories and that Roy was the one who suggested to Sol that Skywald resurrect the Hillman Periodicals horror hero the Heap. Roy, ever the comics fanboy, had a warm spot in his memory for the Heap, and he felt that not only would the character be a perfect fit for one of Skywald’s new horror magazines, but the character deserved to be rescued from obscurity.

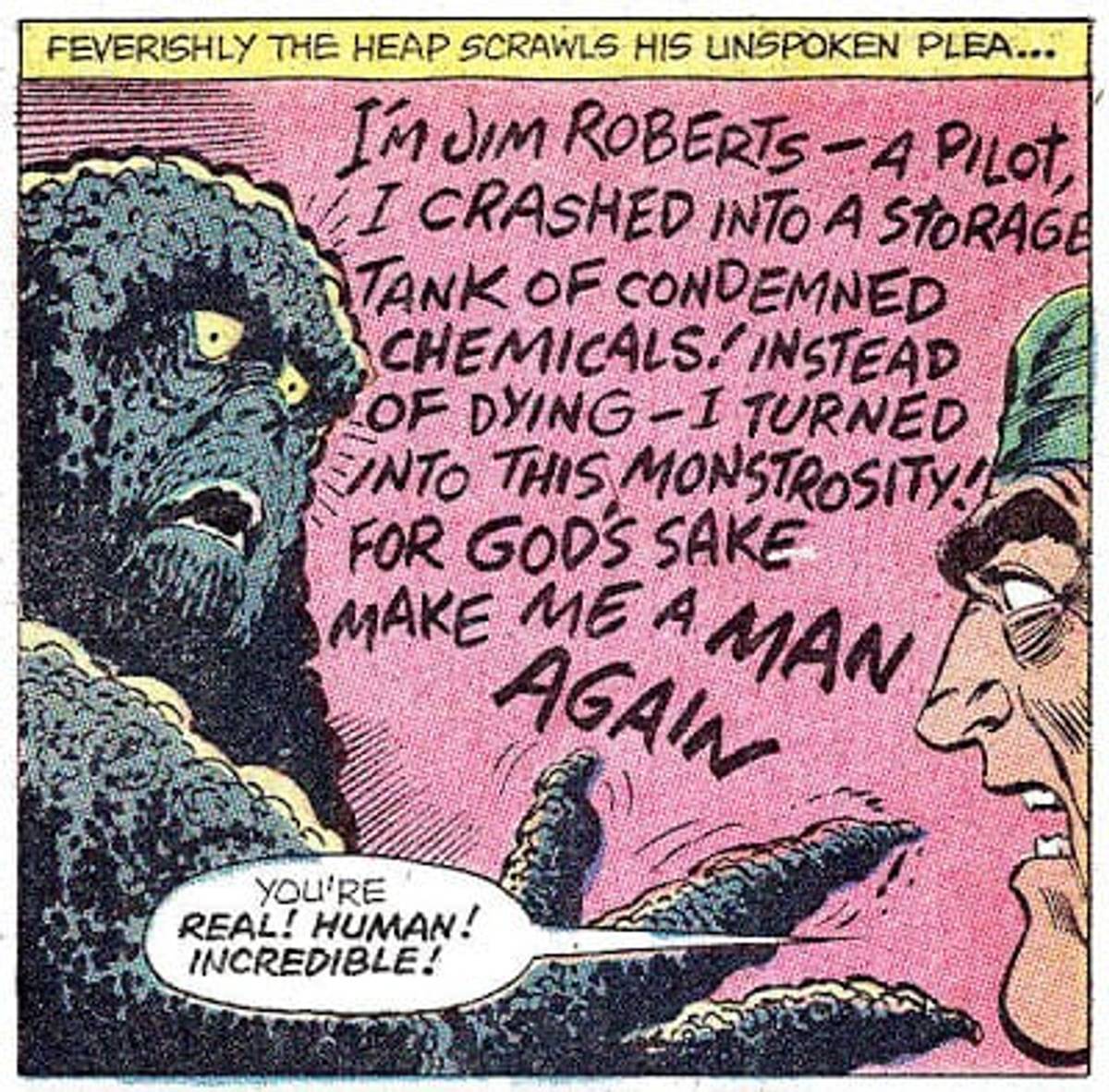

The new Heap had similarities to the original but was a brand-new character whose stories were set in the 1970s. Rather than a World War I flying ace, the new Heap’s human half, Jim Roberts, is a handsome young crop-duster pilot. Betrayed by his fiancee, Audrey, who, intending to collect on a life insurance policy Jim took out with her as beneficiary and also take over Jim’s crop-dusting business, arranges for confederates to sabotage Jim’s biplane, Jim crashes his plane, loaded with pesticides, into the storage tanks of a U.S. Army nerve gas test facility. The volatile chemicals explode, causing a raging blaze that boils the soil beneath the storage tanks. When the fires finally die down, Jim emerges. Not as his former self—the combination of searing heat and his body’s immersion in soil saturated with a mixture of pesticides and liquified nerve gas has transformed him into a speechless lump of a creature, 7 feet tall, nearly as wide as he is tall (roughly the same shape as the original Heap), seemingly composed of dirt and garbage, with a lumpy, oozing hide. Unlike the original, the new Heap retains his full human intellect and all his memories, although he must constantly struggle to subdue savage instincts that threaten to take control of his monstrous form. This Heap spends most of his adventures seeking a cure for his unfortunate condition and battling fellow monsters on the journey, a story arc that would be closely mirrored during the early run of DC’s Swamp Thing a few years later.

The new Heap’s stories generated much enthusiastic fan mail. Unfortunately for Sol and the fledgling Skywald Publications, Marvel, one of the two 500-pound gorillas of the 1970s comic book industry, decided to get in on the black-and-white horror bonanza. Marvel launched a subsidiary imprint, Curtis Magazines, which flooded the newsstands with 30 titles between 1971 and 1975. Nine were horror magazines, with the remainder divided between sword-and-sorcery (Conan the Barbarian and his ilk), humor, martial arts heroes, and film tie-ins. Within just a few years, Marvel’s distributor would muscle the much smaller Skywald line off the majority of the nation’s newsstands. Early on, however, Marvel’s push into this new market was tentative, due to publisher Martin Goodman’s reluctance to do an end run around the Comics Code Authority. Marvel’s line of magazines got off to an abortive start with the publication of the first issue of Savage Tales in May 1971, which would be the title’s only issue until it was revived nearly two and a half years later, following Goodman’s departure from the company. That lonely first issue of Savage Tales in 1971 is notable, however, for featuring the very first appearance of Marvel’s premier swamp monster, the Man-Thing.

As generated by the fecund imagination of Stan Lee (1922-2018), the Man-Thing was initially nothing more than an evocative name and a vague notion of a scientist attacked by spies who ends up transformed into a swamp monster. Stan, who during the first half-decade or so of Marvel’s superhero resurgence had scripted and edited virtually the company’s entire line of comics, had by 1970 segued into a more executive editorial role. Still very much a nonstop ideas factory, he continued supplying character concepts and plots to Marvel’s expanded retinue of writers and artists, who were expected to layer flesh onto the bare bones of Stan’s notions. Roy Thomas’ work had expanded to include a great deal of plotting and scripting; he had gained acclaim as the writer for The Avengers, and he had also co-plotted and scripted issues of The Hulk, Marvel’s Jekyll-and-Hyde-like monster-hero.

With the first issue of Savage Tales in the planning stages, Stan instructed Roy to flesh out his Man-Thing idea. Roy worked up a more detailed plot synopsis and handed it over to writer Gerry Conway to script the story. Roy gave art responsibilities to the magnificent illustrator Gray Morrow, whose design of the Man-Thing paid homage to some features of the Hillman Heap—the Man-Thing retains some of the original Heap’s shagginess, and the former shares the latter’s distinctive long, sagging, carrot-shaped nose, this time combined with a similarly shaped brow ridge that extends beyond his temples to droop over his cheeks.

Unlike either of the men who became monsters named the Heap, Ted Sallis, the man destined to become the Man-Thing, was not an airplane pilot. Instead, he is a government chemist who is working on a top-secret project to recreate the super-soldier formula used to empower Captain America in 1940 ... but with the added properties that the resultant super-soldiers be essentially indestructible and (according to a later addition to the lore) able to thrive in highly polluted environments. He performs the final stages of his work in an isolated cabin/laboratory shared with his lover, Ellen Brandt, hidden deep within the Florida Everglades, where he synthesizes a sample dosage of the serum. When his security handler Hamilton fails to show at the scheduled time to collect the sample, Sallis suspects something has gone awry and burns his notes, leaving his memory as the only source of the formula. He and Ellen board an air boat to take the sample to Hamilton at his cabin. At their destination, Sallis discovers Hamilton’s dead body and his killers—a pair of gun-toting spies from AIM (Advanced Ideas Mechanics), a terror organization who want to use the super-soldier formula for their own nefarious purposes. Ellen is revealed as a turncoat who sold her lover out for cash. Sallis breaks away and steals a car. Determined to not allow the sole sample to fall into AIM’s hands, he disposes of it by injecting it into himself. However, the shock of injecting the experimental serum into his bloodstream causes Sallis to lose control of his vehicle and he crashes through a guard rail into a bottomless section of swamp.

Science and magical forces combine to mutate Sallis’ sinking body; as the super-soldier serum transforms him from within, the mystical elements of the swamp transform him from without. He emerges from his watery “grave” as an 8-foot-tall shambling monstrosity capable of lifting 10 tons or more, impervious to bullets or other penetrating weapons (they harmlessly go right through him, since he is now composed of swamp muck), and essentially mindless, driven by an empathic nature and attracted to strong instances of emotion. In this, the Man-Thing strongly resembles the original Heap, but with one key addition—when he takes revenge on the spies who destroyed his life, including Ellen, his touch causes horrible burns, and in his third appearance it is revealed that “whatever knows fear burns at the Man-Thing’s touch!”

So, which came first: Stan’s directive that Roy oversee the creation of a Man-Thing story, or Roy’s suggestion to Sol Brodsky that the latter resurrect the Heap? In one version of his recounted memory, Roy stated he told Sol to hurry a version of the Heap into print as fast as he could, as Marvel was planning to introduce a very similar character, the Man-Thing. Roy’s memory in this instance must be foggy, however, because that chronology of events does not add up. It’s far more probable that Roy’s discussion with Sol came first, followed (coincidentally or not) shortly thereafter by Stan’s directive that Roy come up with an origin story for a swamp monster, part man and part muck, to be called the Man-Thing. It’s fun to speculate on whether Stan had gotten wind of his former employee Sol’s plan to reintroduce the Heap (although Stan’s fixating on the character name “Man-Thing” and draping a rough idea over that suggest a separate genesis) and on the sort of thoughts that must have gone through Roy’s head when Stan gave him his marching orders (oh, boy, I sure hope the boss never finds out who suggested to Sol that he bring back the Heap ...).

The tale of the Great Swamp Monster Confluence of 1971 grows even more tangled when we learn who was assigned the job of writing the Man-Thing’s second story. This was first scheduled for Savage Tales No. 2, which, had things gone according to plan, would have hit newsstands in May 1971, meaning the story would likely have been written and drawn in January or February 1971. This writer happened to be Len Wein (1948-2017). A native of the Bronx and Levittown, New York, Len would later become famous in the world of comics for his invention of the popular Marvel hero Wolverine, his work on creating the All-New, All-Different X-Men for Marvel, for many years that company’s most popular set of characters, and for being the co-creator of none other than ... DC’s Swamp Thing.

A couple of other odd coincidences involving Len Wein have a bearing on our tale of swampy confluence. Since the age of 14, Len had been best friends with Gerry Conway, the Man-Thing’s first scripter. Not only that—the two young comic book writers were roommates during the few months in which both the first Man-Thing story and the first Swamp Thing story were written.

In an introduction he wrote for a collected edition of his earliest Swamp Thing stories, Len, who had begun his comic book writing career as a freelancer for DC Comics in 1968, recalled the genesis of that first Swamp Thing story. The idea came to Len about a week prior to Christmas of 1970 during his half-hour subway ride from his Queens apartment to the Manhattan office of DC Comics. Nothing too ambitious; just a brief story for one of DC’s mystery anthologies, involving a Victorian-era scientist, his best friend, the woman they both love, betrayal, revenge ... and a swamp monster. He made no mention of any late-night bull sessions with his roommate Gerry Conway, who would have been handed his assignment to write the first Man-Thing story right around that time. Len was fortunate in that his editor Joe Orlando happened to be a fan of Theodore Sturgeon’s story “It” and so granted his enthusiastic approval for Len’s story to appear in an upcoming issue of The House of Secrets.

The next weekend Len attended a Christmas party at the Long Island home of his buddy Marv Wolfman, a fellow comics writer, and found himself trying to cheer up a very glum Bernie Wrightson, an outstanding young comics artist who had just broken up with his girlfriend. Len mentioned he had just written a story involving a man-monster’s unbearable heartbreak. He suggested that Bernie illustrate the story as a way of working through his own heartbreak. Bernie agreed.

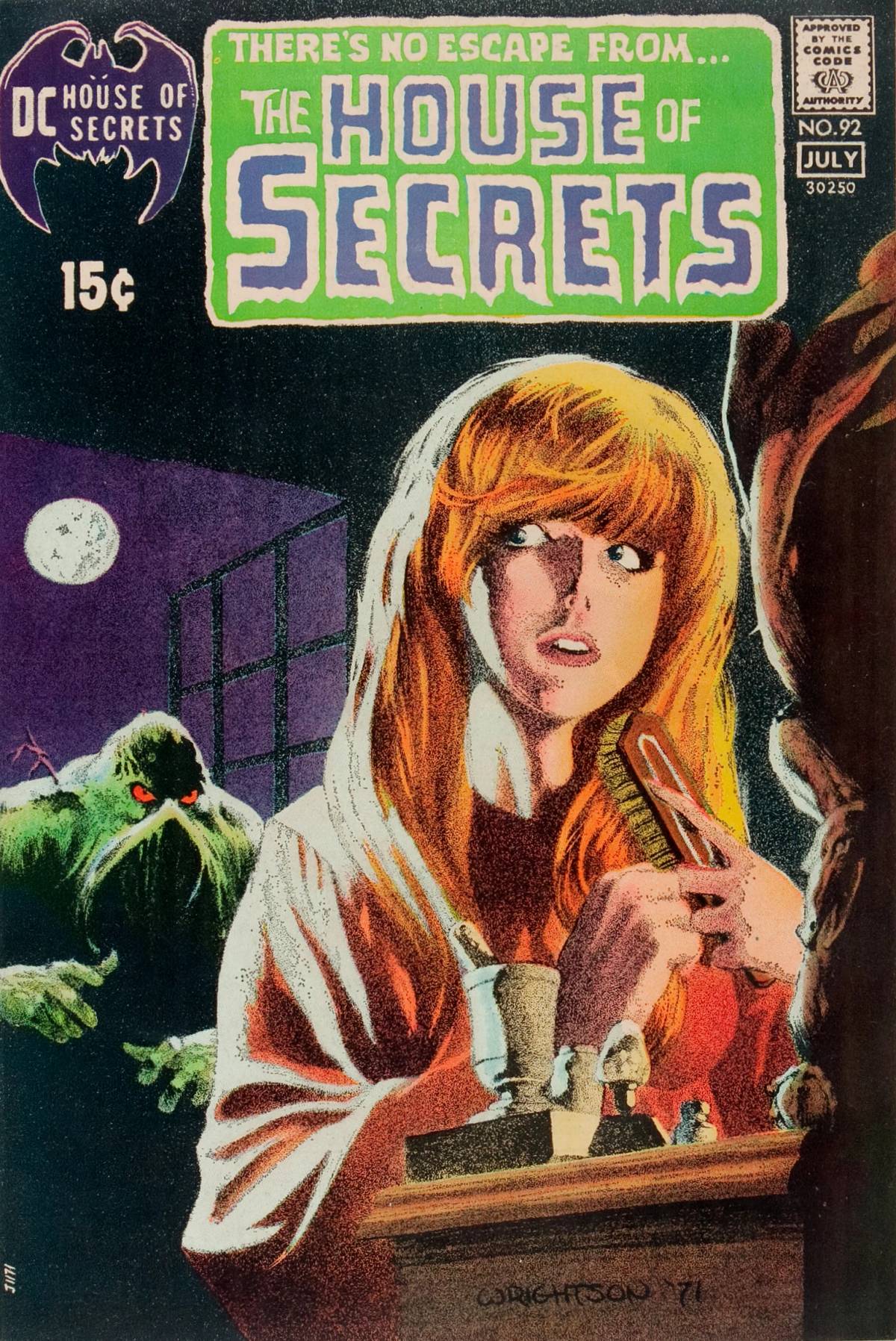

The eight-page short appeared on the newsstands in May 1971 as the cover story for issue No. 92 of The House of Secrets. It features three characters: scientist Alex Olsen, his wife, Linda, and their best friend Damian Ridge, a fellow scientist who is secretly in love with Linda. Desiring her for his own wife, Damian sabotages Alex’s lab with a bomb, then carries the mutilated, seemingly dead body of his former friend to dump it in a neighboring swamp. By now, you can guess much of the rest—Damian cajoles Linda to marry him after a short period of mourning; Linda comes to suspect Damian’s involvement in the death of her former husband; Damian plots to dispose of her before she can reveal his perfidy; Alex emerges from the swamp as a speechless Heap-like monster; the Swamp Thing takes his revenge on Damian while saving Linda’s life, but Linda shrieks in horror at the sight of the creature and poor Alex retreats back to the swamp.

The big surprise for Len and Bernie came a couple of months later, when DC’s sales figures showed that issue of The House of Secrets had been the company’s bestselling title of the month, beating out such sales titans as Batman, Detective Comics, and Superman. Most of the credit for this unexpected leap in sales must be granted to Bernie Wrightson’s striking cover, featuring a very fetching Linda sitting before her bedroom vanity combing her blond hair, not noticing the Swamp Thing looming behind her, about to enter through an open window. DC publisher Carmine Infantino smelled a hit and insisted the Swamp Thing be given his own book and that Len and Bernie write and draw it. However, the two young idealists retorted that the story of Alex Olsen was a one-and-done and that attempting to churn out sequels would take away the story’s emotional impact. For most of the following year, they resisted entreaties to put out a bimonthly Swamp Thing book.

Eventually it must have occurred to them that idealism doesn’t pay rent or purchase Chinese takeout for young comics freelancers. They reconciled themselves to the cold dictates of commerce by telling themselves they could preserve the integrity of their original story by making the series about a different Swamp Thing, Alec Holland. This creature is the most manlike of any of the swamp monsters we’ve met; Alec retains his intelligence and even some ability to haltingly speak.

Swamp Thing No. 1 shambled onto America’s newsstands in August 1972 with an October-November 1972 cover date, a year and a quarter after House of Secrets No. 92. Len and Bernie would team up for a fan-favorite, 10-issue run that featured the Swamp Thing seeking a cure for his affliction while battling a weird rogues gallery of mad scientists and updated versions of the Universal Studios monsters of the 1930s.

Meanwhile, back at Marvel, Stan and company believed in never letting an already-paid-for story go to waste. The Man-Thing was granted his own series, albeit in the tryout comic Adventures into Fear, starting with issue No. 10, cover dated October 1972 (on the newsstands contemporaneously with Swamp Thing No. 1). In Fear No. 10, the Man-Thing was reunited with his original creative team of writer Gerry Conway (Len’s roommate) and artist Gray Morrow. A new writer, Steve Gerber, the one to be most closely identified with the character, took over scripting chores with the following issue and stuck with Man-Thing through the subsequent nine issues of Fear and into the monster’s own title, The Man-Thing, its first issue in January 1974.

The members of the Swamp Monster Class of 1971 achieved subsequent levels of success inverse to the characters’ order of first appearance. Skywald’s the Heap sputtered out the earliest. Marvel’s distribution firm smothered the young company; Sol Brodsky got out in 1973 when his initial investment ran out and returned to Marvel, where he became the production supervisor for Marvel’s new British line, Marvel UK. The Heap’s home magazine, Psycho, lasted until issue No. 24 in March 1975 and was Skywald’s last publication.

Marvel’s Man-Thing fared better. The creature enjoyed a long run that benefited from the imagination of gifted writer Steve Gerber. According to the book Swampmen: Muck-Monsters of the Comics by Jon B. Cooke, Steve and Len worked out an arrangement in the 1970s whereby the Man-Thing and the Swamp Thing, despite their suspiciously similar origin stories, would trod very different narrative arcs. Steve’s Man-Thing stories would center around mystical, epic fantasy adventures emerging from the fact of the creature’s home swamp being the Nexus of All Realities. As the series wound on, Steve wrote more personal and idiosyncratic stories that are fondly remembered by fans of 1970s oddball comics, including acclaimed fantasy author Neil Gaiman. Man-Thing’s popularity has waxed and waned over the decades. Apart from his first series, Man-Thing comics have tended not to have much staying power, but Marvel writers continue to use him as a supporting character in other horror or superhero series and anthologies.

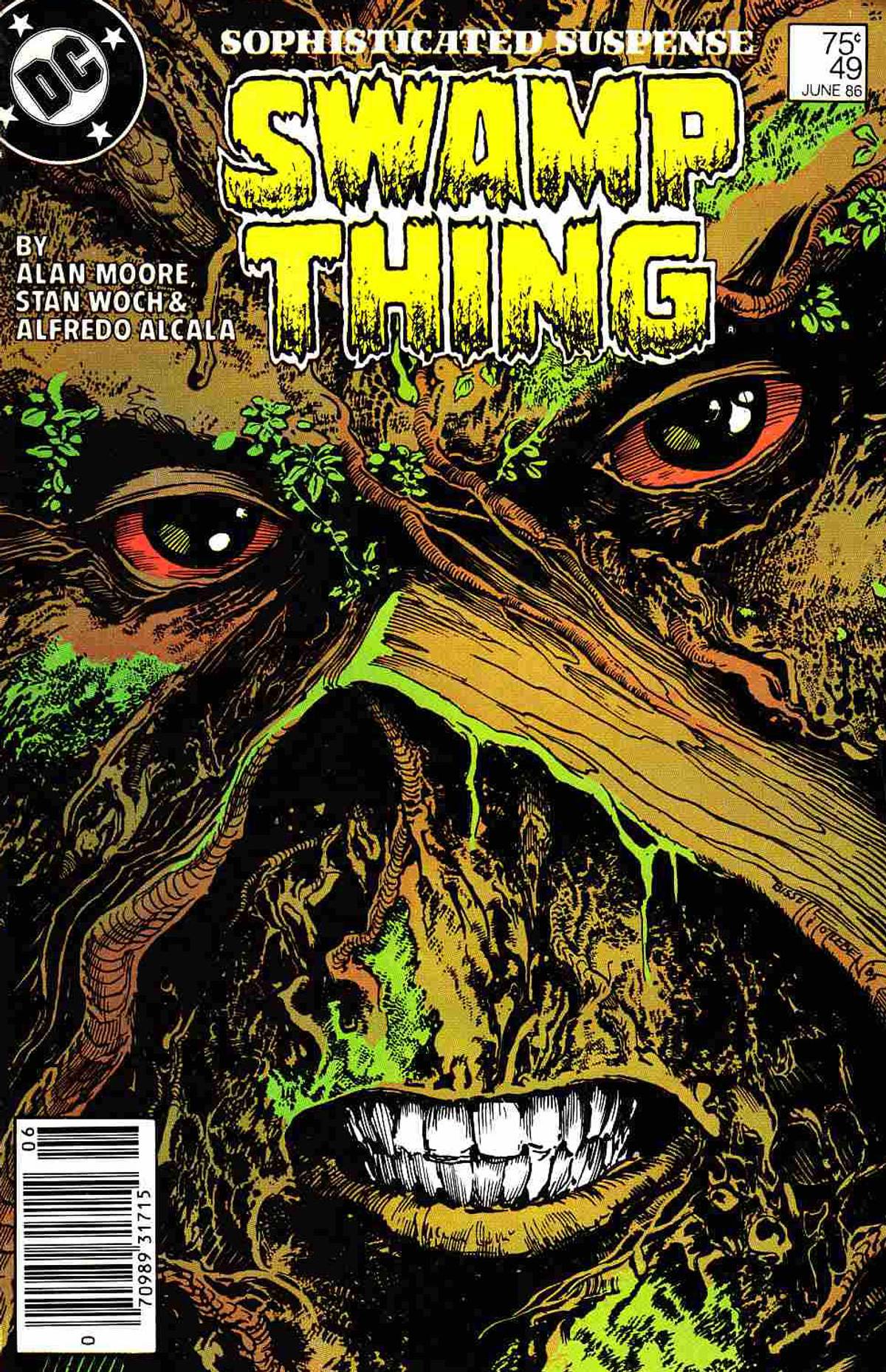

Of the three members of the Swamp Monster Class of 1971, the class valedictorian and Most Likely to Succeed turned out to be Swamp Thing. His original series lasted 24 issues, with Gerry Conway taking over scripting duties for most of the latter issues; publication ended in September 1976. The company gave Swamp Thing a second shot with a new series, The Saga of the Swamp Thing, beginning in May 1982. This second series appeared to be sputtering toward the same cancellation its predecessor had suffered when a new writer was brought on board to shake things up. And shake things up Alan Moore did! Beginning with issue No. 20 and continuing for 45 more (or Moore), the young Brit, fresh off writing a classic run of Captain Britain for Marvel UK (for which Sol Brodsky was production manager, remember), completely revamped Swamp Thing’s origin, revealing he is “a plant that dreams it was once a man” and promoting him to the avatar of the mystical Parliament of Trees. Swamp Thing’s popularity with a more mature audience led to DC establishing a new imprint, Vertigo, aimed at adult consumers of literate, explicit horror and fantasy. The character has benefited from a succession of prominent writers after Alan Moore’s run, and his series, although rebooted with new No. 1 issues several times, has remained in print more years than not. Swamp Thing has also shambled into other media, starring in two feature films, Swamp Thing (1982) and The Return of Swamp Thing (1989), as well as two television series, the first of which ran for three seasons on the USA Network from 1990-93 and the second that ran for one season in 2019 on DC Universe.

Although he wasn’t able to pull it off in that slime encrusted year of 1971, Roy Thomas did manage to close the swamp creature circle the following year. He worked on a project for which he had long advocated—a comics adaptation of Theodore Sturgeon’s story “It,” which appeared in issue No. 1 of Marvel’s Supernatural Thrillers, cover dated December 1972. So Sturgeon’s creation, older brother of the original Heap and uncle of the Skywald Heap, the Man-Thing, and Swamp Thing—the distant descendant of the Golem and the patriarch of all swamp monsters—finally got his own comic book.

Shlaap. Schglorp ...

Andrew Fox is the author of, among other titles, Fat White Vampire Blues.